PART II: MOVING THE FREIGHT

Chapter 5. Containerization, Intermodalism, and the Rise of the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach (10/05/05)

What one sees in a harbor is the concrete movement of goods. This movement can be explained in its totality only through recourse to abstraction. Marx tells us this, even if no one is listening anymore. If the stock market is the site in which the abstract character of money rules, the harbor is the site in which material goods appear in bulk, in the very flux of exchange. Use values slide by in the channel; the Ark is no longer a bestiary but an encyclopedia of trade and industry. This the reason for the antique mercantilist charm of harbors. But the more regularized, literally containerized, the movement of goods in harbors, that is, the more rationalized and automated, the more the harbor comes to resemble the stock market. A crucial phenomenological point here is the suppression of smell. Goods that once reeked—guano, gypsum, steamed tuna, hemp, molasses—now flow or are boxed. The boxes, viewed in vertical elevation, have the proportions of slightly elongated banknotes. The contents anonymous: electronic components, the worldly belongings of military dependents. Cocaine, scrap paper (who could know)? hidden behind the corrugated sheet steel walls emblazoned with the logos of the global shipping corporations: Evergreen, Matson, American President, Mitsui, Hanjin, Hyundai (Sekula 2002 p.12).

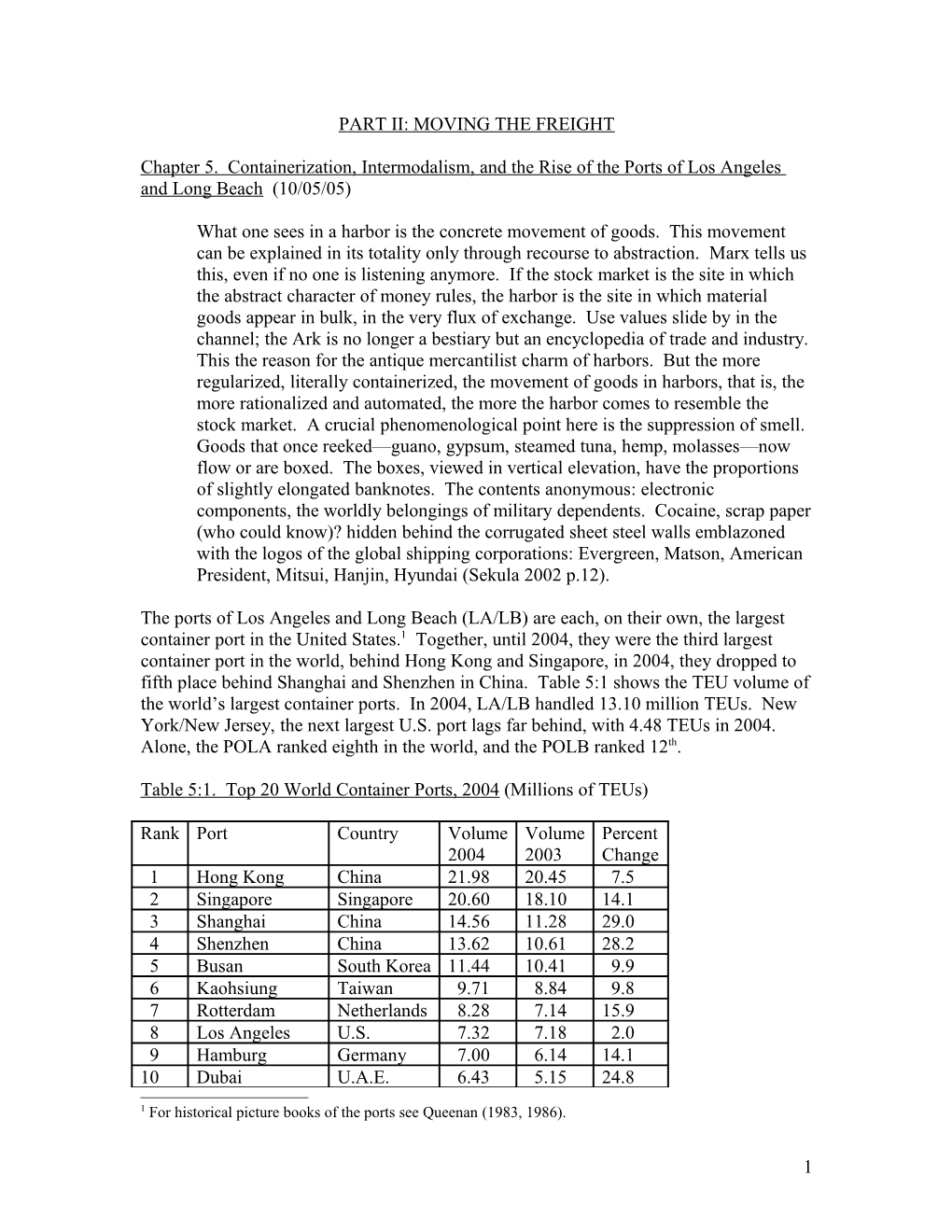

The ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach (LA/LB) are each, on their own, the largest container port in the United States.1 Together, until 2004, they were the third largest container port in the world, behind Hong Kong and Singapore, in 2004, they dropped to fifth place behind Shanghai and Shenzhen in China. Table 5:1 shows the TEU volume of the world’s largest container ports. In 2004, LA/LB handled 13.10 million TEUs. New York/New Jersey, the next largest U.S. port lags far behind, with 4.48 TEUs in 2004. Alone, the POLA ranked eighth in the world, and the POLB ranked 12th.

Table 5:1. Top 20 World Container Ports, 2004 (Millions of TEUs)

Rank Port Country Volume Volume Percent 2004 2003 Change 1 Hong Kong China 21.98 20.45 7.5 2 Singapore Singapore 20.60 18.10 14.1 3 Shanghai China 14.56 11.28 29.0 4 Shenzhen China 13.62 10.61 28.2 5 Busan South Korea 11.44 10.41 9.9 6 Kaohsiung Taiwan 9.71 8.84 9.8 7 Rotterdam Netherlands 8.28 7.14 15.9 8 Los Angeles U.S. 7.32 7.18 2.0 9 Hamburg Germany 7.00 6.14 14.1 10 Dubai U.A.E. 6.43 5.15 24.8

1 For historical picture books of the ports see Queenan (1983, 1986).

1 11 Antwerp Belgium 6.06 5.45 11.4 12 Long Beach U.S. 5.78 4.66 24.1 13 Port Kelang Malaysia 5.24 4.84 8.3 14 Qingdao China 5.14 4.24 21.3 15 New York/ U.S. 4.48 4.07 10.1 New Jersey 16 Tanjung Pelepas Malaysia 4.02 3.49 15.2 17 Ningbo China 4.01 2.76 44.5 18 Tianjin China 3.81 3.02 26.5 19 Laem Chabang Thailand 3.62 3.18 13.7 20 Tokyo Japan 3.58 3.31 8.0 Source: Journal of Commerce 8/15/05 pp.12A-14A.

The list presented in Table 5:1 is revealing in terms of the tremendous growth of the ports of China. Six of the top 20 are located in that country, whereas three (really two if we combine LA/LB) are in the United States. Overall, container ports demonstrated remarkable growth from 2003 to 2004. Of the top 50 such ports identified by the Journal of Commerce, 30 showed double-digit growth, and 13 had increases of more than 20 percent. Among the top 20, 14 showed double-digit growth and seven grew at a sizzling rate of over 20 percent in one year. The ports of LA/LB combined grew from 11.84 million TEUs in 2003 to 13.1 million in 2004.

The ports of LA/LB are not simply container ports. The POLB, which occupies 3,200 acres, has 32 cargo terminals, seven of which are container terminals. The others handle breakbulk items, including steel, scrap metal, fruit, lumber, building products, oil and petroleum products, chemicals, etc. Toyota has a terminal that handles automobiles. However, the seven container terminals are much bigger than the others (with the exception of Toyota), defining the port as primarily a container port.2 The POLA is similar. Occupying 7,500 acres, it has 27 cargo terminals, seven of which are container terminals. Its non-container facilities handle similar commodities. The port also offers recreational facilities and services cruise lines. Thus together the ports have 14 large container terminals (Southern California Ports Handbook, 2004-2005).

In 2002 the ports of LA/LB carried about $205 billion worth of imports and exports (Greenberg 2/10/03), handling 35 percent of all the waterborne container cargo in the U.S. (Calix 2002 p.3). The ports moved 164 million tons of freight in 2003. The main function of the LA/LB ports is the importing of containers filled primarily with manufactured products from Asia. The ports of LA/LB represent the premier gateway to the United States for Asian production.

