Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release

Contact: Communications Department 212-857-0045 [email protected] media release Martin Munkacsi: Think While You Shoot! On view from January 19 through April 29, 2007 Media Preview January 18, 2007 9:30 - 11am RSVP: [email protected] 212.857.0045 Martin Munkacsi Fred Astaire on his Toes, 1936 Courtesy the Collection of F.C. Gundlach As she runs toward him on a chilly Long Island beach in November of 1933, Martin Munkacsi snaps a photo of a model dressed in a fashionable swimsuit. In that instant he revolutionizes fashion photography forever. Freeing photographers from the confines of their studios and models from their rigid poses, Munkacsi (1896-1963) introduced fresh ideas and a new spontaneity to the world of fashion imagery. Martin Munkacsi: Think While You Shoot!, which is on exhibition at the International Center of Photography (1133 Avenue of the Americas at 43rd Street) from January 19 through April 29, 2007, will offer a rare opportunity to view this and other works by the remarkable yet under-appreciated photographer. The entire range of Munkacsi’s work, including the photojournalism from the 1920s and 1930s done in Hungary and Germany, his far-ranging international photo reportage, his sports photography, and fashion photography will be seen in this retrospective exhibition, which was originated by Prof. F.C. Gundlach at the Haus der Photographie in Hamburg. The ICP presentation of the exhibition Martin Munkacsi: Think While You Shoot!, organized by ICP curator Carol Squiers in conjunction with Sandra S. Phillips, Senior Curator of Photography at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, will present over 140 works, including vintage prints drawn from public and private collections along with vintage fashion and news magazines. -

For Immediate Release

Martin Munkacsi VITALITY 20 March – 16 May, 2009 Opening Reception Thursday, 19 March, 6-8pm Lucille Brokaw, Piping Rock Beach, L.I. 1933 Gelatin silver print; printed c.1933 Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York is pleased to announce an exhibition of rare vintage prints by one of the twentieth century’s preeminent masters of photography. The exhibition coincides with Munkacsi’s Lost Archive at New York’s International Center of Photography. In Europe until 1934 and in America thereafter, Hungarian born photographer Martin Munkacsi (1896-1963) single-handedly changed the look of photojournalism and fashion photography. Munkacsi defied convention by incorporating a sense of motion, dramatic camera angles, and elements of whimsy into his work. His vision is now well understood to have had an impact on an entire generation of photographers. This exhibition explores this influence through many of Munkasci’s iconic images including Lucile Brokaw, Piping Rock Beach, Long Island, 1933 (above). Born in Kolozsvar, Hungary, Munkacsi arrived in Budapest in 1912 and started out writing for newspapers. Later he taught himself photography as a way to sell his stories. In 1921 he began to photograph sports for the magazine Az Est, demonstrating a talent for timing and drama. In 1928 he left Budapest for Berlin and became chief photographer for Germany’s Ullstein Press working for Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung and other prominent photo weeklies. In the years prior to the war, Munkacsi traveled extensively, including trips to Algeria, Egypt, Liberia, Palestine, Turkey, and various European destinations. Munkacsi even once traveled in a zeppelin to North America. It is significant that both Henri Cartier-Bresson and Richard Avedon credit Munkacsi with being instrumental in the development of their styles. -

The History of Photography: the Research Library of the Mack Lee

THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Research Library of the Mack Lee Gallery 2,633 titles in circa 3,140 volumes Lee Gallery Photography Research Library Comprising over 3,100 volumes of monographs, exhibition catalogues and periodicals, the Lee Gallery Photography Research Library provides an overview of the history of photography, with a focus on the nineteenth century, in particular on the first three decades after the invention photography. Strengths of the Lee Library include American, British, and French photography and photographers. The publications on French 19th- century material (numbering well over 100), include many uncommon specialized catalogues from French regional museums and galleries, on the major photographers of the time, such as Eugène Atget, Daguerre, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Marville, Félix Nadar, Charles Nègre, and others. In addition, it is noteworthy that the library includes many small exhibition catalogues, which are often the only publication on specific photographers’ work, providing invaluable research material. The major developments and evolutions in the history of photography are covered, including numerous titles on the pioneers of photography and photographic processes such as daguerreotypes, calotypes, and the invention of negative-positive photography. The Lee Gallery Library has great depth in the Pictorialist Photography aesthetic movement, the Photo- Secession and the circle of Alfred Stieglitz, as evidenced by the numerous titles on American photography of the early 20th-century. This is supplemented by concentrations of books on the photography of the American Civil War and the exploration of the American West. Photojournalism is also well represented, from war documentary to Farm Security Administration and LIFE photography. -

