Mequitta Ahuja

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mequitta Ahuja

Tiwani Contemporary 16 Little Portland Street London W1W 8BP tel. +44 (0) 20 7631 3808 www.tiwani.co.uk Mequitta Ahuja Born in 1976, United States Lives and works in Baltimore MD, USA EDUCATION 2003 Masters in Fine Art, University of Illinois, Chicago IL, USA 1998 BA, Hampshire College, Amherst MA, USA SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 Notations, Tiwani Contemporary, London, UK Held, Art Brussels, Brussels, Belgium 2014 Automythography, The Dodd Contemporary Art Center, Athens, Greece 2013 Mequitta Ahuja, Thierry Golberg Gallery, New York NY, USA 2012 Mequitta Ahuja and Robert Pruitt, Bakersfield Museum of Art, Bakersfield CA, USA 2010 Trois, Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris, France 2010 Automythography II, Arthouse, Austin TX 2009 Automythography I, BravinLee Programs, New York NY, USA 2008 Flowback, Lawndale Art Center, Houston TX, USA 2007 Encounters, BravinLee Programs, New York NY, USA Tiwani Contemporary 16 Little Portland Street London W1W 8BP tel. +44 (0) 20 7631 3808 www.tiwani.co.uk 2005 Dancing on the Hide of Shere Khan, 12X12 Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago IL, USA SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2020 (Forthcoming) Riffs and Relations: African American Artists and the European Modernist Tradition, The Phillips Collection, Washington DC, USA Our Lady Parts, Mindy Solomon, Miami, FL, USA WomenXWomen: Selections from the Petrucci Family foundation collection of African- American Art Penn State, Lehigh Valley: De Long Gallery, PA, USA Community, Flint Institute of Art, Flint, MI, USA 2019 Intricacies: Fragment & Meaning, Aicon Gallery, New York, USA Let Me Tell You a Story, The Arts Club, London, UK 2018 About Face, Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town, South Africa Infinite Spaces: Rediscovering PAFA’s Permanent Collection, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia PA, USA Embodied Politic, Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago IL, USA The Art World We Want, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia PA, USA A Space for Thought, Brand New Gallery, Milan, Italy Unveiled, Creative Alliance, Baltimore MD, USA 2017 Shifting, David C. -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Mequitta Ahuja

MEQUITTA AHUJA EDUCATION 2003 MFA, University of Illinois at Chicago 1998 BA, Hampshire College, Amherst, MA SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2014 Automythography The Dodd Contemporary Art Center, Athens, GA 2013 Mequitta Ahuja Thierry Golberg Gallery, New York, NY 2012 Mequitta Ahuja and Robert Pruitt Bakersfield Museum of Art, Bakersfield, CA (2 person show) 2010 Trois Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris, France. 2010 Automythography II Arthouse, Austin, TX 2009 Automythography I BravinLee Programs, New York, NY 2008 Flowback Lawndale Art Center, Houston, TX 2007 Encounters BravinLee Programs, New York, NY 2005 Dancing on the Hide of Shere Khan 12X12, MCA, Chicago, IL GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2017 Engender, Curated by Joshua Friedman, Kohn Gallery Los Angeles, CA Shifting David C. Driskell Center, College Park, Maryland 2016 Statements Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX 2016 Champagne Life Saatchi Gallery of Art, London, UK 2016 State of the Art Minneapolis Institute of Art & Telfair Museums 2015 Sondheim Finalist Exhibition Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore 2014 State of the Art Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, AR 2014 Marks of Genius Minneapolis Institute of Art, MN 2013 Portraiture Now National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC 2013 War Baby/Love Child DePaul Art Museum, Chicago, IL 2012 The Bearden Project The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York 2012 The Human Touch The Blanton Museum of Art, Austin, TX 2012 Red Maison Particuliere, Brussels, Belgium 2011 Collected:Ritual Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, NY 2011 Drawings for the New Century Minneapolis -

