1 Section I. Educator Pipelines and Development 2 3 A. Needs Assessment 4 An evaluation of leadership and development systems and structures at Brookfield identified 5 gaps between the way things are, and the way we want them to be. The following needs for 6 improvement were prioritized as being highest leverage for impacting student learning. 7 Teacher Collaboration Time. The current status of teacher collaboration time is 8 one of grade level inconsistency. Some grade levels teams do engage in collaborative 9 practices; however there may be a lack of regularity. The desired state is one of well- 10 defined and consistently implemented collaboration systems and structures that build 11 ongoing formal and informal professional learning. Successful collaboration will 12 cultivate a dynamic professional community that regularly evaluates progress against 13 goals for student learning. There is a need for an increased and sufficient amount time 14 to be allocated to support effective instructional change. We are exploring a schedule 15 that frees up Wednesday minimum days for 2.5 hours of PD and PLC time. There is a 16 need for teachers to learn how to do run PLCs so they are focusing on the right work 17 and asking the right questions. Staff has expressed the need for “planning time during 18 school for lessons and collaboration and implementation of plan and review of student 19 progress,” as well as “time to plan lesson with grade level teams in order to get in 20 unison across the curriculum (i.e. familiarity of new curriculum and exchange ideas).” 21 Leadership Team. Currently, there is not an active Instructional Leadership 22 Team. The desire is for a Leadership Team that meets regularly and helps to build the 23 capacity of teachers to promote and build a culture of accountability, collaboratively use 24 data driven cycles of inquiry to improve curriculum and pedagogy, and monitor student 25 performance and progress. The Leadership Team needs to be re-chartered with a clear 26 charge, composition, expectations, responsibilities and buy-in for continuous 27 improvement toward the shared vision. Some needs described by teachers1 that an ILT 28 could provide leadership in addressing include: 1) development of grade level and 29 school-wide norms for key instructional strategies in academic discourse, engagement 30 and writing; 2) creation of school-wide norms for documentation and agenda-building in 31 PLCs; 3) establishment of consistent and coherent expectations regarding posting and 32 monitoring of grade and class level goals. 33 Teacher Recognition. At present, teacher recognition is performed by the 34 Principal through directly expressed verbal appreciation, acknowledgements in 35 newsletters, emails, and meetings, etc. The desired state is one where there is a 36 professional culture of collaboration and collegiality so all staff members recognize,

1 1 Brookfield Priority Strategies and Actions mapped to Classroom Practices

1 37 appreciate and learn from their colleagues’ strengths and contributions. Engagement 38 with teachers revealed the desire to create an environment where effort is 39 acknowledged, affirmations are made, contributions are validated, and suggestions and 40 ideas are recognized. Systematic teacher recognition is needed as a foundation for a 41 culture of collective responsibility where good work is recognized and contributes to 42 positive peer pressure for school improvement. In turn, a culture of collective 43 responsibility allows staff to reframe challenges and dilemmas as opportunities for 44 impactful reflection and action. 45 Teacher Coaching and Support. Coaching and support for teachers is currently 46 provided by the principal and the Common Core Teacher Leader. Coaching needs are 47 greater than current resources provide. There is a need to reconfigure coaching and 48 support systems and structures. Engagement with teachers surfaced expressed needs 49 for coaching and support with Balanced Literacy, and Readers and Writers Workshops, 50 CCSS and NGSS. Teachers articulated a need for ongoing weekly support through 51 observation, feedback and coaching from a coach or the principal. 52 53 B. Root Cause Analysis 54 Methodology. To identify the underlying causes of gaps between where we are and where we 55 want to be, we began with records from engagement processes and school improvement 56 initiatives begun in January 2014. We reviewed and analyzed the data, information, knowledge 57 and wisdom, using research techniques commonly used for data that is in the form of words (as 58 opposed to numbers). We sorted and categorized the information based on its relevance to the 59 five Quality School Development Pillars. Numerical data (such as test scores and attendance 60 data) were also analyzed against standards for performance and growth. Because the root 61 cause analysis was conducted retrospectively for this proposal up to 2 years after input, 62 observations and evidence were collected, we needed a method to work with an incomplete 63 set of information and data. In piecing together the root cause analysis, we used the analyzed 64 data by eliminating unlikely causes and drawing conclusion about the most likely explanation of 65 root causes. This is called “abductive reasoning,” a process of using existing knowledge to draw 66 conclusions, make predictions, or construct explanations that is often creative and intuitive. 67 Root cause verification will occur during the program planning year, and must determine 68 whether unlikely but actual root causes have erroneously been dismissed. 69 70 Gaps between the leadership and development systems and structures we have and the 71 systems and structures we desire are caused by: 72 Inadequate clarity, expectations and accountability for personal teacher 73 leadership (teachers setting goals and developing plans to lead themselves on their 74 professional mission) as well as positional teacher leadership (such as ILT)

2 75 School culture that lacks transparency and openness about teacher practices and 76 learning outcomes 77 Ambiguous definition of high expectations for student learning that impedes a 78 coordinated drive toward excellence 79 80 C. Goals 81 Teacher Collaboration Time Goal. Our goal is to design and implement systemic 82 structures for collaboration that are used effectively. Throughout the year, every 83 teacher will have the opportunity to participate in a PLC and collaborate with peers in 84 grade level teams and other groupings as appropriate. We will creatively explore new 85 approaches to scheduling to maximize effectiveness and productivity of teacher 86 collaboration time. For example, one possibility might be to convene twice per month 87 for a longer period, in lieu of weekly for a shorter period. The indicator for measuring 88 achievement of this goal will be teacher sign-in sheets during scheduled collaboration 89 time and evidence of PLC structures being in place. 90 Leadership Team Goal. Our goal is to have a representative leadership team that meets 91 at least twice a month. Leadership team roles and responsibilities will be documented. 92 Teachers will be a large part of decision making. Teacher surveys will be used to 93 measure progress toward achievement of this goal. 94 Teacher Recognition Goal. Our goal is to have methods in place for regularly 95 recognizing and celebrating the successes of students and staff. There will be a monthly 96 opportunity for teachers to be recognized for outstanding achievements or work, as 97 evidenced by artifacts of recognition. 98 Teaching Coaching and Support Goal. Our goal is to design and implement systems for 99 teacher coaching and feedback. Additionally, we will develop ways to provide peer 100 supports that strengthen continuing teacher capacity and provide ongoing learning and 101 development for new teachers. The principal and ILT will develop and support systems, 102 structures, and resources for formal and informal coaching and support of teachers, 103 peers, and teacher teams. The indicator for achievement of this goal will be a 104 documented plan with evidence of ongoing review and improvements to the plan. 105 106 D. Inspiration 107 Research shows that educators in schools that have embraced PLCs are more likely to 108 Take collective responsibility for student learning, help students achieve at higher levels, 109 and express higher levels of professional satisfaction (Louis & Wahlstrom, 2011). 110 Share teaching practices, make results transparent, engage in critical conversations 111 about improving instruction, and institutionalize continual improvement (Bryk, Sebring, 112 Allensworth, Luppescu, & Easton, 2010).

