132 New Zealand King Shag

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation Advice Leucocarbo Atriceps Purpurascens

THREATENED SPECIES SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Established under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 The Minister’s delegate approved this conservation advice on 01/10/2015 Conservation Advice Leucocarbo atriceps purpurascens Macquarie shag Conservation Status Leucocarbo atriceps purpurascens (Macquarie shag) is listed as Vulnerable under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cwlth) (EPBC Act). The species is eligible for listing as Vulnerable as, prior to the commencement of the EPBC Act, it was listed as Vulnerable under Schedule 1 of the Endangered Species Protection Act 1992 (Cwlth). The main factor that is the cause of the species being eligible for listing in the Vulnerable category is its small population size (250-1000 mature individuals). The Action Plan for Australian Birds 2010 considered the Macquarie shag as Vulnerable under Criterion D1 (Population 250–1000 mature individuals) (Garnett et al., 2011). The Threatened Species Scientific Committee are using the findings of Garnett et al., (2011) to consider whether reassessment of the conservation status of each of threatened birds listed under the EPBC Act is required. Description The Macquarie Shag is a medium-sized, black and white marine shag. The adult form reaches a length of 75 cm with a wingspan of 110 cm and weighs between 2.5 and 3.5 kg. (Marchant & Higgins 1990). Adult breeding birds have a glossy black top and sides of head and hindneck with a black crest on the forehead. Demarkation between the black cap and white face starts at the gape and extends back below ear-coverts leaving the lower cheeks and throat white, and giving the face a dark appearance. -

Subantarctic Islands Rep 11

THE SUBANTARCTIC ISLANDS OF NEW ZEALAND & AUSTRALIA 31 OCTOBER – 18 NOVEMBER 2011 TOUR REPORT LEADER: HANNU JÄNNES. This cruise, which visits the Snares, the Auckland Islands, Macquarie Island, Campbell Island, the Antipodes Islands, the Bounty Islands and the Chatham Islands, provides what must surely be one of the most outstanding seabird experiences possible anywhere on our planet. Anyone interested in seabirds and penguins must do this tour once in their lifetime! During our 18 day voyage we visited a succession of tiny specks of land in the vast Southern Ocean that provided an extraordinary array of penguins, albatrosses, petrels, storm-petrels and shags, as well as some of the world’s rarest landbirds. Throughout our voyage, there was a wonderful feeling of wilderness, so rare these days on our overcrowded planet. Most of the islands that we visited were uninhabited and we hardly saw another ship in all the time we were at sea. On the 2011 tour we recorded 125 bird species, of which 42 were tubenoses including no less than 14 forms of albatrosses, 24 species of shearwaters, petrels and prions, and four species of storm- petrels! On land, we were treated to magical encounters with a variety of breeding penguins (in total a whopping nine species) and albatrosses, plus a selection of the rarest land birds in the World. Trip highlights included close encounters with the Royal, King and Gentoo Penguins on Macquarie Island, face-to-face contact with Southern Royal Albatrosses on Campbell Island, huge numbers of Salvin’s and Chatham Albatrosses -

