Media Freedom in the Shadow of a Coup

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 2020 Editor John Liukkonen Email: [email protected]

KIBITZER ♣♦♥♠ Louisiana Bridge Association January 2020 Editor John Liukkonen email: [email protected] President’s Message January 2020 What is going on at the Bridge Center? Lots of parties and food. So many have joined in to make our holiday season special. Our tacky wear day was fun and should become a yearly occasion. Christmas party and Bridge! Mary LeBlanc your hosting the Christmas party made it a huge success. Our member sponsored Friday Pot Luck Party had the best food and Hunter made a great choice with the Ham and Turkey. Thanks to our Board as they all helped prepare and clean up after the event. Most of us are ready to get back to just playing bridge. I know I am. The Rosenblum Tournament is January 9-12. Don’t forget to vote for the Board of Directors that week (see more election details below.) Susan Beoubay has offered to chair all our tournaments. I don’t know why we are so fortunate to have so many wonderful people willing to volunteer their time and creative abilities. Lowen is ready to help us play better BRIDGE. Class starts Saturday, January 18 at 9:30. See p 4 for more detail on that. I would like to thank everyone for their continued support to make our club the best place to play BRIDGE and make friends. Carolyn Dubois January Events Board of Directors elections *= extra points, no extra fee Starting January 6 —the week of our sectional **=extra points, extra fee tournament—we will hold elections for our Board of Week of Jan 6—vote for Board of Directors Directors. -

Glossary of Bridge Terms

GLOSSARY OF BRIDGE TERMS Alert When your partner makes a conventional bid you must alert this to the opponents by knocking the table (or displaying the ‘Alert’ card if using bidding boxes). Auction Another term for the bidding. Avoidance An attempt to prevent a particular defender from regaining the lead. Balanced A hand containing no void, no singleton and not more than one Hand doubleton. Barrier When planning your opener's rebid, imagine a ‘barrier’ just above your first suit at the next level up. A new suit rebid below the barrier shows 12-15 points (occasionally 16 or 17 points after a 1 level response when opener doesn’t have enough for a jump shift). A new suit rebid above the barrier that isn’t a jump shift shows 16-19 points (also known as a reverse). Blocked A suit is blocked if there is a high card in the short hand that prevents the suit from being cashed. A player will often aim to unblock the suit. Break The way in which the defenders’ cards in a particular suit are divided between their two hands. For example, a 4-2 break indicates that with 6 cards in a suit missing, one defender has 4 cards of the suit and his partner has 2 cards. Also referred to as split. Cash Playing a card that is certain to win the trick. This card is known as a master. Clear a suit Knocking out the opponents’ last stopper in a suit, after which it will be possible to cash one’s tricks in the suit. -

The-Encyclopedia-Of-Cardplay-Techniques-Guy-Levé.Pdf

© 2007 Guy Levé. All rights reserved. It is illegal to reproduce any portion of this mate- rial, except by special arrangement with the publisher. Reproduction of this material without authorization, by any duplication process whatsoever, is a violation of copyright. Master Point Press 331 Douglas Ave. Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5M 1H2 (416) 781-0351 Website: http://www.masterpointpress.com http://www.masteringbridge.com http://www.ebooksbridge.com http://www.bridgeblogging.com Email: [email protected] Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Levé, Guy The encyclopedia of card play techniques at bridge / Guy Levé. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-1-55494-141-4 1. Contract bridge--Encyclopedias. I. Title. GV1282.22.L49 2007 795.41'5303 C2007-901628-6 Editor Ray Lee Interior format and copy editing Suzanne Hocking Cover and interior design Olena S. Sullivan/New Mediatrix Printed in Canada by Webcom Ltd. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 11 10 09 08 07 Preface Guy Levé, an experienced player from Montpellier in southern France, has a passion for bridge, particularly for the play of the cards. For many years he has been planning to assemble an in-depth study of all known card play techniques and their classification. The only thing he lacked was time for the project; now, having recently retired, he has accom- plished his ambitious task. It has been my privilege to follow its progress and watch the book take shape. A book such as this should not to be put into a beginner’s hands, but it should become a well-thumbed reference source for all players who want to improve their game. -

