Econ 522 – Lecture 18 (Nov 8 2007)

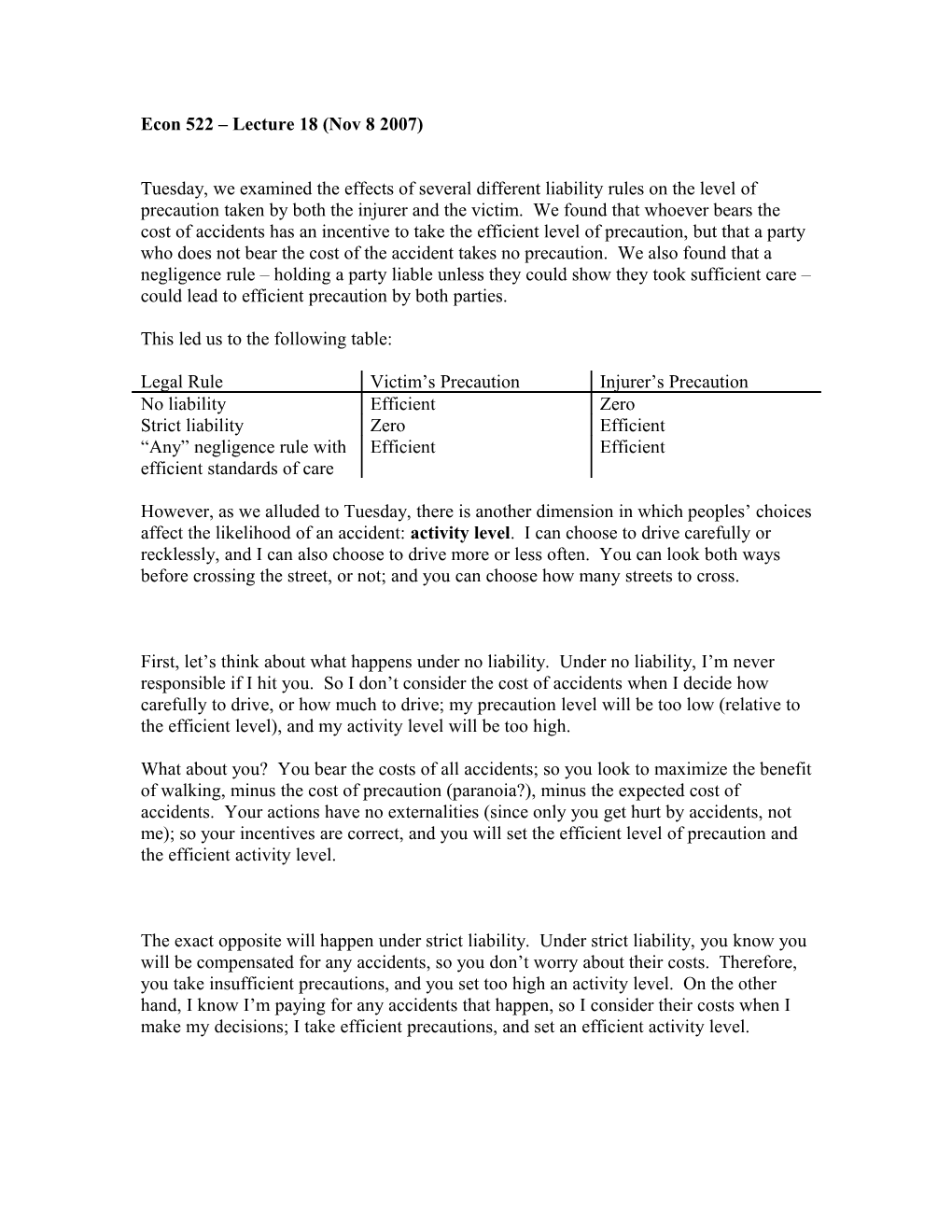

Tuesday, we examined the effects of several different liability rules on the level of precaution taken by both the injurer and the victim. We found that whoever bears the cost of accidents has an incentive to take the efficient level of precaution, but that a party who does not bear the cost of the accident takes no precaution. We also found that a negligence rule – holding a party liable unless they could show they took sufficient care – could lead to efficient precaution by both parties.