July 24, 2017 Price $8.99

PRICE $8.99 JULY 24, 2017 JULY 24, 2017 4 GOINGS ON ABOUT TOWN 15 THE TALK OF THE TOWN David Remnick on the Trumps’ family drama; M.T.A. malaise; how to be a goddess; a new way to study abroad; David Lowery. LETTER FROM COLORADO Peter Hessler 20 Follow the Leader A small-town movement echoes the President. SHOUTS & MURMURS Jack Handey 27 Don’t Blame Yourself ANNALS OF TECHNOLOGY Nathan Heller 28 Mark as Read The slippery insights of e-mail. PERSONAL HISTORY Danielle Allen 32 American Inferno How a teen-ager becomes a crime statistic. PROFILES Kelefa Sanneh 42 Hat Trick George Strait’s startling consistency. FICTION Cristina Henríquez 52 “Everything Is Far from Here” THE CRITICS BOOKS Hua Hsu 56 Revisiting Bob Marley. 58 Briefly Noted James Wood 62 Joshua Cohen’s “Moving Kings.” MUSICAL EVENTS Alex Ross 66 A unique performance space in Colorado. THE THEATRE Hilton Als 68 “Pipeline.” THE CURRENT CINEMA Anthony Lane 70 “War for the Planet of the Apes,” “Lady Macbeth.” POEMS Natalie Shapero 25 “They Said It Couldn’t Be Done” John Skoyles 48 “My Mother, Heidegger, and Derrida” COVER Barry Blitt “Grounded” DRAWINGS Amy Hwang, P. C. Vey, Barbara Smaller, Edward Koren, Paul Karasik, Liana Finck, Benjamin Schwartz, Sam Gross, Edward Steed, Roz Chast, William Haefeli, Drew Dernavich, Robert Leighton, Alex Gregory SPOTS Jean Jullien CONTRIBUTORS Kelefa Sanneh (“Hat Trick,” p. 42) has Danielle Allen (“American Inferno,” been a staff writer since 2008. p. 32) is a political theorist and the James Bryant Conant University Pro- Cristina Henríquez (Fiction, p. -

Mequitta Ahuja 1998 BA, Hampshire College, Amherst, MA 2003 MFA, University of Illinois at Chicago

Mequitta Ahuja 1998 BA, Hampshire College, Amherst, MA 2003 MFA, University of Illinois at Chicago PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES 2018 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, Fellow 2015 Dora Maar Fellowship, Artist in Residence, Menerbes, France 2014 Siena Art Institute, Artist in Residence: Project Fellow, Siena, Italy 2011-12 MICA, Stewart McMillan Artist in Residence, Baltimore, MD 2009-10 Studio Museum in Harlem, Artist-in-Residence, New York, NY 2006-08 Core Program, Artist-in-Residence, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 Notations Tiwani Contemporary, London, United Kingdom 2018 Held Art Brussels, Tiwani Contemporary, Brussels, Belgium 2017 Meaningful Fictions and Figurative Tradition Sonja Haynes Stone Center, Chapel Hill, NC 2015 Automythography The Dodd Contemporary Art Center, Athens, GA 2013 Mequitta Ahuja Thierry Goldberg Gallery, New York, NY 2012 Mequitta Ahuja and Robert Pruitt Bakersfield Museum of Art, Bakersfield, CA (two-person show) 2010 Trois Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris, France. 2010 Automythography II Arthouse, Austin, TX 2009 Automythography I BravinLee Programs, NY, NY 2008 Flowback Lawndale Art Center, Houston, TX 2007 Encounters BravinLee Programs, NY, NY 2005 Dancing on the Hide of Shere Khan 12X12, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, IL SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2020 Riffs and Relations: African American Artists and the European Modernist Tradition The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC 2018 About Face Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town, South Africa For Freedom’s 50 States Initiative, Billboard -