In this chapter we briefly examine the development of containerization and how it has revolutionized freight movement. We consider how this opened up the prospect for major advances in intermodal freight transportation, and how a legal environment had to be created to support these advances. Next, we briefly look at the governance structure

2 Hall (2002) discusses how the POLB became specialized as a container port, leading to the exclusion of automobile terminals which shifted to smaller ports such as San Diego and Hueneme.

2 of container ports, and at how the rise of intermodalism affected ports in general. We then examine the ports of LA/LB and their spectacular growth over the last few decades, attempting to explain why, of all the West Coast ports, Southern California has emerged as the major port complex. We end the chapter by considering whether this dominance is likely to endure, first by examining local community resistance to expansion of the ports, and second, by exploring the alternatives to LA/LB and their prospects.

Containerization and Intermodalism

Containerization

Before containerization (also known as a form of unitization), the ocean transportation of freight generally depended on the break-bulk method. Packages were loaded on pallets, which were hoisted in a cargo net by crane onto the ship. Longshore workers in the hold of the ship would carefully stow the cargo to protect it from damage, a lengthy and labor- intensive process. The cargo would have to be unloaded (discharged) in the same manner at the other end of the voyage, making ocean freight transportation a long and costly process (Campbell 1993; Chilcote 1988; DeBoer and Kaufman 2002; Talley 2000).

Containerization has revolutionized this system. It seems safe to say that containerization was a prerequisite to global production, and that, without it, globalization would have been immensely slowed down. Containerization allowed for a vast increase in the speed with which cargo could be moved from one corner of the earth to another. It was an essential ingredient for the logistics revolution that we discussed in Chapter 2. As Campbell (1993 p.217) states: “Flexible specialization requires a massive, highly standardized distribution system to link markets and producers.”

Malcolm McLean, owner of a trucking company, is the individual who is credited with first developing the concept of containers, in 1955. He realized that truck trailers could be filled and shipped without their contents ever having to be handled between point of origin and point of destination. The wheels of the trailers could be detachable so that the trailer boxes could be stacked and chassis with wheels could be attached or removed as needed. McLean purchased a small tanker company, which he named Sea-Land, and adapted it for this purpose. The first voyage, between Newark and Puerto Rico, took place in 1956. The first international voyage, to Rotterdam, occurred in 1966, a date that can be viewed as the start of containerization in international trade (Chilcote 1988 pp.126-7; Muller 1999 Chapter 3; Talley 2000 p.933).

Containerization was pushed mainly by the steamship companies rather than the ports (Campbell 1993 p.215). Needless to say, it took some time for the idea to catch on, and for costly infrastructure to be put into place that would make containerization practical. Standardizations of various sorts had to be agreed upon. Ports had to invest billions of dollars in new equipment and terminal designs (DeBoer and Kaufman 2002 p.33). Ships needed to be developed that could carry containers safely. Railroads had to develop adaptations. Nevertheless, the conversion was fairly rapid, given how much expense was involved. The truth is that without massive participation, the transformation could not

3 have occurred, since container ships could only dock at ports that could handle them, and ports would only invest if they had sufficient traffic to justify it (Campbell 1993 p.218).

Standardized containers are generally 8 feet in width, 8 feet 6 inches in height, and 20, 40 or 45 feet long. Taller containers, known as high cubes, are also available, with a height of 9 feet 6 inches. The standard measure for number of containers is TEUs (20 foot equivalent units), even though 40 foot containers (FEUs) are far more common, presumably to avoid fractions in the counting system. Containers have locking mechanisms on their corners so that they can be secured to cranes, to truck chassis, to rail cars, and to each other for stacking (Chilcote 1988 p.126; Talley 2000 p.933).

Containerization revolutionized ports and the way they handle freight. Large gantry cranes (able to move side to side) now lift the containers from the dock into a ship with slots to hold them in place, and they can also be stacked high on deck. The cranes are designed to carry multi-ton containers. The average weight per TEU is generally estimated at 17 tons, so a 40 foot container would average around 34 tons. Mechanization greatly increased the speed with which ships could be loaded and unloaded, dramatically raising the productivity of labor and the ship. It is estimated that productivity increased at least 5 to 10 times. Instead of spending half of its time in port, a container vessel could reduce that amount to 10-20 percent (Chilcote 1988 pp.127-130). Whereas it often took a week to unload and load a break-bulk ship, a containership could be in port for one or two days (Talley 2000).

During the break-bulk era, the logic of shipping was to keep ships relatively small, making loading and unloading quicker and easier. To increase service, more ships would be added, and more ports visited. By reducing the costs of loading and unloading, containerization changed the logic of shipping. It does not take substantially longer to load and unload a larger container vessel than a smaller one since additional cranes can be used alongside the ship. It now pays to have bigger and bigger ships. By the end of the 1970s, the largest container ships were already four times larger than the largest break-bulk ships (Chilcote 1988 p.131). And the size has continued to climb in each decade, with no end in sight. At the end of 2003 the ports of LA/LB were preparing for at least three strings of 8,000 plus TEU vessels. Apparently 84 such ships were on order at shipyards, and China Shipping was ordering eight 9,500 TEU vessels. As can be imagined, these giants require some adjustments on the part of the ports (Mongelluzzo 11/17/03). To give a sense of the size of these vessels, the first to call was the OOCL Long Beach, which is 1,056 feet long (nearly the length of four football fields) and 140 feet wide (enough for 17 containers across).

Containerization favored large shippers (importers and exporters) over smaller ones, in comparison with break-bulk shipping. The advantage of shipping full containers was enormous. LCL (less-than-container load) requires consolidation of smaller loads, which in turn requires intermediaries of various types who take their cut (Campbell 1993 p.218). This advantage has surely benefited the giant retailers, who are able to use their massive volumes to gain all kinds of benefits, including lower rates.

4 Landbridge

The Panama Canal, which was the typical route for goods from Asia to be shipped to the U.S. East Coast, can handle vessels of 3,000-3,500 TEUs and possibly, with redesign, a maximum of 4,400 TEUs. Needless to say, this size limitation contradicts the economic advantages of larger container ships, known as post-panamax vessels. Post-panamax vessels were made possible by the development of landbridge or the movement of goods from ships to the railroads and across the United States on dry land. Landbridge most accurately refers to moving goods across the entire U.S. land mass and on to other ships on the opposite coast for shipment to Europe or elsewhere. Mini-landbridge refers to movements where the containers are unloaded from rail on the Coast and make no further ocean voyages. Micro-landbridge refers to rail movements that end somewhere within U.S. territory. Following Chadwin, Pope and Talley (1990) we use the simpler term landbridge to refer to all of these types of move.

Landbridge was first developed by a company called Seatrain, to move European cargo from New York to California, avoiding the Panama Canal and saving a week in transit time. However, the system works even better from West to East, mainly because of the huge and growing volume of Asian imports. The trans-Pacific shipping lines did not need extra vessels, and found that their costs were not greatly increased by providing shippers with landbridge service. They led the way in working with the railroads. By the late 1970s, half of the trans-Pacific traffic from Asia to the Eastern U.S. was moving by landbridge (Chilcote 1988 pp.137-8). The first post-panamax ship involved in the trans- Pacific trade was developed by the steamship company APL (American Presidents Line), and arrived on the West Coast in 1988.

International Intermodalism

Landbridge is a critical component of international intermodal freight transportation (Muller 1999 Chapter 6). Containerization allowed boxes to be moved from ships either directly to trains, or to be delivered to railheads by port truckers. Although trucking companies also play a critical role in intermodal moves across the nation, the basic units of the port intermodal system are: steamship lines, port truckers, and railroads. Indeed, in the industry, when people refer to intermodal transportation, they mean putting the freight on rail. Of course, the term has much wider application, including shifts between any two modes of transportation.

According to DeBoer and Kaufman (2002 p.33):

[Containerization] forces a much closer relationship between steamship companies, ports, railroads, and truckers. Where once each mode and each port had its clearly defined “silo mission,” the container tended to blur everyone’s mission. Whereas steamship companies used to worry only about getting cargo from port to port, many now provide door-to-door movement of cargo. Where once each mode owned its own equipment, now ownership of containers, railcars, and highway tractors can be vested in any mode.

5 International intermodalism allowed for the movement of cargo door-to-door on a single bill of lading. One transportation entity could take charge of the entire move, from factory in Asia to warehouse in the United States. This simplified trade enormously, making it much easier for shippers to import goods. The various types of carriers had to cooperate in order to provide continuous, seamless, reliable freight movement. Door-to- door service has sometimes also been used for more sophisticated just-in-time delivery. The evolution of information technology abetted the process (Shashikumar and Schatz 2000).