This led us to the following table:

Legal Rule Victim’s Precaution Injurer’s Precaution No liability Efficient Zero Strict liability Zero Efficient “Any” negligence rule with Efficient Efficient efficient standards of care

However, as we alluded to Tuesday, there is another dimension in which peoples’ choices affect the likelihood of an accident: activity level. I can choose to drive carefully or recklessly, and I can also choose to drive more or less often. You can look both ways before crossing the street, or not; and you can choose how many streets to cross.

First, let’s think about what happens under no liability. Under no liability, I’m never responsible if I hit you. So I don’t consider the cost of accidents when I decide how carefully to drive, or how much to drive; my precaution level will be too low (relative to the efficient level), and my activity level will be too high.

What about you? You bear the costs of all accidents; so you look to maximize the benefit of walking, minus the cost of precaution (paranoia?), minus the expected cost of accidents. Your actions have no externalities (since only you get hurt by accidents, not me); so your incentives are correct, and you will set the efficient level of precaution and the efficient activity level.

The exact opposite will happen under strict liability. Under strict liability, you know you will be compensated for any accidents, so you don’t worry about their costs. Therefore, you take insufficient precautions, and you set too high an activity level. On the other hand, I know I’m paying for any accidents that happen, so I consider their costs when I make my decisions; I take efficient precautions, and set an efficient activity level. What happens under a negligence rule? First, consider simple negligence. I know I won’t be liable as long as I take sufficient care; so under a simple negligence rule, I’ll take efficient precaution. But once I’m doing that, I don’t have to worry about the cost of accidents, since I’m not going to owe any damages; so I don’t consider the cost of accidents when I choose my activity level, and therefore I set it too high. Under a simple negligence rule, I’ll drive carefully, but I’ll still drive too much.

As for you, you know I’ll be driving carefully, so you know that you’ll still be incurring the costs of any accidents that occur; so you set both your precaution level and your activity level efficiently.

The same will be true for a rule of simple negligence with a defense of contributory negligence, or a rule of comparative negligence. We know that both these rules lead to efficient precaution; but as long as we’re both taking efficient precaution, I’m still not liable for damages. So you still bear the “residual risk” of accidents, and I don’t; so you set your activity level efficiently, and I set mine too high. Once again, under any of these rules, I drive carefully; but since I’m driving carefully, I know I won’t be liable for accidents, so I choose to drive too much.

Finally, what happens under a strict liability rule with a defense of contributory negligence? Here, I’m liable for damages unless I can show you were negligent. We know that this will lead you to take efficient precaution; which means I expect to be held liable for any damages that occur. Thus, I internalize their cost, and set both my precaution level and my activity level efficiently. On the other hand, since you’re being careful, you know that you won’t bear the cost of accidents; so you ignore their cost, and set your activity level too high.

Legal Rule Victim Injurer Victim Injurer Precaution Precaution Activity Activity No liability Efficient Zero Efficient Too High Strict liability Zero Efficient Too High Efficient Simple Neg Efficient Efficient Efficient Too High Simple Neg, Efficient Efficient Efficient Too High Contrib Neg Comparative Efficient Efficient Efficient Too High Neg Strict Liab, Efficient Efficient Too High Efficient Contrib Neg Which rule is the most efficient, then, depends on the situation. That is, it depends on whose choices have the bigger impact.

In situations with unilateral precaution – situations where only one party needs to take steps to avoid accidents – no liability or strict liability work perfectly well. In situation with bilateral precaution, negligence rules give appropriate incentives for precaution on both sides. However, under any negligence rule, one of the two parties still bears whatever losses do occur – one party is the residual bearer of the harm of accidents, and the other party is not. Any negligence rule yields an efficient activity level by the residual risk bearer, but an inefficient activity level by the other party. Thus, the optimal rule depends on whose activity level is most important.