Figurative Work by Mequitta Ahuja Opens Stone Center Fall 2017 Gallery Season

MILESTONESTHE SONJA HAYNES STONE CENTER FOR BLACK CULTURE AND HISTORY fall 2017 · volume 15 · issue 1 unc.edu/depts/stonecenter FIGURATIVE WORK BY MEQUITTA AHUJA OPENS STONE CENTER FALL 2017 GALLERY SEASON “My work is a form of tribute, analysis and intervention: tribute, out of sincere background, the pictures turn marginality into a regal condition.” She has focused her admiration for the figurative tradition; analysis, by making something vast career efforts on museum exhibitions, most notably: Portraiture Now at the Smithsonian comprehensible to both myself and to my viewers and intervention, by positioning a National Portrait Gallery, Marks of Genius at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, State woman-of-color as primary picture-maker, in whose hands the figurative tradition of the Art at Crystal Bridges, Champagne Life at the Saatchi Gallery, Global Feminisms at is refashioned” says artist Mequitta Ahuja of her work. The Stone Center will feature the Brooklyn Museum and The Bearden Project at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Her Ahuja’s paintings in its Brown Gallery this fall in an exhibition called Meaningful Fiction top priority is time in the studio which has led her to participate in artist in residence and the Figurative Tradition: The Art of Mequitta Ahuja. The exhibit opens on Thursday, programs at the Core Program, the Maryland Institute College of Art, the Studio September 14th at 7pm with a special reception and artist talk with Ahuja, and will be Museum in Harlem, the Siena Art Institute in Siena, Italy and at the Dora Maar House on display through November 22nd. in Menerbes, France. -

JAN 1 3 2015 of the City of Los Angeles

ACCELERATED REVIEW PROCESS - E Office of the City Engineer Los Angeles California To the Honorable Council JAN 1 3 2015 Of the City of Los Angeles Honorable Members: C. D. No. 13 SUBJECT: Hollywood Boulevard and Vine Street- Walk of Fame Additional Name in Terrazzo Sidewalk DICK GREGORY RECOMMENDATIONS: A. That the City Council designate the unnumbered location situated one sidewalk square easterly of and between numbered locations 11r and 11R as shown on Sheet #22 of Plan D-13788 for the Hollywood Walk of Fame for the installation of the name of Dick Gregory at 1650 Vine Street. B. Inform the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce ofthe Council's action on this matter. C. That this report be adopted prior to the date of the ceremony on February 2, 2015. FISCAL IMP ACT STATEMENT: No General Fund Impact. All cost paid by permittee. TRANSMITTALS: 1. Unnumbered communication dated January 7, 2015, from the Hollywood Historic Trust of the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce, biographical information and excerpts from the minutes of the Chamber's meeting with recommendations. City Council - 2 - C. D. No. 13 DISCUSSION: The Walk of Fame Committee of the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce has submitted a request for insertion into the Hollywood Walk of Fame the name of Dick Gregory. The ceremony is scheduled for Monday, February 2, 2015 at 11:30 a.m. The communicant's request is in accordance with City Council action of October 18, 1978, under Council File No. 78-3949. Following the Council's action of approval, and upon proper application and payment of the required fee, an installation permit can be secured at 201 N. -

Mequitta Ahuja Notations 13 April 2018 - 2 June 2018

Tiwani Contemporary 16 Little Portland Street London W1W 8BP tel. +44 (0) 20 7631 3808 www.tiwani.co.uk Mequitta Ahuja Notations 13 April 2018 - 2 June 2018 Tiwani Contemporary is pleased to present Notations - a forthcoming solo exhibition, debuting new works by Mequitta Ahuja. Mequitta Ahuja's recent work explores the currency of the figure of the artist at work in the history of European and American figurative painting. Merging the roles of artist-maker and subject, her monumental paintings depict the artist engrossed in various stages of her artistic process, often within the clearly defined architectural space of the studio. Demonstrating an interest beyond the medium itself, Ahuja's self-portraits explore multiple modes of representation, including abstraction, text, naturalism, schematic description, graphic flatness and illusion. Working across multiple modalities of representation allows the artist to fulfil her own representational needs and to ask timely questions about the power dynamics underpinning image production and art history: who does the representing, who is represented and in what manner? "My central intent is to turn the artist's self-portrait, especially the woman-of-colour's self- portrait, long circumscribed by identity, into a discourse on picture-making, past and present. This includes depicting my intimate relationship to painting - the verb and the noun, the act and the object - painting. I show my subject at work - reading, writing, handling canvases in the studio. I show the work, the mark, the assembling of marks into form, the brushstroke. In these ways, I replace the common self-portrait motif - the artist standing before the easel, with a broader portrait of the artist's activity." In Notation (2017), Ahuja depicts herself in an intimate studio scene, leaning over her desk, writing, and surrounded by a proliferation of painterly marks. -

