Supplement 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STATE of NEW HAMPSHIRE Dept

STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE Dept. of Administrative Services Div. of Procurement and Support Services Bureau of Purchase and Property State House Annex Concord, New Hampshire 03301 Date: May 30, 2018 NOTICE OF CONTRACT - REVISION (To update SimplexGrinnell Contact) COMMODITY: Fire Suppression System Testing & Inspection Services CONTRACT NO.: 8002273 NIGP: 936-3376 CONTRACTOR: SimplexGrinnell LP VENDOR # : 175878 35 Progress Ave. Nashua, NH 03062 CONTACT PERSON(s): Danielle Antonellis Tel. No.: (978) 353-3588 E-Mail: [email protected] (Additional contacts listed on page for 24-hour emergencies, scheduling, etc.) EFFECTIVE FROM: March 1, 2018 Through: December 31, 2018 QUESTIONS: Direct any questions to Heather Kelley, 603-271-3147 or [email protected] SimplexGrinnell Elevator 24-Hour Emergency Service 1-603-886-1100 To report a problem: Select Option 1, then Option 3 for the Operator Testing/Inspection Coordinator Service Work Coordinator (Inspection Scheduler) (Service Scheduler) Derek Mellino Kerri Perkins (603) 521-1113 (603) 521-1121 [email protected] [email protected] Sprinkler Sales Rep Deficiency Sales Rep Jimy Weaver Craig LaPointe (603) 897-9622 (603) 521-1147 [email protected] [email protected] PMA Rep Inspection/Service Manager Jessica Chames Michelle Van Valkenberg (603) 320-2739 (603) 219-2654 (cell) (603) 521-1155 (office) [email protected] [email protected] Total Service Manager Dean Bedard (603) 921-8256 (cell) (603) 521-1132 (office) [email protected] SCOPE OF WORK: The purpose of this contract is to provide all labor, tools, transportation, materials, equipment and permits as necessary to provide the required level of services as described herein. -

Dramatic Loft, Main Level Master Bedroom with Walk in Closet. Large Family Room, Dining Room and Flowing Kitchen with Pantry. Tw

The Piedmont Triad’s Premier Builder Aspen Dramatic loft, main level master bedroom with walk in closet. Large family room, dining room and flowing kitchen with pantry. Two story family room open to second floor. Bonus room/bedroom over the garage. Bedrooms: 3 Full Baths: 2 Half Baths: 1 Square Footage: 2.220 Stories: 2 Housing Opportunity. Prices floor plans & standard features are subject to change without notice. The elevations, floor plans & square footages shown are for illustrative purposes only. Structural or other modifications which are in accordance with applicable building codes may be made as deemed necessary or appropriate given the elevation to other characteristics of the lot on which the home is constructed. The dimensions and total square footage shown are approximations only. Actual dimensions and total square footage of the home constructed may vary. WWW.GOKEYstoNE.COM | The Piedmont Triad’s Premier Builder Optional Sunroom OPTIONAL BAY WINDOW Loft Bedroom Breakfast Master (Optional Kitchen Bedroom 4) 2 Nook Suite OPTIONAL Optional F Sunroom OPTIONAL BAY WINDOW SEPARATE SHOWER OPTIONAL FIREPLACE 60" VANITY W D W Open to OPTIONA TRANSO WINDOW Family PICTURE Below Room Loft Bedroom M Breakfast Master L (Optional Kitchen Bedroom 4) 2 Suite 42" GARDEN Nook TUB OPTIONAL F Luxury Master Bath Option SEPARATE SHOWER OPTIONAL Optional FIREPLACE 60" VANITY W Sunroom OPTIONAL BAY WINDOW D 2 CaW r Open to OPTIONA TRANSO WINDOW Family PICTURE Bedroom Below Room Garage 3 M L 42" GARDEN TUB Luxury Master Loft Bedroom Breakfast Master Bath Option (Optional Kitchen Bedroom 4) 2 Nook Suite OPTIONAL F First Floor Plan Second Floor Plan 2 Car Bedroom Garage SEPARATE 3 SHOWER OPTIONAL FIREPLACE 60" VANITY W D W Open to OPTIONA TRANSO WINDOW Family PICTURE Below Room M L First Floor Plan 42" GARDEN Second Floor Plan TUB Luxury Master Bath Option 2 Car Bedroom Garage 3 Aspen First Floor Plan Second Floor Plan WWW.GOKEYstoNE.COM | . -

