Copyright by Gordon Moakes 2019 the Report Committee for Gordon Moakes Certifies That This Is the Approved Version of the Following Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

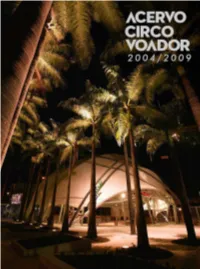

Acervo-Circovoador 2004-2009.Pdf

2004/2009 Primeira Edição Rio de Janeiro 2017 Roberta Sá 19/01/2009 Foto Lucíola Villela EXTRA / Agência O Globo Sumário 6 Circo Voador 8.Apresentação 21.Linha do Tempo/ Coleção de MiniDV 2004/2009 7 Apresentação Depois de mais de sete anos fechado, o Circo 13/07/2004 Voador foi reinaugurado no dia 22 de julho de Foto Michel Filho 2004. Os anos entre o fechamento e a reabertura Agência O Globo foram de muita militância cultural, política e judicial, num movimento que reuniu pessoas da classe artística e políticos comprometidos com as causas culturais. Vencedor de uma ação popular, o Circo Voador ganhou o direito de voltar ao funcionamento, e a prefeitura do Rio de Janeiro ‒ que havia demolido o arcabouço anterior ‒ foi obrigada a construir uma nova estrutura para a casa. Com uma nova arquitetura, futurista e mais atenta às questões acústicas inerentes a uma casa de shows, o Circo retomou as atividades no segundo semestre de 2004 e segue ininterruptamente oferecendo opções de diversão, alegria e formação artística ao público do Rio e a todos os amantes de música e arte em geral. 8 Circo Voador Apresentação Uma característica do Acervo Circo Voador pós-reabertura é que a grande maioria dos eventos tem registro filmado. Ao contrário do período 1982-1996, que conta com uma cobertura significativa mas relativamente pequena (menos de 15% dos shows filmados), após 2004 temos mais de 95% dos eventos registrados em vídeo. O formato do período que este catálogo abrange, que vai de 2004 a 2009, é a fita MiniDV, extremamente popular à época por sua relação custo-benefício e pela resolução de imagem sensivelmente melhor do que outros formatos profissionais e semiprofissionais. -

Property Developers Leave Students in the Lurch

Issue1005.02.16 thegryphon.co.uk News p.5 TheGryphon speaks to University SecretaryRoger Gairabout PREVENTand tuitionfees Features p.10 Hannah Macaulayexplores the possible growth of veganism in 2016 [Image: 20th Century Fox] S [Image: AndyWhitton] Sport TheGryphon explores theincreasing In TheMiddle catchupwith p.19 Allthe lastestnewsand resultsfrom •similaritiesbetween sciencefiction •MysteryJetsbefore theirrecentgig thereturnofBUCSfixtures and reality p.17 at HeadrowHouse ITMp.4 [Image: Jack Roberts] Property Developers Leave Students In TheLurch accommodation until December 2015, parents were refusing to paythe fees for Jessica Murray and were informed that the halls would the first term of residence, or were only News Editor have abuilding certificate at this point. paying apercentage of the full rent owed. Property development companyPinna- According to the parent, whowishes to Agroup of Leeds University students cle Alliance have faced critcism for fail- remain anonymous, the ground floor of have also contacted TheGryphon after ing to complete building work on time, the accommodation wasstill completely they were forced in to finding new accom- leaving manystudents without accommo- unfinished and open to the elements, with modation in September due to their flat on dation or living in half finished develop- security guards patrolling the develop- 75 Hyde Park Road still being under de- ments. ment at all times to prevent break ins. velopment by Pinnacle. Pinnacle began development of Asquith Theparent also stated that the building Thethree students, whodonot wish to House and Austin Hall, twopurpose built had afire safety certificate for habitation be named, signed for the three-bedroom private halls of residence situated next to on the floors above the ground floor,but flat in March 2015, and they state that at Leodis, in January 2015, and students who afull building certificate had not been the end of July they were informed that the signed contracts were to move in Septem- signed off. -

