The Mining Industry in North Staffordshire, a Personal Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

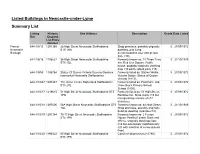

Listed Buildings in Newcastle-Under-Lyme Summary List

Listed Buildings in Newcastle-under-Lyme Summary List Listing Historic Site Address Description Grade Date Listed Ref. England List Entry Number Former 644-1/8/15 1291369 28 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire Shop premises, possibly originally II 27/09/1972 Newcastle ST5 1RA dwelling, with living Borough accommodation over and at rear (late c18). 644-1/8/16 1196521 36 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire Formerly known as: 14 Three Tuns II 21/10/1949 ST5 1QL Inn, Red Lion Square. Public house, probably originally dwelling (late c16 partly rebuilt early c19). 644-1/9/55 1196764 Statue Of Queen Victoria Queens Gardens Formerly listed as: Station Walks, II 27/09/1972 Ironmarket Newcastle Staffordshire Victoria Statue. Statue of Queen Victoria (1913). 644-1/10/47 1297487 The Orme Centre Higherland Staffordshire Formerly listed as: Pool Dam, Old II 27/09/1972 ST5 2TE Orme Boy's Primary School. School (1850). 644-1/10/17 1219615 51 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire ST5 Formerly listed as: 51 High Street, II 27/09/1972 1PN Rainbow Inn. Shop (early c19 but incorporating remains of c17 structure). 644-1/10/18 1297606 56A High Street Newcastle Staffordshire ST5 Formerly known as: 44 High Street. II 21/10/1949 1QL Shop premises, possibly originally build as dwelling (mid-late c18). 644-1/10/19 1291384 75-77 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire Formerly known as: 2 Fenton II 27/09/1972 ST5 1PN House, Penkhull street. Bank and offices, originally dwellings (late c18 but extensively modified early c20 with insertion of a new ground floor). 644-1/10/20 1196522 85 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire Commercial premises (c1790). -

Mineral Resources Report for Staffordshire

BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY TECHNICAL REPORT WF/95/5/ Mineral Resources Series Mineral Resource Information for Development Plans Staffordshire: Resources and Constraints D E Highley and D G Cameron Contributors: D P Piper, D J Harrison and S Holloway Planning Consultant: J F Cowley Mineral & Resource Planning Associates This report accompanies the 1:100 000 scale maps: Staffordshire Mineral resources (other than sand and gravel) and Staffordshire Sand and Gravel Resources Cover Photograph Cauldon limestone quarry at Waterhouses, 1977.(Blue Circle Industries) British Geological Survey Photographs. No. L2006. This report is prepared for the Department of the Environment. (Contract PECD7/1/443) Bibliographic Reference Highley, D E, and Cameron, D G. 1995. Mineral Resource Information for Development Plans Staffordshire: Resources and Constraints. British Geological Survey Technical Report WF/95/5/ © Crown copyright Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 1995 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of Survey publications is available from the BGS British Geological Survey Offices Sales Desk at the Survey headquarters, Keyworth, Nottingham. The more popular maps and books may be purchased from BGS- Keyworth, Nottingham NG12 5GG approved stockists and agents and over the counter at the 0115–936 3100 Fax 0115–936 3200 Bookshop, Gallery 37, Natural History Museum (Earth Galleries), e-mail: sales @bgs.ac.uk www.bgs.ac.uk Cromwell Road, London. Sales desks are also located at the BGS BGS Internet Shop: London Information Office, and at Murchison House, Edinburgh. www.british-geological-survey.co.uk The London Information Office maintains a reference collection of BGS publications including maps for consultation. Some BGS Murchison House, West Mains Road, books and reports may also be obtained from the Stationery Office Edinburgh EH9 3LA Publications Centre or from the Stationery Office bookshops and 0131–667 1000 Fax 0131–668 2683 agents. -