The Shavell paper on the syllabus, “Strict Liability versus Negligence,” is all about these incentives. Shavell looks at a number of different cases – accidents between strangers (such as car accidents), like we’ve been discussing, as well as accidents between sellers and their customers in a competitive market (which we’ll come back to at the end of today’s lecture), and accidents between sellers and strangers (other than their customers). In the case of sellers and customers, he points out that it is important to know whether the customers can perceive the riskiness of the products they buy. If they do not, then different liability rules can lead to very different results.

(The Shavell paper is an excellent read.)

Friedman has a different take on activity levels. He argues that reducing your activity level is just another type of precaution; but it’s a type of precaution where it’s impossible for the court to determine the efficient level. (A court might be able to figure out that it’s efficient for me to drive with my headlights on at night, but unable to figure out how many miles it’s optimal for me to drive in a given day. Therefore, a court might find me negligent if I was driving without headlights; but it’s hard for a court to decide whether a particular trip was socially efficient, and therefore whether I was negligent by being in my car!)

Instead of distinguishing precaution from activity levels, Friedman distinguishes observable precaution from unobservable precaution. He points out that any negligence rule only causes an efficient level of observable precaution, since that’s all that can be used to determine whether someone exercised due care or was negligent. So a negligence rule does not lead to an efficient level of unobservable precaution. Strict liability, on the other hand, leads the injurer to internalize the cost of accidents, so it leads to efficient levels of both observable and unobservable precaution – the same result as we already saw, just in different words. Friedman mentions that Posner uses this to explain why highly dangerous activities (blasting with dynamite, or keeping a lion as a pet) are often governed by strict liability; if they’re dangerous enough, the only meaningful type of precaution may be to not do them at all. Strict liability leads to efficient levels of both care (if you choose to do them) and a choice of whether or not to do them in the first place.

All our talk about negligence rules, and especially about efficiency, has been under the assumption that courts are able to set a legal standard of care equal to the efficient level. That is, a negligence rule gets the level of precaution to the legal standard x~. Efficiency requires it be set at the level that minimizes the total social cost of accidents, x*. So negligence rules are only efficient if x~ = x*.

In many cases, this is exactly what the courts try to do. This is based on a 1947 case, United States v Carroll Towing Company, in which Judge Learned Hand formulated a rule for deciding on negligence. The case (as described in Cooter and Ulen) was this:

A number of barges [in New York Harbor] were secured by a single mooring line to several piers. The defendant’s tug was hired to take one of the barges out to the harbor. In order to release the barge, the crew of the defendant’s tug, finding no one aboard in any of the barges, readjusted the mooring lines. The adjustment was not done properly, with the result that one of the barges later broke loose, collided with another ship, and sank with the cargo. The owner of the sunken barge sued the owner of the tug, claiming that the tug owner’s employees were negligent in readjusting the mooring lines. The tug owner replied that the barge owner was also negligent because his agent, called a “bargee,” was not on the barge when the tug’s crew sought to adjust the mooring lines. The bargee could have assured that the mooring lines were adjusted correctly.

Judge Learned Hand, in his decision, wrote the following:

It appears from the foregoing review that there is no general rule to determine when the absence of a bargee or other attendant will make the owner of a barge liable for injuries to other vessels if she breaks away from her moorings… Since there are occasions when every vessel will break away from her moorings, and since, if she does, she becomes a menace to those around her; the owner’s duty, as in other similar situations, to provide against resulting injuries is a function of three variables: (1) the probability that she will break away; (2) the gravity of the resulting injury, if she does; (3) the burden of adequate precautions. Possibly it serves to bring this notion into relief to state it in algebraic terms: if the probability be called P; the injury, L; and the burden, B; liability depends upon whether B is less than L multiplied by P. Thus, Judge Hand argued that if precaution (in this case, having a bargee on board your barge) cost less than its expected benefit, then it was negligent not to do it. So the legal standard for what constituted negligence was whether the precaution was efficient.

Since having an agent on board the barge is a yes-no decision, not a continuous variable, these were stated as absolutes; but if we reinterpret them as marginal terms, we get back to our old rule for efficiency: that if w, the incremental cost of precaution, is less than –p’A, the incremental benefit, the injurer is negligent. Implicitly, this is the same as setting the legal standard for care, x~, equal to the efficient level, x*.

