Tiers of Interventions to Prevent CLABSI

Detailed Tier 1 Interventions

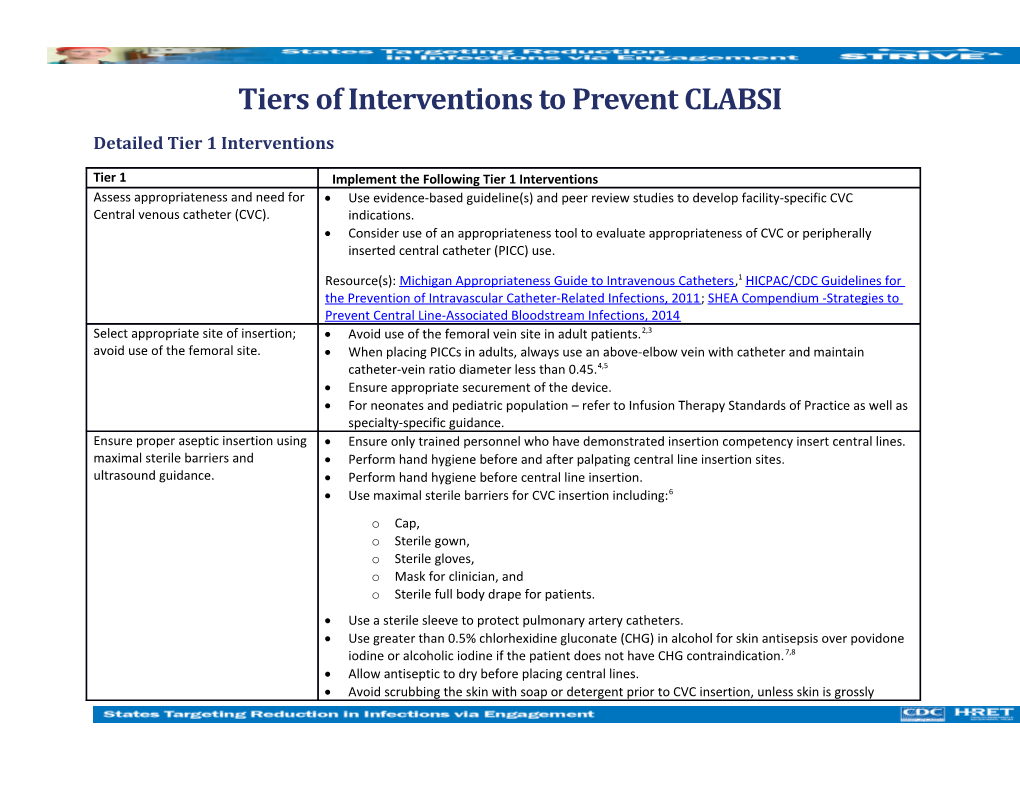

Tier 1 Implement the Following Tier 1 Interventions Assess appropriateness and need for Use evidence-based guideline(s) and peer review studies to develop facility-specific CVC Central venous catheter (CVC). indications. Consider use of an appropriateness tool to evaluate appropriateness of CVC or peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) use.

Resource(s): Michigan Appropriateness Guide to Intravenous Catheters,1 HICPAC/CDC Guidelines for the Prevention of Intravascular Catheter-Related Infections, 2011; SHEA Compendium -Strategies to Prevent Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections, 2014 Select appropriate site of insertion; Avoid use of the femoral vein site in adult patients.2,3 avoid use of the femoral site. When placing PICCs in adults, always use an above-elbow vein with catheter and maintain catheter-vein ratio diameter less than 0.45.4,5 Ensure appropriate securement of the device. For neonates and pediatric population – refer to Infusion Therapy Standards of Practice as well as specialty-specific guidance. Ensure proper aseptic insertion using Ensure only trained personnel who have demonstrated insertion competency insert central lines. maximal sterile barriers and Perform hand hygiene before and after palpating central line insertion sites. ultrasound guidance. Perform hand hygiene before central line insertion. Use maximal sterile barriers for CVC insertion including:6 o Cap, o Sterile gown, o Sterile gloves, o Mask for clinician, and o Sterile full body drape for patients. Use a sterile sleeve to protect pulmonary artery catheters. Use greater than 0.5% chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG) in alcohol for skin antisepsis over povidone iodine or alcoholic iodine if the patient does not have CHG contraindication.7,8 Allow antiseptic to dry before placing central lines. Avoid scrubbing the skin with soap or detergent prior to CVC insertion, unless skin is grossly contaminated.7 Create a standardized catheter insertion kit or cart and locate it in the patient care areas where CVC insertions are performed.9 Use ultrasound guidance for insertion of all CVCs, including PICCs.10,11,12

Use central lines with minimum number of ports or lumens essential for management of patient’s care.

