Urban Affairs Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

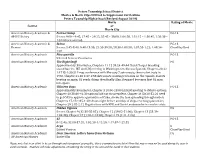

Supplemental Movies and Movie Clips

Peters Township School District Movies & Movie Clips Utilized to Supplement Curriculum Peters Township High School (Revised August 2019) Movie Rating of Movie Course or Movie Clip American History Academic & Forrest Gump PG-13 AP US History Scenes 9:00 – 9:45, 27:45 – 29:25, 35:45 – 38:00, 1:06:50, 1:31:15 – 1:30:45, 1:50:30 – 1:51:00 are omitted. American History Academic & Selma PG-13 Honors Scenes 3:45-8:40; 9:40-13:30; 25:50-39:50; 58:30-1:00:50; 1:07:50-1:22; 1:48:54- ClearPlayUsed 2:01 American History Academic Pleasantville PG-13 Selected Scenes 25 minutes American History Academic The Right Stuff PG Approximately 30 minutes, Chapters 11-12 39:24-49:44 Chuck Yeager breaking sound barrier, IKE and LBJ meeting in Washington to discuss Sputnik, Chapters 20-22 1:1715-1:30:51 Press conference with Mercury 7 astronauts, then rocket tests in 1960, Chapter 24-30 1:37-1:58 Astronauts wanting revisions on the capsule, Soviets beating us again, US sends chimp then finally Alan Sheppard becomes first US man into space American History Academic Thirteen Days PG-13 Approximately 30 minutes, Chapter 3 10:00-13:00 EXCOM meeting to debate options, Chapter 10 38:00-41:30 options laid out for president, Chapter 14 50:20-52:20 need to get OAS to approve quarantine of Cuba, shows the fear spreading through nation, Chapters 17-18 1:05-1:20 shows night before and day of ships reaching quarantine, Chapter 29 2:05-2:12 Negotiations with RFK and Soviet ambassador to resolve crisis American History Academic Hidden Figures PG Scenes Chapter 9 (32:38-35:05); -

C.A.S.E. Recommended Adoption Movies

C.A.S.E. Recommended Adoption Movies Movies Appropriate for Children: Movies Appropriate for Adults: Angels in the Outfield Admission Rear Window Anne of Green Gables Antwone Fisher Second Best Annie (both versions) Babbette’s Feast Secrets and Lies Cinderella w/Brandy & Whitney Houston Blossoms in the Dust Singing In The Rain Despicable Me Catfish & Black Bean Soldiers Sauce Despicable Me 2 Children of Paradise St. Vincent Free Willy Cider House Rules Star Wars Trilogy Harry Potter series Cinema Paradiso The 10 Commandments Kung Fu Panda (1 and 2) Citizen Kane/Zelig The Big Wedding Like Mike CoCo—The Story of CoCo The Deep End of the Lilo and Stitch Chanell Ocean Little Secrets Come Back Little Sheba The Joy Luck Club Martian Child Coming Home The Key of the Kingdom Meet the Robinsons First Person Plural The King of Masks Prince of Egypt Flirting with Disaster The Miracle Stuart Little Greystroke The Official Story Stuart Little 2 High Tide The Searchers Superman & Superman (2013) I Am Sam The Spit Fire Grill Tarzan Into the Arms of The Truman Show The Country Bears Strangers The Kid Juno Thief of Bagdad The Lost Medallion King of Hearts To Each His Own The Odd Life of Timothy Green Les Miserables White Oleander The Rescuers Down Under Lovely and Amazing Loggerheads The Jungle Book Miss Saigon Then She Found Me Orphans Immediate Family Philomena www.adoptionsupport.org . -