Fire Service Features of Buildings and Fire Protection Systems

Fire Service Features of Buildings and Fire Protection Systems OSHA 3256-09R 2015 Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 “To assure safe and healthful working conditions for working men and women; by authorizing enforcement of the standards developed under the Act; by assisting and encouraging the States in their efforts to assure safe and healthful working conditions; by providing for research, information, education, and training in the field of occupational safety and health.” This publication provides a general overview of a particular standards- related topic. This publication does not alter or determine compliance responsibilities which are set forth in OSHA standards and the Occupational Safety and Health Act. Moreover, because interpretations and enforcement policy may change over time, for additional guidance on OSHA compliance requirements the reader should consult current administrative interpretations and decisions by the Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission and the courts. Material contained in this publication is in the public domain and may be reproduced, fully or partially, without permission. Source credit is requested but not required. This information will be made available to sensory-impaired individuals upon request. Voice phone: (202) 693-1999; teletypewriter (TTY) number: 1-877-889-5627. This guidance document is not a standard or regulation, and it creates no new legal obligations. It contains recommendations as well as descriptions of mandatory safety and health standards. The recommendations are advisory in nature, informational in content, and are intended to assist employers in providing a safe and healthful workplace. The Occupational Safety and Health Act requires employers to comply with safety and health standards and regulations promulgated by OSHA or by a state with an OSHA-approved state plan. -

Distinguishing Standard Features

DISTINGUISHING STANDARD FEATURES ELEGANT EXTERIORS ARE EASY TO MAINTAIN OLD WORLD MOLDING & MILLWORK THE PERSONAL TOUCH Ultra- Exclusive 10 acre Gated Enclave Situated in X-Large 6 ¾” 1 Piece Crown Molding in Foyer, Floor Plans Offer Plenty of Flexibility to a Beautiful Country Setting in Close Proximity to Dining Room and Formal Powder Room. Personalize the Home with Custom Designs and Shopping Hubs, Cultural Areas and Events, Fine 7 ¼” Baseboards, 3 ¼”Casing for Windows and Finishes Dining, and More Doors Buyers may Further Customize the Home by Award-Winning and Nationally Recognized West Continental Style, 2 panel Solid Core Interior Choosing from a Vast Array of Styles and Chester Area School District – Rustin High School Doors with Aged Bronze Hardware throughout the Finishes for all Cabinetry and Countertops Quick and Easy Access to All Major Home Extensive Collection of Species Hardwood Thoroughfares Coffered Ceiling with 1 Piece Crown Molding Flooring, Ceramic Tile Styles and Unique Prestigious Homes in a Private Setting with Large Hardware to Complement the Buyer’s Specific Home sites Design Ideas Stone and James Hardie HardiePlank® Lap SOPHISTICATED BATHS Siding SAFETY FIRST FOR EVERY FAMILY Historic Stone Entrance Walls Century Cabinetry Flagstone Front Porch with Brick Paver Granite Countertop in Master Bath Hardwired Smoke Detectors with Battery Backup Walkways and Lush Landscaping Frameless Shower Door in Master Bath Smoke/Carbon Monoxide Detectors on each Public Water 6’ Soaking Tub in Master Bath Floor Kohler 24” Memoirs Pedestal Sink in Powder Tankless Hot Water Heater EXQUISITE INTERIORS Room Interior/Exterior Basement Drain System Five Bedrooms, Three Full Baths and a Powder ENERGY EFFICIENT CONSTRUCTION QUALITY CONSTRUCTION Room in Most Models Walk out Finished Basement (1200 +/- sq. -

Home & Gite Plus Pool

16, Avenue de la Marne - 65000 TARBES Tel.: 0033 (0) 562.345.454 . - Fax : 0033 (0) 562.346.660 abafim.com You can contact us by email using [email protected] Home & Gite Plus Pool 325 000 € [ Fees paid by the seller ] ● Reference : AF24620 ● Number of rooms : 11 ● Number of bedrooms : 8 ● Living space : 342 m² ● Land size : 1 400 m² ● Local taxes : 1 130 € Located in the tranquil countryside close to the town of Maubourguet is this beautiful property for sale which dates from the end of the 19th century. Without any overlooking neighbours and with a swimming pool, it has a total of 342m² of living space (170m² for the main house and 172m² for the gite) including eight bedrooms, four of which are in the attached gite, two kitchens, two sitting rooms, a bathroom, two washrooms, a cinema room, a conservatory, a "summer" kitchen and a workshop and all on 1400m² of leafy and flower-filled gardens. Perfect for a primary home with a rental opportunity, gite, chambre d'hotes or a large family, its spacious layout will suit many projects. Main House A central and south-facing entrance opens to a hall serving, to the left, a 33m² living room with two-sided wood burner (to the sitting room and conservatory) and to the right a 15m² laundry room. The 21m² north-facing conservatory is accessed from the sitting room. Further on to the left is the 16m² fitted kitchen and stairs leading up. A washroom and toilet complete this level. Tiled flooring throughout. Upstairs is a landing serving four bedrooms (13, 20, 21 & 24m²) and bathroom with toilet. -