The development of intermodalism and landbridge gave a tremendous boost to all of the West Coast ports, especially those of Southern California. According to Chilcote (1988 p.134):

If cargo-handling productivity gain was the original impetus for a ship owner to convert to a container operation, the second aspect of the containership, ease of conveyance between transport modes, became even more important. On the West Coast, a fast-growing trade opportunity related to the railroads was developing. Asian trade was increasingly being diverted from the Panama Canal route and being routed on to the eastern United States by rail. Shippers had found that rail transport to points across the continent from West Coast ports could be economically advantageous. The combined Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach subsequently became the largest container load center on the coast…partly owing to their enormous local market and partly to intermodalism.

The Legal Basis of International Intermodalism

The development of international intermodal transportation was held up by the U.S. government for a period for complicated reasons, including the fact that the steamship lines were unregulated by the government and benefited from anti-trust immunity, permitting them to form rate-setting conferences (a topic we shall cover in the next chapter) (Shashikumar and Schatz 2000).

Towards the end of the 1970s all of the transportation modes were deregulated. The Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act was passed in 1976, followed by the Staggers Rail Act in 1980. The Motor Carrier Act of 1980 deregulated the trucking industry. These changes set the stage for permitting international intermodalism to develop. The culmination of this process was the passage of the U.S. Shipping Act in 1984 (Shashikumar and Schatz 2000; Talley 2000).

Prior to the 1984 Shipping Act, the regulation of the railroads by the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) and of the steamship lines by the Federal Maritime Commission (FMC) built walls between the two modes of transportation. The 1984 Act allowed the steamship lines to enter into agreements about rates with the railroads, enabling them to offer customers through-transportation, or door-to-door service (DeBoer and Kaufman

6 2002). Other legislation lifted barriers against trucking companies acquiring railroads and vice versa (Shashikumar and Schatz 2000).

Intermodalism has expanded since 1984. Many steamship lines now offer more services than the basic door-to-door delivery. These include documentation, cargo clearance, warehousing, product assembly, distribution, etc. Most of the biggest liner companies have their own logistics subsidiaries which provide a host of such services (Shashikumar and Schatz 2000).

Changes to Ports

Port Governance

Steven Erie (2004) has studied the governance of the ports of LA/LB in some detail. He points out that, unlike most U.S. ports, which are run by regional public authorities, the city of Los Angeles, operating at the municipal level, and followed by another municipality, Long Beach, created a powerful proprietary (semi-autonomous), department to run its harbor. The Southern California port authorities, unlike those of NY/NJ, for example, serve under the nominal control of their mayors and city councils, but are, in practice, able to behave as developmental government actors who can pursue a growth agenda with limited interference. The ports act as bureaucratic agencies with considerable “political autonomy and transformative capacity” (Erie 2004 pp.29-32; p.34).

The cities interface with the ports through city-appointed Boards of Harbor Commissioners, who in turn appoint administrations which run the daily affairs of the ports. But the cities have little direct authority over the ports’ budgets and capital investments. Their funds are generally shielded from raids by the cities.3 The ports act as “public enterprises,” behaving more or less like private, profit-making corporations. The ideology of the ports’ managers and bureaucrats is consistent with a private enterprise answerable to its stockholders (Gulick 2001 pp.164-5; Erie 2004 pp.34-39; Hall 2002).4

The basic function of the port authorities is to develop the built environment. Gulick (2001 pp.164-5) describes them as functioning like urban growth machines. That is, their major purpose is to increase the number of TEUs that flow through their facilities by attracting as many shipping companies as possible to use them. In turn they provide the companies with equipment, infrastructure, and services. The California ports serve primarily as landlords and are described as “landlord ports.” They buy cargo-handling equipment, finance the construction of marine terminals, build intermodal facilities, and lease this developed space to the steamship lines, terminal operators, and railroads. They

3 An important exception occurred for the POLA in the 1990s when the city of Los Angeles laid claim to some port revenues (Erie 2004 pp.124-129). The city was sued by the Steamship Association of Southern California. The SASC won, and the city had to stop raiding port coffers. 4 One can look at this from different perspectives. Erie (2004) sees this in a positive light as an opportunity for unrestricted development for the entire region. Gulick (2001) and Hall (2002) both view it more critically, looking more at the costs of such development.

7 collect rent for the use of these facilities, as well as collecting wharfage (an assessment per ton of cargo), and dockage (a fee for the amount of time a ship is in berth) (Gulick 2001 pp.169-170).

Here is the way the POLB describes itself:

The Port of Long Beach is not responsible for ordering cargo or shipping cargo. We operate as a landlord and lease property to shipping lines from around the world. Shippers—such as manufacturers, large department stores and other retailers—book space with these shipping lines to move imports into the United States. This cargo is then unloaded at the Port of Long Beach to meet the demands of local consumers, as well as consumers throughout the United States (POLB 2004 p.1).

The quarterly newsletter from which this quote is taken also points out that the port land was transferred to the city by the State of California for the purpose of developing and maintaining a municipal harbor. The port’s employees are city employees. However, the port does not depend on tax dollars for its support, generating its own revenues from leases, which pay for employee salaries and benefits, maintenance of the terminals, and repayment of debt for capital improvements. The POLB employs 350 people, but is not involved in the employment of longshore workers, who are hired by the terminal operators (POLB 2004 p.2). The same principles apply to the POLA.

A key feature of ports is that they are fixed in space, whereas their customers are mobile. The mobility of the steamship lines (as well as of the importers and exporters, who can switch ports by switching carriers) puts the ports in competition with each other to lure customers/tenants. LA and LB are in competition with each other, though they have also cooperated over major infrastructure projects.

The Impact of Intermodalism on Competiton between Ports

A number of authors (e.g., Boschken 1988, Campbell 1993, Chilcote 1988, Corbett 1996, Dowd 1988, Hall 2002, Luberoff and Walder 2000, Slack 1993, Talley 2000) have pointed out that the rise of intermodalism has disempowered ports. Before the takeover of containerization, ports had natural hinterlands, which ensured the flow of trade through them. With intermodalism, marine containers can be hauled anywhere by truck or train for a reasonable price, and do not depend on arrival at a particular port. Even major regions, such as the East Coast versus the West Coast, are placed in competition with each other.

Given the expense of port visits, the steamship lines (like the airlines) prefer to operate on a hub and spoke system. Put another way, they want their ever bigger containerships, which require heavy investment, to maximize their returns by making as many trips across the Pacific as possible. It is more economical to stop at fewer ports—usually two or even only one on the West Coast. This increases the competition between ports, which have invested in very expensive container terminals in the hopes of drawing liner trade.

8 The result has been the development of overcapacity among the ports, and investments that may not pay off. Power shifted from the ports to the steamship lines, since the latter could choose which ports they would call at based on other criteria than natural hinterland. Thus there is a tendency for concentration to develop in the ports system, as the big get bigger, and the small diminish (Chilcote 1988, Gulick 2001 Chapter 3). This process does not determine which ports will succeed, but it does determine that some (like LA/LB, as it turns out) will be extraordinarily successful.

Before containerization and intermodalism, the primary customers of the ports used to be the shippers, i.e. the importers and exporters. Door-to-door service changed that. It meant that the shippers had less interest in which port was selected. Their major concern was inexpensive and timely delivery and, once door-to-door service was offered, it was up to the steamship lines to decide which the most efficient ports for discharging cargo were. The primary customers of the ports thus became the steamship lines.

Port costs are a small percentage of the total cost of buying and running ships, which means that, in the competition between ports, offering price incentives may not be a viable option. The steamship companies have other priorities in choosing their ports of call. Moreover, with transportation deregulation, public and standardized rates have disappeared, leaving the ability of shippers to introduce such factors as volume into the rates—factors which the ports cannot control. This adds to the vulnerability of the ports, which must compete for steamship liner service (Campbell 1993; Dowd 1988, p.230-1).

Intermodalism changes the nature of port investment. Ports used to invest mainly for the benefit of their region. Now they are being asked to invest for the benefit of the entire country (DeBoer and Kaufman 2002 p.34), without the security of knowing that the investment will pay off. Even if successful, the regions that are close to the ports may have to bear additional costs, on top of the financial ones, such as congestion and pollution. The contradiction between national benefit and local cost has become a serious problem, a topic to which we shall return (Campbell 1993 pp.223-5; Erie 2004).

The Ports of LA/LB

Southern California Exceptionalism?

The twin ports of Southern California appear to be an exception to the general pattern of competition between U.S. ports. According to Dowd (1988, p.26):

Only a few Ports in the country can ignore these competitive pressures. For instance, there are a lot of goods going directly into the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, even though Port costs are higher, because that is where the major market is. And that is why they are consistently earning more money than everybody else—they have a monopoly on a lot of cargo… Long Beach and Los Angeles can set their rates, and have, in fact, set their rates, to provide a very good profit for themselves. This type of situation probably only exists at one other place, and that is the Port of New York/New Jersey.