06 4-15 TV Guide.Indd 1 4/15/08 7:49:32 AM

PAGE 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2008 Monday Evening April 21, 2008 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With the Stars Samantha Bachelor-Lond Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY , APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS Big Bang How I Met Two Men Rules CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late KSNK/NBC Deal or No Deal Medium Local Tonight Show Late FOX Bones House Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention I Survived Crime 360 Intervention AMC Ferris Bueller Teen Wolf StirCrazy ANIM Petfinder Animal Cops Houston Animal Precinct Petfinder Animal Cops Houston CNN CNN Election Center Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Dirty Jobs Dirty Jobs Verminators How-Made How-Made Dirty Jobs DISN Finding Nemo So Raven Life With The Suite Montana Replace Kim E! Keep Up Keep Up True Hollywood Story Girls Girls E! News Chelsea Daily 10 Girls ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Fastbreak Baseball Norton TV ESPN2 Arena Football Football E:60 NASCAR Now FAM Greek America's Prom Queen Funniest Home Videos The 700 Club America's Prom Queen FX American History X '70s Show The Riches One Hour Photo HGTV To Sell Curb Potential Potential House House Buy Me Sleep To Sell Curb HIST Modern Marvels Underworld Ancient Discoveries Decoding the Past Modern Marvels LIFE Reba Reba Black and Blue Will Will The Big Match MTV True Life The Paper The Hills The Hills The Paper The Hills The Paper The Real World NICK SpongeBob Drake Home Imp. -

Advance Program Notes Powaqqatsi: Life in Transformation Philip Glass Ensemble Friday, November 1, 2013, 8 PM

Advance Program Notes Powaqqatsi: Life in Transformation Philip Glass Ensemble Friday, November 1, 2013, 8 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. CENTER FOR THE ARTS AT VIRGINIA TECH presents POWAQQATSI LIFE IN TRANSFORMATION The CANNON GROUP INC. A FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA and GEORGE LUCAS Presentation Music by Directed by PHILIP GLASS GODFREY REGGIO Photography by Edited by GRAHAM BERRY IRIS CAHN/ ALTON WALPOLE LEONIDAS ZOURDOUMIS Performed by PHILIP GLASS and the PHILIP GLASS ENSEMBLE conducted by Michael Riesman with the Blacksburg Children’s Chorale Patrice Yearwood, artistic director PHILIP GLASS ENSEMBLE Philip Glass, Lisa Bielawa, Dan Dryden, Stephen Erb, Jon Gibson, Michael Riesman, Mick Rossi, Andrew Sterman, David Crowell Guest Musicians: Ted Baker, Frank Cassara, Nelson Padgett, Yousif Sheronick The call to prayer in tonight’s performance is given by Dr. Khaled Gad Music Director MICHAEL RIESMAN Sound Design by Kurt Munkacsi Film Executive Producers MENAHEM GOLAN and YORAM GLOBUS Film Produced by MEL LAWRENCE, GODFREY REGGIO and LAWRENCE TAUB Production Management POMEGRANATE ARTS Linda Brumbach, Producer POWAQQATSI runs approximately 102 minutes and will be performed without intermission. SUBJECT TO CHANGE PO-WAQ-QA-TSI (from the Hopi language, powaq sorcerer + qatsi life) n. an entity, a way of life, that consumes the life forces of other beings in order to further its own life. POWAQQATSI is the second part of the Godfrey Reggio/Philip Glass QATSI TRILOGY. With a more global view than KOYAANISQATSI, Reggio and Glass’ first collaboration, POWAQQATSI, examines life on our planet, focusing on the negative transformation of land-based, human- scale societies into technologically driven, urban clones. -

Famous Canadians #2

Famous Canadians #2 Canada is known around the world for talented actors, singers, painters, photographers, filmmakers, fashion designers, and much more. Can you match the following Canadian talents? 1. Famous Canadian who recorded “Put Your Head on My Shoulder” ____ 2. Canadian composer who was David Letterman’s bandleader and sidekick ____ 3. Well-known hockey player and donut shop entrepreneur ____ 4. Famous Canadian who created the Superman comic character ____ 5. Best known for his long tenure on the news show 60 Minutes ____ A. Alice Munro 6. Film director of the movie Avatar ____ B. Dan Aykroyd 7. Popular French Canadian TV and radio C. Emily Carr personality ____ D. Paul Anka 8. Known for his lighthearted interview segments with children entitled Kids Say the Darndest E. Tim Horton Things ____ F. Paul Shaffer 9. Famous comedian and actor who starred in Ghostbusters and Driving Miss Daisy ____ G. Roberta Bondar 10. Painter known for her stunning images of H. Joe Shuster totem poles and landscapes ____ I. Art Linkletter 11. First Canadian woman in space ____ J. Morley Safer 12. Famous Canadian actor who starred in K. James Cameron The Truman Show and Liar Liar ____ L. Véronique Cloutier 13. Well-known Canadian author who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2013 ____ M. Jim Carrey ©ActivityConnection.com Famous Canadians #2 (solution) 1. Famous Canadian who recorded “Put Your Head on My Shoulder” D. Paul Anka 2. Canadian composer who was David Letterman’s bandleader and sidekick F. Pa u l S h a f f e r 3. -