Use suture-less securement devices to secure central lines.

Cover central line insertion sites with either a sterile gauze or sterile, transparent, semipermeable dressings.

Use chlorhexidine-containing dressings for non-tunneled CVCs in patients over two months of age.20,24,31 Promote a culture of safety by empowering staff to speak up and halt a procedure if a breach in practice is noted during CVC insertion.6 Periodically audit adherence with all five elements of the CVC insertion bundle. o Recent evidence suggests that if consistent use of any of the five elements is less than 75 percent, the impact on CLABSI rates will be limited. o Compliance with all five CVC bundle elements has been strongly associated with lower CLABSI rates; a 33 percent reduction in CLABSIs.13,14

Resource: AHRQ, Making Healthcare Safer II: An Updated Critical Analysis of Evidence for Patient Safety Practices. Chapter 10. Prevention of Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections: Brief Update Review

Ensure proper care and maintenance Ensure only trained personnel who have demonstrated competency maintain and access central of CVC (e.g. proper hand hygiene, lines. adequate staffing, disinfection of connector, secure/intact dressing, Perform hand hygiene prior to accessing lines or performing line care. etc.). Ensure appropriate nurse-to-patient ratio and limit the use of float nurses in intensive care units (ICUs).15 Access catheters only with sterile devices. Perform vigorous, mechanical scrub for manual disinfection of needleless connectors/hubs/injection ports with an appropriate antiseptic (e.g., chlorhexidine, povidone iodine, an iodophor, 70 percent alcohol) prior to each access and allow drying. Apply mechanical friction for no less than five seconds to reduce contamination.30 Minimize interruption of lines (e.g., tubing disconnects, flushing, manipulation) during use.4 Use aseptic technique to change dressings at established intervals and immediately if the dressing integrity becomes damp, loosened, visibly soiled or if moisture, drainage or blood are present under the dressing.4 Prepare clean skin with greater than 0.5 percent chlorhexidine with alcohol for dressing changes. o If chlorhexidine is contraindicated, use a tincture of iodine, an iodophor or 70 percent alcohol. Monitor insertion sites daily, either visually during dressing changes or by palpation through intact dressing for tenderness or other signs of infection. Change administration sets, tubing and needless components at a frequency consistent with guidelines.4,8,20 Periodically audit adherence with care and maintenance practices and feedback findings to personnel.

Resource(s): TAP CLABSI Implementation Guide –Links to Example Resources. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC.

Optimize prompt removal of clinically Optimize prompt removal of CVC and PICCs by applying clinical criteria for line use. If criteria are unnecessary CVCs. not met, remove the CVC.1,4,16,17 Criteria for continued use of CVC may include: 4 o Clinical instability (altered vital signs, oxygen saturation), o Continuous infusion therapy (parenteral nutrition, fluid and electrolytes, blood/blood products), o Hemodynamic monitoring, o Intermittent infusion therapy, and/or o Documented history of difficult peripheral venous access.

Perform unit level audits to assess central line utilization. o Use a database (e.g., NHSN) to evaluate and track catheter dwell time by unit to identify outliers.

3 o For units that are outliers, investigate whether central lines can be removed without affecting patient care.

Review and audit compliance with Tier 1 measures before moving to Tier 2

Detailed Tier 2 Interventions

Tier 2 Implement the Following Tier 2 Interventions if CLABSI Incidence Remains Elevated Perform needs assessment with Perform needs assessment using the CLABSI Guide to Patient Safety. Adapted from the validated CLABSI Guide to Patient Safety (GPS). CAUTI Guide to Patient Safety (GPS), the CLABSI GPS is a brief trouble-shooting guide for hospitals, designed to identify the key reasons why hospitals may not be successful in preventing infections.18,19

Use GPS results to engage health care personnel in the process of developing next steps to prevent CLABSI.

