The War Within

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 4, 2020 Check Your Local TV Listings to Find the Channel for Your Local PBS Station

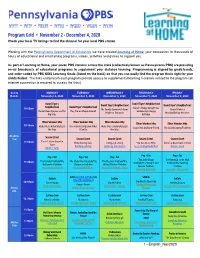

Program Grid • November 2 - December 4, 2020 Check your local TV listings to find the channel for your local PBS station. Working with the Pennsylvania Department of Education, we have created Learning at Home, your connection to thousands of hours of educational and entertaining programs, videos, activities and games to support you. As part of Learning at Home, your seven PBS stations across the state (collectively known as Pennsylvania PBS) are providing on-air broadcasts of educational programs to supplement your distance learning. Programming is aligned by grade bands, and color-coded by PBS KIDS Learning Goals (listed on the back) so that you can easily find the program that's right for your child/student. The links underneath each program provide access to supplemental learning materials related to the program (an internet connection is required to access the links). Grade MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY Bands November 2, 2020 November 3, 2020 November 4, 2020 November 5, 2020 November 6, 2020 Daniel Tiger’s Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood Neighborhood Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood Daniel’s Happy Song/Prince 10:00am The Family Campout/A Game Daniel Makes a Daniel Does Gymnastics/The Play Pretend/Super Daniel! Wednesday’s Happy Night for Everyone Mistake/Baking Mistakes Big Slide Birthday Elinor Wonders Why Elinor Wonders Why Elinor Wonders Why Elinor Wonders Why Elinor Wonders Why 10:30am Make Music Naturally/Light The Tomato Drop/Look What Make Music Naturally/Light -

Ancient Mysteries Revealed on Secrets of the Dead A

NEW FROM AUGUST 2019 2019 NOVA ••• The in-depth story of Apollo 8 premieres Wednesday, December 26. DID YOU KNOW THIS ABOUT WOODSTOCK? ••• Page 6 Turn On (Your TV), Tune In Premieres Saturday, August 17, at 8pm on KQED 9 Ancient Mysteries A Heartwarming Shetland Revealed on New Season of Season Premiere!Secrets of the Dead Call the Midwife AUGUST 1 ON KQEDPAGE 9 XX PAGE X CONTENTS 2 3 4 5 6 22 PERKS + EVENTS NEWS + NOTES RADIO SCHEDULE RADIO SPECIALS TV LISTINGS PASSPORT AND PODCASTS Special events Highlights of What’s airing Your monthly guide What’s new and and member what’s happening when New and what’s going away benefits recommended PERKS + EVENTS Inside PBS and KQED: The Role and Future of Public Media Tuesday, August 13, 6:30 – 7:30pm The Commonwealth Club, San Francisco With much of the traditional local news space shrinking and trust in news at an all-time low, how are PBS and public media affiliates such as KQED adapting to the new media industry and political landscapes they face? PBS CEO and President Paula Kerger joins KQED President and CEO Michael Isip and President Emeritus John Boland to discuss the future of public media PERK amidst great technological, political and environmental upheaval. Use member code SpecialPBS for $10 off at kqed.org/events. What Makes a Classic Country Song? Wednesday, August 21, 7pm SFJAZZ Center, San Francisco Join KQED for a live concert and storytelling event that explores the essence and evolution of country music. KQED Senior Arts Editor Gabe Meline and the band Red Meat break down the musical elements, tall tales and true histories behind some iconic country songs and singers. -