Farewell John Deen

W E D N E S D A Y February 21, 2007 Volume 16, Issue 4 www.stonewallnews.net News Northwest Serving the GLBTQA Community of the Pacific Northwest since 1992 Farewell John Deen Stonewall News Northwest turns 15! Now published every other week! Next Issue: Wednesday, March 7th Ad and Content Deadline: Wednesday, February 28th Photo by Mike Schultz Mike by Photo Dean Lynch speaks to a packed house at the John Deen Memorial Celebration at Dempsey’s Brass Rail in Spokane on Sunday, Feb 11th, 2007. Others gathered also shared stories and memories of Deen, former decade long Stonewall News Northwest publisher, and his impact on their lives. Tributes to Deen can also be found in other publications: Editorial A Generous Life, The Spokesman-Re- view, Page B4, February 14, 2007; Publisher Deen fought for rights, The Spokesman-Review, Front Page, February 12, 2007; Remem- bering John Deen, The Pacific Northwest Inlander, Page 14, February 8, 2007. Links to these articles can also be found on Stonewall’s website, www.stonewallnews.net/johndeen.htm. EWU’s SAFE works toward Issues available free throughout the open and accepting campus Pacific Northwest and at By Joyce Crosby www.stonewallnews.net Special to Stonewall News Northwest been close friends ever since,” Gudith said happily. “I slowly started to come out SPOKANE, Wash - When Adam to a few select people, first a friend who Gudith, 21, moved into the dorms on worked in a theater, and then a teacher THIS ISSUE Eastern Washington University in the in the women’s studies department. -

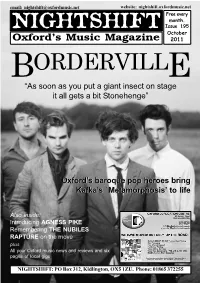

Issue 195.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 195 October Oxford’s Music Magazine 2011 BORDERVILLE “As soon as you put a giant insect on stage it all gets a bit Stonehenge” Oxford’sOxford’s baroquebaroque poppop heroesheroes bringbring Kafka’sKafka’s `Metamorphosis’`Metamorphosis’ toto lifelife Also inside: Introducing AGNESS PIKE Remembering THE NUBILES RAPTURE on the move plus All your Oxford music news and reviews and six pages of local gigs NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Truck Store is set to bow out with a weekend of live music on the 1st and 2nd October. Check with the shop for details. THE SUMMER FAYRE FREE FESTIVAL due to be held in South Park at the beginning of September was cancelled two days beforehand TRUCK STORE on Cowley Road after the organisers were faced with is set to close this month and will a severe weather warning for the be relocating to Gloucester Green weekend. Although the bad weather as a Rapture store. The shop, didn’t materialise, Gecko Events, which opened back in February as based in Milton Keynes, took the a partnership between Rapture in decision to cancel the festival rather Witney and the Truck organisation, than face potentially crippling will open in the corner unit at losses. With the festival a free Gloucester Green previously event the promoters were relying on bar and food revenue to cover occupied by Massive Records and KARMA TO BURN will headline this year’s Audioscope mini-festival. -

BANDS APART FESTIVAL 2009 Completato Il Cast Della III EDIZIONE > > > BANDS APART FESTIVAL 2009

BANDS APART FESTIVAL 2009 Completato il cast della III EDIZIONE > > > BANDS APART FESTIVAL 2009 Completato il cast della terza edizione del Bands Apart Festival, appuntamento diventato ormai consueto dove si esibiscono le migliori band del rock alternativo nel magnifico e suggestivo scenario di Piazza Castello a Ferrara. Ai già annunciati Bloc Party, che per la prima volta presenteranno il nuovo album Intimacy in Italia, ai White Lies, band rivelazione del rock inglese, il cui album d’esordio ha debuttato al primo posto della classifica UK, e ai Tv On The Radio che tornano nel nostro paese dopo che l’ultimo album Dear Science ha dominato le classifiche dei migliori dischi del 2008 delle maggiori riviste musicali mondiali, si aggiungono i celebrati Animal Collective il cui nuovo album Merriweather Post Pavillion già considerato uno dei dischi del 2009 La prima edizione del Bands Apart Festival nel 2007 ha presentato gli Arcade Fire e gli Arctic Monkeys assieme ai The Coral con oltre 9.000 spettatori nell’arco delle due serate, mentre i protagonisti di quella del 2008 sono stati i Franz Ferdinand, gli Interpol e i dEUS con oltre 10.000 spettatori. Intimacy è il terzo album dei Bloc Party. Il disco è stato pubblicato digitalmente appena 4 giorni dopo essere stato ultimato, un record. Prodotto da Paul Epworth e Jacknife Lee il disco oscilla tra il suono classico della band e episodi molto più sperimentali per un disco radicale, pieno di innovazioni ritmiche, riff incendiari, campionamenti orchestrali, un candore feroce e canzoni sfrontate Anche tematicamente c’è un cambiamento, dalle polemiche osservazioni della vita londinese del disco precedente si passa alle emozioni, ai rapporti, amore e brutte separazioni. -