Influences of Morphology and Behavior on Wing-Molt Strategies in Seabirds

Bridge: InfluencesContributed on wing-molt Papers strategies in seabirds 7 INFLUENCES OF MORPHOLOGY AND BEHAVIOR ON WING-MOLT STRATEGIES IN SEABIRDS ELI S. BRIDGE University of Memphis, Department of Biology, 201 Life Sciences, 3774 Walker Avenue, Memphis, Tennessee, 38152, USA ([email protected]) Received 28 December 2005, accepted 5 September 2006 SUMMARY BRIDGE, E.S. 2006. Influences of morphology and behavior on wing-molt strategies in seabirds. Marine Ornithology 34: 7–19. This review formally tests several widely held assumptions regarding the evolution of molting strategies. I performed an extensive literature review of molt in seabirds, extracting information on the pattern, duration and timing (relative to breeding and migration) of molt for 236 species of seabirds in three orders: Procellariiformes, Pelecaniformes, and Charadriiformes. I used these data to test three hypotheses relating to the evolution of wing-molt strategies in seabirds: (1) that complex molt patterns are more likely to occur in large birds; (2) that wing size is an important determinant of the duration of molt; (3) that non-migratory species are more likely to overlap breeding and molt. By applying traditional and phylogenetic comparative techniques to these data, I found support for all three hypotheses in at least one major seabird group. I hope that this review will serve as a guidepost for future molt-related studies of seabirds. Key words: Molt, moult, life history, tradeoff, comparative studies, breeding, migration, seabirds INTRODUCTION Wing-molt strategies can be considered as a combination of three A basic determinant of fitness entails the allocation of resources variables: (1) pattern: the sequence in which feathers are replaced; among various activities involved in survival and reproduction. -

Trainee Bander's Diary (PDF

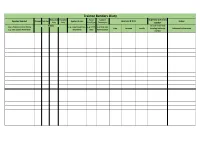

Trainee Banders Diary Extracted Handled Band Capture Supervising A-Class Species banded Banded Retraps Species Groups Location & Date Notes Only Only Size/Type Techniques Bander Totals Include name and Use CAVS & Common Name e.g. Large Passerines, e.g. 01AY, e.g. Mist-net, Date Location Locode Banding Authority Additional information e.g. 529: Superb Fairy-wren Shorebirds 09SS Hand Capture number Reference Lists 05 SS 10 AM 06 SS 11 AM Species Groups 07 SS 1 (BAT) Small Passerines 08 SS 2 (BAT) Large Passerines 09 SS 3 (BAT) Seabirds 10 SS Shorebirds 11 SS Species Parrots and Cockatoos 12 SS 6: Orange-footed Scrubfowl Gulls and Terns 13 SS 7: Malleefowl Pigeons and Doves 14 SS 8: Australian Brush-turkey Raptors 15 SS 9: Stubble Quail Waterbirds 16 SS 10: Brown Quail Fruit bats 17 SS 11: Tasmanian Quail Ordinary bats 20 SS 12: King Quail Other 21 SS 13: Red-backed Button-quail 22 SS 14: Painted Button-quail Trapping Methods 23 SS 15: Chestnut-backed Button-quail Mist-net 24 SS 16: Buff-breasted Button-quail By Hand 25 SS 17: Black-breasted Button-quail Hand-held Net 27 SS 18: Little Button-quail Cannon-net 28 SS 19: Red-chested Button-quail Cage Trap 31 SS 20: Plains-wanderer Funnel Trap 32 SS 21: Rose-crowned Fruit-Dove Clap Trap 33 SS 23: Superb Fruit-Dove Bal-chatri 34 SS 24: Banded Fruit-Dove Noose Carpet 35 SS 25: Wompoo Fruit-Dove Phutt-net 36 SS 26: Pied Imperial-Pigeon Rehabiliated 37 SS 27: Topknot Pigeon Harp trap 38 SS 28: White-headed Pigeon 39 SS 29: Brown Cuckoo-Dove Band Size 03 IN 30: Peaceful Dove 01 AY 04 IN 31: Diamond -

