BOALT: LEGAL PROFESSION

FIRST AND SECOND CLASSES – ATTORNEY CLIENT RELATIONSHIP & CLIENT IDENTITY

AUGUST 28 & SEPTEMBER 4, 2012

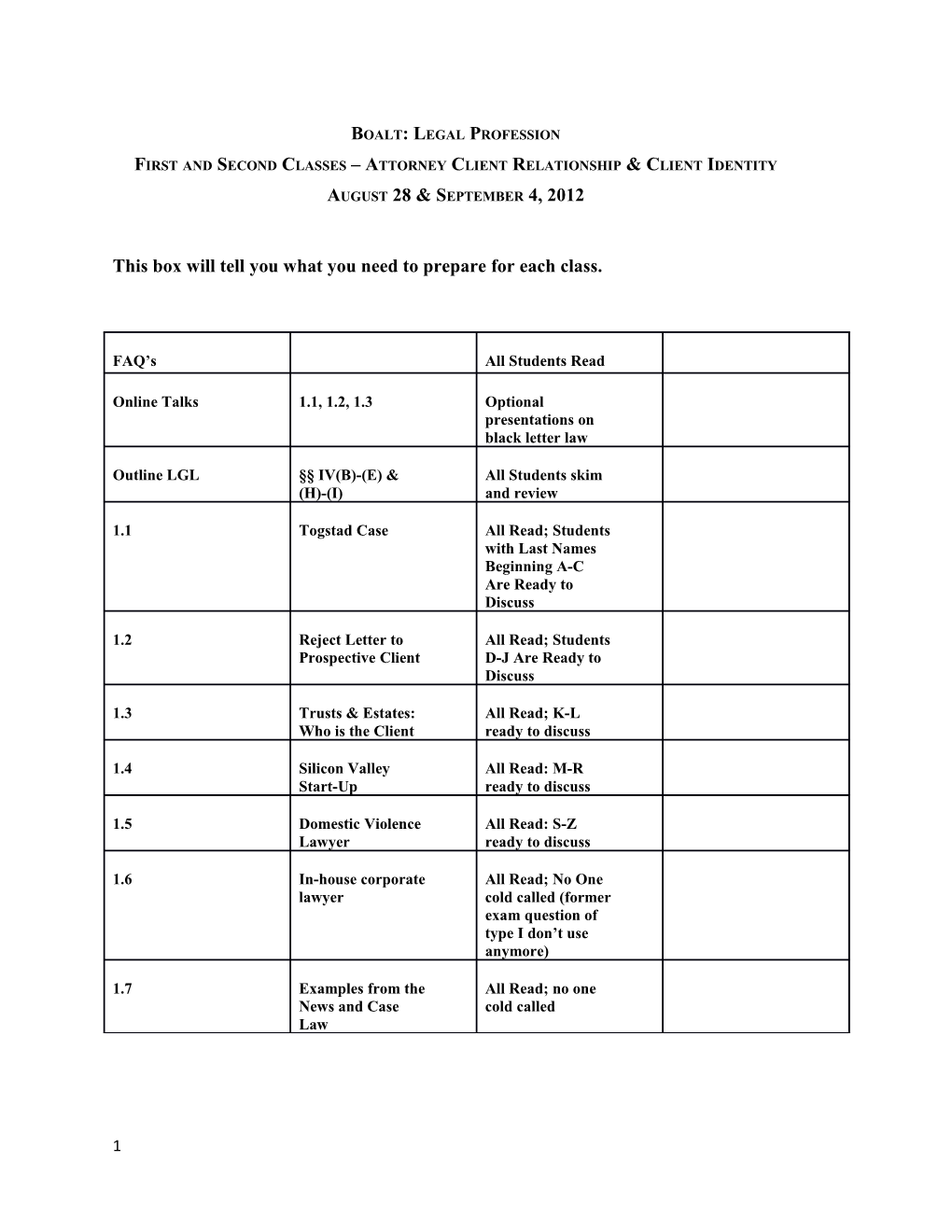

This box will tell you what you need to prepare for each class.

FAQ’s All Students Read

Online Talks 1.1, 1.2, 1.3 Optional presentations on black letter law

Outline LGL §§ IV(B)-(E) & All Students skim (H)-(I) and review

1.1 Togstad Case All Read; Students with Last Names Beginning A-C Are Ready to Discuss

1.2 Reject Letter to All Read; Students Prospective Client D-J Are Ready to Discuss

1.3 Trusts & Estates: All Read; K-L Who is the Client ready to discuss

1.4 Silicon Valley All Read: M-R Start-Up ready to discuss

1.5 Domestic Violence All Read: S-Z Lawyer ready to discuss

1.6 In-house corporate All Read; No One lawyer cold called (former exam question of type I don’t use anymore)

1.7 Examples from the All Read; no one News and Case cold called Law

1 The Attorney Client Relationship Lifecycle (Q&A)

This section is about the attorney client relationship lifecycle. Lawyers’ failure to grasp the basics of that lifecycle is the cause of countless errors, unhappy clients, unhappy attorneys, malpractice suits, and disciplinary actions. Unfortunately, the rules don’t have enough coverage of these issues. Read Scope, Comment [17]; MR 1.18, and whatever rules are mentioned at the start of the examples.

FAQs (Q 1.1) What is an attorney-client relationship (ACR)? (Q 1.2) What kinds of attorney-client relationships are forbidden, permitted, encouraged, or mandatory? (Q 1.3) Do any lawyerly duties arise even before the attorney-client relationship is created? (Q 1.4) What is the legal test for the existence of an ACR? (Q 1.5) What is the effect of the creation of an ACR? (Q 1.6) What are the elements that define any particular ACR? (Q 1.7) When the client is an organization, who or what is the client? (Q 1.8) Is client identity ever an issue when representing natural persons (i.e., human beings)? (Q 1.9) Under what conditions must or may a lawyer terminate an ACR? (Q 1.10) What is the legal test for the end of an ACR? (Q 1.11) What duties do lawyers owe after the termination of the ACR?