No Risk Disc: LIANNE LA HAVAS

Het blad van/voor muziekliefhebbers 10 augustus 2012 nr. 289 No Risk Disc: LIANNE LA HAVAS www.platomania.nl • www.sounds-venlo.nl • www.kroese-online.nl • www.velvetmusic.nl • www.waterput.nl • www.de-drvkkery.nl PomANIAP & Rock 288 N RISK DISCNIET GOED GELD TERUG LIANNE LA HAVAS Is Your Love Big Enough? (Warner) Hartverwarmende soulminiatuurtjes zijn de specialiteit van deze innemende 22-jarige zangeres uit Londen. Met her en der een vleugje folk horen we hier een waar natuurtalent, niet voor niets door de BBC afgelopen jaar als een van de revelaties van 2012 werd getipt. En deze belofte wordt helemaal ingelost. Leidend is haar unieke warme stem die zowel uptempo als in de langzamere songs elke emotie nauwkeurig inkleurt. En zo is elke track van een andere muzikale schoonheid met reflecterende teksten op de persoonlijke gebeurtenissen van de afgelopen jaren: onvoorwaardelijke liefde (Lost & Found), oudere mannen (Age) en relaties die over zijn (Gone). Hier is duidelijk een authentieke zangers met thought it would happen…’ Tijdens het afgelopen North een missie opgestaan die muziek gebruikt om haar Sea Jazz pakte ze iedereen met haar ontwapende gevoelens te begrijpen en te vertalen in muziek. Of verschijning en spontaniteit in; niet te missen dus voor zoals ze zelf zingt in openingstrack Is Your Love Big Lowlandsgangers! (GH) Enough: ‘Found myself in a second-hand guitar. Never 3 PoP & Rock Bestel Nu IN EEN van oNzE webwinkELS PoP & Rock THE BAmBooS medicine man S (Tru Thoughts/Tone) Pop & Rock Luister Liefhebbers van Mark Ronson, Sharon Jones & The Dapkings en Amy T Winehouse zullen deze Australische band erg weten te waarderen. -

Charing Cross Hospital Set to Close?

Still undecided? Fiery fun London to the Lakes Festival of frisbee Find out more with our general Dangerously impressive tricks It’s those Fellwanderers again, as Disc Doctors impress at south election pullout, centre pages from the jugglers, page 17 if you hadn’t guessed, page 21 east regionals, page 26 The student newspaper of Imperial College ● Established 1949 ● Issue 1320 ● Thursday 28 April 2005 ● www.felixonline.co.uk Extradition hearing Imperial alumnus Babar Union Ahmad will discover on 17 Charing Cross Hospital May whether or not he is to be extradited to the United States under new terror laws. reveals uNEWS page 3 set to close? Tackling poverty plans for “We live in a world where poverty causes the deaths of 30,000 children each day; a postgrad world where 38 million people live with HIV...” Colin Smith explains how sabbatical you can get involved in the Make Poverty History cam- By Dave Edwards paign at Imperial, while Numaan Chaudhry investi- Imperial College Union gates what the richer nations has announced ambitious are doing to address the plans for a new Sabbatical problem. Officer, the Deputy President uBUSINESS page 4 (Graduate Students). uCOMMENT page 7 Funding for the post will become available from the Poker aces Higher Education Funding Imperial students finish third Council for England and 20th out of 259 competi- (HEFCE). Within the next tors at the inaugural UK stu- two months, the Union plans dent poker championship. to elect a student who will uCLUBS AND SOCIETIES then work full-time in the page 18 role from 1 August, taking the total number of sabbaticals at Nighthike 2005 Imperial to seven. -