Update for UPDIG the Universal Photographic Digital Imaging Guidelines

outTAKES NEWS leadership on issues affecting the PLUS License Generator, LibreDigital? If HarperCollins is stock photographers. As 2006 SAA License Information Panels, License eventually getting profit from there, Update for UPDIG president David Sanger said, “The Embedder & Decoder, Artist & will they cut sweetheart deals to The Universal Photographic Digital principles of SAA include fair busi- Licensor Registry and the License pay a premium for the service Imaging Guidelines (UPDIG) have ness practices, an equitable split of Registry, all launching in 2007. because they know the money still been updated and revised and revenue, shared risk and respon- To learn more about joining the goes back into their pockets even can be found at UPDIG.org. A sibility, mutual trust and respect, PLUS Coalition and using the PLUS though that amount won’t be part free, downloadable PDF version is and recognition of the rights of the standards, visit the PLUS website at of royalty calculations? And exactly available. creator. These have not changed useplus.org. how much do you make off elec- and they transcend any specific tronic distribution? The publishing The 12 guidelines are organized licensing model. We believe that the Anonymous is Jahangir Razmi world is changing, and now is the into a Quick Guide (executive same principles should apply to all An Iranian photographer, whose time to carefully negotiate what summary) and a Complete Guide. stock photography contracts.” The image of an execution won a 1980 you’ll allow companies to do with The aim is to clarify the issues SAA website address is stockartist- Pulitzer Prize, has been recog- your intellectual property.— From affecting accurate reproduction and salliance.org. -

Cover of the Manuscript For

©2010 COPYRIGHT FOR THIS WORK IS HELD BY DAVID J. MARCOU AND MATTHEW A. MARCOU CoverAll Picture of the Manuscript Post photos, for 1937: -1957, are derived from the Hulton Collection and are provided courtesy of Getty Images. Other illustrations for this text can be found at the end of this book in the appendix. CREDIT MUST BE GIVEN TO DAVID J. MARCOU AS AUTHOR All the Best Britain’s Picture Post Magazine, Best Mirror and Old Friend to Many, 1938-57. First cover of Picture Post Magazine, Oct. 1, 1938 taken by Kurt Hutton; Photo courtesy of Getty Images #74218345 Researched and Written by David J. Marcou. Original Draft‘s Copyright©1993 David J. Marcou and Matthew A. Marcou. Final Draft‘s Copyright©2010++ David J. Marcou and Matthew A. Marcou. For my parents (David Ambrose and Rose Caroline Marcou), my son (Matthew Ambrose Marcou), the rest of our family, our friends, all my editors, publishers, students, teachers, as well as the diverse and talented people (living or deceased) who made a profound contribution to the art of the photo-essay with Picture Post -- especially Stefan Lorant, Sir Edward Hulton, Sir Tom Hopkinson, Bert and Sheila Hardy, James Cameron, Nachum Tim Gidal, Robert Kee, Matthew Butson (of Getty Images), and Jon Tarrant, former editor of the British Journal of Photography, the staffs of the La Crosse Public Library (the online publisher for this text, with the UW-La Crosse Library), Wisconsin Historical Society, National Portrait Gallery of Britain, the Smithsonian Institution, the Museum of Modern Art, the International Center of Photography, the George Eastman House Library, the British Museum, the national libraries of South Korea, Britain, France, Ireland, the Philippines, Australia, and America, and all those who assist the lives of myself and my extended family. -

