This Is an Adaptation of the Report Currently in the HAER Collection at the Library of Congress to Illustrate the Outline Format: Engineering Structures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cta 2016 Historical Calendar Cta 2016 January

cta 2016 Historical Calendar cta 2016 January Chicago Motor Coach Company (CMC) bus #434, manufactured by the Ford Motor Company, was part of a fleet of buses operated by the Chicago Motor Coach Company, one of the predecessor transit companies that were eventually assimilated into the Chicago Transit Authority. The CMC originally operated buses exclusively on the various park boulevards in Chicago, and became known by the marketing slogan, “The Boulevard Route.” Later, service was expanded to operate on some regular streets not served by the Chicago Surface Lines, particularly on the fringes of the city. Chicagoans truly wanted a unified transit system, and it was for this reason that the Chicago Transit Authority was established by charter in 1945. The CMC was not one of the initial properties purchased that made up CTA’s inaugural services on October 1, 1947; however, it was bought by CTA in 1952. D E SABCDEFG: MDecember 2015 T February 2016 W T F S CTA Operations Division S M T W T F S S M T W T F S Group Days Off 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 6 t Alternate day off if you 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 work on this day 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 l Central offices closed 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 27 28 29 30 31 28 29 1New Year’s Day 2 E F G A B C D 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 D E F G A B C 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 C D E F G A B 17 18Martin Luther King, Jr. -

ILLINOIS RAILWAY MUSEUM Locatediat Uniion,Lilinois 60180, in Mchenry County Business Phone: 815 1923-4391 4181 100M \

ILLINOIS Getting to the Museum RAILWAY Madison @94 ~:'~LWAU;/EE ~. - MUSEUM 15 36 94 Located at Union, Illinois in McHenry County FROM CHICAGO Take the Illinois Northwest Tollway (Interstate 90) to U.S. Rte. 20 Marengo exit. Drive Northwesterly on 20, about 4'12 miles, to Union Road. Take Union Road north and east 1mile through town (on Jefferson St.) to Olson Road (end of Jefferson Street). Turn south to the Museum. FROM MILWAUKEE AND EASTERN WISCONSIN Take any road to Illinois Route 176. Follow west, 5'12 miles west of Illinois Route 47 to Union Road. Turn south to Jefferson Street, Union (first street south of the railroad). Take Jefferson Street east to Olson Road (end of Jefferson Street). Turn south to the museum. FROM ROCKFORD AND WESTERN WISCONSIN Take U.S. Route 20 (or Interstate 90 and exit at Route 20 at Cherry Valley-Belvidere) through Marengo. About 1 mile east of Marengo, turn left on Union Road. Take Union Road about 2'/, miles east through Union to Olson Road (end of Union Road-Jefferson Street). Turn south to the Museum. ILLINOIS RAILWAY MUSEUM LocatedIat UniIon,lIlinois 60180, in McHenry County Business Phone: 815 1923-4391 4181 100M \ .... Schedule &c:rimetable STEAM TRAINS ELECTRIC CARS VISIT OUR BOOK SHOP RELIVING THE PAST AT UNION AND REFRESHMENT STAND Remember the mighty sound of the steam lo- . :: The Museum displays and Book Shop are located comotive, the "Clang, Clang," of the streetcar, the in our ancient" 1851 railroad depot. Here you may quiet, breezy ride through the countryside in an acquire postcards, books and a variety of other electric interurban car? All schedules subject to change without notice. -

AAPRCO & RPCA Members Meet to Develop Their Response to New Amtrak Regulations

Volume 1 Issue 6 May 2018 AAPRCO & RPCA members meet to develop their response to new Amtrak regulations Members of the two associations met in New Orleans last week to further develop their response to new regulations being imposed by Amtrak on their members’ private railroad car businesses. Several of those vintage railroad cars were parked in New Orleans Union Station. “Most of our owners are small business people, and these new policies are forcing many of them to close or curtail their operations,” said AAPRCO President Bob Donnelley. “It is also negatively impacting their employees, suppliers and the hospitality industry that works with these private rail car trips,” added RPCA President Roger Fuehring. Currently about 200 private cars travel hundreds of thousands of miles behind regularly scheduled Amtrak trains each year. Along with special train excursions, they add nearly $10 million dollars in high margin revenue annually to the bottom line of the tax-payer subsidized passenger railroad. A 12% rate increase was imposed May 1 with just two weeks’ notice . This followed a longstanding pattern of increases taking effect annually on October 1. Cost data is being developed by economic expert Bruce Horowitz for presentation to Amtrak as are legal options. Members of both organizations are being asked to continue writing their Congress members and engaging the press. Social media is being activated and you are encouraged to follow AAPRCO on Facebook and twitter. Successes on the legislative front include this Congressional letter sent to Amtrak's president and the Board and inclusion of private car and charter train issues in recent hearings. -

