High Speed Rail (West Midlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sneyds of Keele Hall, Staffordshire Uncalendared

SPECIAL COLLECTIONS AND ARCHIVES TEL: 01782 733237 EMAIL: [email protected] LIBRARY Ref code: GB 172 S Sneyds of Keele Hall, Staffordshire Uncalendared family papers Deeds General schedules of deeds, abstracts of title, lists 1-2 Deeds: Abbey Hulton to Keele 2-101 Librarian: Paul Reynolds Library Telephone: (01782) 733232 Fax: (01782) 734502 Keele University, Staffordshire, ST5 5BG, United Kingdom Tel: +44(0)1782 732000 http://www.keele.ac.uk This l i s t supersedes the summary l i s t of the Sneyd Papers issued by the John Rylands Library, Manchester, in November 1950. It classifies the material and allots a permanent reference number to each item. The Sneyd Papers were at Keele Hall after the Second World War, when they were purchased by Mr Raymond Richards, of Gawswcrth, from Cci« Balph Sneyd (1863-1949), the family’ s last direct descendant. After adding the rescued papers to his collection Mr Richards placed the bulk of it in the John Rylands Library, on deposit. The University of Keele (then the University College of North Staffordshire) purchased most of the collection in 1957 and the Sneyd Papers therefore returned to Keele, where they are now housed in the University Library. From the time of the Civil War the accumulation lias had its ups and downs and damage in terms of actual losses (particularly in the map department) accounts for a noticeable imbalance. Over- the years fa irly extensive disturbance has resulted in fragmentation of the archive and the number of items listed in isolation is consequently high. It is possible that some items now incorporated with the family papers were collected by the Rev. -

Madeley HNA Finalversion.3.0

Madeley Neighbourhood Plan Housing Needs Assessment December 2017 Madeley Housing Needs Assessment DRAFT Quality information Prepared by Checked by Approved by Ivan Tennant, Principal Jesse Honey – Associate Planner Director Paul Copeland, Senior Planner Revision History Revision Revision Details Authorized Name Position date Draft 02/10/2017 Tech Review JH Jesse Honey Associate Director Final Draft 16/11/2017 Group NS Nick Review Speakman Final Draft 20/11/2017 Proof Read MK Mary Project Co- Kucharska Ordinator AECOM Madeley Housing Needs Assessment DRAFT Prepared for: Madeley Parish Council Prepared by: AECOM Limited Aldgate Tower 2 Leman Street London E1 8FA aecom.com © 2017 AECOM Limited. All Rights Reserved. This document has been prepared by AECOM Limited (“AECOM”) for sole use of Madeley Parish (the “Client”) in accordance with generally accepted consultancy principles, the budget for fees and the terms of reference agreed between AECOM and the Client. Any information provided by third parties and referred to herein has not been checked or verified by AECOM, unless otherwise expressly stated in the document. No third party may rely upon this document without the prior and express written agreement of AECOM. AECOM Madeley Housing Needs Assessment DRAFT Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary ........................................................................................ 1-6 2. Context ............................................................................................................ 15 2.1 Local context .......................................................................................... -

Newcastle-Under-Lyme and Stoke-On-Trent Core Spatial Strategy Examination

NEWCASTLE-UNDER-LYME AND STOKE-ON-TRENT CORE SPATIAL STRATEGY EXAMINATION DOCUMENT CCD4 Response to Planning Inspector’s Question (ICD4) (a) Clarification as to the relationship between demolitions and the housing targets in the CS. What do the ‘net’ and ‘gross’ figures include? 1. Strategic housing development targets (net additional dwellings 2006 – 2026) are currently set out in the seventh row of the table at paragraph 5.25 of the Core Spatial Strategy. These are derived from the West Midlands Regional Spatial Strategy Preferred Option (RSS/002 – Policy CF3, Table 1). They are ‘net’ figures and represent the increase in housing stock over the plan period excluding allowance for demolition replacements and changes as a result of conversions / changes of use. ‘Gross’ figures comprise the ‘net’ figure plus a notional allowance for replacement of demolished dwellings over the plan period. (b) Do the Councils’ figures for completions include or exclude demolition replacements? 2. In respect of Stoke-on-Trent, the completion figure for 2006/07, shown in the first row of the published table at paragraph 5.25 of the Core Spatial Strategy is a ‘net’ figure. Thus allowance is made for demolitions, conversions and changes of use within that year. In Stoke-on-Trent this means 850 completions (gross) less 219 demolitions less 15 changes of use out of housing. 3. In respect of Newcastle-under-Lyme the completion figure for 2006/07, shown in the first row of the published table at paragraph 5.25 of the Core Spatial Strategy is a ‘gross’ figure. The net additional dwellings are calculated by deducting the number of demolitions from the gross completion figures. -