3 113 Improve student achievement and their professional practice at the same time that they 114 promote shared leadership (Louis et al., 2010). 115 Experience the most powerful and beneficial professional development (Little, 2006). 116 117 During teacher engagement, some teachers called for renewing cycles of inquiry begun in 2008- 118 09 with Partners in School Innovation, when the school was in Year 5 of Program Improvement. 119 Implementation of the Partners in School Innovation COI model resulted in Brookfield exiting 120 Program Improvement in 2011-12. Between 2008-09 and 2011-12, Brookfield’s API increased 121 from 686 to 762. In 2013-14, Brookfield re-entered Program Improvement. Since many staff 122 members are experienced and comfortable with this version of a continuous improvement 123 cycle that includes the typical steps of setting goals, planning, acting, assessing, and reflecting 124 and adjusting, our PLCs may return to this approach for teacher collaboration. 125 126 Non-negotiable features that have emerged as priorities for our leadership and development 127 systems and structures include: 128 PLCs are well established and institutionalized as part of the rhythm of the school. 129 Teachers work in teams to share responsibility to help all students learn essential 130 content and skills 131 Teams are provided adequate time to collaborate 132 Teams hold themselves accountable for results 133 There is clarity about the work teams need to do 134 Teams have access to resources and support they need to accomplish objectives 135 136 Inspired by the grit and resilience of our students, we recognize that those who are constantly 137 affirmed and encouraged for the hard work they do, are often the ones who continue to 138 progress despite challenges. Ricardo Semler, TED Talk speaker on employee engagement tells 139 us, “human nature demands recognition, and that without it, people lose their sense of 140 purpose and become dissatisfied, restless, and unproductive." Michael Norton of the Harvard 141 Business School notes, “Recognition is absolutely vital for us as human beings. And those 142 organizations that… have an operational model and culture that embeds recognition…are the 143 ones that are going to succeed in the 21st century.”2 Schools can build a meaningful culture by 144 providing opportunities for teachers and other staff to be recognized through a school-wide 145 initiative that reflects district, school and individual values.

2 2 Mia Mends, http://sodexoinsights.com/recognition-by-any-other-name/

4 146 Section II. Strong School Culture 147 148 A. Needs Assessment 149 An evaluation of school culture at Brookfield identified gaps between the current status and our 150 desired state. The following areas, which include both strengths and gaps, were determined as 151 high leverage priorities for school improvement. 152 Mission, Vision and Values. This is an area of strength. There was broad 153 stakeholder engagement and buy-in with the development the following mission, vision, 154 and values statements. 155 Mission: Brookfield Elementary School will be a safe, healthy, high‐quality, full 156 service community school focused on academic achievement in a STEAM 157 integrated curriculum, while serving the whole child, eliminating inequity, and 158 providing each child with excellent instruction, every day.

159 Vision: Brookfield students will find joy in a nurturing, rigorous, and intentionally 160 multicultural/ multilingual student-centered academic experience, while 161 developing the skills to ensure they are caring, fully-informed, critical thinkers 162 who are prepared for college, career, and life, and competent to compete in a 163 diverse global community.

164 Six foundational values provide strategic guidance in realizing our Mission and Vision.

165 1. High Expectations: We provide high quality learning experiences, with 166 rigor and high expectations, for all students. 167 2. Academic Excellence: We promote inquiry, discovery, and academic 168 discussion, so our students become critical thinkers and problem-solvers. 169 3. Equity: We honor and respond to the uniqueness of the whole student 170 and support all students to reach their potential as leaders and life-long learners. 171 4. Integrity & Responsibility: Students understand the difference between 172 right and wrong and take responsibility for their actions. 173 5. Accountability: Our community holds itself accountable for student 174 success and places students at the center of our work. 175 6. Family and Community Partnerships: We value and learn from the 176 diversity of our community and prioritize school-family partnerships for student 177 achievement and continuous school improvement. 178 Learning Beyond the Classroom. This is an area of developing strength in that 179 strategies and partnerships are emerging through the design process to promote 180 learning beyond the classroom. The Design Team has developed a concept for learning 181 beyond the classroom linked to a STEAM integrated curriculum. The concept involves

5 182 emerging partnerships with local nonprofit organizations and businesses. One example 183 of how the Design Team proposes to address needs in the area is by transforming the 184 asphalted areas of the Brookfield playground into healthy, clean air green space with a 185 sustainable urban forest and garden that can be used for outdoor education. A yet to be 186 filled gap exists in relation to learning beyond the classroom opportunities for 187 citizenship and leadership development. This need could be met through structures 188 such as student government, peer conflict managers, student traffic guards, 189 extracurricular music programs, etc. 190 College and Career Learning. This is also an area of emerging strength. College 191 and Career Learning will be linked to the activities and structures described above in 192 “Learning Beyond the Classroom” and through a burgeoning partnership with the 193 Airport Area Business Association (AABA). Members of the AABA include entities such 194 as the airport, airlines, auto dealers, hotels, construction companies, property 195 management and rea estate organizations, etc. that can provide opportunities for 196 career exploration in the real world. 197 Restorative Practices. There are currently no formal or defined restorative 198 practices in place at Brookfield. The desired state is one where restorative practices 199 positively influence behavior and strengthen the school community for the mutual 200 benefit of all. There is a need for restorative practices that go beyond restorative justice 201 which responds to wrongdoing. Restorative practices also include practices that 202 proactively build relationships and a sense of community to prevent conflict and 203 wrongdoing. A need exists to codify clearly articulated beliefs, systems and structures 204 for restorative practices. Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) is being 205 considered as our approach to improve school climate and culture. 206 Student Attendance. Chronic absence is a problem; however systems and 207 structures to address it are an emerging strength. Since 2011-12, Brookfield has seen a 208 generally upward trend in its chronic absence rate, similar to the trend for all OUSD 209 elementary schools. Throughout this period, however, Brookfield’s chronic absence 210 rate has been consistently higher. As of Feb 8, 2016, Brookfield’s chronic absence rate is 211 21%. Among grades, the TK/K rate is highest at 30%, mirroring national trends. The 212 chronic absence rate for students with disabilities is even higher at 35%. We need to 213 have systems and structures in place to prevent and intervene with chronic absence and 214 truancy. Our Community School Manager and Community Coordinator are currently 215 designing and piloting a prevention and intervention plan. 216 Family Partnerships and Communication. This is also an area of emerging 217 strength. Our Community School Manager and Community Coordinator are responding 218 to expressed needs from parents for increased opportunities for family partnerships and 219 improved communication. In addition to these immediate efforts, there is a need to

