Use of Economic Instruments for Recycling in Lebanon Streg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9685436* Oficiales Del Consejo De Seguridad

Naciones Unidas S/PV.3653 Consejo de Seguridad Provisional Quincuagésimo primer año ª 3653 sesión Lunes 15 de abril de 1996, a las 18.00 horas Nueva York Presidente: Sr. Somavía ...................................... (Chile) Miembros: Alemania ........................................ Sr.Eitel Botswana ....................................... Sr.Nkgowe China .......................................... Sr.QinHuasun Egipto .......................................... Sr.Elaraby Estados Unidos de América ........................... Sra. Albright Federación de Rusia ................................ Sr.Lavrov Francia ......................................... Sr.Dejammet Guinea-Bissau .................................... Sr.Queta Honduras ....................................... Sr.Martínez Blanco Indonesia ........................................ Sr.Wibisono Italia ........................................... Sr.Terzi di Sant’Agata Polonia ......................................... Sr.Włosowicz Reino Unido de Gran Bretaña e Irlanda del Norte ........... Sr.Plumbly República de Corea ................................ Sr.Park Orden del día La situación en el Oriente Medio Carta de fecha 13 de abril de 1996 dirigida al Presidente del Consejo de Seguridad por el Representante Permanente del Líbano ante las Naciones Unidas (S/1996/280) 96-85436 (S) La presente acta contiene la versión literal de los discursos pronunciados en español y de la interpretación de los demás discursos. El texto definitivo será reproducido en los Documentos *9685436* Oficiales -

Layout CAZA Bint Jbeil.Indd

(Tyre) (Sidon) Qada’ Jezzine Qada’ Bint Jbeil Qada’ Sour Qada’ Al-Nabatieh Qada’ Saida Qada’ Hasbaya - Marjeyoun South Lebanon South Beaches Furnished Apartments Bed & Breakfast Handicrafts Restaurants Hotels Natural Attractions Recreation South Lebanon Monuments Table of Contents äÉjƒàëªdG Qada’ Bint Jbeil 1 π«ÑL âæH AÉ°†b Map 2 á£jôîdG Ain Ebel 4-13 πHEG ø«Y Al-Tiri 5-13 …ô«£dG Bint Jbeil 6-13 π«ÑL âæH Bara’achit 7-14 â«°ûYôH Chaqra 8-14 Gô≤°T Deir Intar 9-15 QÉ£fEG ôjO Haris 10-15 ¢üjQÉM Rmeish 11-16 ¢û«eQ Tebnin 12-16 ø«æÑJ Qada’ Hasbaya-Marjeyoun 17 ¿ƒ«©Lôe - É«Ñ°UÉM AÉ°†b Map 18 á£jôîdG Al-Khiam 20-27 ΩÉ«îdG Al-Qlaya’a 21-27 á©«∏≤dG Al-Hibarieh 22-28 ájQÉÑ¡dG Marjeyoun 23-28 ¿ƒ«©Lôe Hasbaya 24-29 É«Ñ°UÉM Deir Mimas 25-29 ¢Sɪ«e ôjO Rachaya Al-Foukhar 26-30 QÉîØdG É«°TGQ Qada’ Jezzine 31 …ô°ûH AÉ°†b Map 32 á£jôîdG AL-A’aichieh 34-49 á«°û«©dG Rihan 35-49 ¿ÉëjQ A’aramta 36-49 ≈àeôY Jernaya 37-50 ÉjÉfôL Safari 38-50 ájQÉØ°U Karkha 39-50 ÉNôc A’nan 40-51 ¿ÉfCG Jezzine 41-51 øjõL Kfar Jarra 42-52 √ôLôØc A’azour 43-52 QhRÉY Mashmousheh 44-53 á°Tƒª°ûe Bkassine 45-53 ø«°SɵH Bteddine Allakish 46-54 ¢û≤∏dG øjóàH Saidoun 47-54 ¿hó«°U Qaytoula 48-54 ádƒà«b Qada’ Al-Nabatieh 55 á«£ÑædG AÉ°†b Map 56 á£jôîdG Arnoun 58-70 ¿ƒfQCG Al-Nabatieh 59-70 á«£ÑædG Jeba’a 60-71 (IhÓëdG ´ÉÑL hCG) ´ÉÑL Jarjoua’a 61-71 ´ƒLôL Houmine Al-Fawqa 62-71 ÉbƒØdG ø«eƒM Deir Al-Zahrani 63-72 »fGôgõdG ôjO Roumine 64-72 ø«ehQ Sarba 65-72 ÉHô°U Arabsalim 66-73 º«dÉ°üHôY Ain Bouswar 67-73 QGƒ°SƒH ø«Y Ain Qana 68-73 ÉfÉb ø«Y Kfarfila 69-74 Ó«aôØc Qada’ Saida 75 Gó«°U AÉ°†b -