9 Until recently, the ports of LA/LB have been able to avoid the pitfalls of competition for all the reasons mentioned above. Indeed, the LA/LB ports have had a kind of arrogance about them, feeling that they can get away with almost anything because they have such a hot product. As Dowd notes, these ports are known for being expensive, but it does not matter—the attractions are too strong. Of course, there is no guarantee that this popularity will last (as we shall see below), and undoubtedly there are steamship lines and major shippers who would like to see it changed.

The Size and Importance of the Ports

As we stated at the beginning of this chapter, the ports of LA/LB comprise the largest container port complex in the United States. Our opening statistics looked at overall trade, including both imports and exports. However, if we focus just on imports, the ports of LA/LB stand out even more. In the year 2000, as shown in Table 5:2, together they accounted for 43.8 percent of imported containers to the top ten U.S container ports. The next largest port complex, New York-New Jersey, was a distant second with 14.6 percent of total imports. The other major West Coast ports, Seattle-Tacoma and Oakland, did not even crack double digits. It is safe to conclude that over 40 percent of the entire nation’s containerized trade passes through the ports of LA/LB.

Table 5:2. Top 10 U.S. Ports by Number of U.S-Bound Containers, 2000

U.S. Ports Imports (TEUs) Percent Los Angeles 1,774,000 24.7% Long Beach 1,371,000 19.1 New York-New Jersey 1,044,000 14.6 Charleston 376,000 5.2 Savannah 312,000 4.3 Norfolk 306,000 4.3 Seattle 284,000 4.0 Tacoma 273,000 3.8 Oakland 268,000 3.7 Houston 233,000 3.3 Total (top 10) 6,241,000 87.0 Source: U.S. GAO (2003) based on PIERS data.

Note that we are focusing on container ports, as opposed to ports in general. Some U.S. ports specialize in bulk products, such as oil, and the tonnage they move may be greater than the tonnage of LA/LB. The unique feature of containers is that they carry higher value products.

LA/LB was not always the leading port complex of the United States. New York was the most significant port for most of U.S. history. The shift occurred in the mid-1980s. Table 5:3 compares the number of TEUs handled by the two port complexes for the years 1984-1992. As can be seen, LA/LB passed NY/NJ in 1986, and continued growing at a

10 steady clip, whereas NY/NJ dropped and then recouped somewhat in terms of container traffic. By 1992, LA/LB had about double the container volume of NY/NJ.

Table 5:3. Comparison of Containerized Traffic of the Ports of NY/NJ and LA/LB, 1984-1992 (000 TEUs)

Year NY/NJ LA/LB 1984 2,255 2,049 1985 2,367 2,277 1986 2,340 2,719 1987 2,089 3,040 1988 2,096 3,192 1989 1,988 3,102 1990 1,872 3,709 1991 1,865 3,806 1992 2,104 4,118 Source: Rimmer (1998), p.443.

In the 1990s, in particular, trade through the ports of LA/LB began to grow at a rapid rate, and, despite some recessional blips, has shown a continual upward movement. The volume of containerized cargo passing through the two ports doubled during the decade. Some predict that trade volumes through the ports will double again by 2010, and treble by 2020 to the equivalent of 24.3 million TEUs per year (Mercer 1998).

Table 5:4 shows growth of TEUs through the ports from 1993-2003. Despite the recession of 2001-2, the number of TEUs continued to grow for the ports together. Long Beach showed decline, but LA made up for it. The Table shows how LA and Long Beach have exchanged leadership positions over the years, but there were signs in 2004 that Long Beach was bouncing back, as we shall see (Greenberg 7/19/04).

Table 5:4. Growth in Containerized Traffic Through the Ports of LA/LB, 1993-2003 (000 TEUs)

Year LA LB LA/LB 1993 1,626 1,543 3,169 1994 1,789 1,935 3,724 1995 1,869 2,116 3,985 1996 1,890 2,325 4,215 1997 2,092 2,667 4,759 1998 2,292 2,879 5,157 1999 2,557 3,051 5,608 2000 3,233 3,271 6,504 2001 3,408 3,213 6,621 2002 4,043 3,208 7,251 2003 4,709 3,114 7,823

11 2004 4,897 3,715 8,612 Kyser 2005 p.19.

It is important to recognize that the Southern California ports are especially strong in imports. The exports flowing through the ports are low, leading to a problem of imbalance. One of the major exports is “air” or “smog,” i.e. empty containers that are sent back to Asia to be refilled. These are usually left out of TEU statistics, but they still need to be handled by the ports and loaded on to vessels.

The West Coast Ports

There are 27 ports on the West Coast. Washington state has 10, including small ones like Port Angeles and Everett. The major ports of the state are Seattle and Tacoma. Oregon has three ports, with Portland as the most significant. California has 14 ports, 10 of which are in Northern California. For example, Stockton and Redwood City each have small ports. The largest port in the region is Oakland. The four ports in Southern California include LA/LB, San Diego and Port Hueneme. Thus, six of the ports account for the bulk of the traffic: Seattle, Tacoma, Portland, Oakland, Los Angeles, and Long Beach.

The rise in containerized traffic through the West Coast ports, as a whole, is dramatic. In 1970, the West Coast ports moved 8.8 million tons of container traffic. This figure rose to 35.0 million tons in 1980, 90.3 million tons in 1990, and 174.0 million tons in 2000. By 2004 it had risen to 221.5 million tons.5 Containerized cargo also grew as a percentage of total tonnage handled by the ports. In 1970 it accounted for 14.6 percent, in 1980, 30.8 percent, in 1990, 49.7 percent, and in 2000, 67.0 percent. By 2004 the figure reached 70.5 percent. All other forms of cargo, including general cargo (break bulk), bulk cargo, lumber and logs, and autos and trucks, either remained stable, declined, or grew a small amount, whereas containerized cargo shows almost a straight line of upward growth (PMA 2004 p.55).

In terms of numbers of containers, in 1972, the West Coast ports handled 12.4 million TEUs. By 1980 the number had grown to 34.96 million TEUs. The year 1990 showed a leap to 90.3 million, and 2000 to 174.0 million TEUs. In 2004 the number of TEUs handled by these ports stood at 221.5 million TEUs (PMA 2004 p.55). It is clear that containerized trade through the West Coast ports has grown hugely over the last three decades, and shows no signs of abating.

The principal reason for the rise of the West Coast ports is the rise in U.S. trade with Asia. Prior to 1978, Europe was the United States’ primary trading partner. In that year, Asia took over (Gulick 1998, p.62). As Asian countries developed into manufacturing power-houses, with a focus on producing goods for export, the West Coast ports became the nearest points of entry. Most important to this trade is the rise of China. In the 12

5 Beginning in 1984, containerized cargo was no longer reported in terms of tonnage but TEUs. To calculate tonnage, the number of TEUs was multiplied by 17 on the assumption that the average TEU weighs 17 tons (PMA 2004 p.55).

12 month period May 2004-April 2005, the proportion of Asian-origin TEUs that came from China to the West Coast ports was 57.4 percent. Hong Kong added another 9.3 percent, meaning that about 2/3 of West Coast containerized trade was with China. Next in line was Japan with a mere 8 percent. Moreover, China’s TEU volume to the West Coast ports grew 24.9 percent from the previous year (Mongelluzzo 7/4/05 p.18).

The U.S. economy has experienced a major shift in terms of manufacturing. The eastern and mid-western states used to be industrial centers, and the major flow of manufactured goods was from East to West. Indeed, this created back-flow problems for transportation providers who could not find enough cargo for shipments from West to East. Now, with the rise of manufactured imports from Asia, the flows have been reversed. Manufactured goods arrive at West Coast ports, many of which are shipped East. The back-flow problem has shifted direction, as fewer goods move from East to West than from West to East (Calix 2002 p.4).

Table 5:5 shows the distribution of containerized traffic through the major West Coast ports, as well as the smaller West Coast ports combined, from 2000 to 2004. It is clearly evident that the ports of LA/LB dominate containerized trade on the West Coast, accounting now for almost 70 percent of this traffic. True, there was a period when the POLA took off faster than the POLB, but that may be changing, as shown in the figures for 2004.

Table 5:5. Percentage Distribution of Containerized Cargo Handled by West Coast Ports

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 LB 33.6 33.1 30.2 26.3 29.2 LA 33.2 36.1 39.2 42.9 39.8 LA/LB 66.8 69.2 69.4 69.2 69.0 Oakland 11.6 11.1 10.6 10.6 10.7 Portland 2.1 2.1 1.7 1.8 1.6 Tacoma 8.8 8.6 9.1 9.6 9.2 Seattle 10.2 8.7 8.8 8.0 8.8 All Others 0.5 0.4 0.4 0.7 0.7 Total (TEUs) 10,237,519 10,101,589 10,823,054 11,922,794 13,029,661 Source: PMA 2003 p.56.