Historic Resource Study of Pullman National Monument

Chapter 6 EXISTING CONDITIONS The existing conditions and recent alterations in the Town of Pullman and the factory sites have been addressed well in other documents. The Pullman Historic District Reconnaissance Survey completed in 2013 offers clear and succinct assessments of extant buildings in Pullman. Likewise, the Archaeological Overview & Assessment completed in 2017 covers the current conditions of factory remnants. A draft revised National Historic Landmark nomination for Pullman Historic District, completed in August 1997 and on deposit at Pullman National Monument, includes a list of contributing and non-contributing structures.612 For the purposes of this Historic Resources Report, the existing conditions of built environment cultural resources that are not addressed in the aforementioned documents will be considered briefly for their potential significance for research and interpretation. In addition, this section will consider historical documents valuable for studying change over time in the extant built environment and also strategies for using Pullman’s incredibly rich built environment as primary historical evidence. Figure 6.1 offers a visual map showing the approximate age of extant buildings as well as major buildings missing today that were present on the 1892 Rascher Map. Most obvious from this map are the significant changes in the industrial core. Importantly, many of the 1880s buildings that no longer stand were replaced gradually over the twentieth century at first as part of the Pullman Company’s changing technological needs, then after 1959 as part of deindustrialization and the reinvention of the Calumet region. The vast majority of domestic structures from the Town of Pullman’s original construction survive. -

2017Chicago Transit Authority a Horse Drawn Omnibus, Originally Operated by the Citizen’S Line Circa 1853, Is Displayed at West Shops at Pulaski and Lake

HISTORICAL CALENDAR 2017Chicago Transit Authority A horse drawn omnibus, originally operated by the Citizen’s Line circa 1853, is displayed at West Shops at Pulaski and Lake. These early transit vehicles were quite primitive, barely just a notch above stagecoaches – little more than hard, wooden bench seats were provided on either side of very sparsely appointed coaches, with no heat, light, or other amenities. It is hard to believe that, from such humble beginnings, Chicago would one day have the second largest public transit system in North America, as it does today. January 2017 S M T W T F S B C D E F G A 1 New Year’s Day 2 3 4 5 6 7 A B C D E F G 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 G A B C D E F Martin Luther 15 16 King, Jr. Day 17 18 19 20 21 F G A B C D E 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 E F G ABCDEFG: December 2016 February 2017 CTA Operations S M T W T F S S M T W T F S Division 1 2 3 1 2 3 4 Group Days Off 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 t Alternate day off if 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 you work on this day 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 29 30 31 l Central offices closed 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 26 27 28 Chicago streetcar #225 is outside of the 77th Street carbarn, sporting an early Chicago Transit Authority emblem but still wearing the red and cream color scheme of its predecessor company, the Chicago Surface Lines. -

Surviving Illinois Railroad Stations

Surviving Illinois Railroad Stations Addison: The passenger depot originally built by the Illinois Central Railroad here still stands. Alden: The passenger depot originally built by the Chicago & North Western Railway here still stands, abandoned. Aledo: The passenger depot originally built by the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad here still stands, used as a community center. Alton: The passenger depot originally built by the Chicago & Alton Railroad here still stands, used as an Amtrak stop. Amboy: The passenger/office and freight stations originally built by the IC here still stand. Arcola: The passenger station originally built by the Illinois Central Railroad here still stands. Arlington Heights: The passenger depot originally built by the C&NW here still stands, used as a Metra stop. Ashkum: The passenger depot originally built by the Illinois Central Railroad here still stands. Avon: The passenger depot originally built by the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad here still stands, used as a museum. Barrington: Two passenger depots originally built by the C&NW here still stand, one used as a restaurant the other as a Metra stop. Bartlett: The passenger depot originally built by the Milwaukee Road here still stands, used as a Metra stop. Batavia: The passenger depot originally built by the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad here still stands, used as a museum. Beardstown: The passenger depot originally built by the CB&Q remains, currently used as MOW building by the BNSF Railway. Beecher: The passenger depot originally built by the Chicago & Eastern Illinois Railroad here still stands. Bellville: The passenger and freight depots originally built by the IC here still stand, both used as businesses. -