Appeal Tel: 41 22 791 6033 Fax: 41 22 791 6506 E-Mail: [email protected]

150 route de Ferney, P.O. Box 2100 1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland Appeal Tel: 41 22 791 6033 Fax: 41 22 791 6506 E-mail: [email protected] Lebanon Coordinating Office LEBANON HUMANITARIAN CRISIS – MELB61 Appeal Target: US$ 6,202,300 Balance Requested from ACT Alliance: US$ 3,992,378 Geneva, 13 September, 2006 Dear Colleagues, On 12 July, Israel launched an offensive against Lebanon following the capture of two of its soldiers by the Lebanese militant group Hezbollah. Israel attacked Hezbollah positions along the border with heavy artillery, tank fire and aerial assaults. For 34 days, the Israeli military operations targeted all regions of Lebanon focusing on the South of Lebanon and the Southern Suburbs of Beirut, a populous, popular and overpopulated area. These regions were already considered in the Lebanese context as very poor. According to the official figures there were 1,287 persons killed, 4,054 injured and 1,200,000 uprooted (25% of the total Lebanese population). 15,000 houses and apartment buildings were completely destroyed and thousands of shops and other constructions severely damaged or destroyed. Basic services such as roads, bridges, energy plants and water were also severely affected. The entire agriculture sector was affected as transport of goods became impossible, export has stopped and most foreign labor escaped because of the shelling. To this should be added the ecological disaster due to the shelling and leakage of around 15,000 tons of fuel oil to the Mediterranean Sea leaving fishermen jobless and without any source of income. On July 27, 2006 an ACT preliminary appeal comprising the ACT/Middle East Council of Churches (MECC) proposal was issued to respond to this emergency. -

D D D L'8:L D

Submission Form To The Lebanon Recovery Fund Steering Committee To be completed by the UN Resident Coordinator's Office (RCO) Meeting No: Date of Meeting: Item No: Programme/project: (To be completed by the Participating UN Organisation and endorsed by SC) To: Lebanon Recovery Fund Steering Date of Submission: 29 November 2011 Committee From: Lebanese Family Planning Contact: Toufic Osseiran, Honorary President, Association I UN Women Rania Tarazi, Assistant Regional Program Director Through: Project Advisory Group (PAG) Contact: Toufic Osseiran, tel 961 1 311978, email: [email protected] D Endorsement Rania Tarazi, tel. +962 6 5200060 ext. 1008, email: D Comments [email protected] Proposed submission, if approved would Proposed submission resulted from: result in: D National Authorities initiative within national D Continuation of existing priorities programme/project D UN Agency initiative within national priorities l'8:l New programme/project l'8:] Other (explain): Joint initiative between LFPA D Other (explain) and UN Women within national priorities Project title: Local Development through Women Empowerment- in Nabatieh Villages Amount of funds requested for proposed programme/project: $ 698,340 Estimated number of beneficiaries: direct 6,604 indirect approximately 90,000 people and 35 organizations Percentage and amount of indirect costs requested: 7% Background The project was jointly developed by UN Women and the Lebanese Family Planning Association (LFPA). UN Women, an non-resident agency in Lebanon, conducted a gender needs assessment in April 2011 to identify entry points for its technical support to national organizations within its mandate of gender equality. In addition to identifying potential partners, the gender needs assessment has shown that women have not been systematically included in the recovery and reconstruction efforts in Lebanon. -