SOTD Hannibal One-Sheet FINAL

Press Contacts: Chelsey Saatkamp, WNET, 212-560-4905, [email protected] Websites: http://www.pbs.org/secrets , http://www.facebook.com/SecretsoftheDead , @secretspbs #SecretsDeadPBS Secrets of the Dead: Hannibal in the Alps Premieres Tuesday, April 10 at 8-9 p.m. on PBS (check local listings) Streams April 11 via pbs.org/secrets and PBS apps Synopsis Hannibal, one of history’s most famous generals, achieved what the Romans thought to be impossible. With a vast army of 30,000 troops, 15,000 horses and 37 war elephants, he crossed the mighty Alps in only 16 days to launch an attack on Rome from the north. For more than 2,000 years, nobody has been able to prove which of the four possible routes Hannibal took across the Alps, and no physical evidence of Hannibal’s army has ever been found…until now. In Secrets of the Dead: Hannibal in the Alps , a team of experts – explorers, archaeologists, and scientists - combine state-of-the-art technology, ancient texts, and a recreation of the route itself to prove conclusively where Hannibal’s army made it across the Alps - and exactly how and where he did it. Notable Talent: Dr. Eve MacDonald, historian and Hannibal expert Dr. Tori Herridge, elephant expert Bill Mahaney, lead scientist and geologist Stephanie Carter, Secrets of the Dead executive producer Noteworthy Facts • The famous crossing of the Alps occurred in 218 BC, a period when Carthage and Rome were competing for world dominance. Hannibal traversed the mountains-- once thought uncrossable--with a force of more than 30,000 soldiers, 15,000 cavalry and most famous of all - 37 elephants. -

Secrets of the Dead Returns Superstorm Sandy: a Live Town Hall

PreMiereS LiVe ThurSday, superstorm sandy: M ay 16 fro M 8 PM - 10PM a live Get an email reminder to watch the show Learn more at thirteen.org MAY 2013 town hall More than six months after Superstorm Sandy ravaged the tri-state region, questions remain regarding the area’s infrastructure and disaster response capabilities and what the future holds. The massive storm — which flooded thousands of homes, cut power to millions of people, and claimed over 100 lives — was the second costliest storm in US history after Hurricane Katrina, with damages estimated between $50 and $60 billion. But beyond the structural damages and subsequent costs, nearly everyone living in New York City, Long Island and New Jersey was affected. Thirteen (New York City), WLIW21 (Long Island), and NJTV (New Jersey), along with other public television stations and local print and radio partners will address community issues and concerns and seek out answers in a multi-platform live two-hour town-hall broadcast with studio audiences at Monmouth University and the Tisch WNET Studios at Lincoln Center on Thursday May 16th, 2013 from 8-10pm. Airing in prime time on Thirteen, WLIW21, and NJTV, Superstorm Sandy: A Live Town Hall will bring together guests and audience questions from New York, New Jersey and Long Island. Hosted by Mike Schneider, Anchor and Managing Editor of NJTV’s nightly news program NJ Today, the special broadcast will delve into key topics regarding the region’s infrastructure and ability to deal with major natural disasters. The broadcast will include in-depth analysis of issues and feature a variety of perspectives to spark a thoughtful conversation about long-term solutions. -

Ancient Mysteries Revealed on Secrets of the Dead A

AUGUSTAPRIL 2019 2020 World War II DID YOU KNOW? PAGE 6 World on Fire: Epic Drama Spans Five Countries at the Start of World War ll PAGE 6 He’s Back! Father Brown:Ancient Mysteries A Heartwarming Season 8Revealed Premiere on New Season of PAGE 11 Secrets of the Dead Call the Midwife PAGE XX PAGE X CONTENTS 2 3 4 5 7 22 PERKS + EVENTS NEWS + NOTES RADIO SCHEDULE RADIO SPECIALS + TV LISTINGS PASSPORT PODCASTS Special events Highlights of What’s airing Your monthly guide What’s new and and member what’s happening when New and what’s going away benefits recommended PERKS + EVENTS Some events may be cancelled or rescheduled due to the evolving Coronavirus (COVID-19) situation. Please check our online listings at kqed.org/events for updates. Taste & Sip 2020 Monday, June 15, at 6:30pm San Francisco Design Center Galleria Join Leslie Sbrocco for this annual affair and sample gourmet food from more than fifty restaurants featured on her show Check, Please! Bay Area. Also, taste local wines and see the stars of the hit tour of Hamilton make a special appearance. kqed.org/events KQED's President and CEO Michael Isip with Leslie Sbrocco KQED.ORG • APRIL 2020 PHOTOS: ALAIN MCLAUGHLIN ALAIN MCLAUGHLIN PHOTOS: 2 Cover: World on Fire photo courtesy of Mammoth Screen NEWS + NOTES KQED’s New Headquarters Takes Shape Demolition and structural steel framing at the site of KQED’s headquarters is substantially complete. Mechanical, electrical and plumbing systems installation is well underway. In the next several months, work on the external and interior walls will commence. -