MEQUITTA AHUJA 1976 Grand Rapids, MI Lives and Works in Baltimore, MD

MEQUITTA AHUJA 1976 Grand Rapids, MI Lives and works in Baltimore, MD Education 1998 BA, Hampshire College, Amherst, MA 2003 MFA, University of Illinois at Chicago, IL Solo Exhibitions 2018 She Alone, Brand New Gallery, Milan, IT 2017 Notations, Tiwani Contemporary, London, UK Meaningful Fictions and Figurative Tradition, The Sonja Haynes Stone Center, Chapel Hill, NC 2015 Automythography, The Dodd Contemporary Art Center, Athens, GA 2013 Mequitta Ahuja,Thierry Goldberg Gallery, New York, NY 2012 Mequitta Ahuja and Robert Pruitt,Bakersfield Museum of Art, Bakersfield, CA (two-person show) 2010 Trois, Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris, FR Automythography II, Arthouse, Austin, TX 2009 Automythography I, BravinLee Programs, New York, NY 2008 Flowback, Lawndale Art Center, Houston, TX 2007 Encounters, BravinLee Programs, New York, NY 2005 Dancing on the Hide of Shere Khan 12X12, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Chicago, IL Group Exhibitions 2018 Embodied Politic, curated by Anastasia Karpova Tinari, Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago, IL The Art World We Want, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA Unveiled, Creative Alliance, Baltimore, MD 2017 A Space For Thought, Brand New Gallery, Milan, IT American African American, Phillips, London, UK Engender, curated by Joshua Friedman, Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles, CA Lucid Dreams and Distant Visions: South Asian Art in the Diaspora, Asia Society, New York, NY Sondheim Exhibition, Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MD Automytography, Anastasia Tinari Project, Chicago, IL Face to Face, California -

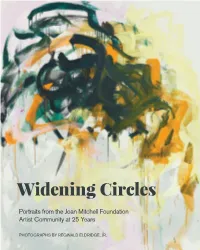

Widening Circles | Photographs by Reginald Eldridge, Jr

JOAN MITCHELL FOUNDATION MITCHELL JOAN WIDENING CIRCLES CIRCLES WIDENING | PHOTOGRAPHS REGINALD BY ELDRIDGE, JR. Widening Circles Portraits from the Joan Mitchell Foundation Artist Community at 25 Years PHOTOGRAPHS BY REGINALD ELDRIDGE, JR. Sonya Kelliher-Combs Shervone Neckles Widening Circles Portraits from the Joan Mitchell Foundation Artist Community at 25 Years PHOTOGRAPHS BY REGINALD ELDRIDGE, JR. Widening Circles: Portraits from the Joan Mitchell Foundation Artist Community at 25 Years © 2018 Joan Mitchell Foundation Cover image: Joan Mitchell, Faded Air II, 1985 Oil on canvas, 102 x 102 in. (259.08 x 259.08 cm) Private collection, © Estate of Joan Mitchell Published on the occasion of the exhibition of the same name at the Joan Mitchell Foundation in New York, December 6, 2018–May 31, 2019 Catalog designed by Melissa Dean, edited by Jenny Gill, with production support by Janice Teran All photos © 2018 Reginald Eldridge, Jr., excluding pages 5 and 7 All artwork pictured is © of the artist Andrea Chung I live my life in widening circles that reach out across the world. I may not complete this last one but I give myself to it. – RAINER MARIA RILKE Throughout her life, poetry was an important source of inspiration and solace to Joan Mitchell. Her mother was a poet, as were many close friends. We know from well-worn books in Mitchell’s library that Rilke was a favorite. Looking at the artist portraits and stories that follow in this book, we at the Foundation also turned to Rilke, a poet known for his letters of advice to a young artist. -

