GARDE PERFORMANCES of the 1960S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, wfiMe others may be from any type of computer printer. Tfie quality of this reproducthm Is dependent upon ttie quality of the copy subm itted. Broken or indistinct print, ootored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleodthrough. substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these wiU be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to t>e removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at ttie upper left-tiand comer and continuing from left to rigtit in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have t>een reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higtier qualify 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any pfiotographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional ctiarge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMT CHILDREN'S DANCE: AN EXPLORATION THROUGH THE TECHNIQUES OF MERGE CUNNINGHAM DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sharon L. Unrau, M.A., CM.A. The Ohio State University 2000 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Emeritus Philip Clark Professor Seymour Kleinman, Advisor Assistant Professor Fiona Travis UMI Number 9962456 Copyright 2000 by Unrau, Sharon Lynn All rights reserved. -

Night of 100 Solos: a Centennial Event

2019 Winter/Spring Season Brooklyn Academy of Music Adam E. Max, Katy Clark, BAM Board Chair President William I. Campbell and Nora Ann Wallace David Binder, BAM Board Vice Chairs Artistic Director Night of 100 Solos: A Centennial Event Choreography by Merce Cunningham BAM Howard Gilman Opera House Apr 16 at 7:30pm Running time: approx. 90 minutes, no intermission Presented without inter- Stager Patricia Lent mission, Events consist of Associate stager Jean Freebury excerpts of dances from the Music director John King repertory and new sequences Set designer Pat Steir arranged for the particular performance and place, Costume designers and builders Reid Bartelme & Harriet Jung with the possibility of several Lighting designer Christine Schallenberg separate activities happening Technical director Davison Scandrett at the same time. —Merce Cunningham Co-produced by Brooklyn Academy of Music, the Barbican London, UCLA’s Center for the Art of Performance, and the Merce Cunningham Trust Night of 100 Solos: A Centennial Event is part of the Merce Cunningham Centennial. Night of 100 Solos: A Centennial Event is generously supported by a major grant from the Howard Gilman Foundation. 2019 Winter/Spring is programmed by Joseph V. Melillo. Season Sponsor: Leadership support for dance at BAM provided by The Harkness Foundation for Dance Major support for dance at BAM provided by The SHS Foundation Support for the Signature Artists Series provided by the Howard Gilman Foundation Night of 100 Solos DANCERS Kyle Abraham, Christian Allen, Mariah Anton -

Against Expression?: Avant-Garde Aesthetics in Satie's" Parade"

Against Expression?: Avant-garde Aesthetics in Satie’s Parade A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2020 By Carissa Pitkin Cox 1705 Manchester Street Richland, WA 99352 [email protected] B.A. Whitman College, 2005 M.M. The Boston Conservatory, 2007 Committee Chair: Dr. Jonathan Kregor, Ph.D. Abstract The 1918 ballet, Parade, and its music by Erik Satie is a fascinating, and historically significant example of the avant-garde, yet it has not received full attention in the field of musicology. This thesis will provide a study of Parade and the avant-garde, and specifically discuss the ways in which the avant-garde creates a dialectic between the expressiveness of the artwork and the listener’s emotional response. Because it explores the traditional boundaries of art, the avant-garde often resides outside the normal vein of aesthetic theoretical inquiry. However, expression theories can be effectively used to elucidate the aesthetics at play in Parade as well as the implications for expressability present in this avant-garde work. The expression theory of Jenefer Robinson allows for the distinction between expression and evocation (emotions evoked in the listener), and between the composer’s aesthetical goal and the listener’s reaction to an artwork. This has an ideal application in avant-garde works, because it is here that these two categories manifest themselves as so grossly disparate. -