Kellett Buried with Honors

Call (906) 932-4449 Ironwood, MI Packers victorious Greeen Bay comes away Redsautosales.com 34-24 winners at Dallas SPORTS • 9 DAILY GLOBE Monday, October 7, 2019 Sunny yourdailyglobe.com | High: 56 | Low: 43 | Details, page 2 SOLDIER COMES HOME Kellett buried with honors By TOM LAVENTURE [email protected] IRONWOOD – Walter Kellett is now at eternal rest in the fami- ly plot at Riverside Cemetery in Ironwood. The 12,500-mile journey came 77 years after military historians say Kellett died at the Cabanatu- an Prisoner of War Camp in the Philippines on July 19, 1942. The last mile of his journey was a drizzly cool morning drive in a funeral coach from the McKevitt- Patrick Funeral Home to the cemetery, where people gathered along the route to pay respects. The hearse entered the ceme- tery gate underneath an Ameri- can flag hoisted between two fire trucks with ladders extended. The procession went to the rear of the cemetery where members of the Michigan National Guard Military Funeral Honors Team waited to provide full military honors. The rain did not prevent Dan and Dawne Peterson, of Besse- mer, from waiting with flags to watch the procession go into the cemetery gates. “This is a little bit of bad weather, but that guy went through a hell of a lot more than that,” Dan Peterson said. Tom LaVenture/Daily Globe The technology finally caught A MEMBER of the Michigan National Guard Military Funeral Honors Team presents a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart to Pat Werner, of up to bring these people home, Melrose Park, Ill., at Ironwood’s Riverside Cemetery on Saturday, where her late brother Walter Kellett, was buried 77 years after dying he said. -

Vol 21, Issue 5 / May 2013 Mr

Vol 21, issue 5 / may 2013 When Brooks shot you have13. only We had ten.” the spoof of the infamous shower scene scene infamous shower the of spoof the the other. I was literally crying with hap crying with literally was I other. the the Mel Brooks know we and love—and the Mel Brooks don’t we know at all. the films, the master of comedy turned to the got one thing wrong,” Brooks reveals in l in up of up and outrageously amazing world of Mel Brooks. and and piness,” he tells master of suspense. He shared a rough cutrough a suspense.sharedHeof master name. m of the film with Hitchcock, who declared career, from his early years in live television as a writer for Sid Caesar’s cally avoided a documentary profile being made—until now. of Shows eachman,Carl as Psycho To whet your appetite, we’ve gathered some surprising facts about the life, career, American Masters Mel Brooks: Make a Noise American Masters American The Producers The T Vertigo er f eaturing interviews with Brooks, Matthew Broderick, to his wildly comedic films such as T brilliant. “And then he said you o and other Alfred Hitchcock m as American Masters r Theshowwas The Goes Broadway musical when musical Broadway Brooks saw his first incrediblenumberafter life forever. “It was one man—and it changed his his changed it man—and he was nine years old. Fan ClubFan einer,Joan T —whichmusicaltheTony-winninglaterintoevolved thesameof er High Anxiety film. “Shower rings, starring Ethel Mer Et hel r m ivers,and many others, offersit fascinatinga look at Anything erman , a send- . -

Soundbreaking Starts Monday, November 14 at 10Pm on WOSU TV Details on Page 4 All Programs Are Subject to Change

