Beginning Bridge Lessons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pinochle & Bezique

Pinochle & Bezique by MeggieSoft Games User Guide Copyright © MeggieSoft Games 1996-2004 Pinochle & Bezique Copyright ® 1996-2005 MeggieSoft Games All rights reserved. No parts of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means - graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage and retrieval systems - without the written permission of the publisher. Products that are referred to in this document may be either trademarks and/or registered trademarks of the respective owners. The publisher and the author make no claim to these trademarks. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this document, the publisher and the author assume no responsibility for errors or omissions, or for damages resulting from the use of information contained in this document or from the use of programs and source code that may accompany it. In no event shall the publisher and the author be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damage caused or alleged to have been caused directly or indirectly by this document. Printed: February 2006 Special thanks to: Publisher All the users who contributed to the development of Pinochle & MeggieSoft Games Bezique by making suggestions, requesting features, and pointing out errors. Contents I Table of Contents Part I Introduction 6 1 MeggieSoft.. .Games............ .Software............... .License............. ...................................................................................... 6 2 Other MeggieSoft............ ..Games.......... -

Introducion to Duplicate

INTRODUCTION to DUPLICATE INTRODUCTION TO DUPLICATE BRIDGE This book is not about how to bid, declare or defend a hand of bridge. It assumes you know how to do that or are learning how to do those things elsewhere. It is your guide to playing Duplicate Bridge, which is how organized, competitive bridge is played all over the World. It explains all the Laws of Duplicate and the process of entering into Club games or Tournaments, the Convention Card, the protocols and rules of player conduct; the paraphernalia and terminology of duplicate. In short, it’s about the context in which duplicate bridge is played. To become an accomplished duplicate player, you will need to know everything in this book. But you can start playing duplicate immediately after you read Chapter I and skim through the other Chapters. © ACBL Unit 533, Palm Springs, Ca © ACBL Unit 533, 2018 Pg 1 INTRODUCTION to DUPLICATE This book belongs to Phone Email I joined the ACBL on ____/____ /____ by going to www.ACBL.com and signing up. My ACBL number is __________________ © ACBL Unit 533, 2018 Pg 2 INTRODUCTION to DUPLICATE Not a word of this book is about how to bid, play or defend a bridge hand. It assumes you have some bridge skills and an interest in enlarging your bridge experience by joining the world of organized bridge competition. It’s called Duplicate Bridge. It’s the difference between a casual Saturday morning round of golf or set of tennis and playing in your Club or State championships. As in golf or tennis, your skills will be tested in competition with others more or less skilled than you; this book is about the settings in which duplicate happens. -

Slam Bidding Lesson

Slam Bidding and Modified Scroll Bids By Neil H. Timm In this Bridge Bit, I explore more fully Slam bidding techniques, some old and some perhaps new. To reach a small slam, the partnership should have roughly thirty-three Bergen points. In addition to a trump fit and count, slams require controls (aces, kings, voids, and singletons). The more controls between the partners, the easier the slam. To evaluate whether or not the partnership has the required controls, one uses cuebids with perhaps the 5NT trump ask bid (Grand Slam Force), and Blackwood Conventions. Blackwood Conventions reveal how many aces and kings, while cuebidding or control showing bids reveal where they reside. To make a slam, one usually requires first-round control in three suits and second round control in the fourth suit. It is possible to make a slam missing two aces, provided the missing ace is opposite a void, and the second missing ace is replaced by or is opposite a second-round control (a king or a singleton). When looking for a possible slam, one often asks the following questions. 1. What cards should my partner have to be able to make a slam? 2. How may I obtain the required information? 3. Are there any bidding techniques or conventions that I can use to obtain the required information? 4. If my partner does not have the required cards for a slam, can I stop short of slam, and if not is the risk of going down worth it? We shall review techniques to help the partnership find the required information for making a slam! However, with some hands one needs only to count points to reach a slam. -

