Lycoming 2030: Plan the Possible 3-113 Countywide Comprehensive Plan Chapter 3: County Priorities 2018 COUNTY COMPREHENSIVE PLAN UPDATE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Class a Wild Trout Streams

CLASS A WILD TROUT STREAMS STATEWIDE WATER QUALITY STANDARDS REVIEW STREAM REDESIGNATION EVALUATION Drainage Lists: A, C, D, E, F, H, I, K, L, N, O, P, Q, T WATER QUALITY MONITORING SECTION (MAB) DIVISION OF WATER QUALITY STANDARDS BUREAU OF POINT AND NON-POINT SOURCE MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION December 2014 INTRODUCTION The Department of Environmental Protection (Department) is required by regulation, 25 Pa. Code section 93.4b(a)(2)(ii), to consider streams for High Quality (HQ) designation when the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission (PFBC) submits information that a stream is a Class A Wild Trout stream based on wild trout biomass. The PFBC surveys for trout biomass using their established protocols (Weber, Green, Miko) and compares the results to the Class A Wild Trout Stream criteria listed in Table 1. The PFBC applies the Class A classification following public notice, review of comments, and approval by their Commissioners. The PFBC then submits the reports to the Department where staff conducts an independent review of the trout biomass data in the fisheries management reports for each stream. All fisheries management reports that support PFBCs final determinations included in this package were reviewed and the streams were found to qualify as HQ streams under 93.4b(a)(2)(ii). There are 50 entries representing 207 stream miles included in the recommendations table. The Department generally followed the PFBC requested stream reach delineations. Adjustments to reaches were made in some instances based on land use, confluence of tributaries, or considerations based on electronic mapping limitations. PUBLIC RESPONSE AND PARTICIPATION SUMMARY The procedure by which the PFBC designates stream segments as Class A requires a public notice process where proposed Class A sections are published in the Pennsylvania Bulletin first as proposed and secondly as final, after a review of comments received during the public comment period and approval by the PFBC Commissioners. -

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5 DATABASE DESIGN DOCUMENTATION AND DATA DICTIONARY 1 June 2013 Prepared for: United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, Maryland 21403 Prepared By: Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 Prepared for United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, MD 21403 By Jacqueline Johnson Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin To receive additional copies of the report please call or write: The Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 301-984-1908 Funds to support the document The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.0; Database Design Documentation And Data Dictionary was supported by the US Environmental Protection Agency Grant CB- CBxxxxxxxxxx-x Disclaimer The opinion expressed are those of the authors and should not be construed as representing the U.S. Government, the US Environmental Protection Agency, the several states or the signatories or Commissioners to the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin: Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia or the District of Columbia. ii The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.5 TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. -

Pennsylvania Nonpoint Source Program Fy2003 Project Summary

Rev.1/30/03 PENNSYLVANIA NONPOINT SOURCE PROGRAM FY2003 PROJECT SUMMARY Base Program/District Staff Project Title: Conservation District Mining Program Project Number: 2301 Budget: $ 125,000 Lead Agency: Western Pennsylvania Coalition for Abandoned Mine Reclamation (WPCAMR) Location: Western Pennsylvania bituminous coal region Point of Contact: Garry Price, BWM or Bruce Golden, Regional Coordinator, Western Pennsylvania Coalition for Abandoned Mine Reclamation The purpose of the WPCAMR is to promote and facilitate the reclamation and remediation of abandoned mine drainage (AMD) in western Pennsylvania. Through this project the Regional Coordinator will continue to develop an education program, coordinate AMD remediation activities, generate local support for remediation efforts, and assist watershed associations and conservation districts in the development of watershed management plans and in securing funding for AMD remediation. The Watershed Coordinator will continue to assist with the development and implementation of funded projects. Project Title: Conservation District Mining Program Project Number: 2302 Budget: $ 118,000 Lead Agency: Eastern Pennsylvania Coalition for Abandoned Mine Reclamation (EPCAMR) Location: Anthracite and northern bituminous regions of Pennsylvania Point of Contact: Garry Price, BWM or Robert Hughes, Eastern Pennsylvania Coalition for Abandoned Mine Reclamation EPCAMR was formed to promote and facilitate the reclamation and remediation of land and water adversely affected by past coal mining practices in eastern Pennsylvania. EPCAMR is a complimentary organization to the Western Pennsylvania Coalition. The EPCAMR Regional Coordinator will continue efforts to organize watershed associations, develop an education program, coordinate AMD remediation activities, generate local support for remediation efforts, and assist watershed associations and conservation districts in the development of watershed management plans and in securing funding for AMD remediation. -