Media Freedom in the Shadow of a Coup Raphael Boleslavsky, Mehdi Shadmehr, and Konstantin Sonin JANUARY 2019

WORKING PAPER · NO. 2019-81 Media Freedom in the Shadow of a Coup Raphael Boleslavsky, Mehdi Shadmehr, and Konstantin Sonin JANUARY 2019 5757 S. University Ave. Chicago, IL 60637 Main: 773.702.5599 bfi.uchicago.edu Media Freedom in the Shadow of a Coup Raphael Boleslavsky∗ Mehdi Shadmehry Konstantin Soninz Abstract Popular protests and palace coups are the two domestic threats to dictators. We show that free media, which informs citizens about their rulers, is a double-edged sword that alleviates one threat, but exacerbates the other. Informed citizens may protest against a ruler, but they may also protest to restore him after a palace coup. In choosing media freedom, the leader trades off these conflicting effects. We develop a model in which citizens engage in a regime change global game, and media freedom is a ruler's instrument for Bayesian persuasion, used to manage the competing risks of coups and protests. A coup switches the status quo from being in the ruler's favor to being against him. This introduces convexities in the ruler's Bayesian persuasion prob- lem, causing him to benefit from an informed citizenry. Rulers tolerate freer press when citizens are pessimistic about them, or coups signal information about them to citizens. Keywords: authoritarian politics, media freedom, protest, coup, global games, Bayesian persuasion, signaling JEL Classification: H00, D82 ∗Department of Economics, University of Miami, 5250 University Dr., Coral Gables, FL 33146. E-mail: [email protected] yHarris School of Public Policy, University of Chicago, and Department of Economics, University of Calgary, 1155 East 60th Street, Chicago 60637. -

15Th WORLD BRIDGE GAMES Wroclaw, Poland • 3Rd – 17Th September 2016

15th WORLD BRIDGE GAMES wroclaw, poland • 3rd – 17th september 2016 Coordinator: Jean-Paul Meyer • Editor: Brent Manley Co-editors: Jos Jacobs, Micke Melander, Ram Soffer, David Stern, Marek Wojcicki Lay out Editor: Monika Kümmel • Photographer: Ron Tacchi Issue NDailyo. 13 Bulletin Friday, 16th September 2016 IT’S ONE ON ONE FOR TITLE HOPEFULS Young bridge players work with some of the 22,000 playing cards strung together in Plac Solny on Thursday. Story on page 4 Eight teams will begin battle today for four championships, and three countries have chances to emerge with two world titles. France (Seniors and Women’s), the Contents Netherlands (Open and Mixed) and USA (Seniors and Women’s) each have two Results . .2 chances for gold. The match between USA and France in the Women’s will be a rematch from last year in Chennai, where the French prevailed. BBO Schedule . .4 The most dramatic of the victories on Thursday was staged by Monaco, who trailed Fun with bridge in Salt Square 4 by 46 IMPs at one point against Spain but rallied in the second half to emerge with Hands and Match Reports . .5 a 6-IMP win. Poland, one of the favorites in the Open, fell behind against a surging Dutch team The Polish Corner . .26 and never recovered, losing by 78. Prize Giving and Closing Ceremony The ceremony will take place on Saturday 17th in the auditorium, beginning Today’s Programme Today’s Programme at 20:00. It will be followed by a reception at the “La Pergola” restaurant. Players who wish to attend the dinner must collect their invitation card at Pairs: Teams: the Hospitality Desk. -