American Masters 200 List Finaljan2014

Premiere Date # American Masters Program Title (Month-YY) Subject Name 1 ARTHUR MILLER: PRIVATE CONVERSATIONS On the Set of "Death of a Salesman" June-86 Arthur Miller 2 PHILIP JOHNSON: A SELF PORTRAIT June-86 Philip Johnson 3 KATHERINE ANNE PORTER: THE EYE OF MEMORY July-86 Katherine Anne Porter 4 UNKNOWN CHAPLIN (Part 1) July-86 Charlie Chaplin 5 UNKNOWN CHAPLIN (Part 2) July-86 Charlie Chaplin 6 UNKNOWN CHAPLIN (Part 3) July-86 Charlie Chaplin 7 BILLIE HOLIDAY: THE LONG NIGHT OF LADY DAY August-86 Billie Holiday 8 JAMES LEVINE: THE LIFE IN MUSIC August-86 James Levine 9 AARON COPLAND: A SELF PORTRAIT August-86 Aaron Copland 10 THOMAS EAKINS: A MOTION PORTRAIT August-86 Thomas Eakins 11 GEORGIA O'KEEFFE September-86 Georgia O'Keeffe 12 EUGENE O'NEILL: A GLORY OF GHOSTS September-86 Eugene O'Neill 13 ISAAC IN AMERICA: A JOURNEY WITH ISAAC BASHEVIS SINGER July-87 Isaac Bashevis Singer 14 DIRECTED BY WILLIAM WYLER July-87 William Wyler 15 ARTHUR RUBENSTEIN: RUBENSTEIN REMEMBERED July-87 Arthur Rubinstein 16 ALWIN NIKOLAIS AND MURRAY LOUIS: NIK AND MURRAY July-87 Alwin Nikolais/Murray Louis 17 GEORGE GERSHWIN REMEMBERED August-87 George Gershwin 18 MAURICE SENDAK: MON CHER PAPA August-87 Maurice Sendak 19 THE NEGRO ENSEMBLE COMPANY September-87 Negro Ensemble Co. 20 UNANSWERED PRAYERS: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF TRUMAN CAPOTE September-87 Truman Capote 21 THE TEN YEAR LUNCH: THE WIT AND LEGEND OF THE ALGONQUIN ROUND TABLE September-87 Algonquin Round Table 22 BUSTER KEATON: A HARD ACT TO FOLLOW (Part 1) November-87 Buster Keaton 23 BUSTER KEATON: -

Todd Bolender and Janet Reed Were Dancing in Pied Piper When It Hap- Pened, One of Those Unforeseen Stage Mishaps That Can Wreck a Performance Completely

1 Todd Bolender and Janet Reed were dancing in Pied Piper when it hap- pened, one of those unforeseen stage mishaps that can wreck a performance completely. Set to Aaron Copland’s jazzy Concerto for Clarinet and String Orchestra, Pied Piper was Jerome Robbins’s fourth work for New York City Ballet. Its vocabulary was in the same vein as Fancy Free and Interplay, a blend of classical steps, modern dance, and social dancing. For the finale, he included a jitterbug move, in which Bolender had to swing Reed over his head and around his neck, her legs in a wide second position, and from there to the floor directly in front of him. In the early 1950s, when this per- formance took place, Bolender had begun wearing a wig over his thinning hair that fit over his scalp like a hat. At this particular performance, all was going well, until Bolender, after swinging Reed down to the floor, looked down and thought, “My God, has she lost her tights” at the same moment that Reed looked in the same direction. They both broke into uncontrol- lable laughter, fortunately just as the corps came rushing onto the stage and covered their hasty exit, Bolender’s much-loathed wig (“it had curls and things,” he told Deborah Jowitt) restored to his head.1 By 1952, when it’s likely this performance took place,2 Bolender and Reed had been friends since Reed arrived in New York in January 1942. They had been dancing together in Robbins’s and Balanchine’s work since 1949, when Reed joined City Ballet. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions Of