American Cool Exhibition List

American Cool MUHAMMAD ALI Artist: Thomas Hoepker 1966 (printed 2013) Modern print Image: 38.1 × 56.8cm (15 × 22 3/8") Sheet: 50.8 x 61cm (20 x 24") Magnum Photos EXH.CL.86 FRED ASTAIRE Artist: Martin Munkacsi 1936 Gelatin silver print Image (Image, Accurate): 24.1 x 19cm (9 1/2 x 7 1/2") Sheet (Sheet, Accurate): 25.2 x 20.1cm (9 15/16 x 7 15/16") National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution NPG.93.98 LAUREN BACALL Artist: Alfred Eisenstaedt 1949 (printed 2013) Pigmented ink jet print Sheet: 48.3 × 33cm (19 × 13") Image: 40.3 × 27.9cm (15 7/8 × 11") EXH.EE.1648 JAMES BALDWIN Artist: Carl Van Vechten 1955 Gelatin silver print Image: 24.9 x 17.6 cm (9 13/16 x 6 15/16") Mat: 55.9 x 40.6 cm (22 x 16") National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution NPG.91.66 AFRIKA BAMBAATAA Artist: Laura Levine 1983 Gelatin silver print Image: 20.4 x 13.5 cm (8 1/16 x 5 5/16") Sheet: 25.3 x 20.2 cm (9 15/16 x 7 15/16") National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution NPG.2012.4 2/5/2014 ~ Images are for study purposes only and may not be reproduced without permission of the owner ~ Page 1 of 22 JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT Artist: Dmitri Kasterine 1986 Gelatin silver print Image: 38.3 x 37.7cm (15 1/16 x 14 13/16") Sheet: 50.5 x 40.6cm (19 7/8 x 16") National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution NPG.2011.24 BIX BEIDERBECKE Artist: Unidentified Artist c. -

Read a Free Sample

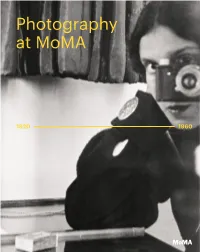

Photography at MoMA Contributors Quentin Bajac is The Joel and Anne Ehrenkranz Chief Curator of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Museum of Modern Art draws upon the exceptional depth of its collection to tell a new history of photography in the three-volume series Photography at MoMA. Douglas Coupland is a Vancouver-based artist, writer, and cultural critic. The works in Photography at MoMA: 1920–1960 chart the explosive development Lucy Gallun is Assistant Curator in the Department of the medium during the height of the modernist period, as photography evolved of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art, from a tool of documentation and identification into one of tremendous variety. New York. The result was nothing less than a transformed rapport with the visible world: Roxana Marcoci is Senior Curator in the Department Walker Evans's documentary style and Dora Maar's Surrealist exercises in chance; of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art, El Lissitzky's photomontages and August Sander's unflinching objectivity; New York. the iconic news images published in the New York Times and Man Ray's darkroom experiments; Tina Modotti's socioartistic approach and anonymous snapshots Sarah Hermanson Meister is Curator in the Department of Photography at The Museum taken by amateur photographers all over the world. In eight chapters arranged of Modern Art, New York. by theme, this book presents more than two hundred artists, including Berenice Abbott, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Geraldo de Barros, Margaret Bourke-White, Kevin Moore is an independent curator, writer, Bill Brandt, Claude Cahun, Harry Callahan, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Roy DeCarava, and advisor in New York. -

Media Release

Contact: Communications Department 212.857.0045 [email protected] media release Munkacsi’s Lost Archive On view from January 16, 2009 through May 3, 2009 Media Preview January 15, 2009 9:30–11:00 am RSVP: [email protected] 212.857.0045 Martin Munkacsi [Tibor von Halmay and Vera Mahlke], ca. 1931 © Joan Munkacsi, courtesy International Center of Photography Hungarian photographer Martin Munkacsi (1896–1963) created dynamic and elegant images of models and athletes in motion. His unique style—inspiring photographers from Henri Cartier-Bresson to Richard Avedon—grew out of the context of 1930s photojournalism and required a combination of split-second timing and radical cropping. For Munkacsi, process was key. The recent rediscovery of his long-lost negative archive helps to clarify his working methods and uncover the secrets behind his most famous images. Drawn from the collection of over 4,000 glass negatives recently acquired by the International Center of Photography, this exhibition will include vintage and modern prints, as well as some original negatives, many still in their boxes with Munkacsi’s handwritten annotations. The exhibition will be on view at ICP (1133 Avenue of the Americas at 43rd Street) from January 16 to May 3, 2009. Martin Munkacsi began his career as a writer, publishing interviews and poems as well as sports coverage in several Budapest newspapers. In 1925, he started publishing his vibrant photographs of sporting events, while also operating a portrait studio. Moving to Berlin in 1928, he signed a contract with the publishing house Ullstein, and quickly became a regular contributor to Die Dame, Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung, and other prominent photo weeklies, shooting sports, travel, and lifestyle pictures. -