Things You Might Like to Know About Duplicate Bridge

♠♥♦♣ THINGS YOU MIGHT LIKE TO KNOW ABOUT DUPLICATE BRIDGE Prepared by MayHem Published by the UNIT 241 Board of Directors ♠♥♦♣ Welcome to Duplicate Bridge and the ACBL This booklet has been designed to serve as a reference tool for miscellaneous information about duplicate bridge and its governing organization, the ACBL. It is intended for the newer or less than seasoned duplicate bridge players. Most of these things that follow, while not perfectly obvious to new players, are old hat to experienced tournaments players. Table of Contents Part 1. Expected In-behavior (or things you need to know).........................3 Part 2. Alerts and Announcements (learn to live with them....we have!)................................................4 Part 3. Types of Regular Events a. Stratified Games (Pairs and Teams)..............................................12 b. IMP Pairs (Pairs)...........................................................................13 c. Bracketed KO’s (Teams)...............................................................15 d. Swiss Teams and BAM Teams (Teams).......................................16 e. Continuous Pairs (Side Games)......................................................17 f. Strategy: IMPs vs Matchpoints......................................................18 Part 4. Special ACBL-Wide Events (they cost more!)................................20 Part 5. Glossary of Terms (from the ACBL website)..................................25 Part 6. FAQ (with answers hopefully).........................................................40 Copyright © 2004 MayHem 2 Part 1. Expected In-Behavior Just as all kinds of competitive-type endeavors have their expected in- behavior, so does duplicate bridge. One important thing to keep in mind is that this is a competitive adventure.....as opposed to the social outing that you may be used to at your rubber bridge games. Now that is not to say that you can=t be sociable at the duplicate table. Of course you can.....and should.....just don=t carry it to extreme by talking during the auction or play. -

Bernard Magee's Acol Bidding Quiz

Number: 178 UK £3.95 Europe €5.00 October 2017 Bernard Magee’s Acol Bidding Quiz This month we are dealing with hands when, if you choose to pass, the auction will end. You are West in BRIDGEthe auctions below, playing ‘Standard Acol’ with a weak no-trump (12-14 points) and four-card majors. 1. Dealer North. Love All. 4. Dealer West. Love All. 7. Dealer North. Love All. 10. Dealer East. E/W Game. ♠ 2 ♠ A K 3 ♠ A J 10 6 5 ♠ 4 2 ♥ A K 8 7 N ♥ A 8 7 6 N ♥ 10 9 8 4 3 N ♥ K Q 3 N W E W E W E W E ♦ J 9 8 6 5 ♦ A J 2 ♦ Void ♦ 7 6 5 S S S S ♣ Q J 3 ♣ Q J 6 ♣ A 7 4 ♣ K Q J 6 5 West North East South West North East South West North East South West North East South Pass Pass Pass 1♥ 1♠ Pass Pass 1♣ 2♦1 Pass 1♥ 1♠ ? ? Pass Dbl Pass Pass 2♣ 2♠ 3♥ 3♠ ? 4♥ 4♠ Pass Pass 1Weak jump overcall ? 2. Dealer North. Love All. 5. Dealer West. Love All. 8. Dealer East. Love All. 11. Dealer North. N/S Game. ♠ 2 ♠ A K 7 6 5 ♠ A 7 6 5 4 3 ♠ 4 3 2 ♥ A J N ♥ 4 N ♥ A K 3 N ♥ A 7 6 N W E W E W E W E ♦ 8 7 2 ♦ A K 3 ♦ 2 ♦ A 8 7 6 4 S S S S ♣ K Q J 10 5 4 3 ♣ J 10 8 2 ♣ A 5 2 ♣ 7 6 West North East South West North East South West North East South West North East South Pass Pass Pass 1♠ 2♥ Pass Pass 3♦ Pass 1♣ 3♥ Dbl ? ? Pass 3♥ Pass Pass 4♥ 4♠ Pass Pass ? ? 3. -