6 220 develop a Family Engagement Plan. This is also work to be conducted during our 221 program planning year. The Family Engagement Plan will address six areas: 1) 222 parent/caregiver education, 2) communication with parents and families, 3) parent 223 volunteering, 4) learning at home, 5) shared power and decision making, and 6) 224 community collaboration and resources. The plan will leverage and build upon existing 225 effective activities, such as Parent Cafes, Homework Help workshops for parents, and 226 Parent Volunteer work sessions. 227 228 B. Root Cause Analysis 229 Methodology. To identify the underlying causes of gaps between where we are and where we 230 want to be, we began with records from engagement processes and school improvement 231 initiatives begun in January 2014. We reviewed and analyzed the data, information, knowledge 232 and wisdom, using research techniques commonly used for data that is in the form of words (as 233 opposed to numbers). We sorted and categorized the information based on its relevance to the 234 five Quality School Development Pillars. Numerical data (such as test scores and attendance 235 data) were also analyzed against standards for performance and growth. Because the root 236 cause analysis was conducted retrospectively for this proposal up to 2 years after input, 237 observations and evidence were collected, we needed a method to work with an incomplete 238 set of information and data. In piecing together the root cause analysis, we used the analyzed 239 data by eliminating unlikely causes and drawing conclusion about the most likely explanation of 240 root causes. This is called “abductive reasoning,” a process of using existing knowledge to draw 241 conclusions, make predictions, or construct explanations that is often creative and intuitive. 242 Root cause verification will occur during the program planning year, and must determine 243 whether unlikely but actual root causes have erroneously been dismissed. 244 245 Gaps between the school culture we have and the culture we desire are caused by: 246 The lack of a vision, combined with the absence of coordinated and focused 247 efforts to birth opportunities for learning beyond the classroom have been obstacles. 248 With a vision now in place, the needs are to engage stakeholders and partners to 249 develop and realize a plan for learning beyond the classroom. 250 Lack of consistent schoolwide systems, structures and restorative practices to 251 define behavioral expectations, address positive behavior, respond to behavioral 252 infractions, and promote social emotional learning 253 Lack of sustained effort in promoting positive attendance and intervening early 254 with chronic absence 255 256 C. Goals

7 257 Learning Beyond the Classroom. Our goal is to have multiple systems for all students to 258 engage in rigorous learning beyond the classroom. We will leverage community 259 partnerships to develop STEAM related on-site outdoor learning as well as college and 260 career learning opportunities. The indicator for achievement of this goal will be artifacts 261 and evidence of programmatic implementation. 262 Restorative Practices Goal. Our goal is to use restorative practices to resolve all 263 disciplinary issues and to create a culture that reduces disciplinary issues. The principal 264 and ILT will lead a process to engage stakeholders and collaboratively develop and 265 support systems, structures, and resources for restorative practices. The indicator for 266 achievement of this goal will be written restorative practices guidelines. 267 Student Attendance Goal. Our goal is to reduce chronic absence to below 10% over the 268 next five years. This five year goal is based on an average 15% reduction per year, which 269 is one and a half times more aggressive than the district target of 10% reduction per 270 year. A chronic absence rate below 10% would bring Brookfield into the “green zone” 271 for Chronic Absenteeism in the OUSD Weekly Engagement Report. We will achieve this 272 goal by making personal phone calls when a student is absent; addressing attendance 273 needs in SST and COST, referring families to appropriate support resources as needed, 274 and celebrating good attendance. 275 276 D. Inspiration 277 Inspiration for Learning Beyond the Classroom comes from local school based gardens, 278 including Stonehurst campus, Merritt College, and Sobrante Park, and Oakland ReLeaf’s urban 279 forestry program. 280 281 Inspiration for preventing and intervening with chronic absence comes from the research based 282 strategies and approaches recommended by Attendance Works, a nationally recognized 283 organization that promotes policy and best practices to advance learning through improved 284 attendance. 285 286 Inspiration for development of our Family Engagement Plan comes from OUSD’s Family 287 Engagement Standards 288 289 290