June 7, 2006 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E1039 IN RECOGNITION OF THE WOMEN’S H. Savage of Idaho, David Williams Simnick of She will forever remain an inspiration to DIVISION OF THE FORT WORTH Illinois, Martin Iran Turman, Jr. of Indiana, many who seek guidance in her wisdom and METROPOLITAN BLACK CHAM- Preston Scott Bates of Kentucky, Seth D. words. She was noted for her no nonsense BER OF COMMERCE Dixon also of Kentucky, Benjamin David approach to the way of life as stated here, Goodman of Maine, Jonathan M. Brookstone ‘‘Don’t be nervous, don’t be tired and above HON. MICHAEL C. BURGESS of Maryland, Zachary Ryan Davis of Massa- all, don’t be bored. Those are the three de- OF TEXAS chusetts, Lauren Brenda Gabriell Hollier of stroyers of freedom’’. Her insight goes far be- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Michigan, Marvin Anthony Liddell also of yond dance and choreography, but into the Michigan, Christine C. DiLisio of Missouri, real human dilemma. It was stated that, ‘‘she Wednesday, June 7, 2006 Vernon Telford Smith IV of Montana, Victoria was speaking less about dance and more Mr. BURGESS. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to Elizabeth Gilbert of the Model United Nations about an area of equal concern: human recognize the contributions of the Women’s program, Eoghan Emmet Kelley of New rights’’. All those who knew her dignified heart Division of the Fort Worth Metropolitan Black Hampshire, Danielle C. Desaulniers of New of compassion could not help but follow her Chamber of Commerce in its support for the Jersey, Juan Carlo Sanchez of New Mexico, lead. -

Atheneum Nantucket Dance Festival

NANTUCKET ATHENEUM DANCE FESTIVAL 2011 Featuring stars of New York City Ballet & Paris Opera Ballet Benjamin Millepied Artistic Director Dorothée Gilbert Teresa Reichlen Amar Ramasar Sterling Hyltin Tyler Angle Daniel Ulbricht Maria Kowroski Alessio Carbone Ana Sofia Scheller Sean Suozzi Chase Finlay Georgina Pazcoguin Ashley Laracey Justin Peck Troy Schumacher Musicians Cenovia Cummins Katy Luo Gillian Gallagher Naho Tsutsui Parrini Maria Bella Jeffers Brooke Quiggins Saulnier Cover: Photo of Benjamin Millepied by Paul Kolnik 1 Welcometo the Nantucket Atheneum Dance Festival! For 177 years the Nantucket Atheneum has enriched our island community through top quality library services and programs. This year the library served more than 200,000 adults, teens and children year round with free access to over 1.4 million books, CDs, and DVDs, reference and information services and a wide range of cultural and educational programs. In keeping with its long-standing tradition of educational and cultural programming, the Nantucket Atheneum is very excited to present a multifaceted dance experience on Nantucket for the fourth straight summer. This year’s performances feature the world’s best dancers from New York City Ballet and Paris Opera Ballet under the brilliant artistic direction of Benjamin Millepied. In addition to live music for two of the pieces in the program, this year’s program includes an exciting world premier by Justin Peck of the New York City Ballet. The festival this week has offered a sparkling array of free community events including two dance-related book author/illustrator talks, Frederick Wiseman’s film La Danse, Children’s Workshop, Lecture Demonstration and two youth master dance classes. -

News from the Jerome Robbins Foundation Vol

NEWS FROM THE JEROME ROBBINS FOUNDATION VOL. 6, NO. 1 (2019) The Jerome Robbins Dance Division: 75 Years of Innovation and Advocacy for Dance by Arlene Yu, Collections Manager, Jerome Robbins Dance Division Scenario for Salvatore Taglioni's Atlanta ed Ippomene in Balli di Salvatore Taglioni, 1814–65. Isadora Duncan, 1915–18. Photo by Arnold Genthe. Black Fiddler: Prejudice and the Negro, aired on ABC-TV on August 7, 1969. New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, “backstage.” With this issue, we celebrate the 75th anniversary of the Jerome Robbins History Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. In 1944, an enterprising young librarian at The New York Public Library named One of New York City’s great cultural treasures, it is the largest and Genevieve Oswald was asked to manage a small collection of dance materials most diverse dance archive in the world. It offers the public free access in the Music Division. By 1947, her title had officially changed to Curator and the to dance history through its letters, manuscripts, books, periodicals, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, known simply as the Dance Collection for many prints, photographs, videos, films, oral history recordings, programs and years, has since grown to include tens of thousands of books; tens of thousands clippings. It offers a wide variety of programs and exhibitions through- of reels of moving image materials, original performance documentations, audio, out the year. Additionally, through its Dance Education Coordinator, it and oral histories; hundreds of thousands of loose photographs and negatives; reaches many in public and private schools and the branch libraries. -