Acol Bidding Notes

SECTION 1 - INTRODUCTION The following notes are designed to help your understanding of the Acol system of bidding and should be used in conjunction with Crib Sheets 1 to 5 and the Glossary of Terms The crib sheets summarise the bidding in tabular form, whereas these notes provide a fuller explanation of the reasons for making particular bids and bidding strategy. These notes consist of a number of short chapters that have been structured in a logical order to build on the things learnt in the earlier chapters. However, each chapter can be viewed as a mini-lesson on a specific area which can be read in isolation rather than trying to absorb too much information in one go. It should be noted that there is not a single set of definitive Acol ‘rules’. The modern Acol bidding style has developed over the years and different bridge experts recommend slightly different variations based on their personal preferences and playing experience. These notes are based on the methods described in the book The Right Way to Play Bridge by Paul Mendelson, which is available at all good bookshops (and some rubbish ones as well). They feature a ‘Weak No Trump’ throughout and ‘Strong Two’ openings. +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ INDEX Section 1 Introduction Chapter 1 Bidding objectives & scoring Chapter 2 Evaluating the strength of your hand Chapter 3 Evaluating the shape of your hand . Section 2 Balanced Hands Chapter 21 1NT opening bid & No Trumps responses Chapter 22 1NT opening bid & suit responses Chapter 23 Opening bids with stronger balanced hands Chapter 24 Supporting responder’s major suit Chapter 25 2NT opening bid & responses Chapter 26 2 Clubs opening bid & responses Chapter 27 No Trumps responses after an opening suit bid Chapter 28 Summary of bidding with Balanced Hands . -

Hall of Fame Takes Five

Friday, July 24, 2009 Volume 81, Number 1 Daily Bulletin Washington, DC 81st Summer North American Bridge Championships Editors: Brent Manley and Paul Linxwiler Hall of Fame takes five Hall of Fame inductee Mark Lair, center, with Mike Passell, left, and Eddie Wold. Sportsman of the Year Peter Boyd with longtime (right) Aileen Osofsky and her son, Alan. partner Steve Robinson. If standing ovations could be converted to masterpoints, three of the five inductees at the Defenders out in top GNT flight Bridge Hall of Fame dinner on Thursday evening The District 14 team captained by Bob sixth, Bill Kent, is from Iowa. would be instant contenders for the Barry Crane Top Balderson, holding a 1-IMP lead against the They knocked out the District 9 squad 500. defending champions with 16 deals to play, won captained by Warren Spector (David Berkowitz, Time after time, members of the audience were the fourth quarter 50-9 to advance to the round of Larry Cohen, Mike Becker, Jeff Meckstroth and on their feet, applauding a sterling new class for the eight in the Grand National Teams Championship Eric Rodwell). The team was seeking a third ACBL Hall of Fame. Enjoying the accolades were: Flight. straight win in the event. • Mark Lair, many-time North American champion Five of the six team members are from All four flights of the GNT – including Flights and one of ACBL’s top players. Minnesota – Bob and Cynthia Balderson, Peggy A, B and C – will play the round of eight today. • Aileen Osofsky, ACBL Goodwill chair for nearly Kaplan, Carol Miner and Paul Meerschaert. -

Last Updated July 2020 Changes from Last Version Highlighted in Yellow Author Title Date Edition Cover Sgnd Comments