8 291 Section III. Increased Time on Task 292 293 A. Needs Assessment 294 An evaluation of systems and structures for extended learning time at Brookfield revealed gaps 295 between the way things are, and the way we want them to be. The following needs for 296 improvement were prioritized as being highest leverage for impacting student learning. 297 Extended Day Programs and Activities. Brookfield’s after school program is 298 operated by Higher Ground, a local east Oakland community based nonprofit 299 organization that has partnered with Brookfield for many years. Each year, every after 300 school program across Oakland Unified is reviewed by an external evaluator and is 301 provided a Program Quality Assessment Performance Report. Overall, Brookfield’s after 302 school program receives consistently high marks. On a scale of 1 to 5, in the areas of 303 safe environment, supportive environment, interaction, engagement, and academic 304 climate, our Higher Ground program received an average score of 4.3 in 2013-14 and 4.6 305 in 2014-15. In both years, the lowest score awarded was in the area of academic 306 climate: 3.1 in 2013-14 and 4.1 in 2014-15. According to the evaluation reports, areas 307 of growth needed to strengthen the program’s academic climate include: encouraging 308 students to perform analytic and evaluative tasks, supporting individual learners by 309 presenting content in multiple modalities or breaking concepts down, and linking 310 academic content to students’ prior knowledge acquired through school day learning 311 and personal experience. The extended day program we desire is one embedded in a 312 strategic framework linked to specific targeted outcomes where there is continuity and 313 intentional linkage between school day and after school programs. There is a need for 314 stronger alignment between the after school program and the school day curriculum, 315 standards, and instruction to support student learning and offer additional supports to 316 struggling students. After school programs could complement and reinforce learning that 317 takes place in the classroom in ways that are more fun, engaging, and meaningful. 318 Engagement with teachers and parents lifted up the need for school-run extended day 319 programs such as morning intervention for struggling students and after school tutorial 320 support. 321 Extended Year Programs and Activities. During summer vacation, many 322 students lose knowledge and skills. Research has shown that summer learning loss 323 disproportionately affects low-income students, particularly in reading. Moreover, 324 “summer learning loss is cumulative; over time, the difference between the summer 325 learning rates of low-income and higher-income students contributes substantially to 326 the achievement gap.”3 At Brookfield, between the end of the 2014-15 school year and

3 3 McCombs, et al. Making Summer Count: How Summer Programs Can Boost Children’s Learning. 2011. Rand 4 Corporation.

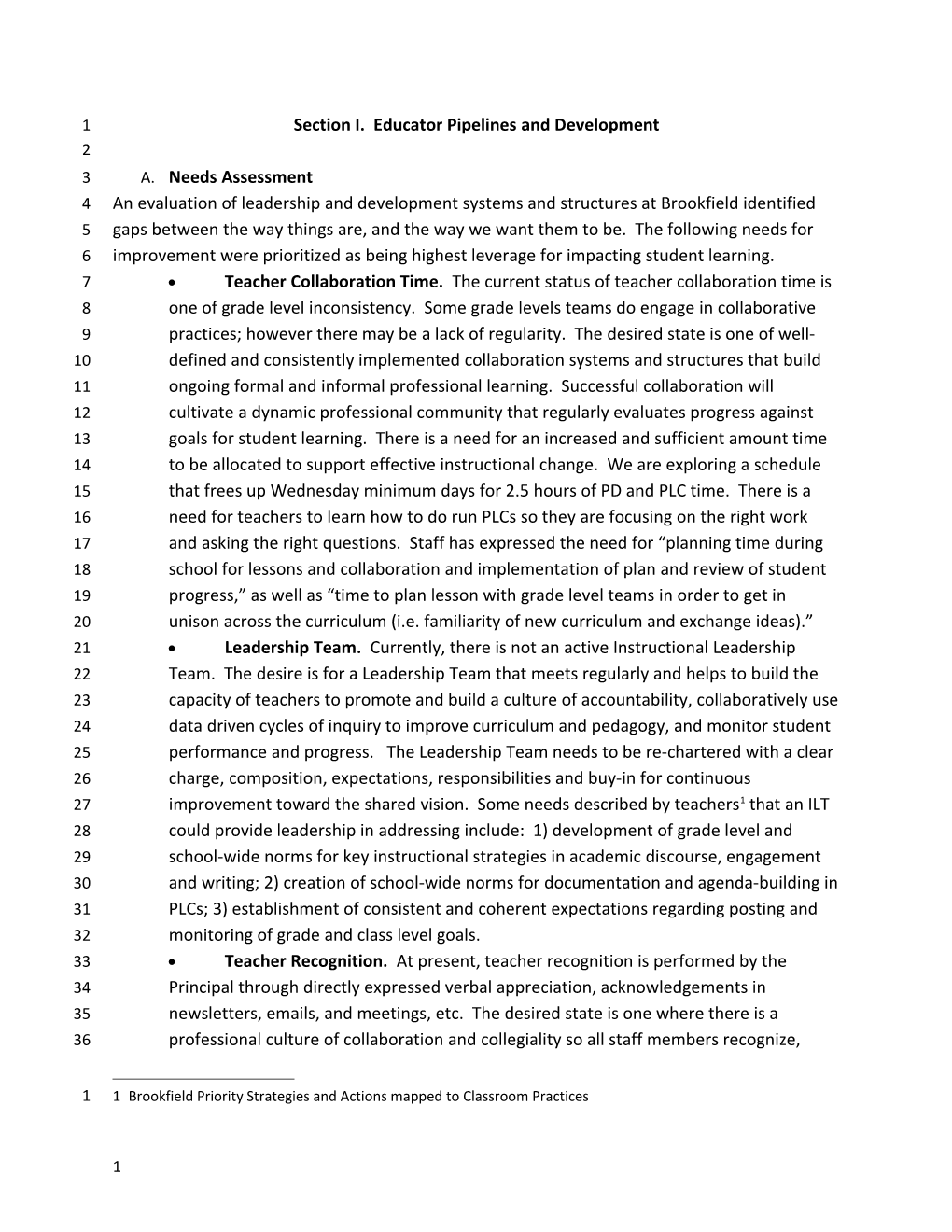

9 327 the beginning of the 2015-16 school year, over one-third of students entering grades 3, 328 4, and 5 experienced summer learning loss in reading, as indicated in the chart below. 329 With an average loss of over 100 Lexiles, students who were reading at grade level in 330 Spring 2015 mostly likely began the year reading below grade level in Fall 2015. 331 332 Summer Learning Loss 333 Brookfield: Spring 2015 to Fall 2015 2015-16 % students with Average decrease in Grade summer learning Lexiles loss1 in SRI 3 37% 140 4 42% 134 5 37% 111 334 1students whose Fall 2015 SRI scores were lower than their 335 Spring 2015 SRI scores 336 337 There is a need for high quality sustained summer programs that: 1) emphasize 338 application and enjoyment as much as learning; 2) incorporate more hands-on activities 339 and events into the curriculum; 3) align their objectives with the regular school 340 curriculum; and 4) keep class sizes small. Quality is important as research reveals that 341 “improving the quality of instructional time is at least as important as increasing the 342 quantity of time in school.”4 During summer 2016, Springboard Collaborative will 343 operate a 6 week summer session focused on accelerating reading development for 344 students currently reading below grade level. This is the first year that Springboard will 345 be offering its summer program at Brookfield. On an inconsistent basis, there have 346 been summer expanded learning opportunities offered to Brookfield students in the 347 past. Meeting the need for consistent and sustained high quality extended year 348 programs is a priority for its potential impact on our target student population. 349 350 Scheduling of core content. The Brookfield staff has become increasingly aware of time as a 351 precious resource and the need to disburse time sparingly and invest it carefully based on 352 focused learning goals and individual student needs. To increase time on task, our desire is to 353 design the most effective way for structuring the use of time and scheduling core content 354 within the day and across the year. There is a need to identify the integrated series of priority 355 practices that will work at Brookfield to optimize use of time. Such practices would address 356 analyzing data to measure student learning, targeting instruction to individual student needs, 357 managing classrooms tightly to “make every minute count,” and holding students to high