Cooter and Ulen argue that successive application of the Hand rule over time will lead to people figuring out what the legal standard for precaution is. I’m careless, I cause an accident, I get sued. The court rules that a little more precaution would have been justified, so I’m held liable. The next guy is a little more careful; an accident happens, he gets sued, he’s found negligent. The next guy is a little more careful. Eventually, we reach a level of care where a little bit more would not have been cost-justified; that guy is found not to be negligent, and not held liable, and then we all know what level of care is required.

Another alternative, of course, is for laws and regulations to specify a legal standard. Highway officials could compute the efficient speed for a particular road – accounting for the value of getting somewhere sooner, and the effect of speed on the likelihood of accidents – and set the speed limit to the be efficient speed.

And of course, a third alternative is for the law to enforce social norms or best-practices of an industry when it comes to standards of care. That is, if a community or an industry has been facing this problem for a long time, and evolved its own norms or practices for what level of care is required, it’s plausible that this level is efficient, and the court may just choose to enforce it. The book gives the example of a residential community setting rules concerning the maintenance of steps leading up to houses, or the accounting industry having standards regarding auditing. All our analysis so far has been under the assumption of unilateral harm – that is, both the injurer and the victim may affect the likelihood of an accident, but all the direct harm from the accident is borne by the victim.

Obviously, in some cases, this isn’t true. Two cars collide on the highway – both cars end up damaged. Bilateral harm is harder to analyze. Often, the easiest thing is to hypothetically separate the accident into two separate events – the harm that happens to you (seeing you as victim and my as injurer), and the harm that happens to me (seeing me as victim and you as injurer). Often, this is what happens legally – both sides sue each other for damages. We’re not really going to deal with the case of bilateral harm – pretty tough to analyze.

Cooter and Ulen point out that American courts have consistently made a mistake in the way they’ve applied the Hand rule. In terms of calculating the efficient level of precaution, marginal cost should be balanced against the total social benefit of reducing accidents, which includes both the reduction in risk to the plaintiff (“risk to others”) and the risk to the injurer himself (“risk to self”). For example, when I drive recklessly, I risk hitting a pedestrian, and I also risk destroying my own car. The reduction in both these risks constitutes the social benefit of driving more carefully. However, courts have tended to only consider the reduction in “risk to others” when assessing the benefits of precaution.

(Cooter and Ulen also point out the idea of “hindsight bias” – once something happens, we tend to assume it was likely to happen. That is, if something is extremely low- probability, but then occurs, we may change our mind about how unlikely it initially was to happen. This would lead to an overestimate after the fact of the probability of an accident.) We’ve shown that a negligence rule creates efficient incentives for precaution by both the victim and the injurer, while a strict liability rule only creates efficient incentives for the injurer. However, over the course of the 1900s, the incidence of strict liability rules increased. Why?

The answer has to do with information. It’s easy to prove harm and causation – my coke bottle explodes and takes out my left eye. Clearly, I got hurt; and clearly, the bottle did it. It’s very hard to prove that Coca-Cola was negligent in their bottling process – I’d have to understand their whole manufacturing process, understand the likelihood of accidents, how the likelihood of accidents responds to precautionary measures they could have taken, and so on. Under a negligence rule, it might be too hard to prove negligence; and so the manufacturer might not have to take precautions, knowing they can avoid liability anyway. On the other hand, under strict liability, the company bears the cost of accidents, so it faces the incentive to reduce accidents directly, not just avoid having appeared negligent.

(To put it another way, negligence requires me to figure out the efficient level of care Coca-Cola should have taken; strict liability requires Coca-Cola to figure out the efficient level of care. If Coca-Cola has better knowledge of their manufacturing process than I do, this may be better.)

This leads us to errors and uncertainty in evaluating damages, and the effects that these have on incentives for precaution.

First, put aside the question of whether or not someone is liable, and think only about the problem of calculating the amount of damages owed. There are two types of mistakes a court can make: systematic mistakes, and random mistakes.

Random mistakes mean that, if an accident caused $10,000 in harm, the court might end up setting damages either higher or lower than $10,000, but on average will get it right. (DRAW IT.)