Newcastle-Under-Lyme Local Development Framework Annual

Newcastle-under-Lyme Local Development Framework Annual Monitoring Report December 2007 NEWCASTLE BOROUGH CHESHIRE - Congleton Borough KEY SETTLEMENTS STAFFORDSHIRE MOORLANDS Kidsgrove M6 Audley WEST COAST MAIN LINE Chesterton BOROUGH OF NEWCASTLE CITY OF STOKE CHESHIRE - Crewe & UNDER LYME ON TRENT Nantwich Borough Knutton Silverdale Newcastle-under-Lyme Madeley SHROPSHIRE - North Shropshire WEST COAST MAIN LINE Loggerheads STAFFORD BOROUGH 0 4km n Newcastle under Lyme Local Development Framework – Annual Monitoring Report 2007 Newcastle under Lyme Annual Monitoring Report 2007 Contents Newcastle under Lyme Annual Monitoring Report 2007................................1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................2 1. Introduction................................................................................................5 2. The Monitoring Framework.......................................................................6 3. Local Development Scheme implementation..........................................7 4. The key characteristics of the Borough of Newcastle under Lyme.....11 5. Policy Monitoring.....................................................................................18 5.1 Sustainable Development..................................................................19 5.2 Housing...............................................................................................23 5.3 Employment and economic development........................................29 5.4 Retail and -

Land at Pepper Street, Keele, Newcastle Under Lyme St5 6Qq for Sale

FOR SALE RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY A RESERVED MATTERS PLANNING PERMISSION AND A REMEDIATED SITE NEWCASTLE- ROYAL STOKE M6 UNDER-LYME UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL SEDDON HOMES ‘THE HAWTHORNS’ HERITAGE PARK A 52 5 KE EL E RO AD PEP PER STRE ET (B 5044) 13 ACRES Land at Pepper Street, Keele, Newcastle Under Lyme, ST5 6QQ FOR SALE – RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY LAND AT PEPPER STREET, KEELE, NEWCASTLE UNDER LYME ST5 6QQ T E E R T S R E P P E P 4 4 0 5 B INDICATIVE OUTLINE A629 DEWSBURY PONTEFRACT TARLETON A638 40 WAKEFIELD M62 35 A666 24 8 23 A644 A628 A565 M6 M62 A640 A638 A19 CHORLEY A642 39 SOUTHPORT LITTLEBOROUGH HUDDERSFIELD A1(M) M18 A59 1 A58 22 A666 A637 HEMSWORTHA638 6 M66 ROCHDALE 36 ASKERN A570 THORNE CROWLE A5209 HORWICHA58 A58 A58 21 A628 2 DENSHAW 5 A59 27 A5209 A673 BURY 20 M1 A19 1 M61 A58 36 A565 6 BOLTON A627(M) A629 A637 A628 ORMSKIRK A676 A56 HOLMFIRTH A6195 ADWICK 2 A49 A666 5 A58 FORMBY 4 LE STREET 18 BARNSLEY A630 M180 A570 SKELMERSDALE A58 A628 37 A635 A59 WIGAN 17 19 A663 OLDHAM 37 3 3 A635 4 26 A577 A62 A18 2 A56 GOLDTHORPE 15 21 A627 PENISTONE EPWORTH M58 A49 WALKDEN A576 22 DONCASTER 1 A663 A629 M18 A5758 A579 SALFORD A638 A570 A62 A616 A565 25 A580 M60 A6195 36 A6182 A580 MANCHESTER 36 A506 12 24 1 A6010 A6018 3 2 23 35 A5036 M6 A665 35a FINNINGLEY 3 A635 A6017 2 11 ECCLES A628 A59 A580 23 A616 4 A570 A58 A5081 M67 A565 A57 1a A638 ST HELENS A579 9 A56 A57 24 4 35 A580 M57 M62 A5103 A61 M18 A1(M) A58 A6 HYDE MISTERTON BOOTLE 22 A5145 GLOSSOP A5058 3 A49 11 7 A631 A5089 2 A570 21a M60 A34 A560 ROTHERHAM BAWTRY -