Report Abstract

SL-145-1 REPORT ABSTRACT GENERAL INFORMATION Location and Geographics (p. 2) The Babb Creek Watershed is located in North Central Pennsylvania, occupying the southern portion of Tioga County and a small portion of northern Lycoming County. The area within the watershed is approximately 129 square miles, 65% of which is forested. The remaining 35% is agriculture and rural residential. The primary traffic arteries are Pa. T.R. 287 and U.S. Rt. 15. Topography and Drainage (pp. 3-4) The study area is in the upland plateau section of the Appalachian Physiographic Province. Elevation extremes are from a low of 860 feet above sea level at the confluence of Babb Creek and Pine Creek to more than 2200 feet along the sandstone ridges. Drainage forms a dendrite pattern commonly associated with plateau regions. Drainage into Babb Creek is received from three major tributaries--Lick Creek, Wilson Creek and Stony Fork Creek. Geology and Mining (pp. 5-12) Coal bearing strata in the project area are referable primarily to the Allegheny Group of Pennsylvania age. The coals are found in the Blossburg Syncline which traverses the study area northeastward from Pine Creek to Arnot. Six coals are present, four of which were mined. The major coal horizon is the Bloss vein which is tentatively correlated with Lower Kittanning of standard Pennsylvania Bituminous Coals. History of Deep Mining Activities (pp. 13-15) Coal was discovered at Blossburg in 1792, with the first drift opening" around 1815. The first mines in the Babb Creek Watershed were probably opened in Arnot around 1865. -

Species of Greatest Conservation Need Species Accounts

2 0 1 5 – 2 0 2 5 Species of Greatest Conservation Need Species Accounts Appendix 1.4C-Amphibians Amphibian Species of Greatest Conservation Need Maps: Physiographic Provinces and HUC Watersheds Species Accounts (Click species name below or bookmark to navigate to species account) AMPHIBIANS Eastern Hellbender Northern Ravine Salamander Mountain Chorus Frog Mudpuppy Eastern Mud Salamander Upland Chorus Frog Jefferson Salamander Eastern Spadefoot New Jersey Chorus Frog Blue-spotted Salamander Fowler’s Toad Western Chorus Frog Marbled Salamander Northern Cricket Frog Northern Leopard Frog Green Salamander Cope’s Gray Treefrog Southern Leopard Frog The following Physiographic Province and HUC Watershed maps are presented here for reference with conservation actions identified in the species accounts. Species account authors identified appropriate Physiographic Provinces or HUC Watershed (Level 4, 6, 8, 10, or statewide) for specific conservation actions to address identified threats. HUC watersheds used in this document were developed from the Watershed Boundary Dataset, a joint project of the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture-Natural Resources Conservation Service, the U.S. Geological Survey, and the Environmental Protection Agency. Physiographic Provinces Central Lowlands Appalachian Plateaus New England Ridge and Valley Piedmont Atlantic Coastal Plain Appalachian Plateaus Central Lowlands Piedmont Atlantic Coastal Plain New England Ridge and Valley 675| Appendix 1.4 Amphibians Lake Erie Pennsylvania HUC4 and HUC6 Watersheds Eastern Lake Erie -

