A Simplified Guide to Explosives Analysis Introduction a Backpack Left on a Crowded City Street

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Development of a Correlation Between

DEVELOPMENT OF A CORRELATION BETWEEN ROTARY DRILL PERFORMANCE AND CONTROLLED BLASTING POWDER FACTORS by JOHN CHARLES LEIGHTON B.A.Sc, The University of British Columbia, 1978 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF APPLIED SCIENCE in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Mining and Mineral Process Engineering We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA August 1982 © John Charles Leighton, 1982 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. John Charles Leighton Department of MIVMVI3 The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date DE-6 (.3/81) - i i - ABSTRACT Despite the availability of established, sophisticated methods for plan• ning and designing stable slopes in rock, comparatively little attention is usually paid to the problems of carrying out the excavation. Blasting should be carefully planned to obtain optimum fragmentation as well as steep, stable pit walls for a minimum stripping ratio. The principal difficulty facing a blast designer is the lack of prior information about the many critical blasting characteristics of the rock mass. -

Guide for the Selection of Commercial Explosives Detection Systems for Law Enforcement Applications

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs National Institute of Justice National Institute of Justice ABOUT THELaw LAW Enforcement ENFORCEMENT and Corrections AND CORRECTIONS Standards and Testing Program Guide for the Selection of Commercial Explosives Detection Systems for Law Enforcement Applications NIJ Guide 100-99 U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs 810 Seventh Street N.W. Washington, DC 20531 Janet Reno Attorney General Raymond C. Fisher Associate Attorney General Laurie Robinson Assistant Attorney General Noël Brennan Deputy Assistant Attorney General Jeremy Travis Director, National Institute of Justice Office of Justice Programs National Institute of Justice World Wide Web Site World Wide Web Site http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/nij ABOUT THE LAW ENFORCEMENT AND CORRECTIONS STANDARDS AND TESTING PROGRAM The Law Enforcement and Corrections Standards and Testing Program is sponsored by the Office of Science and Technology of the National Institute of Justice (NIJ), U.S. Department of Justice. The program responds to the mandate of the Justice System Improvement Act of 1979, which created NIJ and directed it to encourage research and development to improve the criminal justice system and to disseminate the results to Federal, State, and local agencies. The Law Enforcement and Corrections Standards and Testing Program is an applied research effort that determines the technological needs of justice system agencies, sets minimum performance standards for specific devices, tests commercially available equipment against those standards, and disseminates the standards and the test results to criminal justice agencies nationally and internationally. The program operates through: The Law Enforcement and Corrections Technology Advisory Council (LECTAC) consisting of nationally recognized criminal justice practitioners from Federal, State, and local agencies, which assesses technological needs and sets priorities for research programs and items to be evaluated and tested. -

Explosive Weapon Effectsweapon Overview Effects

CHARACTERISATION OF EXPLOSIVE WEAPONS EXPLOSIVEEXPLOSIVE WEAPON EFFECTSWEAPON OVERVIEW EFFECTS FINAL REPORT ABOUT THE GICHD AND THE PROJECT The Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) is an expert organisation working to reduce the impact of mines, cluster munitions and other explosive hazards, in close partnership with states, the UN and other human security actors. Based at the Maison de la paix in Geneva, the GICHD employs around 55 staff from over 15 countries with unique expertise and knowledge. Our work is made possible by core contributions, project funding and in-kind support from more than 20 governments and organisations. Motivated by its strategic goal to improve human security and equipped with subject expertise in explosive hazards, the GICHD launched a research project to characterise explosive weapons. The GICHD perceives the debate on explosive weapons in populated areas (EWIPA) as an important humanitarian issue. The aim of this research into explosive weapons characteristics and their immediate, destructive effects on humans and structures, is to help inform the ongoing discussions on EWIPA, intended to reduce harm to civilians. The intention of the research is not to discuss the moral, political or legal implications of using explosive weapon systems in populated areas, but to examine their characteristics, effects and use from a technical perspective. The research project started in January 2015 and was guided and advised by a group of 18 international experts dealing with weapons-related research and practitioners who address the implications of explosive weapons in the humanitarian, policy, advocacy and legal fields. This report and its annexes integrate the research efforts of the characterisation of explosive weapons (CEW) project in 2015-2016 and make reference to key information sources in this domain. -