CLABSI GPS questions:

1. Do you currently have a well-functioning team (or work group) focusing on CLABSI prevention? 2. Do you have a project manager with dedicated time to coordinate your CLABSI prevention activities? 3. Do you have an effective nurse champion for your CLABSI prevention activities? 4. Does your facility use a standardized central vascular catheters (CVC) insertion tray that includes chlorhexidine gluconate for skin antisepsis? 5. Do nurses stop a CVC insertion if aseptic insertion technique is not being followed? 6. Do bedside nurses take initiative and contact physicians to ensure that CVCs are removed when the device is no longer needed? 7. Do bedside nurses assess dressing integrity and replace loose, wet, soiled dressings on vascular catheters on a daily basis? 8. Do you have an effective physician champion for your CLABSI prevention activities? 9. Is senior leadership supportive of CLABSI prevention activities? 10. Do you currently collect any CLABSI-related data (e.g., CVC prevalence, CVC days, and/or CLABSI rates)? 11. Do you routinely feed back any CLABSI-related data to frontline staff (e.g., CVC prevalence, CVC days and/or rates of CLABSI)? 12. At your facility, do patients and/or families request CVCs such as PICCs? 13. At your facility, are CVCs such as PICCs being inserted without an appropriate indication?

Resource(s): Visit https://catheterout.org/?q=gps to access the online CAUTI GPS tool. Conduct multidisciplinary rounds to Audit CVC necessity for continued use during multidisciplinary rounds on a daily basis. audit for necessity of continued CVC Remove catheters not required for patient care.1,4,20 use. Resource: The Joint Commission CLABSI Toolkit – Preventing Central-Line Associated Bloodstream Infections: Useful Tools, An International Perspective

Feed back CLABSI and CVC utilization Nurse and physician leaders should work with infection prevention to share feedback about metrics to frontline staff in "real- individual infections as they are identified (“real-time”) with the health care personnel. time." Share CLABSI and CVC utilization data trends on an ongoing basis with frontline staff. Consider posting unit-specific and hospital-wide rates, for comparison and benchmarking, in highly visible areas for health care personnel to review. Observe and document competency Ensure health care personnel placing CVCs have received initial and recurrent competency-based and compliance with CVC insertion training and education for safe placement of CVCs.4,8,21,22,23 Training should include simulation- and maintenance. based learning and demonstrations of competency. Ensure health care personnel responsible for maintenance of CVCs have received initial and recurrent training and demonstrate competence in use of maintenance supplies and procedures. Use additional approaches as Additional approaches are recommended when CLABSI rates remain elevated despite indicated by risk assessment (e.g. implementation of basic CLABSI prevention strategies. antimicrobial coated CVC). o Bathe ICU patients over two months of age with a chlorhexidine preparation on a daily basis. (Note, the role of chlorhexidine bathing in non-ICU patients remains to be determined.)20 o Use antiseptic-containing hub/connectors or cap/port protectors to cover CVC line connectors.20,32 o For short term CVCs, try using silver sulfadiazine-CHG or minocycline-rifampin coated catheters for catheters expected to be in place for more than five days. 25,26,27

5 o For long term CVCs, try using antimicrobial lock solution or minocycline-rifampin coated silicone catheters.27,28

Prior to implementing any of these approaches, perform a CLABSI risk assessment, reviewing potential adverse events and cost impacts. Full or mini root-cause analysis of Conduct in-depth review of infections to identify contributing factors and root-causes. CLABSI Analyze results to determine improvement steps. Share results of analysis with health care personnel and hospital leadership. Resource(s): AHRQ CUSP Learning from Defect tool

Resource(s)

APIC Implementation Guide. Guide to Preventing Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections. Association for Professional in Infection Prevention and Control, APIC. 2015. Available at http://apic.org/Resource_/TinyMceFileManager/2015/APIC_CLABSI_WEB.pdf

Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infection Toolkit. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC. Accessed at http://www.cdc.gov/hai/bsi/bsi.html