Guidelines for Amendments to the List of Reserved and Prohibited Domain Names Under the LBDR (Published: 15 November 2017 - Updated: 14 December 2018)

Guidelines for amendments to the list of Reserved and prohibited domain names under the LBDR (Published: 15 November 2017 - Updated: 14 December 2018) This memorandum specifies the guidelines for amendments to Appendix-A. Adding new names Whether new names should be reserved, or their registration should be prohibited, is subject to ongoing assessment. These might be new generic domains, for example, if a new category of enterprise should emerge along the lines of AS (a limited-liability company); new geographical names, for example if new municipalities are created; new technical names in connection with the establishment of new services; and so on. If names which may be relevant emerge, an assessment is undertaken in consultation with the LBDR Advisory Board of whether these names fulfil the requirements for inclusion in one of the categories in Appendix A. LBDR may temporarily prohibit the names until a decision has been made. Notice of the decision that the names are to be added to Appendix A is given in the normal way, although for practical reasons the names will also be blocked during the notice period. The addition of new names to the prohibited/reserved list will not have retroactive effect. This means that names that have already been registered will not be removed even if they are added to the list. If the name is deleted later, new registration of the name will however be blocked. Such names cannot be transferred to a new domain name holder either. Taking names into use or removing names Names that are prohibited Every year, LBDR carries out an assessment of whether these names should still be prohibited or should be removed from Appendix A. -

Collaboration with Municipalities

Name of Implementing Governorat Qadaa Cadaster Partner e North Batroun Batroun North Batroun Helta North Batroun Assia Noth Batroun Chebtine North Batroun Mehmarch North Batroun Zein North Batroun Jran North Batroun Douma North Batroun Kfaraabida North Batroun Bejdarfel North Batroun Aabrine North Batroun Bchaale North Batroun Dael North Koura Amioun North Koura Bkeftine North Koura Kfarhazir North Koura Kfaraaka North Koura Btouratij North Koura Nakhle North Koura Batroumin Al Midan North Koura Bterram North Koura Barsa North Zgharta Zgharta‐ Ehden North Zgharta Rachaiine North Zgharta Kfarzaina North Zgharta Ayrounieh Noth Tripoli Mina Al Hadadine‐ Al Tal, Noth Tripoli Tebenneh, and Daher Al Mogher North Bcharre Hasroun North Bcharre Qnat North Bcharre Beit‐ Mender North Bcharre Aabdine North Bcharre Hadath Al Jebbeh North Bcharre Barhalion North Bcharre Bakaa Kafra Mount Lebanon Chouf Bekaata Mount Lebanon Chouf Joun Mount Lebanon Chouf Sibline Mount Lebanon Chouf Barja Mount Lebanon Chouf Nehme Mount Lebanon Chouf Chhim Mount Lebanon Chouf Jiyeh Mount Lebanon Chouf Rmeileh Mount Lebanon Chouf Ketermaya Mount Lebanon Chouf Wardanieh Mount Lebanon Chouf Jadra Mount Lebanon Chouf Debbieh Mount Lebanon Chouf Mreste Bekaa Zahle Anjar Bekaa West Bekaa Al Manara Bekaa Zahle Jdita Bekaa Zahle Mryjat Bekaa West Bekaa Sohmor Bekaa West Bekaa Tal Znob Bekaa West Bekaa Ghazzeh Bekaa West Bekaa Al Sultan Yakoub Bekaa West Bekaa Sawerieh Bekaa Zahle Majdal Anjar Bekaa Zahle Saadnayel Bekaa Zahle Qabelias Bekaa Zahle Zahle Bekaa Zahle Ali el Nahri -