The importance of the Southern California ports has increased since the mid-1990s. In 1995, the LA/LB ports together accounted for 57.5 percent of container throughput (imports and exports) on the West Coast (Gulick 1998). By 1998 that percent had climbed to 63.7. As the Table shows, the numbers of TEUs handled by the West Coast ports continues to grow, so that the relative stability of LA/LB’s percentage over the last four years means that the Southern California ports kept up with this growth.

As we have mentioned, because of the discrepancy between East and Westbound trade across the Pacific, empty containers get sent back to Asia. In 2004, the West Coast

13 “exported” 5,530,797 empty TEUs. Cargo-bearing TEUs numbered 13,258,233,6 for a total pf 18,789,030 TEUs actually handled by the ports, 28.9 percent of which were empties. LA/LB had a slightly higher percentage of empties than the coast as a whole, with 30.1 percent empties (PMA 2004 p.54).

In terms of imports only, the discrepancy in containerized traffic among the West Coast ports is even starker. According to the Journal of Commerce (3/3/03), in 2002, the ports of LA/LB dealt with a whopping 80 percent of all West Coast imports in the trans- Pacific trade. For example, 60 percent of the goods imported to Chicago come through the ports of LA/LB. (Calix 2002 pp.3-4).

Explaining the Rise of the Ports of LA/LB

There are a number of reasons for the rise of the ports of LA/LB relative to the other West Coast ports. These can be divided as follows: size of local market, geographical location, infrastructural investments and advantages, and development of support services. Let us consider each of these in turn. a. Size of Local Market

Compared to the other West Coast ports, the ports of LA/LB have the tremendous advantage of being located in a major population center. The Southern California six- county region of Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, Imperial and Ventura, has a population of almost 17 million people (more than the state of Florida), and produced goods and services worth over $600 billion in 2000, almost half of the state’s total of $1.3 trillion. If California were considered as a country, it would rank fifth in the world in terms of GDP, after the United Kingdom and before France, and the six-county Southern California region would rank tenth, just behind Brazil (Calix 2002; Ibold 6/18/01; Robinson-Jacobs 6/14/01). A significant proportion of the goods that enter through the ports—some say as high as 50 percent—stays in the region (a point we shall revisit in later chapters).

Calix (2002 p.2) describes the emergence of Southern California as the distribution center for U.S.-Pacific Rim trade as follows:

The massive internal market draws trade both for final consumption and for inputs in value-added products… These two factors… drive up the percentage of international cargo that makes its first stop in Southern California. With so much cargo destined here in the first place, it makes sense for shippers to use the region as a distribution center for the rest of the United States.

The fact that Southern California is a major manufacturing center, competing with Chicago for the largest number of manufacturing employees in the nation, contributes to its ability to provide value-added inputs.

6 Why this figure differs slightly from the figure presented in Table 5.5 we cannot say.

14 The attraction of the Southern California ports is demonstrated by the tale of one shipper, Hasbro Toys. Hasbro recently moved its distribution center (DC) from Seattle to Southern California (Mongelluzzo 6/17/02)7 Hasbro imports about 17,500 TEUs a year. It had an arrangement with the port of Seattle to occupy a port-owned distribution facility on the waterfront. This was a very advantageous arrangement for the company: it avoided truck hauls to transloading facilities, and received discounts on ocean freight rates because the steamship lines got the containers back right away and did not have to haul them back from the eastern part of the country. Moreover, Seattle is at least a day closer to Asia than Southern California, and is less congested.

But in June 2002, Hasbro opened a DC in Ontario in the Inland Empire, shifting to the ports of LA/LB as its main port of entry. Why did Hasbro move? The company decided that it could save money if it consolidated all its distribution functions in one facility. And deciding to locate that facility in Southern California rested, in large measure, on the size of the local market. Not only could Hasbro take advantage of shipping to the closer LA market, but when goods are sent to the East, it is easier to fill domestic containers and trailers for the backhaul because more goods moving from East to West are destined for Southern California. b. Geographic Location

The distance between Asian countries and the West Coast of the U.S. favors the Pacific Northwest ports of Seattle and Tacoma. They are at least one day closer to East and Southeast Asia than is California, especially Southern California. So this again raises the question of why LA/LB became the premier gateway. Perhaps the size of the local market, and infrastructural developments that will be discussed in the next section explain it completely. Yet we believe another kind of geographic factor plays a role, apart from sheer distance. This is the fact that LA/LB is at the bottom end of the U.S. West Coast string of major ports. If a ship is only going to stop at two West Coast ports, one of those is likely to be in the North and the other in the South. The most prevalent pattern is for ships from Asia to discharge first in LA/LB, with some loading, then move up the coast to one other port for further discharging and more loading, and then head off back to Asia.

Asian exporting countries can be divided along a North-South axis. The Pacific Northwest ports are all closer to Asia, but the South Asian ports, including those of China, are relatively closer to Southern California than are the North Asian ports. The rise of China and the relative decline of Japan as export powers is thus linked to the rise of LA/LB relative to Seattle/ Tacoma (Gulick 1998). Everything points to the continuation of this basic geographic advantage of the Southern California ports.

One port official told us that the preeminent shipping lane in the world is Hong Kong to LA/LB non-stop. Hong Kong, he noted, like Singapore, is a through port. Both of them serve as hubs for production that occurs elsewhere. The steamship line, China Shipping, was planning to dedicate its largest TEU ships to the Hong Kong-LA/LB lane. “This is

7 The story presented here is based entirely on Mongelluzzo’s story in the Journal of Commerce.

15 the biggest focal point for us,” said the port official. “Hong Kong is our Mecca. South China is the heart of our trade.” Another port official (Wylie 2003) put it this way: “SoCal ports are perfectly situated between the fastest growing economy in the world (China) and the largest consuming market in the world (U.S.).” c. Infrastructure

In terms of infrastructure, the ports of LA/LB benefit from deep water channels, and access to roads and railroads that provide good connections to the rest of the country (a topic we shall consider more in Chapter 7 when we turn to land-based transportation). Two Class I railroads, the Union Pacific (UP) and the Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) both provide service from the ports to the eastern part of the country. In addition, the region is richly endowed with Interstate highways, including roads that lead north to cover the Western region, as well as roads that lead east.

The state of California also has also played a role in the prominence of the ports of LA/LB. California has coastal protection policies that have prohibited new development along the coastline. These policies have encouraged the expansion of existing ports rather than the creation of new ones (Wylie 2003). LA/LB have benefited from this forced concentration.

However, critical to the development of the Southern California ports, and the creation of Los Angeles as the premier gateway for trade with Asia, was the system of governance of both of the ports, and their resulting ability to invest wholeheartedly in infrastructure, without too much interference (Erie 2004). In other words, the success of these ports is, in part, a product of entrepreneurship and a government system that allowed public bureaucrats to act maximally as though they were business enterprises, while taking advantage of public ability to raise the capital to do so. The latest example is the construction of the Alameda Corridor, based on a public-private partnership, a project that will be considered in Chapter 7. The Los Angeles waterfront had few natural advantages. It took human intervention to transform the ports into the magnificent facilities that they have become.

Gulick (1998) also makes the point that ports can be active in creating regional development alliances that generate support for port investment and minimize the likelihood of opposition by social activists, including environmentalists, who are concerned about the negative local impact of port expansion—a topic that has boiled to the surface in Los Angeles recently. The Southern California port authorities have certainly been active in pursuing their competitive advantage through investing and political engagement. Nevertheless, their geographical advantage, given the changes brought about by containerization and intermodalism, and the benefits of their large local market, give them a leg up that almost no investment by other ports could match. d. Support Services

16 Once the ports established themselves as key gateways, various logistics services were attracted to the area. Thus warehousing is available in the South Bay, and in the nearby Inland Empire. Major corporations have come to Southern California to set up their regional distribution centers (DCs), in large part to have access to the ports. In addition, numerous other companies providing services to the ports and their users have set themselves up. These include customs brokers, freight forwarders, NVOCCs (non-vessel operating common carriers), container freight stations, transloading operations, harbor drayage companies, cold storage facilities, export packaging companies, and logistics providers of all kinds.

A synergy has developed between the growth of the ports and the growth of these kinds of services. The services have developed because of the ports, but the customers of the ports are attracted to them, in part, because of the ready availability of these services. The interdependence feeds the growth of both the ports and the services in an interactive spiral of growth. One can describe the ports and their surroundings as a special kind of industrial district, one geared to the process of international trade.