New Zealand Subantarctic Islands 12 Nov – 4 Dec 2017

New Zealand Subantarctic Islands 12 Nov – 4 Dec 2017 … a personal trip report by Jesper Hornskov goodbirdmail(at)gmail.com © this draft 24 Jan 2018 I joined the 2017 version of the Heritage Expedtion ‘Birding Down Under’ voyage – The official trip reports covering this and five others are accessible via the link https://www.heritage-expeditions.com/trip/birding-downunder-2018/ … and I heartily recommend reading all of them in order to get an idea of how different each trip is. While you are at it, accounts of less comprehensive trips are posted elsewhere on the Heritage Expedition website, e g https://www.heritage-expeditions.com/trip/macquarie-island-expedition-cruise- new-zealand/ The report is written mostly to help digest a wonderful trip, but if other people – Team Members as well as prospective travelers – enjoy it, find it helpful, or amusing, then so much the better… Itinerary: 12 Nov: arrived Invercargill after a journey that saw me leave home @08h00 GST + 1 on 10th… To walk off the many hours spent on planes and in airports I grabbed a free map at the Heritage Expedition recommended Kelvin Hotel and set out on a stroll - did Queen’s Park 19h05-20h15, then walked on along Queen’s Drive skirting the SE corner of Thomson’s Bush (an attractive patch of native forest which it was, alas, too late in the day to explore) and back to town along the embankment of Waihopai river as it was getting dark. Back at hotel 21h45 & managed to grab a trendy pita bread for dinner just before the joint closed. -

The Subantarctic Islands of New Zealand & Australia

We had some amazing wildlife encounters during this tour, and charismatic King Penguins certainly performed. (Dani Lopez-Velasco) THE SUBANTARCTIC ISLANDS OF NEW ZEALAND & AUSTRALIA 14 NOVEMBER – 2 DECEMBER 2013 LEADER: DANI LOPEZ-VELASCO Unforgettable. That´s a good way of describing our 2013 Subantarctic Islands of New Zealand & Australia cruise. With 48 species of tubenoses seen this year - an all-time record for this cruise - this is surely the ultimate seabirding experience in the World, and it´s definitely a must for any seabird enthusiastic. Quite a 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: The Subantarctic Islands of New Zealand & Australia 2013 www.birdquest-tours.com selection of rare endemics occur in these remote islands, making it an obligatory visit for the world birder, and given the sheer numbers of wildlife, absolutely stunning scenery and outstanding photo opportunities, any nature lover will also find this a magical cruise. During our epic trip, we visited a succession of famous islands, whose names most of us had heard many times and evoked remoteness and masses of seabirds, but actually never thought we would ever set foot on: the Snares; the Auckland Islands; Macquarie Island; Campbell Island; the Antipodes Islands; the Bounty Islands and the Chatham Islands. Called by Heritage Expeditions ‘Birding Down Under’, our 18-day voyage aboard the Russian oceanographic research vessel Professor Khromov (renamed Spirit of Enderby by our New Zealand tour operator) took us to a series of tiny pieces of land in the vast Southern Ocean and treated us to extraordinaire numbers of penguins, albatrosses, petrels, storm petrels and shags, as well as some of the world’s rarest land birds. -

Current Practices in the Identification of Critical Habitat for Threatened Species

Current practices in the identification of critical habitat for threatened species Abbey E Camaclang, Martine Maron, Tara G Martin, and Hugh P Possingham Supporting Information Cite manuscript as Camaclang, A. E., M. Maron, T. G. Martin, and H. P. Possingham. 2015. Current practices in the identification of critical habitat for threatened species. Conservation Biology 29:482-492. Fully formatted and published version of the manuscript available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12428 Appendix 1. Code definitions and list of covariates used in the content analysis Table A1-1. Coding scheme used in the content analysis of critical habitat documents, organized into categories based on foreshadowing questions used to guide the analysis. Codes Definitions 1. Information Type (What type of information is critical habitat identification based on?) Occurrence data: Occurrence Based primarily on the locations of known occupied habitats, where species currently occur or where they have occurred in the past Habitat features Based on the presence of particular habitat features known or predicted to be essential from previous knowledge of species ecology/life history Model-based data: Habitat quality Based on quantitative habitat models that relate species presence to habitat size and quality Spatial structure Based on spatial structure of populations and accounts for habitat connectivity and potential for recolonization of extinct patches Minimum viable population sizes Based on estimates of minimum viable population sizes and the amount of habitat area required to meet these minimum targets Spatially explicit population viability Based on predictions of extinction risks in different habitat configurations, using spatially explicit population viability analyses 2. -