QUESTIONS

(Q 1.1) What is an attorney-client relationship (ACR)?

The attorney-client relationship is a fiduciary relationship between a principal (the client) and an agent (the lawyer) in which the lawyer represents the client’s legal interests to some person or some social system (e.g., the courts or the market).

(Q 1.2) What kinds of attorney-client relationships are forbidden, permitted, encouraged, or mandatory?

Some ACRs are forbidden. Lawyers cannot counsel or assist a client in the furtherance of a crime or fraud. (MR 1.2(d)) (On the other hand, an attorney may counsel a client about legal consequences of proposed courses of conduct and about the validity, scope, meaning, and application of the law. MR 1.2(d)) Lawyers cannot commence or continue an ACR that would entail breaches of the rules of professional conduct.

Some ACRs are encouraged. Lawyers should aspire to perform pro bono public service by providing legal representation to those who cannot afford to pay for it. (MR 6.1) Lawyers should aspire to represent the defenseless, the friendless, and the oppressed. (See, Cal. Bus. &

2 Prof. Code § 6068(h); Lawyers Oath (appended to the 1908 Model Code of Professional Conduct))

Some ACRs are mandatory. Courts retain their historical power to appoint lawyers to represent clients. (MR 6.2, 1.16(c)) (Such appointments, however, are rare since the advent of public defender offices.) In some countries other than the USA, the so-called cab-rank rule required a lawyer to represent any paying client. In the USA, lawyers have far more discretion of whom they will represent.

Some ACRs are permitted. If a proposed representation would not further a crime or fraud, and if the objectives of the representation are lawful, the lawyer can exercise her personal discretion about whether she wishes to enter into the ACR. That is, under most circumstances commencing an ACR is at the discretion of both client and lawyer. (Note: there can be significant restrictions on a lawyer’s ability to terminate an ACR.) Under MR 1.2, a lawyer’s decision to enter into an ACR is not to be understood as endorsing the client or the client’s objectives. (However, many people morally judge lawyers by their choice of clients.)

(Q 1.3) Do any lawyerly duties arise even before the attorney client relationship is created?

When meeting with a prospective client about the possibility of entering into an ACR, the duty of confidentiality already applies, as does attorney client privilege. (MR 1.18) Meetings with prospective clients raise ethical risks such as confusion over whether an ACR exists, whether the lawyer already has a conflict adverse to the prospective client, and whether the lawyer will protect the prospective client’s confidences.

(Q 1.4) What is the legal test for the existence of an ACR?

The ethical codes and regulatory statutes say little about the legal test for the creation of the attorney client relationships. We are left to common law approaches. The law could be clearer regarding what, exactly, suffices to create the relationship. Some states use a contract analysis. Some use a tort analysis. Some examine the reasonable expectations of the putative client. Some states ask if the putative client reposed trust and confidence in the lawyer. Here is the test from §14 of the Restatement (Third) Law Governing Lawyers. Notice how it combines a contract test, a tort test, and the notion of judicial appointments.

FORMATION OF ATTORNEY-CLIENT RELATIONSHIP: A

relationship of client and lawyer arises when: (1) a person manifests to a lawyer the person’s intent that the lawyer provide legal services for the person; and either: (a) the lawyer manifests to the person consent to do so; or (b) the lawyer fails to manifest lack of consent to do so, and the lawyer knows or reasonably should know that the person reasonably relies up the lawyer to provide the services; or (2) a tribunal with power to do so appoints the lawyer to provide the services.

3 In some states and under some circumstances, the relationship is required to be memorialized in a written agreement. (See, e.g., Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code §§ 6146-49) But failure to obtain the agreement does not preclude someone from proving that you were his or her lawyer. For purposes of this semester, including the exam, assume that the sole legal test for the existence of an attorney-client relationship is the reasonable expectations of the putative client.

(Q 1.5) What is the effect of the creation of an ACR?

When the ACR is created, fiduciary duties run from the lawyer to the client (e.g., the fiduciary duties of communication, loyalty, competence, confidentiality, diligence, safeguarding the client’s property). The client may have contractual duties to the lawyer, if the lawyer properly contracted for those duties (e.g., fees, liens, etc.). Additionally, the creation of the ACR creates a framework for decision-making authority: the client determines the lawful objectives of the representation, while the attorney determines the means in consultation with the client.

Does that mean that in the discharge of her duties the lawyer owes duties only to the client— that the lawyer can completely disregard the legal rights of third parties? No. Although the lawyer’s fiduciary duties rarely extend beyond clients, the lawyer’s duties to the client are bounded by pre-existing duties such as the duty not to commit fraud on third parties, the duty not to provide false evidence to tribunals, and the duty not to commit crimes. That is, while fulfilling those fiduciary duties to the client, the lawyer also owes duties to the courts, legal system, adversaries, opposing counsel, witnesses, and others. Exactly where to place that boundary between client-duties and social-duties is a highly contested question.

(Q 1.6) What are the elements that define any particular ACR?

You haven’t defined the ACR until you’ve defined (1) who is the client; (2) who is not the client; (3) what is within the scope of the representation; and (4) what is outside the scope of the representation.

The second and fourth elements seem redundant, but experience has shown that they are critical to the proper definition of an ACR.