Reply Card [Converted]

PLEASE CAREFULLY READ THE Wii™ OPERATIONS MANUAL COMPLETELY BEFORE USING YOUR Wii HARDWARE SYSTEM, GAME DISC OR ACCESSORY. THIS MANUAL CONTAINS IMPORTANT HEALTH AND SAFETY INFORMATION. IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION: READ THE FOLLOWING WARNINGS BEFORE YOU OR YOUR CHILD PLAY VIDEO GAMES. WARNING – Seizures • Some people (about 1 in 4000) may have seizures or blackouts triggered by light flashes or patterns, and this may occur while they are watching TV or playing video games, even if they have never had a seizure before. • Anyone who has had a seizure, loss of awareness, or other symptom linked to an epileptic condition, should consult a doctor before playing a video game. • Parents should watch their children play video games. Stop playing and consult a doctor if you or your child has any of the following symptoms: Convulsions Eye or muscle twitching Altered vision Loss of awareness Involuntary movements Disorientation • To reduce the likelihood of a seizure when playing video games: 1. Sit or stand as far from the screen as possible. 2. Play video games on the smallest available television screen. 3. Do not play if you are tired or need sleep. 4. Play in a well-lit room. 5. Take a 10 to 15 minute break every hour. WARNING – Repetitive Motion Injuries and Eyestrain Playing video games can make your muscles, joints, skin or eyes hurt. Follow these instructions to avoid problems such as tendonitis, carpal tunnel syndrome, skin irritation or eyestrain: • Avoid excessive play. Parents should monitor their children for appropriate play. • Take a 10 to 15 minute break every hour, even if you don't think you need it. -

When the Party Turns Serious Gary Ryan finds Bloc Party Frontman Kele Boldly Addressing Britain’S Lost Weekends

FRIDAY 22 » CITYLIFE MUSIC FEBRUARY 9, 2007 M.E.N. When the party turns serious Gary Ryan finds Bloc Party frontman Kele boldly addressing Britain’s lost weekends ELE Okereke – well, it’s a small price to pay. A Weekend In The City opens I do think now it is time for a ness (“Asian people are skinny the reluctant star New album A Weekend In The with Song For Clay (Disappear change. We are committed to an- because they don’t cook their of Bloc Party – City is a concept record that aims Here), where Kele sings “East other album with Witchita, but food properly…” – CBB’s Jo can’t keep his to tackle the benighted state of London is a vampire/It sucks the after that who knows? I’m pretty O’Meara) that, while they might feelings corked the nation through the narrative joy right out of me’’, before sure that I will be leaving the not have used any racial epithets, any longer. of getting paralytic in the capital; sneering “live the dream like the country soon.” still highlights prejudiced behav- When the quar- from the substance-induced eu- Eighties never happened.’’ The spiky Hunting For ior.’’ tet arrived in phoria of Friday night to Sun- “With that song,” he muses, “I Witches – inspired by the after- The lure – or illusionary es- K2005 with debut Silent Alarm, day’s thoughts of suicide. was trying to describe a specific math of the 7/7 bombings – tack- cape route – of cocaine is ex- they were the wild cards of the “I wanted to make an album kind of socialite that you meet, les the tabloids’ crusade against plored in the track, On, and first art-rock pack. -

Medics' Circle Line Will Be Alcohol Free

ISSUE 1625 FRIDAY 5th FEBRUARY 2016 The Student Newspaper of Imperial College London Taking a dive into Our name is colonial – we virtual reality should change it PAGE 30 GAMES PAGE 8 COMMENT RAG mag accused of "harassment and bullying" The handout will no longer be distributed after union tells RAG it's "an unacceptable personal attack" Grace Rahman Union President. who do get to see the Mag as-is will Editor-in-Chief FELIX has seen the 16 page realise how absurd the response of handout, which is mainly adverts the Union has been”. for RAG week events, including the 500 copies of the 2000 magazines esterday the union told bungee jump, tunnel tours and the RAG printed have already been RAG its magazine of Valentine’s Ball. There are three or given out around campus. This cost adverts and satire was four pages of ‘satire’ of the union- RAG around £400. “beyond the acceptable hack variety, which (obviously) Alice Gast, the president of bounds of satire or mockery”. RAG we are unable to print here. The Imperial, who wrote a short wereY also warned that the individuals offending piece was a mock diary introduction for the magazine, said involved in writing it could be entry, reminiscent of FELIX today: "This year’s RAG Magazine faced with serious consequences Hangman’s ‘Diary of a Fresher’ is a discredit to RAG’s legacy and to from the college if they continued written from the perspective of the the College". to distribute the magazine as this Union President. "I find the mean spirited approach would be considered “elevated Its writer told FELIX they were to targeting of individuals within harassment”. -