Scsl Handbook 2021 22

1 2 STAFFORDSHIRE COUNTY SENIOR LEAGUE Incorporating the Staffordshire County League (Founded in 1900) & the Midland League (Founded 1984) MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE PRESIDENT J.T. Phillips VICE PRESIDENTS M. Stokes Tel: 01543 878075 E-mail: [email protected] A Harrison Mobile 07789 632145 E-mail [email protected] CHAIRMAN R. Crawford 07761 514909(M) E-mail: [email protected] Twitter: @scslchair VICE CHAIRMAN M. Stokes Tel: 01543 878075 E-mail: [email protected] LEAGUE SECRETARY C. Jackson E-mail: [email protected] 07761 514912(SecretarY ) 07763171456(M) TREASURER R. Bestwick Tel: 07967193546(M) Email: [email protected] REFEREE APPOINTMENTS SECRETARY R. Barlow Tel; 01782 513926, 07792412182 (M) E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] 3 FIXTURES TEAM R.Crawford R Bestwick D.Bilbie RESULTS SECRETARY D. Bilbie Mobile 07514786146 E-mail: [email protected] I.T. SUPPORT & DEVELOPMENT R. Bestwick, Tel: 07967193546(M) E mail: [email protected] DISCIPLINE SECRETARY S Matthews Tel ; 07761 514921 E-mail : [email protected] GROUNDS SECRETARY M. Sutton Tel: 07733098929(M) E-mail: [email protected] ELECTED OFFICERS & CLUB REPRESENTATIVES J.H. Powner J.Hilditch C.Humphries J.Greenwood J.Nealon WELFARE OFFICER & CLUB REPRESENTATIVE Mrs G Salt Tel: 07761 514919 E-mail: [email protected] LIFE MEMBER P. Savage M. Stokes 4 DISCIPLINE COMMITTEE S. Matthews P. Savage R. Crawford R. Barlow J.T. Phillips J.H. Powner M Stokes GROUNDS COMMITTEE M. Sutton J.T. Phillips M. Stokes P. Savage D. Vickers J. Cotton DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE FINANCE SUB R. Bestwick J.H. -

Submission to the Local Boundary Commission for England Further Electoral Review of Staffordshire Stage 1 Consultation

Submission to the Local Boundary Commission for England Further Electoral Review of Staffordshire Stage 1 Consultation Proposals for a new pattern of divisions Produced by Peter McKenzie, Richard Cressey and Mark Sproston Contents 1 Introduction ...............................................................................................................1 2 Approach to Developing Proposals.........................................................................1 3 Summary of Proposals .............................................................................................2 4 Cannock Chase District Council Area .....................................................................4 5 East Staffordshire Borough Council area ...............................................................9 6 Lichfield District Council Area ...............................................................................14 7 Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council Area ....................................................18 8 South Staffordshire District Council Area.............................................................25 9 Stafford Borough Council Area..............................................................................31 10 Staffordshire Moorlands District Council Area.....................................................38 11 Tamworth Borough Council Area...........................................................................41 12 Conclusions.............................................................................................................45 -

Approved Minutes Annual Parish, Allot

72 ………………………………………………………Signed ………………………..Dated AUDLEY RURAL PARISH COUNCIL MINUTES OF THE ALLOTMENT COMMITTEE MEETING held in Audley Pensioners Hall 17 th April 2014 at 6.30pm Present: Chairman: Mr T Sproston Councillors: Mr H Proctor, Mrs V Pearson, Mr P Breuer, Mr N Blackwood, Mr A Wemyss, Mr C Cooper, Mr P Morgan, Mrs A Beech and Mr M Dolman. Clerk – Mrs C. Withington Mr Neil Breeze, Mrs Holleen Breeze, Mrs Linda Johnson – Halmer End Mrs Pam Patten, Ms Rachel Bailey and Mr Roger Beech – Audley Allotments No. Item Action 1. To receive apologies Apologies were received from Mrs K Davison, Mrs C D Cornes, Mr E Durber, Mr D Cornes, Mrs B Kinnersley and Lewis Moore. 2. Approval of minutes from last meeting 21 st March 2013 These were approved as a true and accurate record and signed at the meeting. 3. Agreement of siting of allotment fencing with Audley Allotment Association – letter from Audley Millennium Green Trust Brief discussion took place, following Mr Blackwood reading a letter on behalf of the Millennium Green Trust raising concerns about the process of carrying out the fencing work by the Allotment Association and where it has been sited, although it was noted there were no concerns with the quality of the work. Noted that further work was required to complete the job. RESOLVED that a site visit would take place with the MGT Chair, Parish Council and Audley Allotment Association to discuss the concerns and resolve the issues. This will be brought back to a future meeting. Site visit arranged for Thursday 24 th April 2014 at 6pm – Mrs Pearson gave her apologies. -

Economic Needs Assessment Newcastle-Under-Lyme & Stoke-On-Trent

Economic Needs Assessment Newcastle-under-Lyme & Stoke-on-Trent June 2020 Contents Executive Summary i 1. Introduction 1 2. National Policy and Guidance 4 3. Economic and Spatial Context 8 4. Local Economic Health-check 19 5. Overview of Employment Space 40 6. Commercial Property Market Review 59 7. Review of Employment Sites 81 8. Demand Assessment 93 9. Demand / Supply Balance 120 10. Strategic Sites Assessment 137 11. Summary and Conclusions 148 Appendix 1: Site Assessment Criteria Appendix 2: Site Assessment Proformas Appendix 3: Sector to Use Class Matrix Our reference NEWP3004 This report was commissioned in February 2020, and largely drafted over the period to June in line with the original programme for the Joint Local Plan. Discrete elements of the analysis, purely relating to supply, were completed beyond this point due to the limitations of lockdown. Executive Summary 1. This Economic Needs Assessment has been produced by Turley – alongside a separate but linked Housing Needs Assessment (HNA) – on behalf of Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council and Stoke-on-Trent City Council (‘the Councils’). It is intended to update their employment land evidence, last reviewed in 20151, and comply with national planning policy that has since been revised2. It provides evidence to inform the preparation of a Joint Local Plan, while establishing links with ambitious economic strategies that already exist to address local and wider priorities in this area. 2. It should be noted at the outset that while this report takes a long-term view guided by trends historically observed over a reasonable period of time, it has unfortunately been produced at a time of exceptional economic volatility. -