A Decade of Progress for the West Branch Susquehanna Restoration

WestA DECADE OF PROGRESS Branch FOR THE Susquehanna Restoration Initiative 2004–2014 A. WOLFE 1 Foreword PA Fish and Boat Commission Executive Director, John Arway In 2012, Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission (PFBC) staff surveyed the upper reaches of the West Branch Susquehanna River in Cambria County and discovered a naturally reproducing wild trout population. The abandoned mine drainage (AMD) remediation efforts, including the Lancashire 15 treatment plant, have improved water quality to PA FISH AND BOAT COMMISSION FISH AND BOAT PA the point where there are now wild trout in the West Branch! With the recently funded Twomile Run project in the lower Kettle Creek watershed and proposed remediation at the abandoned Fran Contracting site in the Cooks Run watershed, there is a great potential to recover significant miles of naturally reproducing brook trout streams in the near future. Another major recent accomplishment is the AMD remediation work that improved water quality in more than forty miles of the Bennett Branch Sinnemahoning Creek. The partnership between government, industry and the public working together on reclamation activities and AMD treatment has allowed PFBC cooperative nurseries to stock a portion of the Bennett Branch in 2013, and the PFBC will be adding a preseason stocking to a 4.5 mile reach in the Medix Run/Benezette area for 2014. Additionally, a 2.8 mile section of the West Branch near Curwensville will receive a preseason trout stocking for the first time in 2014. A. WOLFE These are some exciting times in the West Branch Susquehanna watershed and we look forward to more improvements in the coming years. -

West Branch Subbasin AMD Remediation Strategy

Publication 254 West Branch Susquehanna Subbasin May 2008 AMD Remediation Strategy: West Branch Susquehanna Background, Data Assessment River Task Force and Method Development Despite the enormous legacy ■ INTRODUCTION Pristine setting along the West Branch Susquehanna River. of pollution from abandoned mine The West Branch Susquehanna drainage (AMD) in the West Subbasin, draining a 6,978-square-mile Branch Susquehanna Subbasin, area in northcentral Pennsylvania, is the there has been mounting support largest of the six major subbasins in and enthusiasm for a fully restored the Susquehanna River Basin (Figure 1). watershed. Under the leadership The West Branch Susquehanna of Governor Edward G. Rendell Subbasin is one of extreme contrasts. While and with support from it has some of the Commonwealth’s Trout Unlimited, Pennsylvania most pristine and treasured waterways, Department of Environmental including 1,249 miles of Exceptional Protection Secretary Kathleen Value streams and scenic forestlands and mountains, it also unfortunately M. Smith McGinty established the West bears the legacy of past Branch Susquehanna River Task unregulated mining. With Abandoned mine lands in Clearfield County. Force (Task Force) in 2004. 1,205 miles of waterways The goal of the Task Force is to impaired by AMD, it is the assist and advise the department and most AMD-impaired region its partners as they work toward of the entire Susquehanna the long-term goal to remediate the River Basin (Figure 2). At its most degraded region’s AMD. sites, the West Branch The Task Force is comprised Susquehanna River contains of state, federal, and regional acidity concentrations of agencies, Trout Unlimited, and nearly 200 milligrams per other conservation and watershed liter (mg/l), and iron and aluminum concentrations of organizations (members are identified A. -

May 23, 2015 (Pages 2447-2580)