Lawyers may limit the scope of the representation if the criteria of MR 1.2 are met. There is currently a movement toward permitting unbundled or limited representations, especially in family courts. At the high end of the market, clients are disaggregating the legal work into functional tasks and are assigning each task to a particular service provider. (For example, in a large litigation, the client might have the document review done by non- lawyers in India, the e-discovery done by a specialty boutique, and the bulk of the litigation done by a highly-leveraged, expensive, “big law” firm.

(Q 1.7) When the client is an organization, who or what is the client?

Under the so-called entity theory of representation, when a lawyer forms an ACR with an organization (e.g., corporation or partnership), the client is the entity itself and not the

4 employees or constituents of the entity. (MR 1.13) If the corporation’s attorneys were to undertake to represent any of those constituents, it would be considered an additional representation and one that potentially conflicts with the representation of the organization. Generally, the attorney for the entity will take efforts to ensure that her duty of loyalty is not clouded by any peripheral representations of the entity’s constituents such as directors, officers, shareholders, etc.

Organizations can only act through the acts of the human beings who are the agents, employees, etc., of the entity. Lawyers look to those people for the authorized instructions to carry out for the client. To determine who properly speaks for the entity client, the lawyer looks to the organization’s rules of governance. Note that this rule, 1.13, also governs client identity in the context of representing governmental organizations—a topic of much confusion and controversy.

The entity representation theory seems straight forward, but complications arise. What happens if, for example, a corporate officer trusts and shares confidences with the attorney and the attorney’s advice relates to the personal interests of the officer? Has a new representation ensued? Is there a conflict between the attorney’s representation of the entity and her representation of the officer? And what happens when there is confusion or a dispute over who controls the organization? As the comments to MR 1.13 make clear, these issues often confound even careful lawyers.

Another difficult issue relates to corporate affiliates. For example, if a lawyer represents a parent corporation, does the attorney represent the subsidiaries? Would it be a conflict for that lawyer to represent a third party against the subsidiary? That and related issues will be discussed in the unit on conflicts of interest.

Representation of government entities raises particularly difficult problems. If you are a lawyer employed by the State of Indiana, is your client the agency you work for, the state itself, or even the people of Indiana? (See, MR 1.13, cmt. [7])

When analyzing legal ethics, the very first question often is who is the client? If you want to know the basics of client identity, you should have a basic working knowledge of the law governing representation of (i) competent human beings; (ii) less than fully competent human beings; (iii) publicly held corporations; (iv) smaller, non-public corporations; (v) partnerships; and (vi) government entities.

(Q 1.8) Is client identity ever an issue when representing natural persons (i.e., human beings)?

In the case of natural person clients, client identity can still be an issue, especially where a non-client is paying the legal fees, or where the client is under a disability such as minority, mental illness, or conservatorship. MR 1.14 regulates the representation of clients under a disability.

(Q 1.9) Under what conditions must or may a lawyer terminate an ACR?

5 Lawyers often speak of mandatory withdrawals and permissive withdrawals. Lawyers must seek to terminate ACRs that are unlawful, seek forbidden objectives, or entail ethical breaches. (MR 1.16.) Lawyers may seek to terminate ACRs on a variety of other grounds, such as when there is a breakdown in the ACR relationship or when the client won’t pay the bill. (See MR 1.16.) If the lawyer has made an appearance before a tribunal, termination of the ACR requires the tribunal’s permission and may be denied if, for example, the lawyer seeks to withdraw on the eve of the trial.

(Q 1.10) What is the legal test for the end of an ACR?

For purposes of this semester, assume that the reasonable expectations test governs.

(Q 1.11) What duties do lawyers owe after the termination of the ACR?

Post-ACR, lawyers still owe the duty of confidentiality, and they owe a limited, negative duty of loyalty tied to the subject matter of the terminated representation. That is, the lawyer cannot take on matters adverse to former clients if the matters are the same or substantially related as the matter the lawyer formerly handled for the former client. (MR 1.9) There may be additional limitations on a lawyer’s ability to attack the work product of his prior representation. Additionally, lawyers must return the client file, papers, property, and any unearned fees and also must assist in the transfer of the matter to new counsel.

1.1: Togstad v. Vesely, Otto, Miller & Keefe

Read this case and consider whether or not an attorney-client relationship was created. Do the client and attorney have different understandings of what was being said? If so, why? While the appellate court’s legal analysis is important, please try to see the fact pattern through the eyes of the client and then through the eyes of the lawyer. John R. Togstad, et al., Respondents, v. Vesely, Otto, Miller & Keefe and Jerre Miller, Appellants

Supreme Court of Minnesota

291 N.W.2d 686; 1980 Minn. LEXIS 1373

OPINIONBY: PER CURIAM

OPINION: This is an appeal by the defendants from a judgment of the Hennepin County District Court involving an action for legal malpractice. The jury found that the defendant attorney Jerre Miller was negligent and that, as a direct result of such negligence, plaintiff John Togstad sustained damages in the amount of $610,500 and his wife, plaintiff Joan Togstad, in the amount of $39,000. Defendants (Miller and his law firm) appeal to this court from the denial of their motion for judgment notwithstanding the verdict or, alternatively, for a new trial. We affirm.

6 In August 1971, John Togstad began to experience severe headaches and on August 16, 1971, was admitted to Methodist Hospital where tests disclosed that the headaches were caused by a large aneurism on the left internal carotid artery. The attending physician, Dr. Paul Blake, a neurological surgeon, treated the problem by applying a Selverstone clamp to the left common carotid artery. The clamp was surgically implanted on August 27, 1971, in Togstad's neck to allow the gradual closure of the artery over a period of days.