HICPAC/CDC Guidelines for the Prevention of Intravascular Catheter-Related Infections, 2011. Available at http://www.ajicjournal.org/article/S0196-6553(11)00085-X/pdf Learn from Defects Tool. Content last reviewed December 2012. Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research, Rockville MD. Available at http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/education/curriculum-tools/cusptoolkit/toolkit/learndefects.html Making Health Care Safer II: An Updated Critical Analysis of the Evidence for Patient Safety Practices, Chapter 10 Prevention of Central Line- Associated Bloodstream Infections: Brief Update Review. Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research. 2013; 89-109. Accessed at http://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/research/findings/evidence-based-reports/services/quality/ptsafetyII-full.pdf

Michigan Appropriateness Guide to Intravenous Catheters. Annals of Internal Medicine. Available at http://annals.org/aim/article/2436759/michigan-appropriateness-guide-intravenous-catheters-magic-results-from-multispecialty-panel SHEA Strategies to Prevent Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections in Acute Care Hospitals: 2014 Update. Society of Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/10.1086/676533.pdf?refreqid=excelsior %3Aeba0bd233c501ffb417a25b13df1f86a TAP CLABSI Implementation Guide – Links to Example Resources. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/hai/prevent/tap/clabsi.html. The Joint Commission CLABSI Toolkit – Preventing Central-Line Associated Bloodstream Infections: Useful Tools, an International Perspective. Accessed at https://www.jointcommission.org/topics/clabsi_toolkit.aspx

7 References

1. Chopra V, Flanders S, Saint S, et al. The Michigan Appropriateness Guide for Intravenous Catheters (MAGIC): Results from a Multispecialty Panel Using the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method. Ann Itern Med. 2015; 163(6 Suppl): S1-40. 2. Parienti J, Mongardon N, Mégarbane B, et al. Intravascular Complications of Central Venous Catheterization by Insertion Site, N Engl J Med. 2015; 373(13):1220-9. 3. Parienti J, du Cheyron D, Timsit JF, et al. Meta-analysis of subclavian insertion and nontunneled central venous catheter-associated infection risk reduction in critically ill adults. Crit Care Med. 2012; 40(5):1627-34. 4. Gorski L, Hadaway L, Hagel M, McGoldrick M, Orr M, Doellman D. Infusion Therapy, Standards of Practice, 2016 update. Journal of Infusion Nursing. 2016; www.ins1.org. 5. Sharp R, Cummings M, Fielder A, et al. The Catheter to Vein Ratio and Rates of Symptomatic Venous Thromboembolism in Patients with a Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter (PICC): A Prospective Cohort Study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015; 52(3):677-85. 6. Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, et al. An Intervention to Decrease Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355(26):2725-32. 7. Mimoz O, Lucet JC, Kerforne T, Pascal J, Souweine B, Goudet V, et al. Skin Antisepsis with Chlorhexidine–Alcohol Versus Povidone Iodine– Alcohol, With and Without Skin Scrubbing, For Prevention of Intravascular-Catheter-Related Infection (CLEAN): An Open-Label, Multicentre, Randomised, Controlled, Two-By-Two Factorial Trial. Lancet. 2015; 386(10008): 2069–77. 8. O’Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, et al. Guidelines for Prevention of Intravascular Catheter-Related Infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2011; 52(9):e162-93. 9. Chopra V, Krein SL, Olmsted RN, Safdar N, Saint S. Chapter 10. Prevention of Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections: Brief Update Review. Making Health Care Safer II: An Updated Critical Analysis of the Evidence for Patient Safety Practices. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 211. (Prepared by the Southern California-RAND Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-2007-10062-I.) AHRQ Publication No. 13-E001-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. March 2013. www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/evidence-based-reports/ptsafetyuptp.html. 10. Moureau N, Lamperti M, Kelly LJ, et al. Evidence-Based Consensus on the Insertion of Central Venous Access Devices: Definition of Minimal Requirements for Training. Br J Anaesth. 2013; 110(3):347-56. 11. Lamperti M, Bodenham AR, Pittiruti M, et al. International Evidence-Based Recommendations on Ultrasound-Guided Vascular Access. Intensive Care Med. 2012; 38(7):1105-17. 12. Bodenham A, Babu S, Bennett J, et al. Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland: Safe Vascular Access 2016. Anaesthesia. 2016; 71(5):573-85. 