Pennsylvania Bulletin Volume 45 (2015) Repository 5-23-2015 May 23, 2015 (Pages 2447-2580) Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/pabulletin_2015 Recommended Citation Pennsylvania Legislative Reference Bureau, "May 23, 2015 (Pages 2447-2580)" (2015). Volume 45 (2015). 21. https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/pabulletin_2015/21 This May is brought to you for free and open access by the Pennsylvania Bulletin Repository at Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Volume 45 (2015) by an authorized administrator of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Volume 45 Number 21 Saturday, May 23, 2015 • Harrisburg, PA Pages 2447—2580 Agencies in this issue The Governor The Courts Delaware River Basin Commission Department of Agriculture Department of Banking and Securities Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Department of Drug and Alcohol Programs Department of Environmental Protection Department of General Services Department of Health Department of Transportation Fish and Boat Commission Independent Regulatory Review Commission Insurance Department Liquor Control Board Milk Marketing Board Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission Philadelphia Parking Authority Philadelphia Regional Port Authority Public School Employee’s Retirement Board State Board of Auctioneer Examiners State Board of Nursing State Conservation Commission Thaddeus Stevens College of -

Choosing Watersheds/HUC10 to Perform Modeling on Transport of Contaminants and Possible Detailed Monitoring of Poten�Al Spills Or Background

Choosing Watersheds/HUC10 to perform modeling on transport of contaminants and possible detailed monitoring of potenal spills or background Han, Y., Simon, C., Arjmand, S., Abad, J. D. + ShaleNetwork team Permi=ed Wells Drilled Wells Three Type Violaons 3 Types Violaon: (1) erosion / sedimentaon, (2) polluDon incident, (3) pit & impoundment issues. Permi=ed minus Drilled (P-D) 5% Shortest Time/HUC10 (Han et al, in preparaon) Gauge Staons Stream Use (based on total length of streams) Procedure to obtain crical watersheds • Now, we have the following layers: – 1. Permi=ed wells / HUC10 15% – 2. Drilled wells / HUC10 15% – 3. Three type violaons / HUC10 14% – 4. Permi=ed minus drilled 14% – 5. USGS gauge staons 14% – 6. Stream Use (excepDonal value stream/high quality water…) 14% – 7. 5% shortest Dme / HUC10 14% • Reclassify each layer based on what we concerned, for example, Permi=ed wells reclassified by “count”, Stream use reclassified by “sum_length” • Give a WEIGHT to each layer Weighted Overlay HUC10 Name Permied Drilled 5% 3 Permit Gauge Stream Shortest Violaon Minus Stao Use Time Drilled n South fork Tenmile (South) criDcal criDcal criDcal criDcal criDcal Tioga River criDcal criDcal criDcal criDcal criDcal criDcal Lycomming Creek criDcal criDcal criDcal criDcal criDcal Sugar Creek criDcal criDcal criDcal criDcal criDcal Upper Monogahela River (South) criDcal criDcal criDcal Lower Branch Susquehanna River criDcal Lower Susquehanna River criDcal criDcal criDcal criDcal Tenmile Creek (South) criDcal criDcal criDcal criDcal Upper Pine -

Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021

Pennsylvania Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021 Length County of Mouth Water Trib To Wild Trout Limits Lower Limit Lat Lower Limit Lon (miles) Adams Birch Run Long Pine Run Reservoir Headwaters to Mouth 39.950279 -77.444443 3.82 Adams Hayes Run East Branch Antietam Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.815808 -77.458243 2.18 Adams Hosack Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.914780 -77.467522 2.90 Adams Knob Run Birch Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.950970 -77.444183 1.82 Adams Latimore Creek Bermudian Creek Headwaters to Mouth 40.003613 -77.061386 7.00 Adams Little Marsh Creek Marsh Creek Headwaters dnst to T-315 39.842220 -77.372780 3.80 Adams Long Pine Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Long Pine Run Reservoir 39.942501 -77.455559 2.13 Adams Marsh Creek Out of State Headwaters dnst to SR0030 39.853802 -77.288300 11.12 Adams McDowells Run Carbaugh Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.876610 -77.448990 1.03 Adams Opossum Creek Conewago Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.931667 -77.185555 12.10 Adams Stillhouse Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.915470 -77.467575 1.28 Adams Toms Creek Out of State Headwaters to Miney Branch 39.736532 -77.369041 8.95 Adams UNT to Little Marsh Creek (RM 4.86) Little Marsh Creek Headwaters to Orchard Road 39.876125 -77.384117 1.31 Allegheny Allegheny River Ohio River Headwater dnst to conf Reed Run 41.751389 -78.107498 21.80 Allegheny Kilbuck Run Ohio River Headwaters to UNT at RM 1.25 40.516388 -80.131668 5.17 Allegheny Little Sewickley Creek Ohio River Headwaters to Mouth 40.554253 -80.206802 -