Floor Plan 3 to 4 Bedrooms | 2 2 to 3 2 Baths | 2- to 3-Car Garage

1 1 THE GRANDVILLE | Floor Plan 3 to 4 Bedrooms | 2 2 to 3 2 Baths | 2- to 3-Car Garage OPT. OPTIONAL OPTIONAL OPTIONAL WALK-IN EXT. ADDITIONAL COVERED LANAI EXPANDED FAMILY ROOM EXTERIOR BALCONY CLOSET PRIVACY WALL AT OPTIONAL ADDITIONAL EXPANDED COVERED LANAI BEDROOM 12'8"X12'6" COVERED VAULTED CLG. OPT. LANAI FIREPLACE FAMILY ROOM BONUS ROOM BATH VAULTED 21'6"X16' 18'2"X16'1" CLG. 9' TO 10' SITTING 10' TO 13'1" VAULTED CLG. VAULTED CLG. OPTIONAL AREA COVERED LANAI A/C DOUBLE DOORS A/C 10' CLG. BREAKFAST 10' CLG. AREA 9'X8' MECH. MECH. 10' CLG. OPT. SLIDING OPT. GLASS DOOR LOFT WINDOW 18'2"X13' 9' TO 10' BATH VAULTED CLG. MASTER 9' CLG. 9' CLG. BEDROOM CLOSET 22'X13'4" 10' CLG. LIVING ROOM BEDROOM 2 DW OPT. 10' TO 10'8" 14'X12' 11'8"X11'2" 10' CLG. COFFERED CLG. 10' CLG. DN OPT. 10' TO 10'8" GOURMET KITCHEN DN COFFERED CLG. NOTE: NOTE: OPT. 14'4"X13' MICRO/ THIS OPTION FEATURES AN ADDITIONAL 483 SQ. THIS OPTION FEATURES AN ADDITIONAL 560 SQ. WINDOW 10' CLG. WALL FT. OF AIR CONDITIONED LIVING AREA. FT. OF AIR CONDITIONED LIVING AREA. OVEN REF. NOTE: NOTE: PANTRY SPACE OPTION 003 INTERIOR WET BAR, 008 DRY BAR, 021 CLOSET OPTION 003 INTERIOR WET BAR, 008 DRY BAR, 032 ADDITIONAL BEDROOM WITH BATH, 806 BONUS ROOM, 806 ALTERNATE KITCHEN LAYOUT, ALTERNATE KITCHEN LAYOUT, AND 812 BUTLER AND 812 BUTLER PANTRY CANNOT BE 10' CLG. 10' CLG. PANTRY CANNOT BE PURCHASED IN PURCHASED IN CONJUNCTION WITH THIS OPTION. -

Active Fire Protection Systems

NIST NCSTAR 1-4 Federal Building and Fire Safety Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster Active Fire Protection Systems David D. Evans Richard D. Peacock Erica D. Kuligowski W. Stuart Dols William L. Grosshandler NIST NCSTAR 1-4 Federal Building and Fire Safety Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster Active Fire Protection Systems David D. Evans Society of Fire Protection Engineers Richard D. Peacock Erica D. Kuligowski W. Stuart Dols William L. Grosshandler Building and Fire Research Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology September 2005 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlos M. Gutierrez, Secretary Technology Administration Michelle O’Neill, Acting Under Secretary for Technology National Institute of Standards and Technology William Jeffrey, Director Disclaimer No. 1 Certain commercial entities, equipment, products, or materials are identified in this document in order to describe a procedure or concept adequately or to trace the history of the procedures and practices used. Such identification is not intended to imply recommendation, endorsement, or implication that the entities, products, materials, or equipment are necessarily the best available for the purpose. Nor does such identification imply a finding of fault or negligence by the National Institute of Standards and Technology. Disclaimer No. 2 The policy of NIST is to use the International System of Units (metric units) in all publications. In this document, however, units are presented in metric units or the inch-pound system, whichever is prevalent in the discipline. Disclaimer No. 3 Pursuant to section 7 of the National Construction Safety Team Act, the NIST Director has determined that certain evidence received by NIST in the course of this Investigation is “voluntarily provided safety-related information” that is “not directly related to the building failure being investigated” and that “disclosure of that information would inhibit the voluntary provision of that type of information” (15 USC 7306c). -