The treatment was designed to eventually cut off the blood supply through the artery and thus relieve the pressure on the aneurism, allowing the aneurism to heal. It was anticipated that other arteries, as well as the brain's collateral or cross-arterial system would supply the required blood to the portion of the brain which would ordinarily have been provided by the left carotid artery. The greatest risk associated with this procedure is that the patient may become paralyzed if the brain does not receive an adequate flow of blood. In the event the supply of blood becomes so low as to endanger the health of the patient, the adjustable clamp can be opened to establish the proper blood circulation.

In the early morning hours of August 29, 1971, a nurse observed that Togstad was unable to speak or move. At the time, the clamp was one-half (50%) closed. Upon discovering Togstad's condition, the nurse called a resident physician, who did not adjust the clamp. Dr. Blake was also immediately informed of Togstad's condition and arrived about an hour later, at which time he opened the clamp. Togstad is now severely paralyzed in his right arm and leg, and is unable to speak.

About 14 months after her husband's hospitalization began, plaintiff Joan Togstad met with attorney Jerre Miller regarding her husband's condition. Neither she nor her husband was personally acquainted with Miller or his law firm prior to that time. John Togstad's former work supervisor, Ted Bucholz, made the appointment and accompanied Mrs. Togstad to Miller's office. Bucholz was present when Mrs. Togstad and Miller discussed the case.

Mrs. Togstad had become suspicious of the circumstances surrounding her husband's tragic condition due to the conduct and statements of the hospital nurses shortly after the paralysis occurred. One nurse told Mrs. Togstad that she had checked Mr. Togstad at 2 a.m. and he was fine; that when she returned at 3 a.m., by mistake, to give him someone else's medication, he was unable to move or speak; and that if she hadn't accidentally entered the room no one would have discovered his condition until morning. Mrs. Togstad also noticed that the other nurses were upset and crying, and that Mr. Togstad's condition was a topic of conversation.

Mrs. Togstad testified that she told Miller "everything that happened at the hospital," including the nurses' statements and conduct which had raised a question in her mind. She stated that she "believed" she had told Miller "about the procedure and what was undertaken, what was done, and what happened." She brought no records with her. Miller took notes and asked questions during the meeting, which lasted 45 minutes to an hour. At its conclusion, according to Mrs. Togstad, Miller said that "he did not think we had a legal case, however, he was going to discuss this with his partner." She understood that if Miller changed his mind after talking to his partner, he would call her. Mrs. Togstad "gave it" a few days and, since she did not hear from Miller, decided "that they had come to the

7 conclusion that there wasn't a case." No fee arrangements were discussed, no medical authorizations were requested, nor was Mrs. Togstad billed for the interview.

Mrs. Togstad denied that Miller had told her his firm did not have expertise in the medical malpractice field, urged her to see another attorney, or related to her that the statute of limitations for medical malpractice actions was two years. She did not consult another attorney until one year after she talked to Miller. Mrs. Togstad indicated that she did not confer with another attorney earlier because of her reliance on Miller's "legal advice" that they "did not have a case."

On cross-examination, Mrs. Togstad was asked whether she went to Miller's office "to see if he would take the case of [her] husband * * *." She replied, "Well, I guess it was to go for legal advice, what to do, where shall we go from here? That is what we went for." Again in response to defense counsel's questions, Mrs. Togstad testified as follows:

Q: And it was clear to you, was it not, that what was taking place was a preliminary discussion between a prospective client and lawyer as to whether or not they wanted to enter into an attorney-client relationship? A: I am not sure how to answer that. It was for legal advice as to what to do. Q: And Mr. Miller was discussing with you your problem and indicating whether he, as a lawyer, wished to take the case, isn't that true? A: Yes.

On re-direct examination, Mrs. Togstad acknowledged that when she left Miller's office she understood that she had been given a "qualified, quality legal opinion that [she and her husband] did not have a malpractice case."

Miller's testimony was different in some respects from that of Mrs. Togstad. Like Mrs. Togstad, Miller testified that Mr. Bucholz arranged and was present at the meeting, which lasted about 45 minutes. According to Miller, Mrs. Togstad described the hospital incident, including the conduct of the nurses. He asked her questions, to which she responded. Miller testified that "the only thing I told her [Mrs. Togstad] after we had pretty much finished the conversation was that there was nothing related in her factual circumstances that told me that she had a case that our firm would be interested in undertaking."

Miller also claimed he related to Mrs. Togstad "that because of the grievous nature of the injuries sustained by her husband, that this was only my opinion and she was encouraged to ask another attorney if she wished for another opinion" and "she ought to do so promptly." He testified that he informed Mrs. Togstad that his firm "was not engaged as experts" in the area of medical malpractice, and that they associated with the Charles Hvass firm in cases of that nature. Miller stated that at the end of the conference he told Mrs. Togstad that he would consult with Charles Hvass and if Hvass's opinion differed from his, Miller would so inform her. Miller recollected that he called Hvass a "couple days" later and discussed the case with him. It was Miller's impression that Hvass thought

8 there was no liability for malpractice in the case. Consequently, Miller did not communicate with Mrs. Togstad further.

On cross-examination, Miller testified as follows: Q: Now, so there is no misunderstanding, and I am reading from your deposition, you understood that she was consulting with you as a lawyer, isn't that correct? A: That's correct. Q: That she was seeking legal advice from a professional attorney licensed to practice in this state and in this community? A: I think you and I did have another interpretation or use of the term "Advice". She was there to see whether or not she had a case and whether the firm would accept it. Q: We have two aspects; number one, your legal opinion concerning liability of a case for malpractice; number two, whether there was or wasn't liability, whether you would accept it, your firm, two separate elements, right? A: I would say so. Q: Were you asked on page 6 in the deposition, folio 14, "And you understood that she was seeking legal advice at the time that she was in your office, that is correct also, isn't it?" And did you give this answer, "I don't want to engage in semantics with you, but my impression was that she and Mr. Bucholz were asking my opinion after having related the incident that I referred to." The next question, "Your legal opinion?" Your answer, "Yes." Were those questions asked and were they given? MR. COLLINS: Objection to this, Your Honor. It is not impeachment. THE COURT: Overruled. THE WITNESS: Yes, I gave those answers. Certainly, she was seeking my opinion as an attorney in the sense of whether or not there was a case that the firm would be interested in undertaking.