Last updated July 2020 Changes from last version highlighted in yellow Author Title Date Edition Cover Sgnd Comments ANON THE LAWS OF ROYAL AUCTION BRIDGE 1914 1st Card Small, stitched booklet with red covers ABERN Wendell & FIELDER Jarvis BRIDGE IS A CONTACT SPORT 1995 1st Card ABRAHAMS Gerald BRAINS IN BRIDGE 1962 1st No DW Ditto 1962 1st DW Ex-G C H Fox Library "A C B" AUCTION BRIDGE FOR BEGINNERS AND OTHERS 1929 Rev ed No DW ACKERSLEY Chris THE BRIDGING OF TROY 1986 1st DW Ex-G C H Fox Library ADAMS J R DEFENCE AT AUCTION BRIDGE 1930 1st No DW AINGER Simon SIMPLE CONVENTIONS FOR THE ACOL SYSTEM 1995 1st Card ALBARRAN Pierre & JAIS Pierre HOW TO WIN AT RUBBER BRIDGE 1961 1st UK No DW Ditto 1961 1st UK DW Ex-G C H Fox Library ALDER Philip YOU CAN PLAY BRIDGE 1983 1st Card 1st was hb ALLEN David THE PHONEY CLUB The Cleveland Club System 1992 1st DW Ex-G C H Fox Library Ditto 1992 1st DW AMSBURY Joe BRIDGE: BIDDING NATURALLY 1979 1st DW Ditto 1979 1st DW Ex-G C H Fox Library ANDERTON Philip BRIDGE IN 20 LESSONS 1961 1st DW Ex-G C H Fox Library Ditto 1961 1st DW PLAY BRIDGE 1967 1st DW Ditto 1967 1st DW Ex-G C H Fox Library ARKELL Reginald BRIDGE WITHOUT SIGHS 1934 2nd No DW Ditto 1934 2nd No dw ARMSTRONG, Len The Final Deal 1995 1st Paper AUHAGEN Ulrich DAS GROBE BUCH VOM BRIDGE 1973 1st DW Ex-Rixi Markus Library with compliment slip "BADSWORTH" BADSWORTH ON BRIDGE 1903 1st Boards Ex-G C H Fox Library aeg BADSWORTH ON BRIDGE 1903 1st Boards Aeg; IN PLASTIC PROTECTIVE SLEEVE AUCTION BRIDGE AND ROYAL AUCTION 1913 2nd Boards BAILEY Alan ABRIDGED -

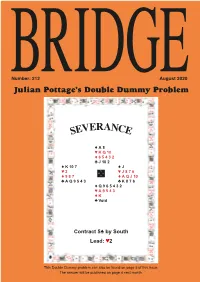

SEVERANCE © Mr Bridge ( 01483 489961

Number: 212 August 2020 BRIDGEJulian Pottage’s Double Dummy Problem VER ANCE SE ♠ A 8 ♥ K Q 10 ♦ 6 5 4 3 2 ♣ J 10 2 ♠ K 10 7 ♠ J ♥ N ♥ 2 W E J 8 7 6 ♦ 9 8 7 S ♦ A Q J 10 ♣ A Q 9 5 4 3 ♣ K 8 7 6 ♠ Q 9 6 5 4 3 2 ♥ A 9 5 4 3 ♦ K ♣ Void Contract 5♠ by South Lead: ♥2 This Double Dummy problem can also be found on page 5 of this issue. The answer will be published on page 4 next month. of the audiences shown in immediately to keep my Bernard’s DVDs would put account safe. Of course that READERS’ their composition at 70% leads straight away to the female. When Bernard puts question: if I change my another bidding quiz up on Mr Bridge password now, the screen in his YouTube what is to stop whoever session, the storm of answers originally hacked into LETTERS which suddenly hits the chat the website from doing stream comes mostly from so again and stealing DOUBLE DOSE: Part One gives the impression that women. There is nothing my new password? In recent weeks, some fans of subscriptions are expected wrong in having a retinue. More importantly, why Bernard Magee have taken to be as much charitable The number of occasions haven’t users been an enormous leap of faith. as they are commercial. in these sessions when warned of this data They have signed up for a By comparison, Andrew Bernard has resorted to his breach by Mr Bridge? website with very little idea Robson’s website charges expression “Partner, I’m I should add that I have of what it will look like, at £7.99 plus VAT per month — excited” has been thankfully 160 passwords according a ‘founder member’s’ rate that’s £9.59 in total — once small. -

January 2020 Editor John Liukkonen Email: [email protected]