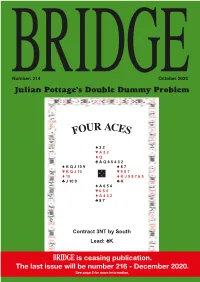

FOUR ACES Could Have Done More Safely

Number: 214 October 2020 BRIDGEJulian Pottage’s Double Dummy Problem UR ACE FO S ♠ 3 2 ♥ A 3 2 ♦ Q ♣ A Q 6 5 4 3 2 ♠ K Q J 10 9 ♠ 8 7 ♥ N ♥ K Q J 10 W E 9 8 7 ♦ 10 S ♦ K J 9 8 7 6 5 ♣ J 10 9 ♣ K ♠ A 6 5 4 ♥ 6 5 4 ♦ A 4 3 2 ♣ 8 7 Contract 3NT by South Lead: ♠K BRIDGE is ceasing publication. The last issueThe will answer be will benumber published on page 216 4 next - month.December 2020. See page 5 for more information. A Sally Brock Looks At Your Slam Bidding Sally’s Slam Clinic Where did we go wrong? Slam of the month Another regular contributor to these Playing standard Acol, South would This month’s hand was sent in by pages, Alex Mathers, sent in the open 2♣, but whatever system was Roger Harris who played it with his following deal which he bid with played it is likely that he would then partner Alan Patel at the Stratford- his partner playing their version of rebid 2NT showing 23-24 points. It is upon-Avon online bridge club. Benjaminised Acol: normal to play the same system after 2♣/2♦ – negative – 2NT as over an opening 2NT, so I was surprised North Dealer South. Game All. Dealer West. Game All. did not use Stayman. In my view the ♠ A 9 4 ♠ J 9 8 correct Acol sequence is: ♥ K 7 6 ♥ A J 10 6 ♦ 2 ♦ K J 7 2 West North East South ♣ A 9 7 6 4 2 ♣ 8 6 Pass Pass Pass 2♣ ♠ Q 10 8 6 3 ♠ J 7 N ♠ Q 4 3 ♠ 10 7 5 2 Pass 2♦ Pass 2NT ♥ Q 9 ♥ 10 8 5 4 2 W E ♥ 7 4 3 N ♥ 9 8 5 2 Pass 3♣ Pass 3♦ ♦ Q J 10 9 5 ♦ K 8 7 3 S W E ♦ 8 5 4 ♦ Q 9 3 Pass 6NT All Pass ♣ 8 ♣ Q 5 S ♣ Q 10 9 4 ♣ J 5 Once South has shown 23 HCP or so, ♠ K 5 2 ♠ A K 6 North knows the values are there for ♥ A J 3 ♥ K Q slam. -

42, the Erosion of Civilian Control Of

'The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the US Air Force, Department of Defense or the US Government.'" UNITED STATES AIR FORCE ACADEMY Develops and inspires air and space leaders with vision for tomorrow. The Erosion of Civilian Control of the Military in the United States Today Richard H. Kohn University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill The Harmon Memorial Lectures in Military History Number Forty-Two United States Air Force Academy Colorado 1999 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402 Lieutenant General Hubert Reilly Harmon Lieutenant General Hubert R. Harmon was one of several distinguished Army officers to come from the Harmon family. His father graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1880 and later served as Commandant of Cadets at the Pennsylvania Military Academy. Two older brothers, Kenneth and Millard, were members of the West Point class of 1910 and 1912, respectively. The former served as Chief of the San Francisco Ordnance District during World War II; the latter reached flag rank and was lost over the Pacific during World War II while serving as Commander of the Pacific Area Army Air Forces. Hubert Harmon, born on April 3, 1882, in Chester, Pennsylvania, followed in their footsteps and graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1915. Dwight D. Eisenhower also graduated in this class, and nearly forty years later the two worked together to create the new United States Air Force Academy. Harmon left West Point with a commission in the Coast Artillery Corps, but he was able to enter the new Army air branch the following year. -

HIGH INTENSITY SRF PROTON LINAC WORKSHOP (VUGRAPHS) S° £*§!* 2 5 Itfs § •S^2,§ I?