Nota De Actualidad 3/2018

NOTA DE ACTUALIDAD 3/2018 8 de mazo de 2018 * Dra. Raniah Tourkmani bibliotecasgc.bage.es Nota de actualidad Persigue dar una idea de lo que se habla y escribe en el mundo árabe, de sus preocupaciones y visión de diversos temas de actualidad. Al-Zawahiri, envía un nuevo mensaje a los musulmanes del Magreb occidental El líder de al-Qaeda, Ayman al-Zawahiri, ha aparecido en una nueva grabación de vídeo en el que llama a los musulmanes del Magreb occidental a matar a los soldados franceses en la región del Sahel africano. El vídeo ha sido publicado por el grupo americano “Site”, que se encarga de vigilar las páginas web de terrorismo y las organizaciones armadas. En el vídeo, titulado “Descendientes de los negros, Francia ha regresado”, aparece el líder de la organización hablando durante siete minutos: “aquellos que combatieron vuestros padres y los mataron y los expulsaron, han regresado para matar a vuestros hermanos musulmanes y recordaros que aún estáis bajo su ocupación”. En relación a las revueltas de la primavera árabe Foto: Euronews arabic ha señalado “la antigua corrupción ha vuelto mucho más feroz“ El vídeo no muestra la fecha de grabación y no hace referencia en su discurso a los últimos ataques en Uagadugú, que fueron reivindicados por el grupo Nusrat al-Islam wa-l-Muslimin (Grupo Apoyo al Islam y Los Musulmanes), grupo vinculado a al-Qaeda y que actúa en Mali. Sin embargo aún no se ha podido determinar la veracidad del vídeo ni su grabación en los días posteriores al ataque contra la Embajada francesa y la sede Estado Mayor del ejército de Burkina Faso en Uagadugú. -

Lebanon National Operations Room Daily Report on COVID-19

Lebanon National Operations Room Daily Report on COVID-19 Tuesday, October 13, 2020 Report #209 Time Published: 10:30 PM New in the report: - Decision issued by the Ministry of Interior and Towns No. 1252 on 10/13/2020 regarding amending the schedule of villages and towns that have been closed due to the high number of Coronavirus Cases. Number of Cases by Location • 9,788 case is Under investigation Beirut 99 Kesrwen 42 Zahleh 82 Matn 98 Ein Al Mreisseh 1 Sarba 1 Al Maydan 3 Borj Hammoud 4 Ras Beirut 1 Kaslik 1 Barbara 2 Sin El Hil 7 Manara 1 Zouk Michael 4 Maallaqa 6 Jdeidet Metn 4 Raouche 2 Ghadir 3 Mar Antonios 1 Bouchrieh 5 Hamra 7 Zouk Mosbeh 6 Hoch Al Oumara 4 Dora 5 Mseitbeh 4 Adonis 3 Arady 4 SedBaouchrieh 2 Mar Elias 3 Haret Sakher 2 Mar Elias 1 Sabtieh 1 Tallet Al Khayyat 3 sahel Alma 2 Forzol 2 Dekwene 16 Sanayeh 1 Bouar 1 Hazzarta 1 Antelias 6 Zarif 1 Okaybeh 1 Ablah 3 Jal Al Dib 4 Mazraa 6 Ajaltoun 1 Qaa Al Rim 1 Naqqash 10 Borj Abi Haidar 8 Ballouneh 4 Ksara 5 Zalka 5 Basta Fawka 3 Jeita 1 Wady Al Arayesh 1 Byaqout 1 Malaab Al Baladi 1 Ghazir 2 Makseh 1 Deir Aoukar 1 Tariq Jdeedeh 21 Kfarhbab 1 Taalabaya 6 Mansouriyeh 12 Ras Al Nabaa 4 Maarab 1 Jdita 2 Dayshounieh 1 Basta Tahta 2 Dar'oun 1 Taanayel 1 Fanar 3 Ashrafieh 11 M'ayssra 1 Saadnayel 4 Ein Saadeh 1 Others 19 Reifoun 3 Qab Elias 5 Roumieh 3 Baabda 239 Hrajel 2 Mreijat 2 Bsalim 8 Chiah 20 Others 1 Hoch Qayssar 1 Rabwe 1 Jnah 2 Byblos 14 Bar Elias 5 Deek El Mahdy 1 Ouzai 4 Byblos 7 Anjar 1 Bekfayya 1 Bir Hassan 5 Mastita 2 Majdel Anjar 1 Broummana 2 Cite Sportif 1 -