The Mining Industry in North Staffordshire, a Personal Perspective

The Mining Industry in North Staffordshire A Personal Perspective by Jim Worgan The Mining Industry in North Staffordshire A Personal Perspective by Jim Worgan Silverdale Colliery closed on the 31st December 1998, thus bringing to an end over 800 years of coal and ironstone mining in North Staffordshire. At its height the industry employed over 30,000 men and women and output reached 7 million tons of coal and 2½ million tons of ironstone per annum. Today many buildings and monuments dot the skyline, the most significant being:- a) Chatterley Whitfield Colliery which closed in 1977 and then opened as the first ever underground Mining Museum in Great Britain in 1979. Shortly before it closed in August 1993 the site became scheduled as an Ancient Monument comprising 34 buildings dating from 1883 to the 1960s, most of which are scheduled or listed. It is the most complete coal mine in Great Britain and possibly Western Europe. Most of the site, which amongst others contains the headgears (metal structures and pulley wheels) of the Hesketh, Platt, Institute and Winstanley shafts, is derelict although two or three buildings have been restored. These are now in use for commercial purposes and by the Chatterley Whitfield Friends (a Charity Organisation) who are doing everything they can “to keep the site alive”. They have a large archive of photographs, documents, plans/maps and artefacts and their Heritage Centre on site is normally open to the public by appointment. b) Foxfield Colliery at Godley Brook (Dilhorne) in the Cheadle Coalfield where most of the former colliery site survives. -

Sneyds of Keele Hall, Staffordshire Uncalendared Family Papers

SPECIAL COLLECTIONS AND ARCHIVES TEL: 01782 733237 EMAIL: [email protected] LIBRARY Ref code: GB 172 S Sneyds of Keele Hall, Staffordshire Uncalendared family papers Deeds Deeds: Kirkhallam-Yarnfield 102-204 Deeds: Places unspecified, miscellaneous 204-211 Librarian: Paul Reynolds Library Telephone: (01782) 733232 Fax: (01782) 734502 Keele University, Staffordshire, ST5 5BG, United Kingdom Tel: +44(0)1782 732000 http://www.keele.ac.uk This l i s t supersedes the summary l i s t of the Sneyd Papers issued by the John Rylands Library, Manchester, in November 1950. It classifies the material and allots a permanent reference number to each item. The Sneyd Papers were at Keele Hall after the Second World War, when they were purchased by Mr Raymond Richards, of Gawswcrth, from Cci« Balph Sneyd (1863-1949), the family’ s last direct descendant. After adding the rescued papers to his collection Mr Richards placed the bulk of it in the John Rylands Library, on deposit. The University of Keele (then the University College of North Staffordshire) purchased most of the collection in 1957 and the Sneyd Papers therefore returned to Keele, where they are now housed in the University Library. From the time of the Civil War the accumulation lias had its ups and downs and damage in terms of actual losses (particularly in the map department) accounts for a noticeable imbalance. Over- the years fa irly extensive disturbance has resulted in fragmentation of the archive and the number of items listed in isolation is consequently high. It is possible that some items now incorporated with the family papers were collected by the Rev. -

In Your Area Whitmore Heath to Madeley

June 2020 | www.hs2.org.uk In your area Whitmore Heath to Madeley Chorlton Balterley A34 Chesterton High Speed Two (HS2) A531 Halmer End is the new high speed Betley railway for Britain. Alsagers Bank A527 HS2 Ltd is the company Blakenhall Wrinehill responsible for Leycett Silverdale M6 developing the railway. Checkley Newcastle-under-Lyme A525 We’re currently seeking Keele Madeley Heath Parliamentary approval to build and run Phase A51 Madeley A53 2a of HS2: West Clayton Midlands to Crewe, Onneley which we expect Woore to achieve in 2020. Shropshire A5182 Madeley Park Whitmore Pipe Gate Aston Hanchurch Dorrington Baldwin’s Gate HS2 Phase 2a Knighton Knowl Wall Blackbrook Beech Maer Chapel Chartlon Mucklestone Ashley Introduction We’ve produced this booklet to update you on the route from Whitmore Heath to Madeley. It includes: • a summary and map of the proposed route in the area; • how Phase 2a is being developed and what’s next; • the benefits that HS2 will bring to your region and to the country; • support for communities and property owners; and • information on how to get in touch with us. The route of Phase 2a from Whitmore Heath to Madeley The Whitmore Heath to Madeley area covers approximately 9.1km the Phase 2a route, which passes through the parishes of Whitmore and Madeley, within the Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council and Staffordshire County Council areas. The boundary between Swynnerton and Whitmore parishes forms the southern boundary of this area. The boundary between Madeley and Checkley cum Wrinehill parishes forms the northern boundary. The area is predominantly rural in character, with agriculture being the main land use. -