Sparks and Cinders

Wisconsin Chapter National Railway Historical Society Volume 67 Number 3 March 2017 Sparks and Cinders Our purpose as members of Wisconsin Chapter—National Railway Historical Society is to gather, preserve and disseminate information, both historic and current, pertaining to railroading in Wisconsin and the Upper Midwest. Visit the Chapter Webpage www.nrhswis.org A Chessie-era eastbound on the C&O pounds the Conrail diamonds at Marion Union Station. John Uckley photo, Brian Schmidt collection In This Issue From the President Blast from the Past 50 Year NRHS Member 1 Upcoming Events March 2017 Northwest Ohio Railroads in the 1970’s TMER&THS (Traction and Bus Club) and 1980’s by Brian Schmidt www.tmer.org Saturday March 18, 2017 - “Name that Slide” Night On Friday March 3rd join Brian Schmidt as he presents Chase Bank - Cudahy 7:30pm “Northwest Ohio Railroads in the 1970’s and 1980’s. Join SE Corner Packard and Layton Use East Lot Brian as he presents railroading in Northwest Ohio and South- east Michigan as seen through the lens of prolific Michigan WISE Division NMRA railfan John Uckley. You will see the big players like Conrail, www.wisedivision.org CSX, Grand Trunk Western and Amtrak. Smaller players De- Bus Trip to Mad City Model Railroad Show - Madison, WI troit and Toledo Shore and Lenawee County in the 1970’s and Saturday February 18, 2017 1980’s. Some of locations that will be seen include some fa- Check webpage for more information vorites like Marion and Toledo, Ohio. Also the lesser known hometown of Uckley Monroe, Michigan. -

Facilities and Exhibits Improvement Survey Online Survey Results Public Input Sessions Results

Facilities and Exhibits Improvement Survey Online Survey Results 940 respondents January 30, 2010 – June 30, 2011 Public Input Sessions Results Seven sessions/118 attendees February 16—March 23, 2010 Prepared by the Virginia Museum of Transportation 303 Norfolk Avenue SW Roanoke, VA 24016 540.342.5670 www.VMT.org September 1, 2011 Virginia Museum of Transportation NS Challenge Survey 1 Virginia Museum of Transportation Facilities and Exhibits Improvement Survey Table of Contents Online survey results Demographics of respondents 3 Questions about exhibit content 4 Questions about history and people 6 Questions about commerce and industry 10 Questions about transportation technology 12 Questions about types of exhibits 14 Additional Comments About scope 18 About facilities and Railyard conditions 20 About rail restoration and rail exhibits 21 About nonrail exhibits 25 About events, activities, and features 26 About excursions, rides, and restoring equipment to operating condition 28 General comments 33 Public input session results Attendee statistics; how to collect stories; stories/content 38 Exhibits/how to tell the stories 41 Programs 43 Facility 45 Guest services 46 Other income; other comments 47 Virginia Museum of Transportation NS Challenge Survey 2 Virginia Museum of Transportation Facilities and Exhibits Improvement Survey January 30, 2010 – June 30, 2011 Online Survey by Survey Monkey, one response allowed per computer Total Started Survey: 940; Total Completed Survey: 806 (85.7%) Survey Demographics: Male: 90.3% Female 9.7% -

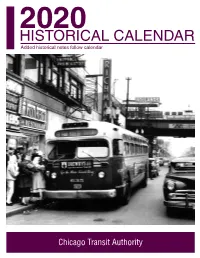

HISTORICAL CALENDAR Added Historical Notes Follow Calendar

2020 HISTORICAL CALENDAR Added historical notes follow calendar Chicago Transit Authority JANUARY 2020 After a snow in December 1951, CTA streetcar #4231 is making its way down Halsted to its terminus at 79th Street. Built in 1948 by the Pullman Company in Chicago, car #4231 was part of a fleet of 600 Presidents Conference Committee (PCC) cars ordered by Chicago Surface Lines (CSL) just before its incorporation into the Chicago Transit Authority. At 48 feet, these were the longest streetcars used in any city. Their comfortable riding experience, along with their characteristic humming sound and color scheme, earned them being nicknamed “Green Hornets” after a well-known radio show of the time. These cars operated on Chicago streets until the end of streetcar service, June 21, 1958. Car #4391, the sole survivor, is preserved at the Illinois Railway Museum in Union, IL. SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT ABCDEFG: December 2019 February 2020 C D E F CTA Operations S M T W T F S S M T W T F S Division 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 Group Days Off 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 t Alternate day off if 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 you work on this day 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 29 30 31 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 l Central offices closed 1 New Year’s Day 2 3 4 F G A B C D E 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 E F G A B C D 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 D E F G A B C Martin Luther 19 20 King, Jr. -