![JOHN CAGE: SIXTEEN DANCES SIXTEEN DANCES (1951) JOHN CAGE 1912–1992 [1] No](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0131/john-cage-sixteen-dances-sixteen-dances-1951-john-cage-1912-1992-1-no-1540131.webp)

JOHN CAGE: SIXTEEN DANCES SIXTEEN DANCES (1951) JOHN CAGE 1912–1992 [1] No

JOHN CAGE: SIXTEEN DANCES SIXTEEN DANCES (1951) JOHN CAGE 1912–1992 [1] No. 1 [Anger] 1:27 SIXTEEN DANCES [2] No. 2 [Interlude] 3:07 [3] No. 3 [Humor] 1:43 [4] No. 4 [Interlude] 2:06 BOSTON MODERN ORCHESTRA PROJECT [5] No. 5 [Sorrow] 2:01 GIL ROSE, CONDUCTOR [6] No. 6 [Interlude] 2:17 [7] No. 7 [The Heroic] 2:40 [8] No. 8 [Interlude] 3:29 [9] No. 9 [The Odious] 3:10 [10] No. 10 [Interlude] 2:20 [11] No. 11 [The Wondrous] 2:05 [12] No. 12 [Interlude] 2:09 [13] No. 13 [Fear] 1:24 [14] No. 14 [Interlude] 5:12 [15] No. 15 [The Erotic] 3:10 [16] No. 16 [Tranquility] 3:51 TOTAL 42:12 COMMENT By David Vaughan At the beginning of the 1950’s, John Cage began to use chance operations in his musical composition. He and Merce Cunningham were working on a big new piece, Sixteen Dances for Soloist and Company of Three. To facilitate the composition, Cage drew up a series of large charts on which he could plot rhythmic structures. In working with these charts, he caught first glimpse of a whole new approach to musical composition—an approach that led him very quickly to the use of chance. “Somehow,” he said, “I reached the conclusion that I could compose according to moves on these charts instead of according to my own taste.”1 The composer Christian Wolff introduced Cage to theI Ching, or Book of Changes, which COMPANY CUNNINGHAM DANCE OF MERCE COURTESY PETERICH, GERDA PHOTO: (1951). -

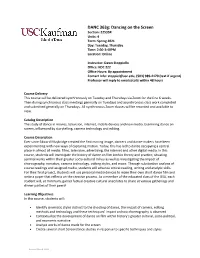

DANC 363G Syllabus S21

DANC 363g: Dancing on the Screen Section: 22535R Units: 4 Term: Spring 2021 Day: Tuesday, Thursday Time: 2:00-3:40PM Location: Online Instructor: Dawn Stoppiello Office: KDC 222 Office Hours: By appointment Contact Info: [email protected], (503) 989-4170 (text if urgent) Professor will reply to emails/calls within 48 hours Course Delivery This course will be delivered synchronously on Tuesday and Thursdays via Zoom for the first 6 weeks. Then during synchronous class meetings generally on Tuesdays and asynchronous class work completed and submitted generally on Thursdays. All synchronous Zoom classes will be recorded and available to view. Catalog Description The study of dance in movies, television, internet, mobile devices and new media. Examining dance on screen, influenced by storytelling, camera technology and editing. Course Description Ever since Edward Muybridge created the first moving image, dancers and dance-makers have been experimenting with new ways of capturing motion. Today, this has led to dance occupying a central place in almost all media: films, television, advertising, the internet and other digital media. In this course, students will investigate the history of dance on film both in theory and practice, situating seminal works within their greater socio-cultural milieu as well as investigating the impact of choreography, narrative, camera technology, editing styles, and music. Through substantive analysis of course readings and assigned media, students will advance critical reading, writing and analytic skills. For their final project, students will use personal media devices to make their own short dance film and write a paper that reflects on the creative process. -