Summary List

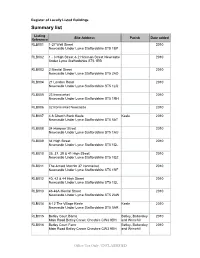

Register of Locally Listed Buildings Summary list Listing Site Address Parish Date added Reference RLB001 1-27 Well Street 2010 Newcastle Under Lyme Staffordshire ST5 1BP RLB002 1 - 3 High Street & 2 Hickman Street Newcastle 2010 Under Lyme Staffordshire ST5 1RB RLB003 2 Merrial Street 2010 Newcastle Under Lyme Staffordshire ST5 2AD RLB004 21 London Road 2010 Newcastle Under Lyme Staffordshire ST5 1LQ RLB005 23 Ironmarket 2010 Newcastle Under Lyme Staffordshire ST5 1RH RLB006 32 Ironmarket Newcastle 2010 RLB007 4-6 Church Bank Keele Keele 2010 Newcastle Under Lyme Staffordshire ST5 5AT RLB008 34 Hanover Street 2010 Newcastle Under Lyme Staffordshire ST5 1AU RLB009 34 High Street 2010 Newcastle Under Lyme Staffordshire ST5 1QL RLB010 35, 37, 39 & 41 High Street 2010 Newcastle Under Lyme Staffordshire ST5 1QZ RLB011 The Arnold Machin 37 Ironmarket 2010 Newcastle Under Lyme Staffordshire ST5 1RF RLB012 40, 42 & 44 High Street 2010 Newcastle Under Lyme Staffordshire ST5 1QL RLB013 46-46A Merrial Street 2010 Newcastle Under Lyme Staffordshire ST5 2AW RLB014 6-12 The Village Keele Keele 2010 Newcastle Under Lyme Staffordshire ST5 5AR RLB015 Betley Court Barns Betley, Baltereley 2010 Main Road Betley Crewe Cheshire CW3 9BH and Wrinehill RLB016 Betley Court Farm Betley, Baltereley 2010 Main Road Betley Crewe Cheshire CW3 9BH and Wrinehill Office Use Only: UNCLASSIFIED Listing Site Address Parish Date added Reference RLB017 Oaklea House Oaklea Court Bignall End Road Audley 2011 Bignall End Stoke On Trent Staffordshire ST7 8NU RLB018 The Boat And Horses Stubbs Gate 2010 Newcastle Under Lyme Staffordshire ST5 1LU RLB019 Bow End House Betley, Baltereley 2010 Main Road Betley Crewe Cheshire CW3 9AB and Wrinehill RLB020 Brampton Vale 2010 Brampton Road Newcastle-Under-Lyme Staffordshire ST5 0UJ RLB021 Bulls Vaults P.H. -

All Saints' Madeley and St Margaret's Betley

Welcome Thank you for your interest in becoming the All Saints’ Madeley new vicar of the Staffordshire parishes of All Saints’ Madeley and St. Margaret’s Betley. and We hope you will find all the information you need in this profile and that the following pages give you a flavour of our churches and St Margaret’s Betley the parishes we serve. We pray that the Holy Spirit will guide us, and you, in making decisions about who will join us as we take forward our visions of ministry within our churches and to our wider communities. Melanie Deacon Kevin Hamer Elizabeth Walklett Jennifer Walton Churchwardens, Churchwardens, All Saints’, St. Margaret’s, Madeley Betley The Parishes together Parishes The August 2020 Celebrating God ’s love 1 Contents The parishes together 2 ◆ Our new vicar: 6 All Saints’ Madeley and St Margaret’s Betley ◆ The person we seek and what we offer These two thriving parishes, held in plurality, each serve different village communities. ◆ All Saints’ Madeley 8 We are energetic and proactive in our commitment to the Madeley: the village 15 mission of Christ’s church, looking outwards to our ◆ communities and using our different traditions and talents to Betley: the village 17 make known the ‘inexhaustible riches and generosity of Christ’. ◆ Both parishes are intent on helping people understand and respond to the message of the Gospel. St Margaret’s Betley 20 ◆ The two parishes came together in plurality in 2002, and the Appendix: 29 relationship between us has grown steadily since then to ◆ Service patterns and attendance mutual benefit. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Planning Committee, 27/04/2021 19:00