2495 09 April 2021

Office of the Traffic Commissioner (West Midlands) Notices and Proceedings Publication Number: 2495 Publication Date: 09/04/2021 Objection Deadline Date: 30/04/2021 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (West Midlands) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Website: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 09/04/2021 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] Remember to keep your bus registrations up to date - check yours on https://www.gov.uk/manage-commercial-vehicle-operator-licence-online PLEASE NOTE THE PUBLIC COUNTER IS CLOSED AND TELEPHONE CALLS WILL NO LONGER BE TAKEN AT HILLCREST HOUSE UNTIL FURTHER NOTICE The Office of the Traffic Commissioner is currently running an adapted service as all staff are currently working from home in line with Government guidance on Coronavirus (COVID-19). Most correspondence from the Office of the Traffic Commissioner will now be sent to you by email. There will be a reduction and possible delays on correspondence sent by post. The best way to reach us at the moment is digitally. Please upload documents through your VOL user account or email us. There may be delays if you send correspondence to us by post. At the moment we cannot be reached by phone. -

Audley Rural Parish Council 2011

AUDLEY RURAL PARISH COUNCIL 2011 – 2015 CONTACT DETAILS Councillor Name Address Telephone Email Ward Chair/Vice Chair AUDLEY WARD COUNCILLORS Mr D Cornes (Lib Dem) Audley House, 01782 720289 [email protected] Audley 30 Church St, Audley Staffs ST7 8DE Mrs V Pearson (Lib 23 Hill Terrace, 07946 862473 [email protected] Audley Vice Chair Dem) Audley, of Parish Staffs Council ST7 8DD Mrs B Kinnersley (Lib 22 Vernon Avenue, 01782 721864 [email protected] Audley Dem) Audley, Staffs ST7 8EF Mr P J Morgan (Lab) 115 Wereton Road, 01782 722523 [email protected] Audley Audley Staffs ST7 8HE BIGNALL END WARD COUNCILLORS Mrs C D Cornes (Lib Audley House, 01782 720289 [email protected] Bignall End Dem) 30 Church St, Audley Staffs ST7 8DE Mrs A Beech (Lab) Ley Ground Farm, m.07973119842 [email protected] Bignall End Bridgemere, Cheshire CW5 7PX 1 Councillor Name Address Telephone Email Ward Chair/Vice Chair Mr A Wemyss (Lib 18 Westfield Avenue, m.07810006001 [email protected]. Bignall End Dem) Audley, uk Staffs ST7 8EQ Mr H Proctor (Lib Rye Hills Farm, m.07900166169 [email protected] Bignall End Chair of Dem) Rye Hills, Parish Bignall End, Council Staffs ST7 8LP Mr M Dolman (Lib 14 Victoria St., 01782 563672 [email protected] Bignall End Dem) Chesterton, Newcastle, Staffs. ST5 7EW Mr P Warren (Lib 4 Wynbank Close, 01782 722830 Bignall End Dem) Miles Green, Staffs ST7 8LA HALMER END WARD COUNCILLORS Mr E Durber (Lib Dem) 16 Hill Terrace, 01782 729271 [email protected] Halmer End -

N C C Newc Coun Counc Jo Castle Ncil a Cil St Oint C E-Und Nd S Tatem

Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council and Stoke-on-Trent City Council Statement of Community Involvement Joint Consultation Report July 2015 Table of Contents Introduction Page 3 Regulations Page 3 Consultation Page 3 How was the consultation on Page 3 the Draft Joint SCI undertaken and who was consulted Main issues raised in Page 7 consultation responses on Draft Joint SCI Main changes made to the Page 8 Draft Joint SCI Appendices Page 12 Appendix 1 Copy of Joint Page 12 Press Release Appendix 2 Summary list of Page 14 who was consulted on the Draft SCI Appendix 3 Draft SCI Page 31 Consultation Response Form Appendix 4 Table of Page 36 Representations, officer response and proposed changes 2 Introduction This Joint Consultation Report sets out how the consultation on the Draft Newcastle-under- Lyme Borough Council and Stoke-on-Trent City Council Statement of Community Involvement (SCI) was undertaken, who was consulted, a summary of main issues raised in the consultation responses and a summary of how these issues have been considered. The SCI was adopted by Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council on the 15th July 2015 and by Stoke-on-Trent City Council on the 9th July 2015. Prior to adoption, Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council and Stoke-on-Trent City Council respective committees and Cabinets have considered the documents. Newcastle-under- Lyme Borough Council’s Planning Committee considered a report on the consultation responses and suggested changes to the SCI on the 3RD June 2015 and recommended a grammatical change at paragraph 2.9 (replacing the word which with who) and this was reported to DMPG on the 9th June 2015. -