Fire Restrictions

United States Department of the Interior BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT Color Country District 176 East DL Sargent Drive Cedar City, UT 84721 https://www.blm.gov/utah FIRE PREVENTION ORDER: UT-020-21-01 Pursuant to regulations of the Department of the Interior, found at Title 43 CFR 9212.1 (h), the additional following acts are prohibited on Bureau of Land Management (BLM) lands, roads, waterways, and trails, in the State of Utah, until rescinded by the Color Country District Manager. Area Description: All BLM administered public lands within the Color Country District in Washington, Iron, Beaver, Kane, and Garfield counties, Utah. This order is effective at 00:01 a.m. on Wednesday, May 26, 2021 and will remain in effect until rescinded. This order also rescinds all previous orders covering BLM administered public lands in those counties. Prohibited Acts: 1. No campfires using charcoal, solid fuels, or any ash-producing fuel, except in permanently constructed cement or metal fire pits located in agency developed campgrounds and picnic areas. Examples of solid fuels include, but are not limited to wood, charcoal, peat, coal, Hexamine fuel tablets, wood pellets, corn, wheat, rye, and other grains. Devices fueled by petroleum or liquid petroleum gas with a shut-off valve are approved in all locations if there is at least three feet in diameter that is barren with no flammable vegetation. 2. Smoking except within an enclosed vehicle, covered areas, developed recreation site or while stopped in a cleared area of at least three feet in diameter that is barren with no flammable vegetation. -

Sunnyside 59 SGC-073806 Colorado

MINE SAFETY & TRAINING PROGRAM OPERATOR’S ANNUAL REPORT REPORT YEAR 1995 Mins Num ber: ¿ P i____________ Location: Section 21 Township_42j_Range_7M. Mine Name: Sunnyside Mine_________________________ Countv San Juan-------- ANNUAL ACTIVITY Idle X Reclamation X Rehabilitation________ Exploration_________ Development_________ _ Production---------- Crude Tonnage: Tons______ __________________ Yards. Drivage Footage: Shafts____________________„ ( f t ) Raise— -------------------------------------(ft) Drifts/Entries _ _ ___________ ____________ — ------------ ------------------^ Map Submitted (Y/N) Y______ Year's Estimated Reserves ,,_,N/A----------------------------- PRODUCTION FOR THE YEAR Current Year: Amount Value Current Year: Amount Value Coal (tons)___________ $____________ Gold (ozs) ------------------- $-------------------- Gem Stones (lbs) __________ $____________ Lead (ibs) ------------------ $ ------------------- . Silver (ozs) ___________ $____________ Molybdenum (lbs) ------------------ $-------------------- Zinc (lbs) ___________ $ ___________ _ Cadmium (ibs) -------------------- $-------------------- Uranium (ibs) ___________ $ ____________ Vanadium (Ibs) -------------------- $-------------------- Oil-.Shale . (bri). :__________ $ - Copper (ibs) ------------- -------- $_------------ ------ Tungsten (lbs) __________ $____________ Tourist (ea.) -------;— $ ------------------------ Rock (tons)__________ $____________ Misc. Metals ------------------ $-------------------- EMPLOYMENT STATISTICS Average Employment: Underground Mine -

TWGFEX Suggested Guide for Explosive Analysis Training

Suggested Guide for Explosive Analysis Training This is a suggested guideline for the training of an examiner in the field of explosive analysis by an appropriately qualified explosives examiner/analyst. If an appropriate instructor is unavailable, the corresponding sections of the training should be sought externally. This training guide may be modified to fit an agency’s training requirements and goals. All training must be conducted following proper safety procedures as prescribed by the appropriate agency/organization guidelines, as well as all applicable laws/regulations. When practical and available, coordination with local bomb squads is highly recommended. All training must include proper documentation upon completion of each section/module. The trainee may not have to complete all sections. The needs and available instrumentation of the agency will dictate the individual training program selected from the following guidelines. However, the trainee needs to be aware of other analytical methods that are utilized elsewhere. Methods of instruction may include instructions by trainer, self study and/or online guides and/or external instruction. Method of evaluation may include oral, written and/or practical exercise(s). Suggested readings may be found for each section in the accompanying bibliography. I. Introduction Introduction to Explosives Objectives: Upon completion of this unit the student will be able to: 1. Describe the historical development of explosives. (i.e. black powder, TNT, smokeless powder, nitroglycerin, pyrotechnics, etc.) 2. Describe the different types of explosives and how they can be classified. Examples of the different classification systems should include: low vs. high, deflagrating vs. detonating, DOT shipping classifications, chemical classifications, etc. -