5 4 Silva, E. 2007. “On the Clock: Rethinking the Way Schools Use Time.” Education Sector. 6 http://www.educationsector.org/sites/default/files/publications/OntheClock.pdf

10 358 expectations for learning and behavior. With systems in place to maximize use of time, 359 decisions regarding scheduling of core content can be made that address duration of 360 instructional blocks, the balance among subjects and between academics and enrichment, the 361 amount of time for teacher collaboration, etc. Engagement with teachers identified the need 362 for consistent school wide scheduling of Readers Workshop and Writers Workshop to 363 systematize the time committed to literacy instruction. Also identified by teachers is the need 364 for a modified daily schedule that accommodates daily intervention built into the schedule. 365 366 B. Root Cause Analysis 367 Methodology. To identify the underlying causes of gaps between where we are and where we 368 want to be, we began with records from engagement processes and school improvement 369 initiatives begun in January 2014. We reviewed and analyzed the data, information, knowledge 370 and wisdom, using research techniques commonly used for data that is in the form of words (as 371 opposed to numbers). We sorted and categorized the information based on its relevance to the 372 five Quality School Development Pillars. Numerical data (such as test scores and attendance 373 data) were also analyzed against standards for performance and growth. Because the root 374 cause analysis was conducted retrospectively for this proposal up to 2 years after input, 375 observations and evidence were collected, we needed a method to work with an incomplete 376 set of information and data. In piecing together the root cause analysis, we used the analyzed 377 data by eliminating unlikely causes and drawing conclusion about the most likely explanation of 378 root causes. This is called “abductive reasoning,” a process of using existing knowledge to draw 379 conclusions, make predictions, or construct explanations that is often creative and intuitive. 380 Root cause verification will occur during the program planning year, and must determine 381 whether unlikely but actual root causes have erroneously been dismissed. 382 383 Gaps between our current systems and structures to increase time on task and the systems and 384 structures we need, are caused by: 385 Underdeveloped shared understanding of what it means to use time well. 386 In-progress, yet still underdeveloped planning, organizing, and structuring of 387 time that creates conditions for improved student performance. 388 Schedules that do not fully coordinate and synchronize complex demands on 389 time such as 1) time to coach and develop teachers; 2) time to teach and reinforce high 390 expectations; and 3) time to assess student understanding and analyze and respond to 391 data. 392 Insufficient network of partners for implementing or resourcing extended day or 393 extended year programs. 394 395 C. Goals

11 396 Extended Day Programs and Activities. Our goal is to have well established extended 397 school time that 1) engages students in learning activities aligned to the goals of the 398 academic day; and 2) increases learning opportunities for all students. Indicators for 399 measuring achievement of this goal could be 1) artifacts that document planning and 400 communication regarding establishment of new extended day programs and 401 refinements to existing after school program; and 2) enrollment and sign-in sheets for 402 newly established programs as well as the existing after school program. 403 Extended Year Programs and Activities. Our goal is to schedule regular, dedicated 404 teacher time for planning, collaboration, and professional learning through extended 405 time opportunities. Achievement of this goal could be measured by reviewing the 406 school’s master calendar and schedule. 407 Scheduling of Core Content. Our goals are to: 1) adopt shared agreements for 408 optimizing use of time that maximizes student performance and progress; and 2) 409 develop schoolwide practices for scheduling core content that coordinates and 410 synchronizes competing priority demands on time. Achievement of this goal could be 411 measured by artifacts that document discourse among teachers, administrator, and the 412 ILT related to time on task and the completion of core content instructional schedules. 413 414 D. Inspiration 415 Publications from the National Center on Time and Learning describing research and best 416 practices for expanded learning time were a source of inspiration for this pillar. Specifically, 417 case studies about Expanded Learning Time schools in the report entitled, “Time Well Spent,”5 418 were particularly helpful. We are considering some of the models and examples in this report 419 that are exemplars for optimizing time for student learning by: 1) making every minute count; 420 2) prioritizing time according to focused learning goals; and 3) individualizing learning time and 421 instruction based on student needs. Additional inspiration was provided by research on 422 summer learning loss and how to mitigate its negative effects. “Making Summer Count,” a 423 2011 report prepared by the RAND Corporation,6 finds evidence that summer programs can 424 help, identifies obstacles to providing them, analyzes costs, and offers recommendations. 425 426 Program Quality Assessments for the past 4 years conducted by the research firm Public Profit 427 were informative for describing the optimal academic climate for an after school program. 428

7 5 Kaplan, Claire; Chan, Roy. 2011. Time Well Spent: Eight Powerful Practices of Successful, Expanded-Time Schools. 8 Center for Time and Learning.

9 6 Jennifer Sloan McCombs, Catherine H. Augustine, Heather L. Schwartz et al. 2011. Making Summer Count: How 10 Summer Programs Can Boost Children’s Learning. RAND Corporation.