Music in Cinema Crossword

Music in Cinema 1V A N 2N 3P G 4W 5M O R R I C O N E R E 6H I I C 7C O P L A 8N D I L C K G I E 9R A G I N G B U L L 10P R O K O F I E V 11P A R I S W H I E L A M 12S A I N T S A Ë N S Y O 13T E M P 14T R A C K T O M M D H N 15S A M F O X S O 16H E 17W A G N E R L N U E O R 18M L 19P 20S T R A N 21D 22L E I T M O T I F O I R I M R N R N M S I T G 23T T G 24A P O C A L Y P 25S E N O W O 26S H O S 27T A 28K O V I C H M N O H 29N O R T H R I E 30P L A T O O N O E N J S N R 31G 32Z 33D I E G E T I C A Y 34U N D E R S C O R I N G 35C O T Z C L T A F O Z H 36K O R N G O L D 37H A R P S L S S 38H O R N E R S E A I C I 39Z I M M E R B F O N I 40L U M I È R E P G 41A M E R I C A N 42G R A F F I T I A E E L H 43K I N G K O 44N G R A C O S 45R A S K I N S D 46S I 47A M A D E U S T G 48E A S Y R I D E R E T I C Across Down 5. -

The Truman Show: an Everyman for the Late 1990S MARGARET ROGERSON

The Truman Show: an Everyman for the late 1990s MARGARET ROGERSON In the lead-up to the Sydney opening of The Truman Show View metadata, citation and similar papers at(Paramount, core.ac.uk 1998), the film was described in a newspaper brought to you by CORE interview with its Australian director, Peter Weir,provided as by “the The University new of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals online millennium’s Everyman.”1 Just over a year after its release, Truman was in the news again when it was re-screened at the Vatican-authorized Millennium Spiritual Film Festival, a selection of films chosen on the basis of their perceived capacity to “nourish souls and edify culture.”2 The official word from the Vatican was that Jim Carrey’s character in the film was to be admired for his fight to retain his human dignity in the face of the “daunting odds” of “a technologically empowered media.” How literally are we to take the journalistic comment linking Truman and Everyman? Truman Burbank is, indeed, an “everyman” figure, “a guy whose life is a Home and Away set”,3 but what can a Hollywood movie of the late 1990s have to do with Everyman, a medieval performance text adapted into English from a Dutch source around the year 1500? How can a film that has been recognised widely as a critique of modern society and the media be aligned with a Middle English play about the process of Christian dying? Truman does not profess any religion, but can he be regarded as a secular Everyman with a spiritual message? Can the story of his recognition of, and escape from, the ever-present camera surveillance of “Seahaven” be seen to relate to Christian spirituality? The discussion that follows here takes up these issues. -

Media Questionnaire

Participant ID #: ___________________________________ Indicate 20 of the following titles that you would be able to summarize or talk about for 30 seconds: Movies 1970s: Batman Pocahontas Books: Apocalypse Now Doctor Doolittle Clockwork Orange Rush Hour Treasure Island (R. L. Stevenson) Star Wars (any) Stuart Little Lord of the Flies (William Golding) Jaws Good Will Hunting The Call of the Wild (Jack Rocky The Green Mile London) Monty Python & the Holy Grail 101 Dalmatians Charlotte’s Web (E.B. White) Grease Dumb and Dumber Oliver Twist (Charles Dickens) Halloween The Truman Show A Tale of Two Cities (Charles Willy Wonka & Choc. Factory Wild Wild West Dickens) Alien Don Quixote (Cervantes) Blazing Saddles Movies of the 2000s: Alice’s Adventures in Carrie Wonderland (Lewis Carroll) Nineteen-Eighty Four (George The Lord of the Rings Orwell) Movies 1980s: Batman To Kill a Mockingbird (Harper Bourne Identity Lee) ET Almost Famous Of Mice and Men (John Steinbeck) Raiders of the Lost Ark Finding Nemo The Lion the Witch and the The Terminator There Will Be Blood Wardrobe (C.S. Lewis) Die Hard Gladiator Moby Dick (Herman Melville) The Princess Bride Up Harry Potter (J.K. Rowling) Fast Times at Ridgemont High Shrek The Hunger Games (Suzanne Gremlins The Incredibles Collins) Back to the Future Avatar Romeo and Juliet (Shakespeare) Rain Man Spider Man A Christmas Carol (Charles Karate Kid Super Troopers Dickens) The Little Mermaid The Aviator Top Gun X-Men TV Shows: Field of Dreams Blood Diamond Ghostbusters Zoolander Full House The Breakfast Club The Prestige House of Cards Caddyshack The Notebook The Walking Dead Ferris Bueller’s Day Off Mean Girls Game of Thrones Pirates of the Caribbean Arrow Movies of 1990s: Pride and Prejudice The Big Bang Theory Harry Potter Supernatural Titanic Monsters, Inc. -