Season 1, Ep 1036: Family Heirloom Home

SEASON 1, EP 1036: FAMILY HEIRLOOM HOME Nicole’s grandfather built their home in the 1950’s and it’s been passed down in her family from generation to generation. The home is rich with family history and Nicole and her husband Graeme are thrilled to be able to raise their three kids in the home she grew up in. But a house that used to work for three people is no longer functioning for their family of five. The windows in the kitchen leak in the winter and create dead space, the uneven hardwood and concrete floors cause tripping hazards and the dining room layout feels cramped. Drew and Jonathan rework the kitchen, dining room, living room and converted family room into a bright, fresh, modern family home that perfectly blends the old with the new. 1 2 4 7 1 5 3 6 8 10 7 11 9 1. BLANCO – Kitchen Sink & Faucet 7. TiILEMASTER – Kitchen Backsplash 2. CASA BELLA WINDOWS & DOORS – Kitchen Window 8. HALO – Pot Lights 3. TILESMASTER – Shower Tile 9. CRAFT ARTISAN WOOD FLOORS – Hardwood Floors 4. VALLEY ACRYLIC – Shower Fixtures 10. LIGHTS CANADA – Pendant Light 5. ADANAC GLASS – Shower Enclosure 11. ARIA VENTS – Floor Vents 6. EMTEK – Cabinet Hardware RESOURCE GUIDE SEASON 1, EP 1036: FAMILY HEIRLOOM HOME ROOM ITEM COMPANY PRODUCT NAME PRODUCT CODE Main Floor Pot Lights HALO HLB4LED HLB4 LED Main Floor Vents Aria Vent Aria Lite N/A Main Floor Hardwood Flooring CRAFT Artisan Wood Floors Stylewood N/A Front Entry Hardware Emtek Adelaide Entry Set 3312 Kitchen Faucet Blanco Catris 401918 Kitchen Sink Blanco Quatrus U 2 401247 Kitchen Accessory Blanco -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX A Archives room 238 Area of additional building regulations (airport) 417 Abbreviations 1 Area pay desk (retail) 257 Absorption area 482, 483 Area surveillance 119 Access 139, 146 Armchair 11 Access control system 17, 119 Armoured glass 107 Access principles 139 Aron Hakodesh 288 Accessible building 21 ff. Art library 250 Accessible housing 23 Art teaching 192 Accessible lift 134 Artifi cial ice rink 344 Accessible parking place 21, 22, 23 Assisted fl at for the elderly 168 Accident and emergency 291, 299 Asymmetrical bars (gym) 365 Acoustic refl ector 221 At-grade crossing 381 Acoustics 220, 221, 223 Athletics 326 Additional technical contract conditions 61 Atrium house 143 Administration 231 Audience row (theatre) 212 Advertising displays 502 Audience seating 212 Aeroplane category 423 Auditorium 198, 200, 211, 212, 222, 219, 222, 223 Air conditioning 242 Auditorium width 211 Air conditioning plant room 531 Autobahn 378 Air conditioning system 531 Aviation Law 371, 418 Air curtain 115 Aviation Noise Law 418 Air freight 418 Award procedure (contract) 61 Air gap 90 Awning 500 Air handling equipment 531 Azimuth 488, 490 Air humidity 37 Air recirculation system 530 Air terminal 485 B Air-water systems 530 Airborne sound 478 Baby grand piano 11 Airborne sound insulation 477, 478 Baby ward 308 Airport 419 Backing-up (drainage) 527 Airport regulations 418 Back-ventilation 473 Airside 421 Background ventilation 529 Aisle, theatre 212 Badminton 322, 356 Akebia 434 Bakery 278 Alignment (photovoltaics) 467 Baking table 190 All-purpose room -