12 429 Section IV. Rigorous Academics 430 431 A. Needs Assessment 432 An evaluation of academic rigor at Brookfield identified gaps between the way things are, and 433 the way we want them to be. We aspire to create conditions for accelerated growth and high 434 levels of achievement characterized by: 1) a steadfast conviction among adults and students 435 alike that students can and will achieve at high levels, coupled with an academic push from 436 teachers to have all students progress far and attain high levels of mastery; 2) the provision of 437 instructional supports to ensure achievement, such as scaffolding, leveraging prior knowledge, 438 modeling thinking processes and strategies, intervening to bridge gaps in knowledge and skills; 439 3) a focus on the new standards with an emphasis on higher-order thinking skills, the ability to 440 use knowledge to analyze information, weigh evidence and solve complex problems. In an 441 Extended Site Visit during 2014-15, the visiting Network 3 team found that although students 442 were busy working in all classes, the rigor of given tasks was low. There was little evidence of 443 authentic reading and writing tasks for students. In whole group instruction, students were 444 called on one by one and generally gave one word answers. Similarly, Instructional Rounds 445 data revealed some evidence that structures are in place to promote academic discourse; 446 however academic discussions are inconsistently implemented across the school and most 447 conversations are teacher centered. Since then, some teachers have ratchetted-up efforts to 448 ensure that students read, talk, think, and write daily; however, school wide gaps still remain. 449 450 With respect to curricular rigor, a dominant recurring theme that emerged from engagements 451 with parents, staff, and community is the interest in expanding the school’s science focus into a 452 fully developed Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Mathematics (STEAM) curriculum. 453 The STEAM curriculum would build upon and be integrated with the school’s emerging 454 Balanced Literacy focus. Stakeholders are calling for active hands-on learning, perhaps through 455 project based learning (PBL), which allows students to demonstrate what they know and can do 456 beyond recalling facts. PBL is a particularly effective instructional approach for teaching to the 457 New Generation Science Standards (NGSS) by engaging students in the deeper thinking of 458 modeling, real world problem solving, and communicating their understanding. 459 Instructional Materials. Introduction of a STEAM integrated curriculum will require new 460 kinds of instructional materials. We will need increased and better access to technology 461 to support teaching and learning. 462 Assessment, Progress Monitoring and Use of Data. There is a need to enhance skill and 463 regularize practice among teachers regarding progress monitoring and use of data. 464 Teachers need to become self-sufficient in understanding how to analyze and use data 465 and manage technology to access it. In engagements, teachers expressed a desire for a

13 466 system and structure to analyze data, set individual student goals, and monitor results in 467 weekly PLCs through formative data cycles. 468 Teacher Collaborative Planning. There is a need to establish systems and structures for 469 teacher collaborative planning. We need clearly articulated processes, responsibilities, 470 deliverables, expected outcomes, and accountability. Cycles of inquiry need to be 471 formalized and the system established for ILT members to provide leadership. If we 472 continue to move in the direction of a STEAM integrated curriculum with hands-on 473 learning through interdisciplinary project based learning, extensive teacher 474 collaborative planning will be needed. For example, teachers would collaborate to 475 create a driving question that is tied to standards, addresses a real-world problem that 476 relates to students’ experiences and community, and inspires students to find a 477 solution. 478 Shared Expectations for Students. There is a need to establish expectations for mastery 479 for all students, with strategies and action to reteach for mastery. There is a need to 480 monitor students who are not progressing, and take steps to intervene. There is a need 481 to establish a schoolwide RTI system for students requiring additional supports. There is 482 a need to establish shared expectations of student learning as it relates to STEAM. 483 STEAM education isn't just the content; it is also the process of being scientists, 484 mathematicians, engineers, artists and technological entrepreneurs. There is a need for 485 consistent, high quality common core aligned learning outcomes and objectives, so that 486 students understand what they are learning and how it relates to long term outcomes. 487 There is a need for parents and families to understand expectations for their children’s 488 learning, and school wide expectations for student achievement. 489 Language Development. Gap analysis in the area of language development highlights 490 significant and urgent needs for English Language Learners, as well as students whose 491 home language is English. In Fall 2015, 71% of Brookfield’s students entering grades 2 492 through 5 were multiple years below grade level in reading, as assessed by the 493 Scholastic Reading Inventory (SRI). Among the 41 students entering the 3rd grade, 88% 494 were multiple years below grade level on the SRI. Among the 20 students entering the 495 3rd grade who exited Brookfield’s bilingual program the previous year, 100% were 496 multiple years below grade level on the SRI. In 2015-16, a maximum of 8% of 190 ELLs 497 can be reclassified as proficient in English – about one half of our target rate of 14%. 498 There is a need to establish school wide designated and integrated ELD systems and 499 structures, and to provide professional development in ELD instruction. There is a need 500 for language instruction that provides language development throughout the curriculum 501 regardless of subject and content being taught. Students should have access to 502 language support scaffolds (sentence frames, multiple choice oral responses, diagrams 503 and other representations) to engage in learning. For ELLs, there is a need to leverage

14 504 students’ home language and cultural resources, and develop students’ translanguaging 505 skills. There is a need for bilingual teachers to provide explicit instruction on cross- 506 linguistic transfer. There is need to strengthen Tier 1 academic language instruction for 507 all students. 508 Programs for Exceptional Students. There is a need for improved systems and 509 structures to better integrate special education students into the entire school 510 community. There is a need for sensory tools like weighted vests, cube chairs, sensory 511 fidgets and a yoga-like ball to help calm special education students during instruction 512 time. These materials help all students by providing them extra sensory support when 513 they feel like their environment is becoming overwhelming. There is need for additional 514 adaptive technology. 515 516 B. Root Cause Analysis 517 Methodology. To identify the underlying causes of gaps between where we are and where we 518 want to be, we began with records from engagement processes and school improvement 519 initiatives begun in January 2014. We reviewed and analyzed the data, information, knowledge 520 and wisdom, using research techniques commonly used for data that is in the form of words (as 521 opposed to numbers). We sorted and categorized the information based on its relevance to the 522 five Quality School Development Pillars. Numerical data (such as test scores and attendance 523 data) were also analyzed against standards for performance and growth. Because the root 524 cause analysis was conducted retrospectively for this proposal up to 2 years after input, 525 observations and evidence were collected, we needed a method to work with an incomplete 526 set of information and data. In piecing together the root cause analysis, we used the analyzed 527 data by eliminating unlikely causes and drawing conclusion about the most likely explanation of 528 root causes. This is called “abductive reasoning,” a process of using existing knowledge to draw 529 conclusions, make predictions, or construct explanations that is often creative and intuitive. 530 Root cause verification will occur during the program planning year, and must determine 531 whether unlikely but actual root causes have erroneously been dismissed. 532 533 Gaps between the academics we have and the rigorous academics we desire are caused by: 534 The absence of school wide high expectations for all students and the necessary 535 grit among students and adults to accelerate achievement. 536 The absence of school wide and grade level consistency in implementation of 537 agreed upon instructional strategies, such as Readers Workshop. 538 The absence of a targeted focus on every student having individual learning 539 goals with a strategy to achieve goals, and a plan for monitoring progress. 540 Absence of a school wide system for designated ELD and a school wide 541 instructional approach to embedded integrated ELD.