BMA Presents New Works by Baltimore Artists Lauren Frances Adams, Mequitta Ahuja, Cindy Cheng, and Latoya Hobbs

BMA Presents New Works by Baltimore Artists Lauren Frances Adams, Mequitta Ahuja, Cindy Cheng, and LaToya Hobbs Joan Mitchell Foundation Award Recipients Presented in Conjunction with For media in Baltimore Anne Brown Mitchell Retrospective 410-274-9907 [email protected] BALTIMORE, MD (August 18, 2021)—On November 14, the Baltimore Museum of Art For media outside (BMA) will open an exhibition of new works by Lauren Frances Adams, Mequitta Baltimore Ahuja, Cindy Cheng, and LaToya M. Hobbs. Titled All Due Respect, the presentation Alina E. Sumajin PAVE Communications explores how these Baltimore-connected artists are engaging with some of the critical & Consulting issues within our current social and political moment, including collective grief and 646-369-2050 [email protected] loss, the experience of motherhood, the legacy of the antebellum era, and the growing prevalence of conspiracy theories within our political systems. Formally and conceptually distinct, All Due Respect reflects the range of media and approaches taken by artists to examine and illuminate the impact of national histories and policies on our identities and personal and collective lives. On view through April 3, 2022, the exhibition is part of the BMA’s ongoing 2020 Vision initiative, which focuses on the achievements of women artists and leaders. All Due Respect is organized in conjunction with the much-anticipated Joan Mitchell retrospective that will open at the BMA on March 6, 2022. The four artists featured in the exhibition have been previously recognized with grants or residency awards from the Joan Mitchell Foundation, which was established by Mitchell in her will to support the changing needs and careers of working artists. -

Headlands Center for the Arts Announces 2018 Residency Awards

For immediate release HEADLANDS CENTER FOR THE ARTS ANNOUNCES 2018 RESIDENCY AWARDS 54 artists from 15 countries converge in San Francisco Bay Area to pursue cutting-edge work as part of Headlands’ annual Artist in Residence program Work by Headlands 2018 Artist in Residence awardees (clockwise from top left): Lucas Foglia, Simone Forti, Benjamin Britton, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and Ji Yeon Lim Sausalito, CA, January 30, 2018—Headlands Center for the Arts, one of the nation’s leading multidisciplinary artist residencies, today announced it has awarded fully sponsored, live-in fellowships, each with an average value of $25,000, to 54 local, national and international artists from 15 states and 15 countries. Artists will begin arriving at Headlands’ campus—a cluster of artist-rehabilitated military buildings on national park land just north of the Golden Gate Bridge in the Marin Headlands—in late February and will conduct residencies through November of 2018. Among this year’s incoming roster are emerging and established figures such as queer Muslim performance artist Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (San Francisco/Islamabad, Pakistan); interdisciplinary artist Shimon Attie (New York); painter Benjamin Britton (Athens, Georgia); photographer Hannah Collins (London); performance art luminary Simone Forti (Los Angeles), who, at 82, will use her residency to begin a new creative chapter while continuing to archive past work; new media artist and filmmaker Kahlil Joseph (Los Angeles), perhaps best known as co-director of Beyoncé’s acclaimed visual album Lemonade and for his work with The Underground Museum in Los Angeles; painter Katharine Kuharic (New York); author of four acclaimed novels and frequent contributor to The New Yorker Paul La Farge (New York); recording artist Thao Nguyen (San Francisco) of The Get Down Stay Down; conceptual artist Gala Porras-Kim (Los Angeles); architect and founder of Dosu studio Doris Sung (Los Angeles); British sculptor Richard Wentworth; social practice artist Frances Whitehead (Chicago); and conceptual artist Anicka Yi (New York).