United States Department of the Interior

United States Department of the Interior BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT Paria River District 669 South Highway 89A Kanab, UT 84741 https://www.blm.gov/utah FIRE PREVENTION ORDER: UT-020-20-01 Pursuant to regulations of the Department of Interior, found at Title 43 CFR 9212.1 (h), the additional following acts are prohibited on Bureau of Land Management (BLM) lands, roads, waterways, and trails, in the State of Utah, until rescinded by the Paria River District Manager. Area Description: All BLM administered public lands in Kane and Garfield County, Utah. This order is effective at 00:01 a.m. on Friday, June 26, 2020 and will remain in effect until rescinded. Prohibited Acts: 1. No campfires, except in permanently constructed cement or metal fire pits provided in agency developed campgrounds and picnic areas. 2. Grinding, cutting, and welding of metal. 3. Operating or using any internal or external combustion engine without a spark arresting device properly installed, maintained and in effective working order as determined by the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) recommended practices J335 and J350. Refer to Title 43 CFR 8343.1. 4. Possession and/or detonation of explosives, including exploding targets as defined by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives in 27 CFR 555. 5. Fireworks and Incendiary or chemical devices, and pyrotechnics as defined in 49 CFR 173. Binary Explosive Definition: Binary explosive- includes, but is not limited to, pre-packaged products consisting of two separate components, usually an oxidizer like ammonium nitrate and a fuel such as aluminum or another metal. These binary explosives are defined by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosive in 27 CFR 555. -

Guide for the Selection of Commercial Explosives Detection Systems For

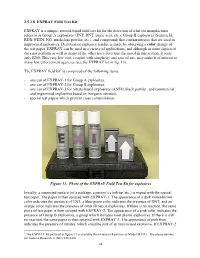

2.5.3.8 EXPRAY Field Test Kit EXPRAY is a unique, aerosol-based field test kit for the detection of what the manufacturer refers to as Group A explosives (TNT, DNT, picric acid, etc.), Group B explosives (Semtex H, RDX, PETN, NG, smokeless powder, etc.), and compounds that contain nitrates that are used in improvised explosives. Detection of explosive residue is made by observing a color change of the test paper. EXPRAY can be used in a variety of applications, and although in some aspects it does not perform as well as many of the other trace detectors discussed in this section, it costs only $250. This very low cost, coupled with simplicity and ease of use, may make it of interest to many law enforcement agencies (see the EXPRAY kit in fig. 13). The EXPRAY field kit2 is comprised of the following items: - one can of EXPRAY-1 for Group A explosives, - one can of EXPRAY-2 for Group B explosives, - one can of EXPRAY-3 for nitrate-based explosives (ANFO, black powder, and commercial and improvised explosives based on inorganic nitrates), - special test papers which prevent cross contamination. Figure 13. Photo of the EXPRAY Field Test Kit for explosives Initially, a suspected surface (of a package, a person’s clothing, etc.) is wiped with the special test paper. The paper is then sprayed with EXPRAY-1. The appearance of a dark violet-brown color indicates the presence of TNT, a blue-green color indicates the presence of DNT, and an orange color indicates the presence of other Group A explosives. -

TWGFEX Glossary of Terms

Glossary of terms ANFO A mixture of ammonium nitrate and fuel oil. Base Charge The main high explosive charge in a blasting cap. Binary Explosive Two substances which are not explosive until they are mixed. Black Powder A low explosive traditionally consisting of potassium nitrate, sulfur and charcoal. Sodium nitrate may be found in place of potassium nitrate. Black Powder Substitutes Modified black powder formulations such as but not limited to: Pyrodex, Black Canyon, Golden Powder, Clean Shot, and Clear Shot. Blasting Agent A high explosive with low-sensitivity usually based on ammonium nitrate and not containing additional high explosive(s). Blasting Cap A metal tube containing a primary high explosive capable of initiating most explosives. Bomb A device containing an explosive, incendiary, or chemical material designed to explode. Booby Trap A concealed or camouflaged device designed to injure or kill personnel. Booster A cap sensitive high explosive used to initiate other less sensitive high explosives. Brisance The shattering power associated with high explosives. C4 A white pliable military plastic explosive containing primarily Cyclonite (RDX). Cannon Fuse A coated, thread-wrapped cord filled with black powder designed to initiate flame-sensitive explosives. Combustion Any type of exothermic oxidation reaction, including, but not limited to burning, deflagration and/or detonation. Deflagration An exothermic reaction that occurs particle to particle at subsonic speed. Detasheet (Det Sheet) A plastic explosive in sheet form containing PETN, HMX or RDX. Detonation An exothermic reaction that propagates a shockwave through an explosive at supersonic speed (greater than 3300ft/sec). Detonation Cord (Det-Cord) A plastic/fiber wrapped cord containing a core of PETN or RDX. -