' L^Ca^

RECEIVED 2280 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior JUL 2 7 2007 National Park Service NA1.REGISTER OF HISTORIC" :?•$ ] NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES I PARK SFMVIC'. REGISTRATION FORM 1. NAME OF PROPERTY HISTORIC NAME: ATSF Locomotive No. 2926 OTHER NAME/SITE NUMBER: N/A 2. LOCATION STREET & NUMBER: 1600 Twelfth Street NW (United States General Services Administration) NOT FOR PUBLICATION: N/A CITY OR TOWN: Albuquerque VICINITY: N/A STATE: New Mexico CODE: NM COUNTY: Bernalillo CODE: 01 ZIP CODE: 87125 3. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION_______________________________ As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this _x_nomination __request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _x_meets __does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant __nationally X_statewide,/ _locally. (__See continuation^sheet for additional comments.) Signature of certifying official Date State Historic Preservation Officer State or Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property J£_meets __does not meet the National Register criteria. (__See continuation sheet for additional comments.) ' L^cA^/7 Signature opcommenting or other official Date <^ / State or Federal agency and bureau 4. NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CERTIFICATION I hereby certify that this property is: -, Signature of the Keeper Date of Action entered in the National Register __ See continuation sheet. determined eligible for the National Register __ See continuation sheet. determined not eligible for the National Register removed from the National Register other (explain): __________ USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form ATSF Locomotive No. -

Scale Trains

Celebrating Scale the art of MAGAZINE Trains 1:48 modeling O u July/August 2009 Issue #45 US $6.95 • Can $8.95 Display until August 31, 2009 Celebrating the art of 1:48 modeling Issue #45 Scale July/August 2009 Vol. 8 - No.4 Editor-in-Chief/Publisher Joe Giannovario Trains MAGAZINE [email protected] O Features Art Director Jaini Giannovario [email protected] 4 The Aspen & Western Ry — Red Wittman An On30 layout with many scratchbuilt structures. Managing Editor 12 Chicago March Meet Contest Photos Mike Cougill Part 2 of our contest coverage. [email protected] 15 A New Roundhouse for the Clover Leaf — Warner Clark Building a roundhouse, even to P48 specs, isn’t that difficult. Advertising Manager Jeb Kriigel 21 Greg Heier 1941 - 2009 [email protected] O Scale News editor passes away in April. Customer 23 Detailing Die-Cast Locomotives Part 2 — Joe Giannovario Service Redetailing the tender required the kindness of friends. Spike Beagle 29 Installing Lighted Train Indicators — Charles Morrill Complaints Add this slick detail to your SP and UP locomotives. L’il Bear 31 Modeler’s Trick — Bill Davis CONTRIBUTORS Here’s an inexpensive way to sort and store your strip stock. TED BYRNE GENE CLEMENTS CAREY HINch ROGER C. PARKER 34 Atlas Postwar AAR Boxcar Upgrade — Larry Kline Improve and refine the details of this commonly found model. Subscription Rates: 6 issues 38 A Home Built Rivet Embosser — John Gizzi US - Periodical Class Delivery US$35 US - First Class Delivery (1 year only) US$45 If necessity is the Mother of Invention, then frugality is its Father. -

TRAINLINE Railway Museum Quarterly

railway museum quarterly TRAINLINE Number 3 Published cooperatively by the Tourist Railway Association Winter 2011 and the Association of Railway Museums Twin ex-Toronto PCC cars line up in front of the National Capital Trolley Museum’s new visitor center in Colesville, Maryland. Relocated by freeway construction, NCTM opened its handsome new museum buildings in October 2010 and shortly thereafter hosted ARM’s 2010 Conference. Aaron Isaacs photo Address Service Requested Service Address PERMIT NO. 1096 NO. PERMIT MINNEAPOLIS, MN MINNEAPOLIS, PAID Conyers, GA 30012 GA Conyers, U.S.POSTAGE 1016 Rosser Street Rosser 1016 PRSRT. STD. PRSRT. ARM 2 3 ASSOCIATION OF RAILWAY MUSEUMS TOURIST RAILWAY ASSOCIATION The purpose of the Association of Railway Museums is to The Tourist Railway Association, Inc. is a non-profit lead in the advancement of railway heritage through corporation chartered to foster the development and education and advocacy, guided by the principles set forth in "Recommended Practices for Railway Museums" and operation of tourist railways and museums. incorporated in other best practices generally accepted in the wider museum community. TRAIN Membership ARM Membership Membership is open to all railway museums, tourist Membership in the Association of Railway Museums is open to railroads, excursion operators, private car owners, railroad nonprofit organizations preserving and displaying at least one related publishers, industry suppliers and other interested piece of railway or street railway rolling stock to the public on a persons and organizations. TRAIN, Inc. is the only trade regularly scheduled basis. Other organizations, businesses and association created to represent the broad spectrum of individuals interested in the work of the Association are invited to become affiliates.