The connection between the ports and available logistics services is evolving. For example, according to Mongelluzzo (6/17/02), another factor favoring LA/LB is a shift in how Asian imports are being handled:

When it comes to intermodal through moves along the northern route, where full containers are transferred from a vessel to a double-stack train for shipment to Chicago or New York, the Pacific Northwest is an ideal gateway because of its closer proximity to Asia on the great circle shipping routes. But when the importer chooses to unload the marine containers and consolidate contents with other products for movement by truck—as is increasingly the case—Seattle and Tacoma lose their natural advantages. Land, labor and a concentration of 3PLs [third-party logistics companies] that perform value-added services to imported goods, such as making them store-ready, are making Southern California into a dense hub for logistics services that builds on itself by attracting additional cargo and carriers.

The advantage of transloading ocean containers near the ports and putting the cargo into domestic containers and trailers lies, in part, in the ability to put empty containers back on the ships and send them right back to Asia. If they get sent across the country, it is easy for the maritime containers to get stuck somewhere in the Mid-west, without loads to bring back to the West Coast. Repositioning these empties is an expensive proposition.

The Future of the Ports of LA/LB? 8

8 Erie (2004 Chapter 5) deals with a number of threats to the ports of LA/LB, including revenue diversion by the cities, environmental policy challenges, and secession movement by the L.A. harbor communities of San Pedro and Wilmington. Because he deals with them thoroughly, we feel no need to raise them here.

17 Community Resistance

The ports of LA/LB are a gateway to Asian imports for the entire country, but the communities close to them bear an unfair share of the costs of this trade, in the form of pollution, congestion, noise, and eyesores. Pollution is created both by steamships and port trucks that operate on diesel fuel. When the ships are docked they keep running their engines. So diesel fumes are continually belched into the air. The port truckers often must stand in line at the terminal gates, waiting to pick up a container. They too keep their engines running, adding to the air pollution.

A study by the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC) and the Coalition for Clean Air rated the environmental record of the ten largest ports in the U.S. The ports of LA/LB received a C- and C on the rating scale. The port complex is described as the single largest fixed source of air pollution in Southern California, emitting as much diesel exhaust as would 16,000 tractor-trailers idling 24 hours a day. The POLA alone produces 31.4 tons a day of nitrous oxide, and 1.8 tons of particulate matter, primarily from ships and trucks (Schoch 3/22/04). A more recent 265-page emissions report, issued by the POLA, found that, together, the ports generate nearly one-quarter of the diesel pollution in the region. It found that oceangoing vessels were the chief source of this pollution (Schoch 7/8/04).

Congestion is especially problematic on the Long Beach Freeway (710), which becomes a sea of port trucks hauling containers, particularly at certain hours of the day. This freeway, which is crumbling and in dire need of repair, is operating at maximum capacity so that a single accident brings it to a halt for hours. The problem is only slightly less on other freeways that are jammed with trucks linked to the ports and to trade. Proposals have been made to widen the 710, but they have failed in the face of community opposition led by the home and business owners adjacent to the freeway whose properties would be wiped out.

The railroads, while frequently seen as solutions to pollution and congestion, can contribute to the latter problem (and are not free from polluting either). When a train crosses a major thoroughfare, traffic can get seriously backed up. The Alameda Corridor project aimed, in part, to eliminate this problem in the route from the ports to downtown Los Angeles. But that trip is only a small part of the lengthy rail trips that are involved in moving freight across and out of Southern California. Once trains leave downtown, they must pass through densely populated areas, crisscrossed with roads, leading to community irritation far beyond the immediate ports area. The same holds true for road and freeway congestion.

Communities close to the ports also complain about unsightly eyesores that clutter their surroundings. These include giant cranes sticking high into the air, stacks of empty containers piled up on every piece of vacant land, and trucks or tractors parked overnight in their neighborhoods. [We personally find the cranes and stacks of containers picturesque and photogenic, but we don’t have to live among them.]

18 All of these complaints extend to the development of warehousing as well. When communities allow warehouses to open, they are encouraging trucks to be driving in and out at all hours of the day and night. Not only are they noisy, but they contribute to congestion and pollution.

These complaints have led to community social movements in some of the cities and communities adjacent to the ports, such as San Pedro and Wilmington, and in some of the cities where warehousing has been or is being developed, including some of the South Bay cities, and Mira Loma in the Inland Empire.

China Shipping Suit.

For this chapter, the most relevant rebellion has been by community residents over the development of a new giant terminal in the POLA for China Shipping. Community and environmental groups decided to sue the City of Los Angeles over the impact of this terminal on the nearby communities of San Pedro and Wilmington. The major complaints concerned increasing diesel fumes from ships and trucks, increased traffic congestion, 16-story-high cranes that block ocean views, and a brownish haze over the coast. Leading the charge was Gail Ruderman Feuer, senior attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). The suit grew out of a growing recognition that the ports of LA/LB generate more air pollution than any other source in the LA basin, but remain largely unregulated. It involved charging the port with not conducting an adequate Environment Impact Report (EIR), which enraged residents about the high- handed decision-making of the port authorities (Schoch 3/6/03).

A settlement favorable to the community groups was reached in March 2003, and the headlong construction of the terminal was brought to a halt. The city had to sign a $60 million agreement with a number of specifications: $10 million for incentives to clean up trucks serving the ports, $20 million for reducing air pollution from port operations, $20 million to mitigate aesthetic impacts on Wilmington and San Pedro, replace four installed cranes with shorter ones, and create a traffic plan for the terminal and other parts of the port. In addition, the port agreed to require non-diesel trucks in the China Shipping terminal yard, and to install electric power for docked ships so they would not have to keep their engines running while in dock. The money would come from port revenues rather than the city (Schoch 3/6/03).

This suit was a warning shot for the trade community, which had been operating on the assumption that everyone in the LA area benefited from the rapid rise in Asian commerce and rapid growth of the ports. It seemed to them like a win-win situation: more economic activity, more good jobs. How could anyone object to the expansion of these highly profitable ports? Yet here they found that some people were so put out that they were ready to go to court to try to stop port expansion. The China Shipping settlement represented recognition that these social costs needed attention and could no longer be ignored.

19 Already some of the terms of this settlement have been introduced. One important innovation, known as cold ironing, involves plugging the ship into the dock so that it relies on electric rather than diesel fuel while it is in the port. The POLA and China Shipping were compelled to install this, and the POLB sought to follow their example. Indeed the LA case has created a new environmental pressure on all ports, nation-wide (Greenberg 4/19/04; Lin 6/22/04; Mongelluzzo 8/11/03).

But the environmentalists were not finished. In mid-2004 a bill was being considered by the State Legislature mandating a cap on emissions at the ports of LA/LB. The bill, proposed by Assemblyman Alan Lowenthal (D-Long Beach), stated that the ports must keep pollution levels at or below existing levels, regardless of trade growth. It would go into effect January 1, 2006, and would require that the ports transform their terminals into so-called “green terminals,” as the POLA’s China Shipping Terminal had been forced to do. If this law passed, it could force limits on port growth. At a minimum, it puts the ports on warning that economic growth cannot be the sole value that is pursued (Greenberg 6/7/04).

Congestion does not only hurt local residents. It also threatens commerce itself, which certainly gets the attention of the authorities. If goods cannot be moved off the docks in a timely fashion, shippers and ocean carriers will start looking for alternative ways to move their containers into the country. This issue became all too clear during the peak season of 2004, when the ports of LA/LB found themselves unable to handle the growth in container traffic. Ships were lined up in the harbor, unable to discharge their containers. This crisis, and its resulting reforms and proposals for reform will be discussed in Chapter 7.

Will the Ports of LA/LB Retain their Dominance?

In October 2002 the West Coast ports faced a lockout of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) by their employers, the Pacific Maritime Association (a consortium of steamship lines and terminal operators) over negotiations for renewing their contract. This lockout, which shut the West Coast ports down for 10 days, at great expense to the U.S. economy, raised consciousness among shippers and carriers alike regarding their dependence on the ports of LA/LB. The country’s reliance on Asian, especially Chinese imports is only expected to increase at a rapid rate. So the question has been put forward: Is there an alternative to reliance on the Southern California ports? We can ask the follow-up question: Is this choke point likely to remain, or will shippers and carriers find alternatives so that they are less vulnerable to a port shut-down?

The lockout did lead to some immediate changes. Wal-Mart, for one, opened a new massive distribution center near the port of Savannah. And we heard a rumor that Target had made plans to import more through the Mexican port of Ensenada. East Coast ports experienced an immediate rise in traffic from Asia as more shippers turned to all-water service through the Panama Canal, and to a lesser extent, the Suez Canal. From the year starting July 2001 and ending June 2002, to the subsequent year, ending June 2003, East

20 Coast ports experienced a 20 percent jump in containerized imports, from 4.5 million to 5.4 million TEUs (Gilligan 8/11/03).

So what are the long term prospects for a shift away from LA/LB as the premier gateway for Asian imports? Such a shift would entail any or all of the following: Increasing the use of the other West Coast ports; expanding all-water services, via either the Panama or the Suez Canal; expansion of East Coast ports so that they can handle the increased capacity; major investment in one or more Mexican ports, including improving the rail and road connections to the U.S. border; and constructing a “dry water” canal across Central America.