Transcription of Text on Panel B of Robert Rauschenberg's Autobiography (1968)

SFMOMA Rauschenberg Research Project: Curatorial Document Transcription of text on panel B of Robert Rauschenberg’s Autobiography (1968). SFMOMA Permanent Collection Object Files Port Arthur Texas Oct. 22, 1925. Mother: Dora. Father: Ernest (grandparents): Holland Dutch, Swedish, German, Cherokee. De Queen Gr. Sch., Woodrow Wilson H. Sch. Jr., Thomas Jefferson H. Sch. Grad. 1942. / U. of Tex. U.S. Navy 2 ½ yrs neuropsychiatric tech. Family moved to Lafayette La. with sister, Janet, born Apr. 23, 1936. After Navy: / returned home, left home. Worked in Los Angeles. Moved to Kansas City to study painting K.C.A.I. went to Paris, 1947, met Sue Weil. Std. Acad. Julian. 1948 Black Mountain College N.C. disciplined by Albers. Learned photography. Worked hard but poorly for Albers. Made contact with music and modern dance. Felt too isolated, Sue and I moved to NYC. Went to Art Students League. Vytlacil & Kantor. Best work made at home. Wht. Painting with no.’s best example. Summer 1950, Outer Island Conn. Married Sue Weil. Christopher (son) born July 16, 1951 in NYC. First one man show Betty Parsons: paintings mostly silver & wht. with cinematic composition. All paintings destroyed in two accidental fires. Summer Blk. Mt. Coll. N.C. started all blk. & all wht. paintings. Winter divorced. Sue & Christopher living in NYC. I went to Italy with painter & friend Cy Twombly. Ran out of money in Rome. Took chance getting job in Casablanca at Atlas Construction Co. Worked 2 mo. Got sick, left. Traveled Fr. & Sp. Morocco. Returned to Rome. While traveling constructed rope objects & boxes. Showed in Rome & Florence. -

Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) Announces 2018 Next Wave

Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) announces 2018 Next Wave Festival, featuring 27 music, opera, theater, physical theater, dance, film/music, and performance art engagements, Oct 3—Dec 23 Bloomberg Philanthropies is the Season Sponsor Music/Opera Almadraba…………………… Oscar Peñas…………………………..…………………..page 3 Place…………………………. Ted Hearne, Saul Williams, Patricia McGregor………. page 6 The Ecstatic Music of Alice Coltrane …………………………..…………………………page 6 Satyagraha…………………...Philip Glass, Tilde Björfors, Folkoperan, Cirkus Cirkör..page 17 Savage Winter…………...….. Douglas J. Cuomo, Jonathan Moore, American Opera Projects, Pittsburgh Opera……………………………… page 19 Circus: Wandering City…….. ETHEL……………………………………………………. page 22 Greek………………………… Scottish Opera/Opera Ventures, Mark-Anthony Turnage, Joe Hill-Gibbins, Jonathan Moore, Stuart Stratford….. page 28 Theater The Bacchae…………………SITI Company, Anne Bogart, Aaron Poochigian…….. .page 4 Measure for Measure………. Cheek by Jowl, Pushkin Drama Theatre, Declan Donnellan, Nick Ormerod……………………….page 9 Jack &................................... Kaneza Schaal, Cornell Alston………………………… .page 10 Falling Out…………………… Phantom Limb Company……………………………….. .page 20 The Good Swimmer…………Heidi Rodewald, Donna Di Novelli, Kevin Newbury…. .page 25 The White Album…………….Early Morning Opera, Lars Jan, Joan Didion………… .page 26 NERVOUS/SYSTEM………..Andrew Schneider………………………………………...page 32 Strange Window: The Turn of the Screw…………………. The Builders Association, Marianne Weems…………..page 33 Physical theater Humans……………………… Circa, Yaron Lifschitz……………………………………..page