Funeral • the Sunshine • the Shins • Natasja • TTC • Jenny

Nummer 1 • 2007 Sveriges största musiktidning Funeral • The Sunshine • The Shins • Natasja • TTC • Jenny Wilson Black Belt • Darling Kennedy • Marcus Fjellström • Karin Ström • Vienna Heat 5 The Shins 5 Tre frågor till Jenny Wilson 5 Grammis, konserter och skivskiljare 6 Funeral 6 Rock’n Roll Hall of Shame 8 Natasja topp Foto Johannes Giotas 8 Masters At Work Groove är en oberoende musiktidning som ges ut av Musiktidning i Göteborg AB. 1100 Groove 10 Blågult guld Mathias Skeppstedt, [email protected], Box 112 91 Black Belt väljer 10 låtar som knastrar, sprakar, 404 26 Göteborg berör och tar sig rakt in i magen. Darling Kennedy Låtar när du är insnöad eller regnet Telefon 031–833 855 vräker ner och det inte är nåt bra Elpost [email protected] Marcus Fjellström på tv. Plusgiro 18 49 12-4 Karin Ström Chefredaktör & ansvarig utgivare 1. sianSPHERIC – Audiphone Gary Landström, [email protected] Vienna Heat Ljuv, vacker, böljande våg av dis- torsion. Layout Henrik Strömberg, [email protected] 13 Kaiser Chiefs 2. Grinderman – No Pussy Blues Kan vara det bästa Nick Cave gjort på länge. Annonser & Groove-CD 3. Fuck Me USA – Dollars Police Cocaine Per Lundberg G.B., 15 The Sunshine Så som Suicide borde låta idag, Chris Olley och Julian [email protected], 0735–43 59 66 Cope. Groovearbetare 15 TTC 4. Shellac – End of Radio (Peel Session 2004) Therese Ahlberg Ny låt som lovar så gott, så gott. Mats Almegård Dan Andersson 16 Timbuktu 5. Future Of The Left – Fingers Become Thumbs Mikael Barani Resterna av McLusky. 1:52 minuter ren punkextas. -

Valentine's Issue 2007

Valentine’s Issue 2007 YES OR NOIn This Issue.....? YOYOU DECIDE... The Bludgeoner Tales From The Queer Side Blind Date From Bangor To Bangor News The Great Orme Travel The Adventures of Stuart Dent Music One Minute Welsh Film Adventures From Across The Pond n 30 January, Students’ Union past few years? By losing the tuition fees more than NUS affi liation. in response to avoid what was billed as a Council voted in favour of holding battle and, during the AUT “action short of a So what does Bangor specifi cally get for fi nancial crisis within NUS. But there has Puzzles Oa referendum to decide whether or strike” in 2006 (which could have prevented this money? NUS does provide extremely been no visible effort to reduce costs in not UWB Students’ Union should remain many students from graduating), supporting useful training for offi cers and students alike other areas, most notably staffi ng. NUS affi liated to the National Union of Students the AUT rather than us students. (costing an extra £3,000 per year) and we currently employ 106 staff members around Storm Forecast (NUS). Perhaps if NUS stopped wasting their stock our bars and shop through the NUSSL the country, in addition to the 29 elected I’ve always been a staunch believer time issuing press releases about Israel and buying consortium. But even then, buying offi cials who receive living allowances. in unions myself, convinced of the truth Palestine (and let’s face it, they’re hardly through the consortium only saves us £8000 No doubt you’ll be hearing much more Sport of the maxim “united we stand, divided going to drop their arms and invite each a year and we could hire a full-time trainer from both sides of this campaign in the we fall”.