15 542 543 C. Goals 544 Instructional Materials. Our goal is to ensure that teachers have access to all 545 instructional materials and resources needed to help students achieve high growth.

546 Assessment, Progress Monitoring and Use of Data. Our goal is for teachers to regularly 547 engage in data-driven inquiry cycles that support regularly assessing students and 548 analyze their progress.

549 Teacher Collaborative Planning. Our goal is for teachers to collaborate and share 550 strategies for teaching and re-teaching skills with the expectation that students master 551 standards.

552 Shared Expectations for Students. Our goal is for parents to meet with teachers at the 553 beginning of the year to set high expectations for their student’s achievement. A 554 related goal is for individualized learning plans to developed and monitored throughout 555 the year.

556 Language Development. Our goal is to implement a language development program 557 that provides all students , including ELLs, with: 1) full access to an engagement in the 558 rigorous academic demands of the curriculum; 2) designated and integrated ELD; 3) 559 instruction that ensures active student engagement; and 4) asset based and data-driven 560 instruction.

561 Programs for Exceptional Students. Our goal is for special education students to be 562 fully integrated into the school community. For mild/moderate students, our goal is for 563 them to have access to the Common Core curriculum and participate in the statewide 564 and district-benchmark testing. For moderate/severe students, our goal is for them to 565 have a consistent curriculum and instruction and a positive social-emotional climate.

566

567 D. Inspiration 568 The Common Core State Standards (CCSS), New Generation Science Standards (NGSS), and 569 California’s 2012 English Language Development Proficiency Standards provide inspiration for 570 ensuring rigorous academics at Brookfield. The new standards necessitate development of 571 critical-thinking, problem-solving, analytical and communication skills that students will need to 572 be successful in college and career. Inspiration was also derived from OUSD’s English Language 573 Learner and Multilingual Achievement Office Essential Practices and OUSD’s Programs for 574 Exceptional Children Strategic Plan.

16 575

17 576 Section V. Linked/Personalized Learning

577 A. Needs Assessment 578 An evaluation of personalized learning at Brookfield identified gaps between the current status 579 and our desired state. Brookfield is in a nascent stage of development with personalized 580 learning. Among numerous areas of needed growth, the following have been identified as 581 priority areas with the greatest potential to positively impact our students. 582 583 The long term aspiration for personalized learning is well described by OUSD’s 584 Blended/Personalized Learning Department. It will require new approaches to schooling that 585 leverage, time, talent, resources, and technology to ensure that the needs of every student are 586 met. We will strive to move in a direction where we:7 587 Start with learning goals that are broad, deep, and interdisciplinary across academic, 588 cognitive and social-emotional aims; and, hold the highest of expectations for all 589 students to meet these ambitious goals 590 Give students the freedom and power to own their learning, choosing the pace and types 591 of learning activities that work best for them, in service of their goals 592 Personalize the learning experience to meet every student based on where she is, what 593 she needs, and her goals and strengths 594 595 At present, classroom instruction at Brookfield typically follows a more traditional model of 596 instruction. There is a tendency toward a generic learning model that does not account for 597 students’ different learning preferences or unique needs. Classroom discourse tends to follow 598 the IRF sequence (teacher initiation – student response – teacher feedback), where students 599 receive and reiterate information without actively contributing to their learning. Findings from 600 the 2013-14 School Quality Review report revealed, “Overall, the team observed little evidence 601 that students at Brookfield were experiencing active and different ways of learning in the 602 classroom.” The report further notes, “In the majority of classrooms, students spent most of their 603 time listening to whole group direct instruction that was teacher centered, or working 604 independently with little direction.” We tend to offer a “one size fits all” approach to schooling in 605 which all students in a class receive the same type of instruction, the same assignments, the same 606 assessments, with little variation or modification from student to student. 607 Student Goal Setting. We aspire to create conditions wherein every student has 608 dynamic and clearly defined learning goals based on his/her individual strengths, needs, 609 and motivations. Progress toward goals would be continually assessed, and a student 610 would advance when mastery has been demonstrated. Individualized student goal 611 setting is not in common practice at Brookfield. The school is moving in this direction by

11 7 Direct quote from: https://sites.google.com/a/ousd.org/personalized-learning/home/PersonalizedLearning

18 612 improving systems and structures for continual assessment, and building capacity to 613 make meaning from assessment data. Significant gaps exist in this area. Professional 614 development and support will be needed to implement these changes. 615 Personalized Learning Plans. We aspire to create conditions wherein every student is 616 held to clear, high expectations, but in the context of a personal learning path. Each 617 student would follow a customized path that responds and adapts based on his/her 618 individual learning progress, changing needs, motivations, and goals. Personalized plans 619 might offer students varied learning experiences such as complex performance tasks 620 and/or experiential learning opportunities. A variety of modalities would also be 621 possible, including small group instruction, one-to-one tutoring, project based learning, 622 and/or online learning. Teachers would choose the right delivery method for various 623 types of content. We want to explore ways to engage students in developing their 624 learning plans, so they begin to “own” their education, which will serve them well in 625 college and career. We want to explore project based learning as a way to give students 626 personal choice and opportunities to pursue learning that reflects their personal 627 interests. Significant gaps exist in this area. The concept of individualized student goal 628 setting and progress planning has been introduced; however, uptake has not been 629 consistent. Professional development and support through PLC time will be needed to 630 establish school wide routine practice of teachers developing and monitoring 631 personalized learning plans.