For the most part the LA trade community no one seems especially worried that any of these changes are imminent (though see Greenberg 7/7/03 for an alternative perspective). True, some business has been lost to East Coast ports, but the Southern California trade community is still anticipating massive growth in imports from Asia, and still feels that it faces severe challenges in coping with the flood. In other words, local people do not anticipate a fall-off at the local ports. On the contrary, their worries are focused on maintaining and expanding the transportation infrastructure so that they can meet the challenges of ever-increasing container freight. But are they right? Let us consider each of the alternatives: a. Shifting to Other West Coast Ports

In the first five months of 2005, the ports of Seattle, Tacoma and Oakland all experienced an increase in container traffic. According to Mongelluzzo (7/4/05 p.16): “The increase results from decisions by carriers and shippers to seek alternatives to the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach.” This was in direct response to the extreme congestion at the ports of LA/LB during the 2004 peak season because of an unexpected surge in imports of 14 percent at those two ports.

A question can be raised about whether the northern ports can handle an increase in traffic. They claim they can, because they expanded terminals and instituted some operational changes. From May 2004-April 2005, Seattle showed a 45.2 percent increase, and Oakland, a 29.6 percent increase in imports. However, the market share of imports among the top 10 West Coast ports for the three northern ports in that same period was 8.7 percent for Seattle, 7.3 percent for Tacoma, and 6.3 percent for Oakland. This hardly seems to make a dent in the market share of LA/LB among the top 10, which was 76.7 percent for the same period (Mongelluzzo 7/4/05 p.17). So even though diversion has occurred, it is not a serious threat to the dominance of the two Southern California giants. b. Expanding All-Water Services All-water services refer to shipments from Asia to East Coast ports, either by the Panama or the Suez Canals. All-water services are an alternative to intermodal freight transportation through the West Coast ports. Of course, they are irrelevant for the containers that are headed for the Western part of the country. According to Leach

21 (7/4/05 p.12): “Carriers have been eager to add all-water services to feed large retailers’ import-distribution centers on the East Coast and to provide an alternative to congested Southern California ports.”

Let us consider the two canals, followed by a brief examination of the capacity of the East Coast ports to accept added traffic. i. Expanding the Panama Canal. The Panama Canal is restricted to ships of limited size. Panamax ships—the maximum size ship that can fit through its locks and shallowest sections, can only carry up to 2,200 containers, while a number of ships under construction carry over 8,000 TEUs (Emmott 9/1/03; Williams 6/6/04). In bringing in the larger ships, some carriers hope to bump their smaller panamax vessels to the Canal route (Leach 7/4/05).

Apart from its size limitations, the Canal is reaching traffic capacity, at about 13,600 ships per year. On some days, 10 Panamax container vessels from China and other Asian manufacturing countries, are waiting on the Pacific side to get through. The Canal’s regular all-water services (for shipping lines) jumped from 20 in 2001 to 32 in 2003. Each service requires nine vessels to provide a week rotation from Asia, so multiplying 32 by nine entails a substantial number of transits. The Canal can only handle nine Panamax-size vessels per day. Some vessels must discharge some containers to meet the Canal’s draft and line-of-sight restrictions, which causes delays. These are some of the reasons for interest in expansion (Leach 11/24/03).

It is estimated that expanding the canal would require the construction of a new series of larger and deeper locks, costing at least $5 billion. The expansion would require a national referendum, followed by a search for financing. The Canal operates on a for- profit basis, and it would be likely that tolls would have to be raised to pay off the debt. If those tolls were too high, carriers would use other routes, so that the justification for the expansion would be undermined. Feasibility studies are being conducted as a precursor to a possible referendum. The most optimistic projections are that work could begin in 2005 and would not be completed before 2010 (Emmott 9/1/03; Williams 6/6/04).

The InterAmerican Development Bank, and Chile, China, Japan and the U.S. have all expressed interest in helping to finance the expansion. But serious opposition may be raised by the 35,000 landholders and cattle ranchers who would be threatened by reservoirs needed to increase the water in an expanded canal. Demonstrations against Canal expansion have already taken place (Emmott 9/1/03). Even if the Canal is expanded, it is unlikely that the average number of daily ships would go much higher than 50, compared to 35 today (Williams 6/6/04). ii. Expanding the Use of the Suez Canal. One of the major steamship lines, China Shipping, planned to launch a new service from China to the U.S. East Coast via the Suez Canal in September 2005. They planned a westbound round-the-world service from China to Southeast Asia, through the Mediterranean, and on to the U.S. East Coast, and

22 then returning to Asia via Panama. The new service would use 4,200 TEU ships, bigger than can be handled by the Panama Canal. However, a number of carriers were postponing providing such services because of a shortage of ships of the right size (Leach 7/4/05). We can expect this route to be used more, but we doubt it threatens LA/LB in any significant way. iii. Expanding East Coast Port Capacity. All-water service, using the Panama Canal and discharging Asian-originating containers at East Coast ports, takes a week longer than discharging from the ships on the West Coast, and shipping intermodally back East. The latter form of freight movement is more expensive, but for many companies, the time advantage is critical. Both fear of the power of the ILWU on the West Coast, a power not equaled by the East Coast union, the International Longshore Association (ILA), and the rise in congestion in LA/LB, threaten this advantage. Congestion, as we shall see in Chapter 7, can be caused by any number of breakdowns, including failure of the railroads to keep the cargo moving, and wildcat strikes by port truckers. As a representative of Reebok puts it: “The reliability is greater if the cargo stays on the ocean carrier’s assets. They run like clockwork. The other parts of the network have problems” (cited in Gilligan 8/11/03 p.22).

There has been a definite growth in Asia trade through East Coast ports. In 2002 the East Coast’s share of Asian cargo increased from 18.6 to 21 percent of the total, but the rise has not always been smooth. East Coast ports have their own capacity and congestion problems. Almost all the East Coast ports are engaging in expansion programs, and they are starting to compete with one another for intermodal traffic from Asia. NY/NJ showed a 10.09 percent growth in TEUs from 2003 to 2004, and Charleston, SC grew by 10.24 percent (Leach 8/1/05).

Still, it seems unlikely that the ports of LA/LB should feel threatened by this alternative. According to a maritime consulting firm representative:

The East Coast will slowly and steadily build their shares of Asian cargo. They’re not going to put the West Coast ports out of business, because the market is growing so steadily. If the East Coast picks up 1 or 2 percent of total market share of China trade every year, that’s a lot of cargo. Every year, you’ll need a new Baltimore [referring to port facilities the size of the Port of Baltimore] (cited in Gilligan 8/11/03 p.24).

Another factor which may limit a preference for East Coast ports concerns an improvement in intermodal freight transportation: the alleviation of rail congestion in Chicago. Most containers discharged on the West Coast and shipped East by intermodal rail must pass through Chicago, which handled 42 percent of all of the nation’s intermodal traffic (not just coming from the West Coast) in 2002. Chicago has proved to be a chokepoint, delaying the movement from the West Coast ports to the Atlantic seaboard by one or two days. Both the Union Pacific and the Burlington Northern Santa Fe railroads have opened new intermodal yards outside of Chicago to avoid the

23 congestion of downtown. The shift to these new yards should help the West Coast ports regain some of the market share they have lost (Mongelluzzo 9/15/04). c. Shifting to Latin America

Another approach is to shift imports to ports south of the border. One approach is to develop Mexican ports. Another is to try to develop a “dry water canal” across a narrow land-mass in Central America. i. Expanding Mexican Ports. During the lockout on the West Coast in October 2002, some carriers diverted ships to Mexican ports on the Pacific Coast. But the amount of cargo involved was limited, and most steamship line executives do not anticipate that Mexico would become a major competitor in the trans-Pacific container trade any time soon. However, some moves have been made in that direction (Dupin 10/14/02).

Stevedoring Services of America (SSA) has a 49 percent stake in a terminal at the port of Manzanillo, and Hutchison Ports Mexico, owned by Hutchison Port Holdings, the largest port operator in the world, operates the Port of Ensenada. So far these ports serve mainly Mexican markets, but terminal facilities and rail connections could be expanded to provide an alternative for U.S. imports (Dupin 10/14/02). However, “Many shipping executives doubt it will ever happen. Except in isolated cases, most shippers have shown little inclination to accept a more indirect routing and to expose their cargoes to a Mexican transit that is considered less secure and less reliable than shipment to U.S. West Coast ports” (Dupin 2002 p.16).