101 Films for Filmmakers

101 (OR SO) FILMS FOR FILMMAKERS The purpose of this list is not to create an exhaustive list of every important film ever made or filmmaker who ever lived. That task would be impossible. The purpose is to create a succinct list of films and filmmakers that have had a major impact on filmmaking. A second purpose is to help contextualize films and filmmakers within the various film movements with which they are associated. The list is organized chronologically, with important film movements (e.g. Italian Neorealism, The French New Wave) inserted at the appropriate time. AFI (American Film Institute) Top 100 films are in blue (green if they were on the original 1998 list but were removed for the 10th anniversary list). Guidelines: 1. The majority of filmmakers will be represented by a single film (or two), often their first or first significant one. This does not mean that they made no other worthy films; rather the films listed tend to be monumental films that helped define a genre or period. For example, Arthur Penn made numerous notable films, but his 1967 Bonnie and Clyde ushered in the New Hollywood and changed filmmaking for the next two decades (or more). 2. Some filmmakers do have multiple films listed, but this tends to be reserved for filmmakers who are truly masters of the craft (e.g. Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick) or filmmakers whose careers have had a long span (e.g. Luis Buñuel, 1928-1977). A few filmmakers who re-invented themselves later in their careers (e.g. David Cronenberg–his early body horror and later psychological dramas) will have multiple films listed, representing each period of their careers. -

Musik Und Fiktionalitätsebenen in the TRUMAN SHOW Guido Heldt (Bristol)

Kieler Beiträge zur Filmmusikforschung, 4, 2010 / 104 His master’s voice: Musik und Fiktionalitätsebenen in THE TRUMAN SHOW Guido Heldt (Bristol) THE TRUMAN SHOW bietet jede Menge an großen und ernsten Themen und Lesarten: Kritik am Reality–TV und an den modernen Massenmedien allgemein, sowohl an den Machern wie am Publikum, eine religiöse Allegorie oder eine auf Vater–Sohn–Beziehungen, eine Reflexion über das Verhältnis von Autor und fiktionaler Figur oder eine über die soziale und institutionelle Kontrolle unseres alltäglichen Lebens… Aber es ist auch ein Film über die Freude am Spiel mit filmischen Strukturen, in diesem Falle das Spiel mit den Strukturen filmischer Erzählung resp. mit den Ebenen von Fiktionalität, die jedem fiktionalen Text inhärent sind. Beide Elemente, thematischer Ernst und formales Spiel, sind dicht ineinander verwoben. THE TRUMAN SHOW (1998, Regie Peter Weir) erzählt die Geschichte von Truman Burbank (gespielt von Jim Carrey). Truman ist der erste Mensch, der in einer Fiktion geboren wurde und aufgewachsen ist – in der Fernsehserie 'THE TRUMAN SHOW', die um ihn herum konstruiert wurde. Zu dem Zeitpunkt, an dem wir ihn treffen, ist er verheiratet, hat ein Haus und einen Job im hübschen kleinen Küstenstädtchen Seahaven, und für ihn ist das die Welt. Alle um ihn herum jedoch, einschließlich seiner Frau und seines besten Freundes, sind Schauspieler; alle sind Teil der großen Maschine, die läuft, um die Illusion ihrer eigenen Realität in Trumans Bewusstsein aufrechtzuerhalten und um Trumans Leben einen für das Fernsehpublikum dramatisch befriedigenden Verlauf zu geben. Die Filmhandlung setzt ein, wenn Dinge schiefzugehen beginnen, wenn Risse in der Fassade auftauchen – ein Studioscheinwerfer, der vom ‘Himmel’ vor Trumans Füße fällt, ein Autoradio, das Truman statt des gewöhnlichen Programms die Durchsagen aus dem Kontrollraum des Studios hören lässt usw. -