Sir Gawain in the Moorlands of North Staffordshire, an Investigation

STRANGE COUNTRY: Sir Gawain in the moorlands of North Staffordshire, an investigation. by David Haden 2018 CONTENTS Timeline. 1. An overview of the previous work on Sir Gawain and North Staffordshire. 2. Sir Gawain’s possible routes into and through North Staffordshire. 3. Alton Castle as the castle of Bertilak of Hautdesert. 4. Who was William de Furnival, of Alton Castle? 5. The annual regional Minstrel Court at Tutbury. 6. “100 pieces of green silk, for the knights” at Tutbury. 7. The King’s Champion: William de Furnival’s friend in Parliament and a model for the Green Knight? 8. The nearby Cistercians at Croxden Abbey. 9. Wetton Mill and the Green Chapel: new evidence. 10. Two miles by mydmorn? 11. Some other local Gawain-poet candidates discounted. 12. “Here the Druids performed their rites”: some other poets of the district. 13. Tolkien and the Gawain country: the 1960s in Stoke-on-Trent. Appendix 1: A thrice ‘lifting and heaving’ folk practice in the Peak. Appendix 2: Some pictures of continental wild-men. Appendix 3: ‘A Bag of Giant Bones’: Erasmus Darwin and the district. Appendix 4: A letter to the Staffordshire Advertiser, 1870, and article in The Reliquary, 1870. (Full-text). Appendix 5: ‘Notes on the Explosions and Reports in Redhurst Gorge, and the Recent Exploration of Redhurst Cave’. (Full-text). Selected bibliography. Index. 1. An overview of the previous work on Sir Gawain and North Staffordshire. his chapter offers a short survey of the works which have, over the decades, associated Gawain with North T Staffordshire. I discuss them in order of appearance. -

North Housing Market Area Gypsy and Traveller Accommodation Needs Assessment : Final Report Brown, P, Scullion, LC and Niner, P

North housing market area Gypsy and Traveller accommodation needs assessment : Final report Brown, P, Scullion, LC and Niner, P Title North housing market area Gypsy and Traveller accommodation needs assessment : Final report Authors Brown, P, Scullion, LC and Niner, P Type Monograph URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/35864/ Published Date 2007 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. North Housing Market Area Gypsy and Traveller Accommodation Needs Assessment Final report Philip Brown and Lisa Hunt Salford Housing & Urban Studies Unit University of Salford Pat Niner Centre for Urban and Regional Studies University of Birmingham December 2007 2 About the Authors Philip Brown and Lisa Hunt are Research Fellows in the Salford Housing & Urban Studies Unit (SHUSU) at the University of Salford. Pat Niner is a Senior Lecturer in the Centre for Urban and Regional Studies (CURS) at the University of Birmingham The Salford Housing & Urban Studies Unit is a dedicated multi-disciplinary research and consultancy unit providing a range of services relating to housing and urban management to public and private sector clients. The Unit brings together researchers drawn from a range of disciplines including: social policy, housing management, urban geography, environmental management, psychology, social care and social work. -

E Newsletter

NORTH STAFFORDSHIRE FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY June Quarter 2016 EE NewNewslettesletterr ROGER JONES It is with great sadness to report the death of one of our members Mr Roger Jones on February 6th 2016. He will be greatly missed not only as a society member but also a friend of many. Roger and his wife Olwen attended regularly and our condolences go out to Olwen and family. We has a society have a number of genealogy projects that we would like some assistance with. can you spare a little time to help? This can be done in the comfort of your own home or at your local church or archive office. We are looking for volunteers who have a computer and can assist in the Staffordshire BMD’s project (which as helped us all at some time). Have you got a digital camera? We are looking for people who can take photographs of headstone so they can be transcribed. Have you got a collection of photographs of family graves, why not send they to us to transcribe? Have you got a story or an interesting article you would like to share? For more information please use the Email below. [email protected] STAFFORDSHIRE PEOPLE Sir Barnett Stross (25 December 1899 – 13 May 1967) Barnett Stross was born to a Jewish family, originally bearing the name Strasberg, in Poland on Christmas Day 1899. His parents Samuel and Cecilia, a Rabbi's daughter, were married in Poland in 1880. Barnett, called Bob by his family, had eleven siblings. When he was three, his family moved to Leeds.