Town of Belmont Department of Public Works Space Needs Summary

Town of Belmont Department of Public Works Space Needs Summary Name of Space General Description of Needs DPW Director Office Desk work area, support furnishings, seating for up to 2 visitors, and small meeting area. Assistant DPW Director Desk work area, support furnishings, seating for up to 2 Office/Hwy Division Director visitors, and small meeting area. Highway Operations Manager Desk work area, support furnishings, seating for up to 2 visitors, and small work table area. Parks & Cemetery Division Future office area to include desk work area, support Director Office furnishings, seating for up to 2 visitors, and small work table area. Water Superintendent Desk work area, support furnishings, seating for up to 2 visitors, and small work table area. Assistant Water Superintendent Desk work area, support furnishings, seating for up to 2 visitors, and small work table. Reception Area / Vestibule / Air lock, seating area, counter area Waiting Area DPW Administration Office Work area for seven (7) Administrative Assistants, including Area a work area/active file area Cemetery Sales Office Secluded office with table and seating Administration Toilet Facilities Locate adjacent to conference room, single fixture, ADA compliant Cemetery Records Storage Room Fire proof records storage Copy / File / Mail Area Counter area with room for water / sewer billing equipment, copy machine, layout table CAD / GIS Area CAD/GIS work stations with space for large scale plotter Active File Storage Flat file, file cabinet, hanging file, and floor storage capabilities. Fire rated room. Archive File Storage Flat file, file cabinet, hanging file, and floor storage capabilities. Fire rated room. Conference Room Small conference room for up to ten (10) personnel Supply Closet Shelving for general supply storage Training Room Large room with seating and work area for up to 60 employees. -

Government Office Space Standards (GOSS) Were Prepared by the Space Standards Subcommittee of the Client Panel

G O S S J AN U AR Y 8 , 2 0 0 1 G o v e r n m e n t O f f i c e S p a c e S t a n d a r d s Province of British Columbia S P A C E T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S M A N U A L 1.0 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 3 1.1 BACKGROUND & PURPOSE ..........................................................................................................3 1.2 GOVERNMENT OFFICE SPACE STANDARDS APPLICATION ...................................................................3 1.3 INTEGRATED WORKPLACE STRATEGIES APPLICATION .......................................................................3 1.4 REPORT STRUCTURE...................................................................................................................3 2.0 STRATEGIC PRINCIPLES........................................................................... 5 2.1 CORE PRINCIPLES ......................................................................................................................5 2.2 OPERATING PRINCIPLES ..............................................................................................................5 2.3 COST CONTAINMENT PRINCIPLES .................................................................................................6 3.0 CREATING INNOVATIVE SPACE SOLUTIONS ................................................... 7 3.1 INTRODUCTION TO INTEGRATED WORKPLACE STRATEGIES (IWS).......................................................7 3.2 THE IWS PLANNING PROCESS......................................................................................................7 -

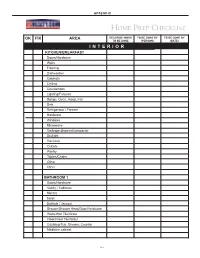

Download the Checklist

appendix Home PreP CHeCklist ok fiX area Describe work to be Done by to be Done by to be Done (Person) (Date) interior kitchen/breakfast Doors/Hardware Walls Flooring Dishwasher Cabinets Ceiling Countertops Lighting/Fixtures Range, Oven, Hood, Fan Sink Refrigerator / Freezer Hardware Windows Microwave Garbage disposal/compactor Skylight Declutter Outlets Pantry Tables/Chairs Other Other bathroom 1 Doors/Hardware Vanity / Cabinets Mirrors Toilet Bathtub / Jacuzzi Shower/Shower Head/Door/Hardware Walls/Wall Tile/Grout Floor/Floor Tile/Grout Caulking-Tub, Shower, Counter Medicine cabinet 150 appendix Home PreP CHeCklist ok fiX area Describe work to be Done by to be Done by to be Done (Person) (Date) interior bathroom 1 continued Windows Exhaust Fan Towel Bars Lighting/Fixtures Skylight Ceiling Linen Closet Towels/Shower Curtain/Bath Rug Declutter Outlets Other bathroom 2 Door/Hardware Vanity/Cabinets Mirrors Toilet Bathtub/Jacuzzi Shower/Shower Head/Door/Hardware Sinks/Faucets Walls/Wall Tile/Grout Floor/Floor Tile/Grout Caulking – Tub, Shower, Counter Medicine Cabinet Windows Exhaust Fan Towel Bars Lighting/Fixtures Skylight Ceiling Declutter Towels/Shower Curtain/Bath Rug Declutter Outlets Other 151 appendix Home PreP CHeCklist ok fiX Describe work to be Done by to be Done by to be Done (Person) (Date) area interior bathroom 3 Door/Hardware Vanity/Cabinets Mirrors Toilet Bathtub/Jacuzzi Shower/Shower Head/Door/Hardware Sinks/Faucets Walls/Wall Tile/Grout Floor/Floor Tile/Grout Caulking – Tub, Shower, Counter Medicine Cabinet Windows Exhaust