Law 360 Encouraging Investments in Lebanon

English Translation Draft Law 360 Encouraging Investments in Lebanon The Parliament has passed, And the President of the Republic publishes the following law: Article 1: In order to apply the articles of this law, the following explanations are given: 1- The institution: The public institution created by this law in order to encourage investments in Lebanon. 2- The board of administration: The board of administration of the institution created by this law. 3- Head of the institution: Head of the institution, chairman of the board and general manager of the institution created by this law. 4- The project: The investment project related to any sectors falling under this law. 5- The investor: The real or moral Lebanese, Arab or foreign person who invests in Lebanon in accordance with this law. Article 2: This law applies to all investments belonging to investors, who wish to benefit from its articles in the fields of industry, agriculture and agricultural industry, tourism, information technology, and other sectors that the council of ministers shall define by decree. Article 3: A public institution called “The Public Institution for Encouraging Investments in Lebanon” is created. It enjoys moral entity and financial and administrative independence, and is attached to the Prime Minister who exercises the tutorial authority over it. It complies with the articles of this law. Article 4: The administration of the Institution is done by a board of administration composed of seven members appointed for four years by a decree of the council of ministers. The member should be: 1- Lebanese for more than ten years. -

Details of In- Dividual Work Packages Or Studies That Are Expected to Be Launched by CDR During the Year 2015 and After

Please note that this report is also available on the internet at CDR’s home page: www.cdr.gov.lb Message from the President 2 Introduction 3 General Overview of the sectors 4 Physical Infrastrucure Electricity 10 Post and Telecommunications 18 Transportation 20 Social Infrastructure Education 34 Public Health 48 Social and Economic development 54 Land Use and Environment 68 Basic services Potable Water supply 82 Waste water 98 Solid waste 108 Productive sectors and other sectors Agriculture and Irrigation 112 Sovereign Services 122 Financing the reconstruction program 126 2 Message from the President CDR OCTOBER 2015 MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT In 2014, the Lebanese Government and the Lebanese public institutions combined their efforts to improve the level of public services and to with- stand the repercussions of the Syrian crisis which placed huge strains on the economic and social activity and increasingly overburdened the in- frastructure and public services. The Lebanese Government called upon the international community to scale up its support to help the Lebanese public entities in assuming their responsibilities which greatly outweighed humanitarian and rescue interventions and entailed significant develop- ment challenges. The Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR) and the Ministry of Social Affairs endeavored to seek funding to finance development pro- grams and projects, as well as to integrate sectorial programs into plans and strategies aimed at addressing the negative impacts of the Syrian Cri- sis on Lebanon. On the other hand, the CDR continued to implement the previously sched- uled programs and to prepare for future projects. In 2014, new contracts were awarded across all sectors with emphasis on the water and wastewa- ter sectors. -

Occupancy Rate of COVID-19 Beds and Availability

[Type here] Lebanon National Operations Room Daily Report on COVID-19 Tuesday.23 March.2021 Report #369 Time Published: 10:00 PM Occupancy rate of COVID-19 Beds and Availability For daily information on all the details of the bed’s distribution availability for Covid-19 patients among all governorates and according to hospitals, kindly check the dashboard link: Computer: https:/bit.ly/DRM-HospitalsOccupancy-PCPhone:https:/bit.ly/DRM-HospitalsOccupancy-Mobile Ref: Ministry of public health Distribution by Villages Beirut 256 Baabda 583 Maten 270 Chouf 210 Kesrwen 58 Akkar 122 Ain Mraisseh 2 Chiyah 31 Borj Hammoud 27 Damour 2 Jounieh Sarba 3 Halba 2 Aub 2 Jnah 12 Nabaa 3 Saadiyat 3 Jounieh Kaslik 2 Chekh Mohamad 2 Ras Beyrouth 7 Ouzaai 17 Sinn Fil 11 Naameh 3 Zouk Mkayel 2 Daoura 1 Manara 1 Bir Hassan 16 Horch Tabet 1 Mechref 1 Haret Meir 1 Minyara 2 Raoucheh 3 Madinh Riyadiyeh 1 Jisr Bacha 1 Chhim 18 Jounieh Ghadir 2 Machha 2 Hamra 12 Ghbayreh 21 Jdaidet Matn 10 Mazboud 6 Zouk Mosbeh 2 Aarqa 2 Ain Tineh 2 Ain Roummaneh 19 Baouchriyeh 2 Dalhoun 1 Haret Sakhr 1 Souaisset Aakkar 1 Msaitbeh 9 Furn Chebbak 7 Daoura 2 Daraiya 2 Sahel Aalma 3 Borj Arab 1 Ouata Msaitbeh 1 Haret Hreik 94 Raoda Baouchriyeh 7 Ketermaya 14 Tabarja 1 Jobrail 1 Mar Elias 11 Laylakeh 35 Sadd Baouchriyeh 2 Aanout 3 Adma Oua Dafneh 1 Tikrit 1 Dar Fatwa 2 Borj Brajneh 109 Sabtiyeh 8 Sibline 4 Safra 3 Beit Mellat 1 Sanayeh 1 Mreijeh 25 Dekouaneh 35 Bourjein 2 Bouar 3 Borj 1 Zarif 6 Raml Aali 2 Mkalles 1 Barja 27 Aaqaybeh 2 Bezbina 3 Qantari 1 Tahouitat Ghadir 23 Antelias -