Engineering Geology Field Manual

Chapter 19 BLAST DESIGN Introduction This chapter is an introduction to blasting techniques based primarily on the Explosives and Blasting Procedures Manual (Dick et al., 1987) and the Blaster’s Handbook (E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co., Inc., 1978). Blast design is not a precise science. Because of widely varying properties of rock, geologic structure, and explo- sives, design of a blasting program requires field testing. Tradeoffs frequently must be made when designing the best blast for a given geologic situation. This chapter provides the fundamental concepts of blast design. These concepts are useful as a first approximation for blast design and also in troubleshooting the cause of a bad blast. Field testing is the best tool to refine individual blast designs. Throughout the blast design process, two overriding prin- ciples must be kept in mind: (1) Explosives function best when there is a free face approximately parallel to the explosive column at the time of detonation. (2) There must be adequate space for the broken rock to move and expand. Excessive confinement of explosives is the leading cause of poor blasting results such as backbreak, ground vibrations, airblast, unbroken toe, flyrock, and poor fragmentation. Properties and Geology of the Rock Mass The rock mass properties are the single most critical variable affecting the design and results of a blast. The FIELD MANUAL rock properties are very qualitative and cannot be suffi- ciently quantified numerically when applied to blast design. Rock properties often vary greatly from one end of a construction job to another. Explosive selection, blast design, and delay pattern must consider the specific rock mass being blasted. -

ATF EXPLOSIVES Industry Newsletter December 2011 Published Bi-Annually

U.S. Department of Justice Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives ATF EXPLOSIVES Industry Newsletter December 2011 Published Bi-Annually What’s In This Issue New Acting Director of ATF New Acting Director of ATF New Publications Todd Jones, U.S. Attorney for the District Open Letter—Definition of Display Fireworks of Minnesota, has been named the Acting ATF Ruling 2011-3, Alternate Locks Authorized for B. Director of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Explosives Magazines Firearms and Explosives (ATF). Jones received his Juris Nonsparking Metals Doctor from the University of Minnesota Law School in Attended “Day Box” Reminders 1983. Following admission to the Minnesota bar, he went on active duty in the U.S. Marine Corps, where he served Smokeless Powder Exemption as both a trial defense counsel and prosecutor. Binary Exploding Targets Prior to becoming a U.S. Attorney, Jones was a partner Binary Explosives Security with a national law firm in Minneapolis, where his Certain Pest Control Devices Exempted as “Articles practice focused on business litigation. He also has Pyrotechnic” served as special counsel to various boards of directors Hobby Pyrotechnics in a Regulated Environment of public and privately held companies. In that capacity, he has led internal investigations and provided guidance Explosives Licensing and Transfers on compliance and governance issues. During his initial Reporting RPs and EPs tenure as a Federal prosecutor, Jones conducted grand U.S. Geological Survey Mineral Yearbook jury investigations and was the lead trial lawyer in a number of Federal prosecutions involving drug traffick- ing, financial fraud, firearms, and violent crime. -

Bernalillo County PM10 Emission Inventory for 2004

FINAL Bernalillo County PM10 Emission Inventory for 2004 Prepared by David DuBois Ilias Kavouras Prakash Doraiswamy Jin Xu Desert Research Institute Division of Atmospheric Sciences 755 E. Flamingo Rd Las Vegas, NV Prepared for Mr. Fabian Macias Air Quality Division City of Albuquerque 11850 Sunset Gardens Rd, SW Albuquerque, NM 87121 April 27, 2006 1 Acknowledgements This work was funded by the City of Albuquerque’s Air Quality Division in the Environmental Health Department for developing a PM10 emission inventory for point, area and mobile sources for the calendar year of 2004. We appreciate the work of Dr. Brinda Ramanathan for providing research in various sectors as well as taking part in the quality assurance. The authors sincerely thank the following personnel for their help at different stages of this work: Mr. Fabian Macias and Ms Stephanie Summers of the Air Quality Division, Mr. Glen Dennis and Mr. Ron Latimer of the Vehicle Pollution Management Division and Ms. Shohreh Day and Mr. Nathan Masek of Mid Region Council of Governments (MRCOG). 2 Table of Contents List of Tables 6 List of Figures 10 Acronyms 12 1. Introduction.......................................................................................................................15 1.1 Inventory Year...........................................................................................................15 1.2 Geographic Domain...................................................................................................15 1.3 Pollutant.....................................................................................................................15