Public Document Pack Date of Tuesday, 27th April, 2021 meeting Time 7.00 pm Venue Hybrid Meeting - Castle Contact Geoff Durham 742222 Castle House Barracks Road Newcastle-under-Lyme Staffordshire ST5 1BL Planning Committee AGENDA PART 1 – OPEN AGENDA 1 APOLOGIES 2 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST To receive Declarations of Interest from Members on items included on the agenda. 3 MINUTES OF PREVIOUS MEETING(S) (Pages 5 - 10) To consider the minutes of the previous meeting(s). 4 APPLICATION FOR MAJOR DEVELOPMENT - LAND (Pages 11 - 16) ADJACENT KEELE UNIVERSITY, KEELE ROAD, KEELE. MR KARL BROWN, HLM ARCHITECTS. 21/00222/FUL 5 APPLICATION FOR MINOR DEVELOPMENT - 22 KING STREET, (Pages 17 - 26) CROSS HEATH . MR K NIJJAR. 21/00067/FUL This item includes a supplementary report. 6 APPLICATION FOR MINOR DEVELOPMENT - HOPE COTTAGE, (Pages 27 - 34) LEYCETT LANE. MR & MRS J BULLOCK. 21/00193/FUL 7 APPLICATION FOR MINOR DEVELOPMENT - SCOT HAY (Pages 35 - 44) FARM, LEYCETT ROAD. MR DENNIS MARK HOLFORD. 21/00005/FUL This item includes a supplementary report. 8 APPLICATION FOR MINOR DEVELOPMENT - LAND AT (Pages 45 - 56) DODDLESPOOL, MAIN ROAD, BETLEY. MR. MARK OULTON. 21/00286/FUL Contacting the Council: Switchboard 01782 717717 . Text 07800 140048 Email [email protected]. www.newcastle-staffs.gov.uk This item includes a supplementary report. 9 APPLICATION FOR OTHER DEVELOPMENT - OLD HALL, (Pages 57 - 66) POOLSIDE, MADELEY. MR GARY WHITE. 21/00206/LBC This item includes two supplementary reports. 10 5 BOGGS COTTAGE, KEELE. 14/00036/207C3 (Pages 67 - 68) 11 LAND AT DODDLESPOOL, BETLEY. 17/00186/207C2 (Pages 69 - 72) This item includes a supplementary report. -

Trader Register Report

Trader Region: Added by Staffordshire & Stoke Partnership Company Name: Wilcox Plumbing & Heating Ltd Street Address: Unit 19 West Cannock Way, Cannock Chase Enterprise Centre City / Town: Hednesford Postcode: WS125QU Company Website: http://www.wilcoxplumbing.com Company Number: 6376714 Distance from you: 0.00Miles Contact First Name: Darren Contact Last Name: Wilcox Contact Telephone: 01543 458074 Contact Mobile: 07970 076582 Contact Email: [email protected] Contact Fax: Trader Region: Added by Staffordshire & Stoke Partnership Company Name: Hine Plumbing Services Ltd Street Address: Bent Head Farm, City / Town: Leek Postcode: ST13 8SP Company Website: http://www.hine.uk.com Company Number: 04883692 Distance from you: 0.00Miles Contact First Name: Peter Contact Last Name: Hine Contact Telephone: 01538 300334 Contact Mobile: 07973 135664 / 07977 517342 Contact Email: [email protected] Contact Fax: Trader Region: Added by Staffordshire & Stoke Partnership Company Name: Brenden Fern Ltd Street Address: 493 High Street, Sandyford City / Town: Stoke-on-Trent Postcode: ST6 5PB Company Website: http://www.bflimited.co.uk Company Number: 4520879 Distance from you: 0.00Miles Contact First Name: Brenden Contact Last Name: Fern Contact Telephone: 01782 818577 Contact Mobile: 07866 670406 Contact Email: [email protected] Contact Fax: 01782818578 Trader Region: Added by Staffordshire & Stoke Partnership Company Name: D B Plumbing and Heating Limited Street Address: 33 The Meadows, Endon City / Town: Stoke on Trent Postcode: ST9 9BG