& o riF~ 9srosr29?~ i/^^ 1A-UR- 95 "3 3 §-5%. TITLE: HIGH INTENSITY SRF PROTON LINAC WORKSHOP (VUGRAPHS) S° £*§!* 2 5 ItfS § •s^2,§ I? AUTHOR(S): •-(3D CD « Brian A. Rusnak and AOT-1 o g CD a II Several external authors So --I; !-' i J*> a . c ca a g E a a o..2 (500 double-sided a 4> ,0 u £ 00 O •" « 6*3 o g • vugraphs) TS S 2 c _. ,1 o. «> ""S8SI Is M E t S II 'S « O O Si * 5- II "S2 O« g B.to & S - p l'i is 8 » s* « '3 o s ii 1? SUBMITTED TO: High Intensity SRP Proton Linac Workshop. •?« I Santa Fe, NM •It! •5 -c May 7-10,1995 o o li §2 n J3 a E f£§iI 8f 11I NATIONAL LABORATORY Los Alamos National Laboratory, an affirmative action/equal opportunity employer, is operated by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy under contract W-7405-ENG-36. By acceptance of this article, the publisher recognizes that the U.S. Government retains a nonexclusive, royalty-free license to publish or reproduce the published form of this contribution, or to allow others to do so, for U.S. Government purposes. The Los Alamos National Laboratory requests that the publisher identify this article as work performed under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy. Form No. 836 R5 DISTRIBUTION OF THIS DOCUMENT IS UNLIMITED ST 262910.91 DISCLAIMER Portions of this document may be illegible in electronic image products. -

Make Mine a Madeira Brother Xavier's Double Bridge with Larry Cohen

A NEW First Edition BRIDGE MAGAZINE January 2018 Make Mine a Madeira Brother Xavier’s Double Bridge With Larry Cohen A NEW BRIDGE MAGAZINE – JANUARY 2018 Under Starter’s Orders take many forms – I have already mentioned Welcome to the pages of A New Bridge Magazine. the possibility of being When Bridge Magazine announced a few weeks ago linked to a column A NEW that it was ceasing publication Ron Tacchi and I within the magazine decided that we could not allow the world’s bridge and you will see from playing public to be deprived of their monthly dose this issue that this is of bridge from some of the world’s best writers. already popular. There BRIDGEAs it appears that a subscription based magazine is also the possibility of linking directly to the title. was no longer a suitable model we have decided Thirdly by becoming a Friend of the magazine. that A New Bridge Magazine will be totally free. That would involve a donation. Anyone donating In the Internet age that we live in this enables us £500 would become a Golden Friend. MAGAZINE to make it available instantaneously to anyone in the world who cares to read it. If you would like to discuss any of the above con- tact me at: [email protected] In order to meet our production costs we are relying on sponsorship, advertising revenue and Ask not what A New Bridge Magazine can do donations. for you – ask what you can do for A New Bridge Editor: Magazine. Mark Horton Sponsorship can come in many forms – one that is proving popular is the sponsorship of a particular Advertising: Dramatis Personae Mark Horton column - as you will see from the association of FunBridge with Misplay these Hands with Me and Now let me tell you something about what you can Photographer: Master Point Press with The Bidding Battle. -

The Elimination Endplay ♠ A2 ♥ AJ954 Advanced Declarer Play Is More an Art Than a ♦ 76 Science

The elimination endplay ♠ A2 ~ AJ954 Advanced declarer play is more an art than a } 76 science. There are coups, squeezes, and endplays, | Q987 with goofy names like `winkle squeeze' and `den- ♠ QJ1098 ♠ K7654 N tist coup,' invented so that after pulling one off ~ KQ ~ 32 WE by accident and having it explained by the local } 543 } AK2 S expert bridge player, you can say to your friends: | AJ4 | K102 `I thought I was done for, until I caught Sharon ♠ 3 in a double wombat. Boy was she livid!' We'll ~ 10876 start with the elimination endplay. Put yourself } QJ1098 in West's shoes for this deal: | 653 This play succeeds because declarer is able to ♠ QJ1098 ♠ K7654 void himself in hearts and diamonds before forc- ~ KQ ~ 32 ing the opponents to win the lead. It is crucial WE } 543 } AK2 to clear the hearts before the diamonds: if we | AJ4 | K102 play on diamonds first, the opponents can cash the ~A and put declarer back in with a heart in the end position. West North East South 1♠ Pass 2NTy Pass Can the defense do anything to prevent this? 4♠ Pass Pass Pass If they attack the diamond suit three times, be- fore declarer has shed his hearts, the endplay will y Jacoby. fail. In this example, North can play diamonds whenever he is on lead, but since he has only two diamonds, the endplay cannot be stopped. Even North leads the }7. It appears that we need to if the defense manage to thwart the possibility guess the location of the |Q to avoid losing one of an endplay (if North had a third diamond, for trick in each suit. -