Apart from this reluctance, Mexican ports are far from prepared to receive high volumes of containerized cargo. In 2001, Ensenada (which is in Baja California, near San Diego) only received 30,000 TEUs in total, and can only handle ships of 3,000 TEUs or less in size. Expansion plans would allow the port to handle 500,000 TEUs per year, hardly serious competition for LA/LB’s millions. Moreover the port lacks rail connections (Dupin 10/14/02).

Manzanillo, which is much further south, has a better chance of developing intermodal service into the U.S. It handled 547,946 TEUs in 2001, and could expand its capacity to 1 million TEUs. The port is closer to Dallas than is Southern California, and could be used to distribute cargo from Asia to the Midwest and Southeast. It presently has rail connections to Texas but they are not up to U.S. standards. Mexican railroads have recently been privatized, and more investment is going into them, but they still have a long way to go. In addition, to make this plan a reality, not only would rail service have to improve, but an agreement would have to be signed between the U.S. and Mexico allowing cargo to cross the border in-bond. Moreover, shippers and carriers would have to be convinced that they would not have to face corruption, delays, and cargo theft, all notorious problems in Mexico (Dupin 10/14/02; Barnett 10/14/02).

Regarding Manzanillo, the Cunningham Report (11/18/02) stated:

24 Better logistics overall would be required to make the trade route [into the U.S.] viable. For now, the West Coast ports remain the best bet for getting cargo from across the Pacific. But the recent lockout at West Coast ports reminded shippers that it’s always good to have a backup plan. And while supporters of the alternate route through Mexico don’t imagine their success would decrease business at the West Coast ports, they figure the trade is growing quickly enough for there to be plenty of business for everyone (emphasis added).

Another idea along these lines was to try to create an entity called NAFTA Rail, which would link three railroads and create a rail corridor from Mexico through to Canada. This is also aimed at by-passing US West Coast ports, but at the time of writing, it was caught up in legal wrangling (Cunningham Report 9/8/03). ii. Constructing a “Dry Water” Canal Across Central America. The idea here is to develop a rail or highway system across Central America, connecting the Pacific to the Caribbean that would compete with the Panama Canal. Panama has already constructed a rail link, which opened in November, 2001. El Salvador and Honduras have discussed a 135 mile highway between ports. Nicaragua also contemplated a highway project between two of its ports. Both of these projects would require considerable expenditures for port and road infrastructure (Luxner 3/25/02).

The latest idea is that Nicaragua would construct a high-speed railroad across the country. Vessels would discharge on the West Coast, and other vessels would be loaded in the Caribbean for ocean shipment up to US East Coast docks. This would speed up moves in comparison to the Panama Canal (Emmott 9/1/03).

So far the already existing 47.6 mile Panama Canal Railway has not developed into a significant alternative to landbridge in the United States. The railroad is operated by a joint venture of Kansas City Southern RR and Mi-Jack Products, and has mainly involved the repositioning of empty containers to avoid high-priced Canal tolls (Luxner 3/25/02; Leach 11/24/03).

Conclusions

In this Chapter we have examined the rise of the Ports of LA/LB as the premier gateway to growing Asian (especially Chinese) exports to the United States. We considered the reasons for the LA/LB’s pre-eminence, including the rise of intermodalism as a major method for bringing Asian cargo to mid-western and eastern markets, and the natural and self-constructed advantages of Southern California as an international trade center. But this growth is not going unchallenged, by local residents who bear an unfair share of the burdens associated with a growth in the nation’s trade, by shippers who are afraid of too much dependence on one location, and by competitors eager to increase their share of the Asian traffic. Still, we conclude that, at least in the short term, the ports of LA/LB are likely to continue to reign and, unless they strangle in the congestion they are creating, or the U.S. trade and government deficits create an international crisis, it is hard to imagine that their growth will not continue at an almost frightening pace.

25 References

Barnett, Chris. 10/14/02. “Navigating Mexico’s logistics.” Journal of Commerce p.18.

______. 10/14/02. “The hot zone for hijackings: Cargo theft remains a problem in Mexico.” Journal of Commerce pp.19-21.

Bonney, Joseph. 7/19/04. “Growth market: Annual list of top 50 container ports reveals broad increase in volume.” Journal of Commerce, pp.16-17.

Boschken, Herman L. 1988. Strategic Design and Organizational Change: Pacific Rim Seaports in Transition. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

Calix, Robert, Project Manager. 2002. Southern California Freight Management Case Study (Six County SCAG Region). Los Angeles: LA County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), Southern California Association of Governments (SCAG), California Department of Transportation (DOT).

Campbell, Scott. 1993. “Increasing trade, declining port cities: Port containerization and the regional diffusion of economic benefits.” Pp. 212-255 in Trading Industries, Trading Regions: International Trade, American Industry, and Regional Economic Development, edited by Helzi Noponen, Julie Graham and Ann R. Markusen. New York: Guilford.

Chadwin, Mark L., James A. Pope, and Wayne K. Talley. 1990. Ocean Container Transportation: A Operational Perspective. New York: Taylor and Francis.

Chilcote, Paul W. 1988. “The containerization story: Meeting the competition in trade.” Pp. 125-145 in Urban Ports and Harbor Management: Responding to Change Along U.S. Waterfronts, edited by Marc J. Hershman. New York: Taylor and Francis.

Corbett, Kevin S. 1996. “Double or nothing: The big stakes of hub ports.” Journal of Urban Technology 3:1-10.

Cunningham Report. 11/18/02. “Kansas City Southern seeking Mexican port connection.” Cunningham Report

______. 9/8/03. “Mexico-to-Canada rail plan headed for court.” Cunningham Report.

DeBoer, David J. and Lawrence H. Kaufman. 2002. An American Transportation Story: The Obstacles, the Challenge, the Promise. Greenbelt, MD: Intermodal Association of North America (IANA).

26 Dowd, Thomas J. 1988. “Port finances and operations: Understanding the bottom line.” Pp. 217-233 in Urban Ports and Harbor Management, edited by Marc J. Hershman. New York: Taylor and Francis.

Dupin, Chris. 10/14/02. “Mexican port alternative? Not yet.” Journal of Commerce pp.16-17.

Emmott, Robin. 9/1/03. “A question of economics: Panama is edging closer to a decision of whether to expand the canal.” Journal of Commerce pp.48-51.

Erie, Steven P. 2004. Globalizing L.A.: Trade, Infrastructure, and Regional Development. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Gilligan, Eugene. 8/11/03. “Off to the races: Special report on East Coast ports.” Journal of Commerce pp.22-28.

Greenberg, David. 2/10/03. “Shutdown doesn’t stop record year moving cargo at ports.” Los Angeles Business Journal p.6.

______. 7/7/03. “Direct route to the East by importers worries area ports.” LABJ p.1.

______. 4/19/04. “Long Beach Commissioners seek ‘cold-ironing’ proposal.” LABJ p.13.

______. 6/7/04. “Proposed cap on pollution at ports could crimp growth.” LABJ p.10.

______. 7/19/04. “Long Beach port catching up to L.A. in cargo traffic.” LABJ p.10.

Gulick, John. 1998. “‘It’s all about market share”: Competition among U.S. west coast ports for trans-Pacific containerized cargo.” Pp. 61-83 in Space and Transport in the World-System, edited by Paul S. Ciccantell and Stephen G. Bunker. Westport, CT: Greenwood.

______. 2001. Landside Risks: The Ecological Contradictions of Port of Oakland Globalism. Sociology Ph.D. dissertation, UC Santa Cruz.

Hall, Peter Voss. 2002. The Institution of Infrastructure and the Development of Port- Regions. Ph.D. dissertation in City and Regional Planning, UC Berkeley.

Ibold, Hans. 6/18/01. “L.A. ranks as 16th largest economy in the world.” Los Angeles Business Journal, p.8.

Journal of Commerce (JoC). 4/9/02. “Top 100 importers and exporters,” pp.1A-56A.

27 JoC. 3/4/02. “Trans-Pacific ocean trade.”

JoC. 3/3/03. “Trans-Pacific container logistics,” pp.18-42.

JoC. 7/14/03. “World’s top 50 container ports,” pp.26-34.

JoC. 7/19/04. “World’s top 50 container ports, pp.18-26.

Kyser, Jack. 2004. International Trade Trends and Impacts: The Southern California Region: 2003 Results and 2004 Outlook. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation (LAEDC).

Leach, Peter T. 11/24/03. “Growing pains: Reopened two years ago, the Panama Canal Railway is off to a slow start.” Journal of Commerce pp.18-20.

______. 7/4/05. “Here they come: All-water services from Asia to the East Coast will increase during the next year.” Journal of Commers pp.12-14.

______. 8/1/05. “Head to head: East Coast ports intensify competition for intermodal cargo.” Journal of Commerce pp.12-14.

Lin, Sara. 6/22/04. “Cargo ship plugs into new technology at Port of L.A.” Los Angeles Times B1.