Behind-The-Screens-Transcript.Pdf

MEDIA EDUCATION FOUNDATIONChallenging media TRANSCRIPT BEHIND THE SCREENS HOLLYWOOD GOES HYPER-COMMERCIAL BEHIND THE SCREENS Hollywood Goes Hyper-commercial Directors: Matt Soar & Susan Ericsson Producer: Matt Soar Editor: Susan Ericsson Executive Producer: Sut Jhally Featuring interviews with: Susan Douglas University of Michigan Bob McChesney University of Illinois Eileen Meehan University of Arizona Mark Crispin Miller New York University Jeremy Pikser Screenwriter, Bulworth Janet Waskow University of Oregon Media Education Foundation © MEF 2000 2 INTRODUCTION [Movie: Fallen] -- Budweiser’s good for me. -- Budweiser? – Yeah. -- Good. -- No, no, no, we’re going imported here. You can’t afford that. -- Budweiser. – OK. -- Have a Bud Ice, or a Bud Dry. – It is just a Bud! JANET WASKO: It seems that Hollywood is indeed becoming rapidly another advertising medium. [Movie: Other People’s Money] Is there a Dunkin Donuts in this town? MARK CRISPIN MILLER: Advertising is a form of propaganda. We must never forget this. Propaganda makes one point repeatedly. [Movie: The Firm] Grab a Red Stripe out of the fridge. MARK CRISPIN MILLER: Repeatedly. [Movie: Murphy’s Romance] Can I have two Extra Strength Tylenol and a glass of water, please? MARK CRISPIN MILLER: Repeatedly. [Movie: Mystery Men] Is it true that you lost your Pepsi endorsement? BOB MCCHESNEY: When you look at the ways movies are made today you almost should be in the aisles of a supermarket they are so closely connected with selling products. [Movie: Independence Day] See that Coke can on top of the alien craft? SUSAN DOUGLAS: When advertising and marketing are the defining logic of an age it affects everything including the movies. -

~Lag(8Ill BAM 2000 Spring Season Is Sponsored by B~ ~L1 Snri Og Sp;:),On

March 2000 Brooklyn Academy of Music 2000 Spring Season BAMcinematek Brooklyn Philharmonic 651 ARTS Saint Clair Cemin, L'lntuition de L'lnstant, 1995 ~lAG(8Ill BAM 2000 Spring Season is sponsored by B~ ~L1 Snri og Sp;:),on Brooklyn Academy of Music Bruce C. Ratner Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins Joseph V. Melillo President Executive Producer in association with Pomegranate Arts Inc. presents Philip on Film Running times: BAM Howard Gi lman Opera House Anima Mundi & Anima Mundi & Music for Film March 21, 2000, at 7:30pm Music for Film will Koyaanisqatsi/Live! March 22, 2000, at 7:30pm run for approximately Powaqqatsi/Live! March 23 & 24, 2000, at 7:30pm 90 minutes, with one Dracula: The Music and Film March 25, 2000, at 7:30pm & 20-minute intermis March 26, 2000, at 3pm sion; Koyaanisqatsi will run for approxi Original Music by Philip Glass mately 85 minutes, with no intermission; Performed by Philip Glass Powaqqatsi will run and the Philip Glass Ensemble: Lisa Bielawa , Dan Dryden , for approximately Jon Gibson , Philip Glass , Richard E. Peck Jr., Michael Riesman , 102 minutes, with no Eleanor Sandresky, & Andrew Sterman intermission; Dracula: The Music and Film with guest musicians will run for approxi Frank Cassara , Alexandra Montano, Valerie Naranjo, & Peter Stewart mately 80 minutes, with no intermission. Sound Design Kurt Munkacsi Musical Director Michael Riesman Production Management Pomegranate Arts, Inc. 17 Philip on F;ilm For the Philip Glass Production Stage Manager Doug Witney Ensemble Live Monitor Mix Steve Erb Assistant Sound Engineer Kevin Reilly Music Production Euphorbia Productions Music Publishing Dunvagen Music Publishing Press Representation Annie Ohayon Media Philip Glass and the Ensemble wish to thank Ladd Temple, Uoyd Trammel, John Fera, and the Peavey Corporation for their generous support and the use of the DPMC8X keyboards.