Kenneth Green, a Minneapolis attorney, was called as an expert by plaintiffs. He stated that in rendering legal advice regarding a claim of medical malpractice, the minimum an attorney should do would be to request medical authorizations from the client, review the hospital records, and consult with an expert in the field. John McNulty, a Minneapolis attorney, and Charles Hvass testified as experts on behalf of the defendants. McNulty stated that when an attorney is consulted as to whether he will take a case, the lawyer's only responsibility in refusing it is to so inform the party. He testified, however, that when a lawyer is asked his legal opinion on the merits of a medical malpractice claim, community standards require that the attorney check hospital records and consult with an expert before rendering his opinion.

Hvass stated that he had no recollection of Miller's calling him in October 1972 relative to the Togstad matter. He testified that: A * * * when a person comes in to me about a medical malpractice action, based upon what the individual has told me, I have to make a

9 decision as to whether or not there probably is or probably is not, based upon that information, medical malpractice. And if, in my judgment, based upon what the client has told me, there is not medical malpractice, I will so inform the client. Hvass stated, however, that he would never render a "categorical" opinion. In addition, Hvass acknowledged that if he were consulted for a "legal opinion" regarding medical malpractice and 14 months had expired since the incident in question, "ordinary care and diligence" would require him to inform the party of the two-year statute of limitations applicable to that type of action.

This case was submitted to the jury by way of a special verdict form. The jury found that Dr. Blake and the hospital were negligent and that Dr. Blake's negligence (but not the hospital's) was a direct cause of the injuries sustained by John Togstad; that there was an attorney-client contractual relationship between Mrs. Togstad and Miller; that Miller was negligent in rendering advice regarding the possible claims of Mr. and Mrs. Togstad; that, but for Miller's negligence, plaintiffs would have been successful in the prosecution of a legal action against Dr. Blake; and that neither Mr. nor Mrs. Togstad was negligent in pursuing their claims against Dr. Blake. The jury awarded damages to Mr. Togstad of $610,500 and to Mrs. Togstad of $39,000.

On appeal, defendants raise the following issues:

(1) Did the trial court err in denying defendants' motion for judgment notwithstanding the jury verdict?

(2) Does the evidence reasonably support the jury's award of damages to Mrs. Togstad in the amount of $39,000?

(3) Should plaintiffs' damages be reduced by the amount of attorney fees they would have paid had Miller successfully prosecuted the action against Dr. Blake?

(4) Were certain comments of plaintiffs' counsel to the jury improper and, if so, were defendants entitled to a new trial?

In a legal malpractice action of the type involved here, four elements must be shown: (1) that an attorney-client relationship existed; (2) that defendant acted negligently or in breach of contract; (3) that such acts were the proximate cause of the plaintiffs' damages; (4) that but for defendant's conduct the plaintiffs would have been successful in the prosecution of their medical malpractice claim. See, Christy v. Saliterman, 288 Minn. 144, 179 N.W.2d 288 (1970).

This court first dealt with the element of lawyer-client relationship in the decision of Ryan v. Long, 35 Minn. 394, 29 N.W. 51 (1886). The Ryan case involved a claim of legal malpractice and on appeal it was argued that no attorney-client relation existed. This court, without stating whether its conclusion was based on contract principles or a tort theory, disagreed:

10 It sufficiently appears that plaintiff, for himself, called upon defendant, as an attorney at law, for "legal advice," and that defendant assumed to give him a professional opinion in reference to the matter as to which plaintiff consulted him. Upon this state of facts the defendant must be taken to have acted as plaintiff's legal adviser, at plaintiff's request, and so as to establish between them the relation of attorney and client. Id. (citation omitted). More recent opinions of this court, although not involving a detailed discussion, have analyzed the attorney-client consideration in contractual terms. See, Ronnigen v. Hertogs, 294 Minn. 7, 199 N.W.2d 420 (1972); Christy v. Saliterman, supra. For example, the Ronnigen court, in affirming a directed verdict for the defendant attorney, reasoned that "under the fundamental rules applicable to contracts of employment * * * the evidence would not sustain a finding that defendant either expressly or impliedly promised or agreed to represent plaintiff * * *." 294

Minn. at 11, 199 N.W.2d at 422. The trial court here, in apparent reliance upon the contract approach utilized in Ronnigen and Christy, supra, applied a contract analysis in ruling on the attorney-client relationship question. This has prompted a discussion by the Minnesota Law Review, wherein it is suggested that the more appropriate mode of analysis, at least in this case, would be to apply principles of negligence, i.e., whether defendant owed plaintiffs a duty to act with due care. 63 Minn. L. Rev. 751 (1979).

We believe it is unnecessary to decide whether a tort or contract theory is preferable for resolving the attorney-client relationship question raised by this appeal. The tort and contract analyses are very similar in a case such as the instant one, and we conclude that under either theory the evidence shows that a lawyer-client relationship is present here. The thrust of Mrs. Togstad's testimony is that she went to Miller for legal advice, was told there wasn't a case, and relied upon this advice in failing to pursue the claim for medical malpractice. In addition, according to Mrs. Togstad, Miller did not qualify his legal opinion by urging her to seek advice from another attorney, nor did Miller inform her that he lacked expertise in the medical malpractice area. Assuming this testimony is true, as this court must do, see, Cofran v. Swanman,

225 Minn. 40, 29 N.W.2d 448 (1947), we believe a jury could properly find that Mrs. Togstad sought and received legal advice from Miller under circumstances which made it reasonably foreseeable to Miller that Mrs. Togstad would be injured if the advice were negligently given. Thus, under either a tort or contract analysis, there is sufficient evidence in the record to support the existence of an attorney-client relationship.