Trophic Interactions Between the Patagonian Toothfish, Its Fishery, and Seals and Seabirds Around Macquarie Island

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 218: 283–302, 2001 Published August 20 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Trophic interactions between the Patagonian toothfish, its fishery, and seals and seabirds around Macquarie Island S. D. Goldsworthy1,*, X. He1, G. N. Tuck1, M. Lewis1, R. Williams2 1CSIRO Marine Research, GPO Box 1538, Hobart, Tasmania 7001, Australia 2Australian Antarctic Division, Channel Highway, Kingston, Tasmania 7050, Australia ABSTRACT: Macquarie Island is a small subantarctic island that supports a variety of breeding seabird and marine mammal populations. A fishery targeting the Patagonian toothfish Dissostichus elegenoides was established around the island in 1994. For ecological sustainable development (ESD) of the fishery, this study investigated the trophic interactions based on diet composition and annual consumption between Patagonian toothfish, its fishery, and seals and seabirds within the Macquarie Island Exclusive Economic Zone (MI-EEZ). Annual consumption rates for each predator were estimated from dietary data (mostly published sources), energetic budgets, prey energy con- tent, and population size. Results indicated little predation on toothfish by seals or seabirds, or prey competition between toothfish and other marine predators. The greatest dietary overlap with tooth- fish was with gentoo penguins (21% dietary overlap) and southern elephant seals (19%). These over- laps in diet were small relative to those among fur seals (3 species, ≥90%), giant petrels (84%), royal and rockhopper penguins (65%), and king and royal penguins and fur seals (>60%). The total annual prey biomass consumed by seabirds, seals, toothfish and the fishery within the MI-EEZ was esti- mated to be 419 774 t, with the greatest consumption in January, at 2779 t d–1. -

Survey Guidelines for Australia's Threatened Birds

Survey guidelines for Australia’s threatened birds Guidelines for detecting birds listed as threatened under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 i Disclaimer The views and opinions contained in this document are not necessarily those of the Australian Government. The contents of this document have been compiled using a range of source materials and while reasonable care has been taken in its compilation, the Australian Government does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this document and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of or reliance on the contents of the document. © Commonwealth of Australia 2010 This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Attorney General’s Department, Robert Garran Offices, National Circuit, Barton ACT 2600 or posted at www.ag.gov.au/cca. An erratum was added to page 131 in April 2017. AcknowledgementS This report was prepared by Michael Magrath, Michael Weston, Penny Olsen and Mark Antos, and updated in 2008 by Ashley Herrod. We are grateful to Birds Australia’s Research and Conservation Committee, which attended a workshop on survey standards and reviewed this document: Barry Baker, John Blyth, Allan Burbidge, Hugh Ford, Stephen Garnett, Henry Nix, and Hugh Possingham. -

Sub-Antarctic Islands of New Zealand Wildlife List (PDF)

Wildlife List of Sub-Antarctic Islands of New Zealand Compiled by Max Breckenridge KEY • H – Heard only • L – Leader only • I – Introduced species • E – Species is endemic to New Zealand • M – Species is endemic to Macquarie Island • e – Species is endemic to Australasia (Australia, New Zealand, New Guinea, Oceania) • ssp – subspecies • NZ – New Zealand BIRDS Species total: 116 Heard only: 1 Leader only: 3 KIWIS E (Apterygidae) Southern Brown Kiwi E (Apteryx australis) – Single heard by some, and seen by others, on Ulva Island. Typically a nocturnal species. DUCKS, GEESE & WATERFOWL (Anatidae) Canada Goose I (Branta canadensis) – Tens in Dunedin, Te Anau, and Glentanner. Black Swan e (Cygnus atratus) – Hundreds in Dunedin Harbour and Lake Dunstan. Paradise Shelduck E (Tadorna variegata) – Tens/singles around Dunedin, Oban, and hundreds at Lake Dunstan. Blue Duck E (Hymenolaimus malacorhynchos) – Single seen briefly from the bus window between Milford Sound and Te Anau. Pacific Black Duck L (Anas superciliosa) – Three birds at Milford Sound. Some likely hybrids also observed near Twizel. Mallard I (Anas platyrhynchos) – Tens/singles on several occasions. Not pure Mallards. Most individuals in NZ are hybrids with domestic varieties or Pacific Black Duck. Auckland Islands Teal E (Anas aucklandica) – At least five individuals observed at Enderby Island along the shoreline and amongst ribbon kelp. A confiding pair of this flightless endemic greeted us at our beach landing. Campbell Islands Teal E (Anas nesiotis) – Great views of a confiding individual waiting for us at the dock on Campbell Island. New Zealand Scaup E (Aythya novaeseelandiae) – Singles at Lake Te Anau and tens around Queenstown and Twizel. -