Systematic mistakes are when damages, on average, are set either higher or lower than the actual harm.

C and U refer to systematic mistakes as “errors,” and to random mistakes as “uncertainty”. First, let’s look at the effects of errors under a strict liability rule. Under a strict liability rule, the injurer minimizes the sum of two things: cost of precaution, plus expected damage payments. (With perfect compensation, damage payments = cost of accidents, and so the injurer minimizes the total social cost of accidents.)

Random errors in damages awarded have no effect on injurer incentives under a strict liability rule. This is because the injurer is only concerned with the expected level of damages he will have to pay; as long as damages are right on average, he will still internalize the expected cost of accidents, and still take the same level of precaution.

On the other hand, systematic errors in calculating damages will skew the injurer’s incentives. If damages are consistently set too low, then the injurer will not internalize the entire social cost of accidents; so precaution will be set too low. (DRAW IT.) If damages are consistently set too high, the injurer will internalize more than 100% of the social cost of accidents, so precaution will be set too high.

To sum up, under strict liability, systematic errors in setting damages will cause the injurer’s precaution level to respond in the same direction as the error; random errors in setting damages will have no effect.

Another way the court could err is to fail to find the injurer liable when it should. If the probability of being found liable is less than 100%, this has the same effect as lowering the expected level of damages that the injurer has to pay. (The injurer is indifferent between paying $10,000 in damages half the time, or paying $5,000 in damages for sure.) So a failure to consistently hold injurers liable has the same effect as a systematic error in setting damages too low:

Under strict liability, systematic errors in failing to hold injurers liable leads to less injurer precaution.

Next, we can look at the same incentives under a negligence rule. (DRAW IT.)

Here, the result is very different. Small errors in setting damages – either their amount, or whether they are awarded at all – will change how the injurer perceives the p(x)A curve. However, because of the discontinuity, small errors will not cause the injurer to change his behavior – it will still be optimal to take a precaution level of x~. So “modest” errors – either systematic or random – in setting damages will have no effect on precaution under a negligence rule.

Under a negligence rule, modest errors in setting damages will not affect injurer precaution. Similarly, occasional failures to hold negligent injurers liable will also not affect injurer precaution, so long as they are occasional. (If you have a 90% chance of being held liable when negligent, it’s the same as being charged 90% of the proper level of damages; it probably isn’t enough to change your behavior under a negligence rule.) Of course, large enough errors in either measure could cause the p(x) D curve to dip below the level of w x*, in which case they would have an effect.

(C and U also point out that these errors can be thought of as court errors in setting appropriate damages, or as injurer errors in predicting the level of damages. Again, neither one leads to a change in precaution level under a negligence rule, so long as the errors are not too large.)

Of course, under a negligence rule, the court also has to rule on whether the legal standard of care was met, that is, the court has to compare the care the injurer took, x, to the legal standard, x~, which we hope is set equal to the efficient level, x*. Systematic errors in the standard of care have a very direct effect on injurer precaution.

(DRAW IT)

In general, under a negligence rule, the injurer’s level of precaution responds exactly to systematic court errors in setting the legal standard.

What about random errors? Here, the result is a little bit harder to see. I don’t want to get into the technical details of it, small amounts of uncertainty about the legal standard will lead to firms taking higher precaution. That is

(DRAW IT)

In general, under a negligence rule, small random errors in the legal standard of care cause the injurer to increase precaution.

Given these results, C and U argue that when courts are able to assess damages more accurately than standards of care, a strict liability rule is better; when a court can assess standards more accurately than damages, a negligence rule is better. Also, they point out that when the standard of care is vague, that is, when there is uncertainty about what does and does not constitute negligence, the court should err on the side of leniency, so as not to further aggravate the problem of excessive precaution. (The book does a little aside on “bright-line” rules, like speed limits, versus vague standards, like “don’t drive recklessly”. In certain settings, laws won’t be enforced if they’re overly vague. Off-topic a bit, but California helmet law.)

Cooter and Ulen talk a bit about the different costs of administering different liability systems. Obviously, it’s simpler to prove just harm and causation than to prove harm, causation, and negligence; so once a case goes to court, we expect the administrative costs to be higher under a negligence rule than under strict liability. (More time spent, more witnesses, etc.)