Vugraph Matches

Bulletin 8 Friday, 20 July 2007 QUALIFYING RACES HOT UP The vugraph theatre - the only cool place in the Palazzo Italy had another good day in the Junior Series, taking a maximum against Austria then winning 18-12 against early leaders Norway. Netherlands, however, had a good win over France and crept a point closer in second VUGRAPH place. The battle for the qualifying places for next year’s World Champi- onships is hotting up. Italy leads with 338 VPs, from Netherlands 328.5, MATCHES Poland 311, Germany 308, Norway 298, Russia 291.5, Denmark 285, France 283, England 272. Poland is looking very good for the Schools Championship. Though the Poles lost the morning match 10-20 toTurkey, perhaps the performance of France - England (Schools) 10.00 the day from the Turks, 25 against Wales and 23 against Israel left them with Poland - Russia (Juniors) 14.00 a comfortable lead. Poland leads with 205 VPs, from England on 176, Swe- den 175, Norway 172, France 170, Bulgaria 166.5, and Germany 158.5. France - Norway (Juniors) 17.30 21st EUROPEAN YOUTH TEAM CHAMPIONSHIPS Jesolo, Italy JUNIOR TEAMS TODAY’S RESULTS PROGRAM ROUND 16 ROUND 18 Match IMP’s VP’s 1 DENMARK GREECE 1 CZECH REPUBLIC GREECE 66 - 34 22 - 8 2 RUSSIA HUNGARY 2 BELGIUM ROMANIA 51 - 54 14 - 16 3 GERMANY POLAND 3 ENGLAND SWEDEN 66 - 56 17 - 13 4 ITALY ENGLAND 4 POLAND SLOVAKIA 110 - 21 25 - 0 5 PORTUGAL BELGIUM 5 HUNGARY CROATIA 46 - 8 23 - 7 6 NETHERLANDS CZECH REPUBLIC 6 DENMARK TURKEY 47 - 14 22 - 8 7 FRANCE ROMANIA 7 RUSSIA LATVIA 57 - 39 19 - 11 8 GERMANY SCOTLAND 46 - 27 19 - -

The Ocbl Journal in Your Mailbox

OCBL JOURNAL Issue N. 101. Thursday, 3 June, 2021 Schedule Today OCBL OPEN LEAGUE: the Final will be OCBL JUNE CUP ROUND 8. 16.30 CEST / 10.30 a.m. EDT DONNER vs BLACK Donner VS Black The second (and last) half of the Semifinals of the OCBL Open League was played yesterday. Apres-Br Champs VS Compton VUGRAPH Orca VS Hungary In both matches, the team who was slightly behind managed to recover and advance to the Final. Ferguson VS Skeidar Calcio & Football VS Tilly In the match Austromany vs Black, Black started the second half of the Semifinal 11.1 IMPs Scorway VS Harris behind. The match ended 88-68.1 IMPs (+19.9) for the English team. Leslie VS Team International Greenspan VS Sugi In the match Donner vs De Michelis, Donner started the second half of the Semifinal 7.1 IMPs Lion VS Zhao behind. The match ended 65-58.1 IMPs (+6.9) for the American team, who passed ROUND 9. 19.00 CEST / 1.00 p.m. EDT their opponents in the very last board in an exciting finish. Donner VS Zhao VUGRAPH Apres-Br Champs VS Black Orca VS Compton Ferguson VS Hungary OCBL JUNE CUP: Calcio & Football VS Skeidar Two more rounds, then... the cut Scorway VS Tilly Leslie VS Harris The last two rounds of the qualification stage of the OCBL June Cup will be played today. Greenspan VS Team International Then, the top 4 Teams from each group will advance to the K.O. Lion VS Sugi (Quarterfinal, Semifinal, and Final - one session of 16 boards each).