Licences Now Available Bestseller Licences

LicencesLicences 2015 Now available Bestseller Licences LICENCES Before They Pass Away – Jimmy Nelson 4 The Family Album of Wild Africa – Laurent Baheux 6 Arctica: The Vanishing North – Sebastian Copeland 7 Africa – Michael Poliza 8 Pictures – Tim Walker 9 Elliott Erwitt’s New York 10 Elliott Erwitt’s Paris 11 Personal Best – Elliott Erwitt 12 Regarding Women – Elliott Erwitt 13 Angels – Russell James 14 Russell James 15 Brazil – Olaf Heine 16 North Korea – Julia Leeb 17 The Stylish Life – Equestrian 18 The Stylish Life – Yachting 19 The Stylish Life – Tennis 20 The Stylish Life – Football 21 The Stylish Life – Golf 22 The Stylish Life – Skiing 23 Living in Style – City 24 Living in Style – Country 25 Living in Style – London 26 Living in Style – Morocco 27 Living in Style – Mountain Chalets 28 Living in Style – New York 29 Living in Style – Scandinavia 30 How We Live – Marcia Prentice 31 A Passion for Cars 32 The Classic Cars Book – René Staud 33 Mercedes Benz – The Grand Cabrios & Coupés – René Staud 34 The Porsche 911 Book – René Staud 35 BMW Motorrad – Make Life a Ride 36 Luxury Toys for Men – The Ultimate Collection 37 The Grand Châteaux of Bordeaux 38 Spirit of Place – Aurélien Villette 39 A Cat’s Life – Gemma Corell 40 The Wedding Book – Everything You Need to Know 41 For the Love of Bags 42 For the Love of Shoes – Patrice Farameh 43 Everyone Loves New York – Leslie Jonath 44 The Watch Book – Gisbert L. Brunner & Christian Pfeiffer-Belli 45 FC Bayern Helden – Detlef Vetten 46 Before They Pass Away Jimmy Nelson This historic volume showcases tribal cultures around the world. -

Martin Munkacsi

MARTIN MUNKACSI think while you shoot Munkácsi Márton (1896–1963), Márton Munkácsi (1896-1963) vagy, ahogy világszerte ismerik: or as he is known worldwide, MARTIN MUNKACSI Martin Munkacsi, a fotómûvészet Martin Munkacsi, is one of the think while you shoot egyik legfontosabb huszadik szá- most important innovators of 20th 2010.10.07. 2011.01.09. zadi megújítója. century photography. kurátor | curated by F.C. Gundlach Miként a szintén magyar születésû Like other Hungarian-born André Kertész, Brassaï, Moholy-Nagy photographers, such as André Kertész, koordinátorok | coordinators Oltai Kata, Sebastian Lux László vagy Robert Capa, ô is külföldön Brassaï, László Moholy-Nagy or Robert lett világhírû, de Magyarországon talán az Capa, Márton Munkácsi also became asszisztens | assistant ô életmûve a legkevésbé ismert a széle- world famous abroad, but unlike his well- Stánitz Zsuzsanna sebb nagyközönség elôtt. known fellow countrymen, his oeuvre is Mûveinek a Magyar Fotográfiai Múze- the least known in Hungary. umban ôrzött részét kisebb tárlatokon, A collection of his works kept in the vagy nagyobb csoportos kiállításokon Hungarian Museum of Photography has láthattuk már, de az életmû, a maga tel- already been exhibited in smaller shows jességében, most elôször a Ludwig Múze- and group exhibitions, but this is the first szerkesztô | editor umban kerül bemutatásra. time that the entire life-achievement is Oltai Kata Pedig jelentôsége valóban Robert exhibited in the Ludwig Museum. szöveggondozás | proofreading Capáéhoz mérhetô: ahogy Capa a hadi- The significance of Munkácsi’s Kürti Emese, Kozma Zsolt Külön köszönet a kölcsönzôknek tudósításaival, Munkácsi riport-, sport- és contribution can only be compared to Special thanks to the lenders fordítás | translation divatfotóival járult hozzá a modern fotó- that of Robert Capa.