Avibase Page 1Of 30

Avibase Page 1of 30 Col Location Date Start time Duration Distance Avibase - Bird Checklists of the World 1 Country or region: Australia 2 Description includes outlying islands (Macquarie, Norfolk, Cocos Keeling, 3 Christmas Island, etc.) 4 Number of species: 986 5 Number of endemics: 359 6 Number of breeding endemics: 8 7 Number of globally threatened species: 83 8 Number of extinct species: 6 9 Number of introduced species: 28 10 Date last reviewed: 2016-12-09 Recommended citation: Lepage, D. 2019. Checklist of the birds of Australia. Avibase, the world bird database. Retrieved from .https://avibase.bsc- eoc.org/checklist.jsp?lang=EN®ion=au&list=ioc&format=1 [30/04/2019]. Make your observations count! Submit your data to ebird. -

Recovery Plan for Ten Species of Seabirds 2005

RECOVERY PLAN for the following Seabirds: Round Island Petrel – Pterodroma arminjoniana Herald Petrel – Pterodroma heraldica Antarctic Tern (New Zealand) – Sterna vittata bethunei Antarctic Tern (Indian Ocean) - Sterna vittata vittata Blue Petrel – Halobaena caerulea Fairy Prion (southern) – Pachyptila tutur subantarctica Heard Shag – Phalacrocorax nivalis Macquarie Shag - Phalacrocorax purpurascens Soft-plumaged Petrel – Pterodroma mollis Australian Lesser Noddy – Anous tenuirostris melanops 2005-2010 1 Background The Round Island Petrel (Pterodroma arminjoniana) and the Herald Petrel (Pterodroma heraldica) were listed as threatened species under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC) in July 2002 on the basis of recommendations from the Threatened Species Scientific Committee (TSSC). The category of listing for both species is critically endangered. The Antarctic Tern (New Zealand) (Sterna vittata bethunei) was listed as a threatened species under the EPBC Act in July 2000. The category of listing for the Antarctic Tern (New Zealand) is endangered. The Antarctic Tern (Indian Ocean) (Sterna vittata vittata), the Blue Petrel (Halobaena caerulea), the Fairy Prion (southern) (Pachyptila tutur subantarctica), the Heard Shag (Phalacrocorax nivalis), the Macquarie Shag (Phalacrocorax purpurascens), the Soft-plumaged Petrel (Pterodroma mollis) and the Australian Lesser Noddy (Anous tenuirostris melanops) were listed as threatened species under the EPBC Act in July 2000. The category of listing for these species is vulnerable. Detailed background information on the biology, population status and threats to the seabirds covered by this plan can be found at http://www.deh.gov.au/coasts/species/seabirds/index.html. The following sets out the Recovery Plan for these species. Objectives (270(2)(a)) To protect and manage the breeding and foraging habitats of the ten species covered by this plan to ensure anthropogenic threats, particularly the introduction and spread of alien flora and fauna, do not limit population growth of the species.