November 2016 • wosu.org Soundbreaking Starts Monday, November 14 at 10pm on WOSU TV details on page 4 All programs are subject to change. WOSU and NPR Save a Listener’s Life Can public radio save a life? Maybe so. VOLUME 37 • NUMBER 11 Just ask Cynthia Ravitsky of Westerville Airfare (UPS 372670) is published except for June, July One day in September, Cynthia Ravitsky and August by: was driving to Ohio State’s Newark campus WOSU Public Media 2400 Olentangy River Road, Columbus, OH 43210 where she teaches math. She was listening 614.292.9678 to an interview on NPR’s Here and Now on Copyright 2016 by The Ohio State University. All rights 89.7 NPR News with author Gayle Forman reserved. No part of this magazine may be reproduced discussing her new novel Leave Me. The in any form or by any means without express written permission from the publisher. Subscription is by a book tells the story of a working mother minimum contribution of $60 to WOSU Public Media, of twins who is so busy, she doesn’t notice of which $3.25 is allocated to Airfare. Periodicals that she’s having a heart attack postage paid at Columbus, Ohio. Ravitsky was stuck in heavy traffic on State POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Airfare, Route 161 when she started to experience 2400 Olentangy River Road, Columbus, OH 43210 Cynthia Ravitsky a pinching feeling across her chest as she WOSU Public Media listened to the interview. She thought the “OK, I have to make a decision here and I General Manager Tom Rieland discomfort was possibly a muscle spasm, Director of Marketing had time because I was stuck in this traffic. -

Ancient Mysteries Revealed on Secrets of the Dead A

AUGUSTAUGUST 2019 2020 U K YO NO D W I ? D Crime Fighters P A G E 7 He’s Back! Meet the Family Endeavour on of Us: Masterpiece A PBS American Returns Ancient MysteriesPortrait SpecialA Heartwarming for SeasonRevealed 7 on PAGE 9 New Season of PAGE 7 Secrets of the Dead Call the Midwife PAGE XX PAGE X CONTENTS 2 3 4 5 6 7 VIRTUAL EVENTS + NEWS + NOTES RADIO SCHEDULE RADIO SPECIALS + PASSPORT TV HIGHLIGHTS + PERKS PODCASTS LISTINGS Our virtual events What’s happening Your guide to Check out what Watch more with Your guide come to you. at KQED? radio shows. we recommend. KQED Passport. to broadcast television. VIRTUAL EVENTS + PERKS See You Online Although we can’t meet with you in person now, KQED and our partners are offering up lots of fascinating virtual events. Sink into your sofa and enjoy a screening, a listen or watch party and more. For the latest information, please visit kqed.org/events. Dear Homeland Virtual Screening August 12 at 6pm Join us for an upcoming virtual preview screening of the new documentary Dear Homeland featuring Bay Area-based singer- songwriter Diana Gameros. Told in part through her hauntingly beautiful music, the film portrays an artist asserting her voice and fighting to define home for herself as an undocumented immigrant. For more information, visit kqed.org/events. StoryCorps Virtual Tour August 12–September 11 Have a poignant, funny or fascinating personal story to share? During a month-long virtual residency, StoryCorps will join KQED in celebrating the mosaic of Bay Area life by recording personal accounts of the everyday residents who are at its heart. -

Roku Surpasses 700 Channels with New Services from Best Brands in Streaming Entertainment Blockbuster on Demand, FOX NOW, PBS, Spotify, VEVO and Others Join Roku