Affirmed.

1.2. Example: Reject Letters to Prospective Client Following are two letters a plaintiffs legal malpractice attorney sends when he decides not to take on a matter for a prospective client. Analyze and evaluate the letters sentence-by-sentence and paragraph-by- paragraph.

11 CERTIFIED MAIL - RETURN RECEIPT REQUESTED

Name Address

Re: Possible Legal Malpractice Claim

Dear :

Based upon your telephone conference of [enter date] with my Legal Assistant [or reference correspondence if letter sent], and upon careful consideration of your claim, this is to advise you that I cannot proceed with your malpractice claim.

While this decision is final on my part, it may well be that another attorney can represent you. My decision is not and should not be construed by you to be an opinion as to the merits of your case. I advise you to contact other legal counsel at once.

You have only one year from the date you learned of or should have learned of an alleged act of legal malpractice within which to commence an action against the parties responsible for the loss. There are also additional complex requirements which must be met in a timely fashion. Failure to meet these requirements will forever bar you from your claim against the responsible parties.

There are certain circumstances which may extend the Statute of Limitations, or possibly restrict the time in which you must file a claim. I do not have sufficient information to render an opinion as to whether any of these circumstances apply in your case.

You may wish to recontact [referring attorney/source], the attorney/person who referred you to my office, or utilize the Lawyer Referral Service of the Santa Clara County (or county where they reside) Bar Association to obtain a reference

Thank you for your trust and confidence. I regret that I cannot be of service to

Very truly yours,

cc: Referring Attorney/Source

* * * * *

12 Date

Attorney Name Firm Address City

Re: CLAIMS OF (name of person contacting your office) FOR LEGAL MALPRACTICE

Dear Attorney/Source:

Thank you for referring [person seeking attorney services] to my office. At this time it is not feasible for me to proceed further with his/her case.

I have enclosed a copy of the letter I have sent to him/her for your review.

I deeply appreciate the trust and confidence you have placed in me by referring [person seeking attorney services]. If there is any way I can be of service to you or your firm in the future, please do not hesitate to call.

Very truly yours,

LAW OFFICES OF

Enclosure

Hard Drive: Desktop Folder: Claim Letter

1.3: Example: Trusts & Estates: Who is the Client

This example is based upon a hypothetical discussed in Thomas L. Shaffer, “The Legal Ethics of Radical Individualism,” 65 Tex. L. Rev. 963 (1987). In that article, Professor Shaffer argues that the standard answer to the question “Who is the client?” may sometimes be an ethical evasion. How would you define the client in The Case of the Unwanted Will‖? Do you favor Shaffer’s approach? Assuming that the ethics rules do indeed assume a radical individuality, is there anything to say for or against that assumption? We’ll start with the hypothetical and move to Shaffer’s article.

* * * * *

13 A married couple, Miriam and Henry, visit Colleen O’Hara, a trusts and estates lawyer, to finalize and sign a will that will leave their estate in equal shares to their three children. Miriam walks from the conference room to the kitchen to get some coffee and bumps into O’Hara, who is busy pulling the final papers together.

“I bet it’ll feel good to get your will finalized,” said O’Hara.

“That will is mostly Henry’s idea, but I’ll be glad to get this signed,” said Miriam.

“What do you mean?”

“My niece, my late sister’s daughter, lived with us practically as our own child. I would have left her some money. But, Henry feels so strongly about it.”

* * * * *

Thomas L. Shaffer:

Most of what American lawyers and law teachers call legal ethics is not ethics. Most of what is called legal ethics is similar to rules made by administrative agencies. It is regulatory. Its appeal is not to conscience, but to sanction. It seeks mandate rather than insight. I argue here that what remains and appropriately is called ethics has been distorted by the weaker side of an old issue in academic moral philosophy. This "weaker side" rests on two doctrines: first, that fact and value are separate; and second, that the moral agent acts alone; as W.H. Auden put it, each of us is alone on a moral planet tamed by terror. The influence of this philosophical position deprives legal ethics of truthfulness and of depth. As a principal example of the distortion, I use the case of lawyers employed by and for families, and by and for associations that use the metaphor of family to describe themselves.

I. The Ethical Context

Ethics properly defined is thinking about morals. It is an intellectual activity and an appropriate academic discipline, but it is valid only to the extent that it truthfully describes what is going on. Those in contemporary ethics who concentrate on the importance of the truthful account argue first that fact and value are not separate—that stating the facts is, as Iris Murdoch put it, a moral act, a moral skill, and a moral art; and second, that organic communities of persons are prior in life and in culture to individuals—in other words, that the moral agent is not alone.

14 In the practice of estate planning, for example, the facts that are available for moral description are death and property: property seen in the context of mortality, death seen in the context of owning things.