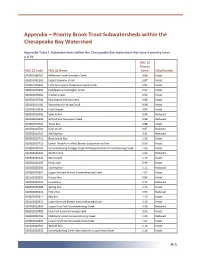

Appendix – Priority Brook Trout Subwatersheds Within the Chesapeake Bay Watershed

Appendix – Priority Brook Trout Subwatersheds within the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Appendix Table I. Subwatersheds within the Chesapeake Bay watershed that have a priority score ≥ 0.79. HUC 12 Priority HUC 12 Code HUC 12 Name Score Classification 020501060202 Millstone Creek-Schrader Creek 0.86 Intact 020501061302 Upper Bowman Creek 0.87 Intact 020501070401 Little Nescopeck Creek-Nescopeck Creek 0.83 Intact 020501070501 Headwaters Huntington Creek 0.97 Intact 020501070502 Kitchen Creek 0.92 Intact 020501070701 East Branch Fishing Creek 0.86 Intact 020501070702 West Branch Fishing Creek 0.98 Intact 020502010504 Cold Stream 0.89 Intact 020502010505 Sixmile Run 0.94 Reduced 020502010602 Gifford Run-Mosquito Creek 0.88 Reduced 020502010702 Trout Run 0.88 Intact 020502010704 Deer Creek 0.87 Reduced 020502010710 Sterling Run 0.91 Reduced 020502010711 Birch Island Run 1.24 Intact 020502010712 Lower Three Runs-West Branch Susquehanna River 0.99 Intact 020502020102 Sinnemahoning Portage Creek-Driftwood Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.03 Intact 020502020203 North Creek 1.06 Reduced 020502020204 West Creek 1.19 Intact 020502020205 Hunts Run 0.99 Intact 020502020206 Sterling Run 1.15 Reduced 020502020301 Upper Bennett Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.07 Intact 020502020302 Kersey Run 0.84 Intact 020502020303 Laurel Run 0.93 Reduced 020502020306 Spring Run 1.13 Intact 020502020310 Hicks Run 0.94 Reduced 020502020311 Mix Run 1.19 Intact 020502020312 Lower Bennett Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.13 Intact 020502020403 Upper First Fork Sinnemahoning Creek 0.96 -

Low-Flow, Base-Flow, and Mean-Flow Regression Equations for Pennsylvania Streams

Low-Flow, Base-Flow, and Mean-Flow Regression Equations for Pennsylvania Streams By Marla H. Stuckey In cooperation with the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection Scientific Investigations Report 2006-5130 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey P. Patrick Leahy, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2006 For sale by U.S. Geological Survey, Information Services Box 25286, Denver Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 For more information about the USGS and its products: Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/ Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to repro- duce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Stuckey, M.H., 2006, Low-flow, base-flow, and mean-flow regression equations for Pennsylvania streams: U.S. Geo- logical Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2006-5130, 84 p. iii Contents Abstract. 1 Introduction . 1 Purpose and Scope . 2 Previous Investigations . 2 Physiography and Drainage. 2 Development of Regression Equations . 2 Streamflow-Gaging Stations . 2 Basin Characteristics . 5 Regression Techniques . 5 Low-Flow Regression Equations. 6 Base-Flow Regression Equations. 10 Mean-Flow Regression Equations. 13 Limitations of Regression Equations . 15 Summary . 15 Acknowledgments . 17 References Cited. 17 Appendixes . 19 1. Streamflow-gaging stations used in development of low-flow, base-flow, and mean-flow regression equations for Pennsylvania streams.