On the other hand, under a negligence rule, many victims will know they have no case, and therefore not bring a lawsuit at all; under a strict liability rule, every accident victim is entitled to damages, so there will be more lawsuits. So strict liability will lead to more cases, but easier cases.

Obviously, a rule of no liability leads to lower administrative costs than either, since there’s no work to be done.

C and U also point out the tradeoff between rules (such as the legal standard of care) which are tailored to individual situations, versus broad, simple rules that apply to many situations. As we’d expect, broad, simple rules are cheaper to create and enforce, but will not create perfect incentives in every situation; more specific, detailed, “tailored” rules will be more costly to create and enforce, but will create more efficient incentives.

In addition, there is the question of who bears some of these administrative costs. In some countries, victims who win at trial also have their legal expenses paid by the injurer; in the U.S., this tends not to be the case. The final bit in Cooter and Ulen in chapter 8 is on consumer product liability. If we assume that a product is being sold in a perfectly competitive market, then whether the manufacturer bears liability for defective products will affect the price of the product, and through that, the amount of the product that is consumed. I like the explanation in the Shavell paper better than the example in the textbook, so let’s work with that.

Consider the risk of getting food poisoning while eating in a restaurant. Assume that restaurants are in a perfectly competitive market, so the price you pay reflects total cost to the restaurant of running the business and preparing your food.

Under a negligence rule, the restaurant will avoid liability, by taking the appropriate precautions in preparing the food. Therefore, the restaurant will not be liable for any accidental food-poisoning cases that do occur; so the price they charge will not include this risk.

If customers can correctly perceive the risk of getting sick, then everything’s fine; the total cost to a customer of eating the meal is the price they pay for the food, plus the expected accident losses due to sickness. Customers therefore demand the socially optimal amount of restaurant food.

However, if customers underestimate the risk of food poisoning, they will consume too much restaurant food; if they overestimate the risk, they will consume too little.

Under a strict liability rule, the restaurant is liable for any food poisoning that occurs, so they again take efficient precautions. Since they remain liable, the expected losses due to accidents are built into the price they charge for the food. (That is, prices are higher, since they now include the expected damages the restaurant must pay.) Now customers demand the right number of meals, regardless of whether they can correctly assess the risk, since the price of food poisoning is already built into the price of the food. That is, the “total” price of the meal is exactly the price the customer is being charged (since he doesn’t bear the residual food poisoning risk), and so it’s easy for him to consume the right number of restaurant meals. Under no liability, the outcome depends very sharply on how well the customers can estimate the risk associated with each particular seller. If sellers know the risk of food poisoning at each restaurant, they can build these losses into the price they expect to pay, and demand the socially efficient amount of food. If a restaurant took more risks in food preparation in order to reduce prices, customers would also adjust the total cost they considered due to the higher risk; the restaurant would still have an incentive to take the correct level of precaution, and the customer would demand the efficient amount of food.

Next, Shavell considers what would happen under no liability if customers could not perceive the risk associated with each particular restaurant, but did know the overall (average) risk associated with eating in restaurants. In that case, restaurants have no incentive to take adequate care, since it would not be rewarded with higher sales. If customers perceived industry-average risks but not risks from each individual firm, each restaurant would take no precautions; but the customer would at least realize that eating at restaurants was risky, and would, given the risk, consume the efficient number of meals.

Of course, if customers cannot perceive even the average level of risk in the industry, restaurants have no incentive to take precautions, and customers demand an inefficiently high number of meals given the risk.

We can summarize these results like so:

Liability Rule Risk Perception Seller Buyer Activity Precaution Strict Liability Yes Efficient Efficient No Efficient Efficient Negligence Yes Efficient Efficient No Efficient Too High No Liability Yes Efficient Efficient Average None Efficient No None Too High

(Cooter and Ulen do a similar example with coke bottles versus cans. I don’t like their treatment as much. Check out the Shavell paper if you’re fuzzy on this. Skip the formal model – the introduction tells the story very well.)

That’s it for a theory of tort law. Next week, we’ll begin with applications.