Roku Surpasses 700 Channels with New Services from Best Brands in Streaming Entertainment Blockbuster On Demand, FOX NOW, PBS, Spotify, VEVO and Others Join Roku LAS VEGAS – Jan. 7, 2013 – With its selection of streaming entertainment growing daily, Roku® Inc. today announced it has surpassed 700 channels on the Roku platform, offering consumers more made- for-TV entertainment than any other streaming device. The company also streamed one billion hours of entertainment in 2012. And with new channels launching this quarter, consumers will have even more entertainment options from the best brands and services in streaming video, music and casual games to choose from – including Amazon Cloud Player, Big Fish, Blockbuster On Demand, FOX NOW, iHeartRadio, PBS, Spotify and VEVO. In other news today, Roku also announced “TWC TV Launching on Roku” and “Roku Adds New Roku Ready Partners for 2013.” “When we launched the first Roku player in 2008, it was the very first device to stream Netflix to the TV and offered just that one channel. Today, the content universe is vastly different with many content producers and owners embracing delivery over the Internet and recognizing the broad appeal and strength of the Roku platform,” said Steve Shannon, general manager of content and services, Roku. “We’re excited to say we have more entertainment choices on Roku today – 700 channels – and more importantly, we have the best brands in streaming entertainment.” New channels on Roku span video, music and casual games including: New Video • Blockbuster On Demand –With thousands of movies and new releases to rent, Blockbuster On Demand boasts a catalog filled with HD titles – including hand-selected movies with the highest ratings from Rotten Tomatoes®. -

Stephanie Carter FINAL

Contact: Lindsey Horvitz, WNET 212-560-6609, [email protected] Press Materials: thirteen.org/pressroom Website: wnet.org Facebook: ThirteenWNET / WLIW21 /NJTV Twitter: @WNET / @ThirteenWNET / @WLIW21 / @NJTVonline Stephanie Carter Named Executive Producer of THIRTEEN’s Secrets of the Dead Series WNET, parent company of New York’s PBS stations THIRTEEN and WLIW21 and operator of NJTV, has announced the promotion of Stephanie Carter to the position of Executive Producer for THIRTEEN’s Secrets of the Dead series, effective July 1, 2017. Carter has worked in a variety of production roles since joining THIRTEEN in 2005, most recently serving as supervising producer on Secrets of the Dead and American Epic. In this position, she will oversee the development, production, promotion, delivery and distribution of the award-winning PBS documentary series that explores iconic historical moments while debunking long-held myths and shining new light on past events and forgotten mysteries. “I’ve worked with Stephanie over the past 10 years, where she has proven to be a talented and indispensable producer on a variety of science and documentary projects for THIRTEEN’s National Programming unit,” said Stephen Segaller, Vice President of Programming for WNET. “She has been an anchor for the Secrets of the Dead series, steadily taking on more editorial and budgetary responsibility for the PBS favorite, making her a natural choice for this position. I’m eager to see what new mysteries we will uncover under Stephanie’s leadership.” Carter’s previous projects -

Patti Smith: Dream of Life” Presents Evocative Portrait of the Legendary Rocker and Artist, Wednesday, Dec

For Immediate Release Contacts: POV Communications: 212-989-7425. Emergency contact: 646-729-4748 Cynthia López, [email protected], Cathy Fisher, [email protected] PBS PressRoom: pressroom.pbs.org/programs/p.o.v. POV online pressroom: www.pbs.org/pov/pressroom “Patti Smith: Dream of Life” Presents Evocative Portrait of the Legendary Rocker and Artist, Wednesday, Dec. 30, 2009, at 9 p.m. in Special Presentation on PBS’ POV Smith was both participant and witness to a seminal scene in American culture; film portrays her friendships and work with Robert Mapplethorpe, William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, Sam Shepard and Bob Dylan “Created over a heroic 11 years … a lovely … first feature. … Mr. Sebring creates a structure for the film in which past and present seem to flow effortlessly and ceaselessly into each other.” — Manohla Dargis, The New York Times Shot over 11 years by acclaimed fashion photographer Steven Sebring, “Patti Smith: Dream of Life” is a remarkable plunge into the life, art, memories and philosophical reflections of the legendary rocker, poet and artist. Sometimes dubbed the “godmother of punk” — a designation justified by clips of her early rage-fueled performances — Smith was much more than that when she broke through with her 1975 debut album, Horses. A poet and visual artist as well as a rocker, she befriended and collaborated with some of the brightest lights of the American counterculture, an often testosterone-driven scene to which she brought a swagger and fierceness all her own. In “Patti Smith: Dream of Life,” the artist’s memories of these times, and of a period of domestic happiness and the tragedies that brought her back to the stage, attain an intense, hypnotic lyricism, much like that of her own songs.