KIBITZER ♣♦♥♠ Louisiana Bridge Association January 2020 Editor John Liukkonen email: [email protected] President’s Message January 2020 What is going on at the Bridge Center? Lots of parties and food. So many have joined in to make our holiday season special. Our tacky wear day was fun and should become a yearly occasion. Christmas party and Bridge! Mary LeBlanc your hosting the Christmas party made it a huge success. Our member sponsored Friday Pot Luck Party had the best food and Hunter made a great choice with the Ham and Turkey. Thanks to our Board as they all helped prepare and clean up after the event. Most of us are ready to get back to just playing bridge. I know I am. The Rosenblum Tournament is January 9-12. Don’t forget to vote for the Board of Directors that week (see more election details below.) Susan Beoubay has offered to chair all our tournaments. I don’t know why we are so fortunate to have so many wonderful people willing to volunteer their time and creative abilities. Lowen is ready to help us play better BRIDGE. Class starts Saturday, January 18 at 9:30. See p 4 for more detail on that. I would like to thank everyone for their continued support to make our club the best place to play BRIDGE and make friends. Carolyn Dubois January Events Board of Directors elections *= extra points, no extra fee Starting January 6 —the week of our sectional **=extra points, extra fee tournament—we will hold elections for our Board of Week of Jan 6—vote for Board of Directors Directors. -

Solving an Esoteric Card Game with Reinforcement Learning

Solving an Esoteric Card Game with Reinforcement Learning Andrew S. Dallas Stanford University, Stanford, CA, 94305 A learning strategy was developed to learn optimal policies for the card game Somerset and to develop a prediction of what score to expect given an initial hand. Somerset is a trick- taking, imperfect information game similar to the game Euchre. The state and action space of the game is intractably large, so an approximation to the state and action space is used. A Q- learning algorithm is used to learn the policies and impact of using eligibility traces on the learning algorithm’s performance is examined. The learning algorithm showed moderate improvement over a random strategy, and the learned Q-values revealed predictions that could be made on the final score based on the opening deal. I. Introduction Somerset is a four-player, trick-taking card game similar to Euchre. The game has a variety of decisions that must be made with imperfect information. This work aims to find an ideal decision-making strategy for the game that can be used to inform and estimate how a player might perform once the cards have been dealt. The rules to the game will be described here briefly to provide context for the methodology employed, and a more detailed set of rules can be found in Ref. [1]. Somerset is played with a custom deck of cards. Instead of traditional suits of hearts and spades, there are numerical suits of 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12. There are n+1 cards of each numerical suit n with unique numerator non-negative integers up to the suit value denominator. -

BULLETIN Editorial

THE INTERNATIONAL BRIDGE PRESS ASSOCIATION Editor: John Carruthers This Bulletin is published monthly and circulated to around 400 members of the International Bridge Press Association comprising the world’s leading journalists, authors and editors of news, books and articles about contract bridge, with an estimated readership of some 200 million people BULLETIN who enjoy the most widely played of all card games. www.ibpa.com No. 563 Year 2011 Date December 10 President: PATRICK D JOURDAIN Editorial 8 Felin Wen, Rhiwbina ACBL tournaments are noted for their ability to handle walk-up entries, even in elite Cardiff CF14 6NW, WALES UK (44) 29 2062 8839 events with hundreds of tables. Only events which require seeding of teams require [email protected] some sort of pre-tournament entry. For all other events, entries are accepted up until Chairman: game time. PER E JANNERSTEN Nevertheless, there are some areas that can be improved upon and these were evident Banergatan 15 SE-752 37 Uppsala, SWEDEN in Seattle at the Fall NABC. The first was in broadcasting the events over BBO. The main (46) 18 52 13 00 events at the Fall Nationals are the Reisinger, the Blue Ribbon Pairs (each three days in [email protected] length), the Open Teams (Board-a-Match) and the Open Pairs (each two days long). Executive Vice-President: There are also big events for seniors, juniors and women, the biggest of which is the JAN TOBIAS van CLEEFF Senior Knockout Teams. So we had ten days of top-flight competition – unfortunately, Prinsegracht 28a only three days’ worth was broadcast on BBO (semifinals, one match only, and finals of 2512 GA The Hague, NETHERLANDS the Senior KO and the third day of the Reisinger).