* * * * *

This principled analysis of The Case of the Unwanted Will fails because of what is prior to analysis: the moral art of description. The failure is sad and, I think, corrupting. It is corrupting, first, because it rests on an untruthful account of what is going on. What is present in the law office is a family, and this one-lawyer-for-each-person way of first seeing a moral quandary in this situation and then resolving the quandary with the ethics of autonomy (the ethics of aloneness) leaves the family out of the account. The analysis looks on [Miriam] as a collection of interests and rights that begin and end in radical individuality. Her affiliation with her husband, and with the children they have made and reared, is seen as a product of individuality(!), of contract and consent, of promises and the keeping of promises—all the consensual connections that lonely individuals use when they want circumstantial harmony. The employment of the lawyer is a result, then, of the links, the promises, the contract, the consent, and the need for circumstantial harmony. The family in the office is there only as the product of promise and consent. It is relevant to the legal business at hand only because the (radical) individuals, each in momentary and circumstantial harmony with one another, want it to be. The promise and the consent create the family.

This description is offered by the legal ethics of radical individualism. It is sad, corrupting, and untruthful. An alternative argument is that the family created the promises, the contract, the consent, and the circumstantial harmony—not the other way around. The family is not the harmony; it is where the harmony (and disharmony) comes from. A truthful description of The Case of the Unwanted Will is that the lawyer's employer is a family. I suspect that that proposition will sound unusual in legal ethics, but my argument would be ordinary in other contexts. It treats, sees, and describes the family the way families are treated, seen, and described in the stories we tell, in the television commercials we watch, in the comics, and in our religious tradition. In these ordinary ways of accounting to ourselves for ourselves, it is the family that causes individuals to make the promises that begin, develop, and continue families. The family causes people to seek human harmonies and, consequently, to create more families, as well as associations such as businesses, clubs, and professions, that account for themselves with family metaphors.

Organic communities such as families are prior to individuals. The lawyer in The Case of the Unwanted Will, for example, did not err in turning his attention to [Miriam], in [Henry’s] absence. (Nor would it have been a mistake to turn his attention to [Henry], in [Miriam’s] absence; if evenhandedness is important, it would have been more evenhanded to talk privately with each of them.) The deep things to be found out about [them], in particular the deep things

15 involved in their will making, are family things. Inquiring into deep family things is not only tolerated, but it is required by common representation, because the client is the family. Any other description is incomplete and, thus, untruthful and corrupting. If an adequate account of what is going on in the family (to the extent that it has to do with their will making) requires talking to either or both parents alone, then talking to them alone is appropriate. If the family is well represented, it (that is, each person in it) will learn how to take [Miriam’s] purposes into account, because [Miriam] is in the family.

1.4: Example: Silicon Valley Start-Up

A venture capitalist that your firm has often represented sends your firm a new client. It’s a small, five-shareholder technology corporation that wants to reincorporate itself in Delaware, to draft a series of employment agreements for the founders (i.e., the five shareholders), and to handle an influx of financing from a different set of venture capitalists (i.e., a second round financing). The second round VCs will invest $15 million and will want to have the rights to manage the business as they see fit. Each founder needs an employee agreement that governs their compensation, stock ownership rights, and what will happen to those shares if the employee leaves the company voluntarily or involuntarily. You know that corporate start-ups cannot afford to have large shareholders leave the company and keep their shares. You also know that the founders have sunk years of their lives into the start-up and don’t want to be tossed out on the street by the new VCs.

One of the founders sends you this email message:

I’ve seen the latest drafts of the Employment Agreements. Can you break it down for me? What do I get if I leave the company on my own accord? What do I get if I get fired over my objection?

How should you respond?

1.5: Example: Domestic Violence Lawyer

You work at a non-profit legal clinic for victims of domestic violence (the Domestic Abuse Advocates). It’s the second Tuesday of the month, so you are at a table at a local community center along with two associates of local law firms, fielding drop-in questions. One woman, a former client, has brought her friend, Doris, to talk to you. This is the third time that Doris has made a drop-in visit. With each prior visit, Doris has come closer and closer to initiating a protective order proceeding against her husband, but her social and religious beliefs make her reluctant to do so. Tonight she has questions about what the timetable for litigation is generally like, whether the local judges are friendly or mean, and whether court proceedings are open to the public.

16 Another visitor, Maria, has questions because she has been accused of battering her domestic partner, the woman she has been living with for many years. Another visitor, Susan, comes with her mother and has questions about how to divorce her abusive husband. Susan is worried about the tax and financial implications of divorce.

Be prepared to speak to Doris, Maria and Susan about the attorney-client relationship issues raised by these encounters.

1.6: In-House Corporate Lawyer (Prior Exam Question)

You are General Counsel at The Parts Supply, an automotive and trucking parts company. You often meet with Mike Morris, the Midwest Regional Vice President, who in addition to running legal issues by you, chats with you about everything from the weather, the local schools, and Hoosier basketball. In June 2002, Morris walked into your office, slumped down in a chair and nervously lit up a cigarette—a habit you’d thought he’d kicked. He asked if taking a government purchaser out on hunting trips would be considered commercial bribery. You said that anything of value can be a bribe. He asked about the jail time a briber might serve. You told him that bribery can cost five years in prison. He asked if it mattered that he began his hunting trips with the purchaser when they were in high school together. You told Morris you couldn’t give good advice if he dripped out the facts one by one. You asked Morris to trust you with the whole story. Here’s what he said.

“Jason Spencer, my old high school buddy, works for the City and County of St. Louis purchasing car and truck parts for the various municipal fleets. I took Spencer on several hunting trips over the past year. My treat. Spencer never paid. Sometimes we just drove out to the country, but sometimes we’d stay at upscale hunting or fishing lodges.

“Back in May, Spencer signed a policy allowing the County to purchase parts that aren’t certified by the National Automotive Parts Laboratory. NAPL is a national testing agency, and most everyone requires NAPL certified parts. Spencer also signed a technical specification permitting County trucks to be outfitted with smaller, less powerful brake assemblies. I had lobbied Spencer for both changes, because The Parts Supply carries the non-certified, smaller brake assemblies. They are cheaper for the County, and we are glad to sell them. Spencer and I briefly discussed the changes during one of our hunting trips.