632 Small Group Instruction. We aspire to create conditions wherein instruction is 633 differentiated and learning is personalized through small group instruction. Small 634 groups offer increased opportunity for academic discussion, student engagement, and 635 active learning. While whole-class lessons are useful for overviews, modeling, and quick 636 reviews, in presenting rigorous content in whole class instruction, teachers often cannot 637 closely monitor students’ response to instruction or provide explicit, real-time feedback. 638 We wish to use flexible small group lessons to enable students to access complex 639 material with teacher support and deepen their understanding before being released to 640 work independently on assignments. Online educational technology can support 641 classroom management for small group instruction by providing meaningful 642 independent learning activities for students not with the teacher. Our SSC recently 643 voted to purchase schoolwide licenses for ST Math from Title I funds. Educational 644 technology software can also support teachers with ongoing assessment and data- 645 determined creation of flexible groups. Again, significant gaps exist in this area. Small 646 group instruction is emerging in pockets of the school; however, there is a need to 647 support implementation school wide. Professional development and support will be 648 needed to realize these changes.

19 649 Strategies for Advanced Learners. We aspire to create conditions wherein personalized 650 learning takes into account the needs of students who are high achieving. Students who 651 have already demonstrated mastery would not be held back by the majority of students 652 who are still working toward mastery. Advanced learners could move forward in their 653 learning, which might mean offering enrichment opportunities within the grade level, or 654 it could mean moving on to the next set of standards. As with this entire section, 655 significant gaps exist in this area. Because there are few advanced learners, they are 656 often overlooked, and their needs are often not met. Professional development and 657 support will be needed to implement these changes. 658 659 B. Root Cause Analysis 660 Methodology. To identify the underlying causes of gaps between where we are and where we 661 want to be, we began with records from engagement processes and school improvement 662 initiatives begun in January 2014. We reviewed and analyzed the data, information, knowledge 663 and wisdom, using research techniques commonly used for data that is in the form of words (as 664 opposed to numbers). We sorted and categorized the information based on its relevance to the 665 five Quality School Development Pillars. Numerical data (such as test scores and attendance 666 data) were also analyzed against standards for performance and growth. Because the root 667 cause analysis was conducted retrospectively for this proposal up to 2 years after input, 668 observations and evidence were collected, we needed a method to work with an incomplete 669 set of information and data. In piecing together the root cause analysis, we used the analyzed 670 data by eliminating unlikely causes and drawing conclusion about the most likely explanation of 671 root causes. This is called “abductive reasoning,” a process of using existing knowledge to draw 672 conclusions, make predictions, or construct explanations that is often creative and intuitive. 673 Root cause verification will occur during the program planning year, and must determine 674 whether unlikely but actual root causes have erroneously been dismissed. 675 676 Gaps between our current systems and structures for personalized learning and the systems 677 and structures we need, are caused by: 678 Relative newness of personalized learning in OUSD, and an undeveloped shared 679 understanding of personalized learning, and how it is implemented 680 The absence of a shared belief that individual learning goals for every student, 681 along with strategies to achieve goals, and a plans for monitoring progress are beneficial 682 Lack of familiarity with competency based learning. Although teachers recognize 683 that not all students learn at the same pace, they have not embraced the notion of 684 mastery of knowledge and skills as a better measure of learning than time on task. 685 Lack of accountability and transparency regarding high expectations and 686 academic achievement for all students.

20 687 688 C. Goals 689 Student Goal Setting. Our immediate goal is to introduce implementation of data- 690 driven student goal setting and progress monitoring in at least one subject area 691 schoolwide. Over time, we hope to develop personalized learning to the point that, 692 within the context of the student’s plan, students self-direct their learning with control 693 over their own time, place, path, and/or pace.

694 Personalized Learning Plans. Our immediate goal is to introduce a degree of 695 personalized learning such that all students have personalized learning plans that 696 includes goals for mastery in some content areas. In this transitional stage, we will 697 begin to use digital data (e.g., data from adaptive Ed tech programs) along with 698 classroom data to understand formative progress, and to create differentiated student 699 groupings.

700 Small Group Instruction. Our immediate goal is for every student to spend some time 701 each week in differentiated small group instruction and in collaborative student groups. 702 Over time, our goal is for small group instruction to become an integral part of daily 703 instruction; teachers will have various grouping protocols (e.g., whole class, small group, 704 online) with some student choice. Student to student/teacher collaboration can happen 705 anytime. Teacher will have shifted from a primarily expert role to a primarily coach and 706 facilitator role.

707 Strategies for Advanced Learners. Our goal is for the needs of advanced learners to be 708 met through systematic instructional differentiation and personalized learning as 709 describe above.

710 711 D. Inspiration 712 One source of inspiration comes from Oakland’s Next Generation Learning Challenge (NGLC) 713 sponsored by the Rogers Family Foundation. Six public schools in Oakland, including both 714 district and charter schools, wrote school design blueprints for implementing personalized 715 learning. These design proposals provide detailed descriptions of how personalized learning 716 could work in Oakland. The NGLC website also provides a wealth of general resources including 717 a framework for understanding personalized learning. Rocketship Charter Schools, Milpitas 718 Unified School District, an Education for Change ASCEND K-8 school provided examples of 719 technology enhanced models of personalized learning in practice. OUSD’s Personalized 720 Learning Google site provided additional inspiration. The website describes technology enabled 721 learning, blended learning, and personalized learning, with information about supporting 722 schools and teachers to make the shift from traditional practices.

21 723 Section VI. Facilities and Configuration 724 725 A. Configuration 726 We are proposing to maintain Brookfield’s current grade level configuration, which is pre- 727 kindergarten to fifth grade. Our Pre-K program consists of a morning and afternoon session of 728 half-day state preschool. Pre-K and TK programs are critical to counteract the negative effect of 729 poverty on Kindergarten readiness and ensure students do not fall behind during their first year 730 of school. From Pre-K to fifth grade, we will provide a strong foundation to prepare students 731 for their transition to middle school. 732 733 B. Facility Modifications / Improvement 734 Modifications or improvements that may be integral to the proposed program include: 735 Creation of a technology lab that is larger than a typical classroom for implementation 736 of blended learning 737 Improvement and expansion of the school library into a community learning center with 738 community access 739 Creation of smaller learning spaces for intervention and tutorials 740 Modifications to student bathrooms that will allow us to physically cluster classrooms by 741 grade level 742 The proposal team is considering the transformation of existing outdoor space into an urban 743 forest and learning gardens, with an Environmental Protection Agency experimental clean air 744 buffer between I-880 and our playground and school. The urban forest and gardens would 745 become learning spaces for our STEAM curriculum, focusing on outdoor education, life science, 746 and environmental science. Removal of asphalt would be required.

22