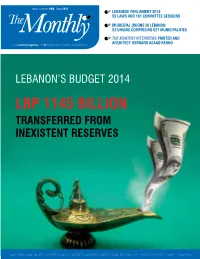

Lbp 1145 Billion Transferred from Inexistent Reserves

issue number 155 |June 2015 LEBANESE PARLIAMENT 2014: 55 LAWS AND 161 COMMITTEE SESSIONS MUNICIPAL UNIONS IN LEBANON: 53 UNIONS COMPRISING 627 MUNICIPALITIES THE MONTHLY INTERVIEWS PAINTER AND ARCHITECT: BERNARD ASAAD RENNO www.monthlymagazine.com Published by Information International sal LEBANON’S BUDGET 2014 LBP 1145 BILLION TRANSFERRED FROM INEXISTENT RESERVES Lebanon 5,000LL | Saudi Arabia 15SR | UAE 15DHR | Jordan 2JD| Syria 75SYP | Iraq 3,500IQD | Kuwait 1.5KD | Qatar 15QR | Bahrain 2BD | Oman 2OR | Yemen 15YRI | Egypt 10EP | Europe 5Euros June INDEX 2015 4 LEBANON’S BUDGET 2014: LBP 1145 BILLION TRANSFERRED FROM INEXISTENT RESERVES 18 LEBANESE PARLIAMENT 2014: 55 LAWS AND 161 COMMITTEE SESSIONS 19 MUNICIPAL UNIONS IN LEBANON: 53 UNIONS COMPRISING 627 MUNICIPALITIES 25 USD 9 MILLION FOR THE STATE SHURA COUNCIL BUILDING 26 NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF PAKISTAN QUOTA FOR WOMEN AND MINORITIES 28 NAJIB ALAMUDDINE (1909-1996) P: 31 P: 46 30 DEFENDING SUSTAINABLE WOMEN’S RIGHTS: A PATH FOR PEACE? SAID CHAAYA 31 INTERVIEW: PLASTIC ARTIST AND ARCHITECT BERNARD ASAAD RENNO 33 CHF LEBANON DEVELOPMENT AND HUMANITARIAN RELIEF 35 POPULAR CULTURE 36 DEBUNKING MYTH#92: DO CARROTS IMPROVE YOUR EYESIGHT? 37 MUST-READ BOOKS: TOMORROW, WE WILL ENTER THE CITY IBRAHIM SALAMEH P: 31 38 MUST-READ CHILDREN’S BOOK: FACE TO FACE WITH TORNADOS 39 LEBANON FAMILIES: NAHLE FAMILIES 40 DISCOVER LEBANON: NAHLE 48 ISLAMIC ORGANIZATIONS (5) TAHRIR PARTY (LIBERATION PARTY) 41 DISCOVER THE WORLD: DOMINICA AN ISLAMIC OR A LEBANESE STATE? 42 APRIL 2015 HIGHLIGHTS 49 REAL