“In late May, the County published a Request For Bids on a large contract for a variety of parts, including quite a few brake assemblies. Because prices on the other parts are largely uniform, The Parts Supply used its price advantage with the non-certified parts to make a great bid. We won the Request. We already shipped some parts, and will make additional deliveries over the next two years.

17 “ Just before the final bids were submitted, the manufacturer of the brake assemblies called about some safety concerns. Ten brake failures have been reported nationwide. He said that no recall was currently contemplated because it seemed that the assemblies had failed only when they were installed on trucks that were too large for the parts. He wanted me to report any potential problems.

“Well, bad things are happening. A County truck plowed through a storefront last week. We don’t yet know what caused the accident, but I think his truck had the small brake assembly. I just heard one hour ago that another County truck crashed at the bottom of a downgrade. I don’t want to call Spencer or the manufacturer and highlight the problem.

“Yesterday, I saw one of my competitors at a hunting goods store. He asked me, ‘Hey, Morris, are you buying more goodies for your pal, Spencer?’ That’s why I’m talking to you. Look, Spencer’s cost-saving policies are perfectly justified. But if people find out about what’s happened, everyone will think the worst and I’m going to jail for five years—or worse if people are killed.”

You told Morris that you need to begin a thorough investigation and that you need to talk to others at the company. Morris screamed at you. He said that you can’t tell anyone about the facts. He said that you are his attorney, and that he is trusting you.

Is there an attorney-client relationship between you and Morris? What consequences flow from this determination?

1.7: Examples from the News and Case Law (A) News accounts have covered the criminal prosecution of George Zimmerman for the homicide of Trayvon Martin. Below are excerpts from the state’s prosecutor’s press conference following the initiation of the criminal proceedings against Zimmerman.

ANGELA COREY, FLORIDA STATE ATTORNEY: Good evening, everyone. I am Angela Corey, the special prosecutor for the Trayvon Martin case.

Just moments ago, we spoke by phone with Sybrina Fulton and Tracy Martin. It was less than three weeks ago that we told those sweet parents that we would get answers to all of their questions no matter where our quest for the truth led us.

When they appointed us to this case less than three weeks ago, I want you to know that these two fine prosecutors, despite all that is on their plate already, handling all of the homicides in the Fourth Judicial Circuit, supervising the other young lawyers who also handle homicides, they willingly took this case on and said, we will lead this effort to seek justice for Trayvon.

The Supreme Court has defined our role on numerous occasions as prosecutors that we are not only ministers of justice; we are seekers of the truth. And we stay true to that mission. Again, we

18 prosecute on facts and the laws of the great and sovereign state of Florida, and that's the way it will be in this case.

We thank all of the people across this country who have sent positive energy and prayers our way. We ask you to continue to pray for Trayvon's family, as well as for our prosecution team.

QUESTION: (OFF-MIKE)

COREY: I am going to be quite honest with you. And I have some people who have lived through our justice system here. And they are among the finest people in Jacksonville, Florida. They represent but a small sample of the people who know that those of us in law enforcement are committed to justice for every race, every gender, every person of any persuasion whatsoever.

They are our victims. We only know one category as prosecutors, and that's a V. It is not a B, it is not a W, it is not an H. It is V for victim. That's who we work tirelessly for. And that's all we know, is justice for our victims. And we still have to maintain the constitutional rights. Remember our role, ministers of justice.

QUESTION: Can you shed any more light on (OFF-MIKE)

COREY: I think that after meeting with Trayvon's parents that first Monday night after we got appointed in this case -- Bernie was there, John was there, our prosecution team was there. The first thing we did was pray with them. We opened our meeting in prayer.

Mr. Crump and Mr. Parks were there. We did not promise them anything. In fact, we specifically talked about if criminal charges do not come out of this, what can we help you do to make sure your son's death is not in vain?

And they were very kind and very receptive to that. And as I stated, Mr. de la Roinda has been in touch with Mr. Crump and with Ms. Fulton and Mr. Martin since we took over this case. And we intend to stay in touch with them.

(B) One of the many collapses of alleged Ponzi schemes was Stanford Financial, which was represented by the Proskauer firm. The SEC took testimony under oath from one of Stanford Financial’s officers, who was accompanied at the deposition by a lawyer from Proskauer. At the start of the deposition, the SEC asked on the record if the lawyer represented the witness, and this is what the lawyer said:

"I represent her insofar as she is an officer or director of one of the Stanford affiliated companies."

(C) The general counsel of PSU was NAME, and when certain employees of PSU gave grand jury testimony and were asked if they were represented by counsel. Here’s a news account of what transpired.1

Three top Penn State University administrators were each posed a question from prosecutors when they testified separately last year before the grand jury investigating Jerry Sandusky:

1 Centre Daily Times (http://www.centredaily.com/2012/07/27/3274899/baldwins-role-in-scandal- questioned.html)( July 27, 2012 )

19 Do you have counsel with you today?

Then-university president Graham B. Spanier, athletic director Tim Curley, and vice president Gary Schultz each offered the same answer: Yes, Cynthia Baldwin, the university’s general counsel.

But Baldwin has since maintained that she represented none of them and instead sat in on the proceedings on behalf of the university.

(D) Under the terms of a technology license, the licensee assumed all control over prosecution of patents on the technology. In prosecuting the patents, the licensee’s lawyers had numerous conversations with the inventors and other personnel of the licensor. Later, when an ownership dispute arose between the licensor, the inventors, and the licensees, all three asserted that they were represented by the same lawyer (who thought she represented only the licensee).

20