13. Furuya EY, Dick AW, Herzig CT, Pogorzelska-Maziarz M, Larsen EL, Stone PW. Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infection Reduction and Bundle Compliance in Intensive Care Units: A National Study. Infect Control Hosp Epdiemiol. 2016; 37(7):805-10. 14. O'Neill C, Ball K, Wood H, et al. A Central Line Care Maintenance Bundle for the Prevention of Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infection in Non-Intensive Care Unit Settings. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016; 37(6):692-8. 15. Kane RL, Shamliyan TA, Muella C, Duval S, Wilt, TJ. The Association of Registered Nurse Staffing Levels and Patient Outcomes: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Med Care. 2007; 45(12):1195-204. 16. Mazi W, Begum Z, Abdulla D, et. Al. Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infection in a Trauma Intensive Care Unit: Impact of Implementation of Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America/Infectious Diseases Society of America Practice Guidelines. Am J Infect Control. 2014; 42(8):865-7. 17. Walz JM, Ellison RT, Mack DA, et al. The Bundle "plus": The Effect of a Multidisciplinary Team Approach to Eradicate Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections. Anesth Analg. 2015; 120(4):868-76. 18. Saint S, Gaies E, Fowler KE, Harrod M, Krein S. Introducing a Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection (CAUTI) Prevention Guide to Patient Safety (GPS). Am J Infect Control. 2014; 42(5), 548-50. 19. Fletcher KE, Tyszka JT, Harrod M, Fowler KE, Saint S, Krein S. Qualitative Validation of the CAUTI Guide to Patient Safety Assessment Tool. Am J Infect Control. 2016; 44(10):1102-09. 20. Marschall J, Mermel LA, Fakih M, et al. Strategies to Prevent Central Line–Associated Bloodstream Infections in Acute Care Hospitals: 2014 Update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014; 35(7):753-71. 21. Steiner M, Langgartner M, Cardona F, et al. Significant Reduction of Catheter-associated Blood Stream Infections in Preterm Neonates After Implementation of a Care Bundle Focusing on Simulation Training of Central Line Insertion. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015; 34(11):1193-6. 22. Allen GB, Miller GB, Hess S, et al. A Multitiered Strategy of Simulation Training, Kit Consolidation, and Electronic Documentation is Associated with a Reduction in Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections. Am J Infect Control. 2014; 42(6):643-8. 23. Peltan ID, Shiga T, Gordan JA, Currier PF. Simulation Improves Procedural Protocol Adherence During Central Venous Catheter Placement: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Simul Healthc. 2015; 10(5):270-6. 24. Timsit JF, Mimoz O, Mourvillier B, et al. Randomized Controlled Trial of Chlorhexidine Dressing and Highly Adhesive Dressing for Preventing Catheter-Related Infections in Critically Ill Adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012; 186(12):1272-8. 25. Rupp ME, Lisco SJ, Lipsett PA, et al. Effect of a Second-Generation Venous Catheter Impregnated with Chlorhexidine and Silver Sulfadiazine on Central Catheter-Related Infections: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005; 143(8):570-80. 26. Lorente L, Lecuona M, Jimenez A, et al. Chlorhexidine-silver Sulfadiazine– or Rifampicin-Miconazole–Impregnated Venous Catheters Decrease the Risk of Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infection Similarly. Am J Infect Control. 2016; 44(1):50–3.

9 27. Lai NM, Chaiyakunapruk N, Lai NA, O’Riordan E, Pau WS, Saint S. Catheter Impregnation, Coating or Bonding for Reducing Central Venous Catheter-Related Infections in Adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016; 3:CD007878. 28. Zacharioudakis IM, Zervou FN, Arvantis M, et al. Antimicrobial Lock Solutions as a Method to Prevent Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis. 201; 59(12):1741-9. 29. Septimus E, Hickok J, Moody J, et al. Closing the Translation Gap: Toolkit-based Implementation of Universal Decolonization in Adult Intensive Care Units Reduces Central Line-associated Bloodstream Infections in 95 Community Hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2016; 63(2):172-7. 30. Rupp ME, Yu S, Huerta T, et al. Adequate disinfection of a split-septum needleless intravascular connector with a 5- second alcohol scrub. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol.2012; 33(7): 661–5. 31. Timsit JF, Schwebel C, Bouadma L, et al. Chlorhexidine-Impregnated Sponges and Less Frequent Dressing Changes for Prevention of Catheter-Related Infections in Critically Ill Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2009; 301(12):1231-41. 32. Wright MO, Tropp J, Schora DM, et al. Continuous Passive Disinfection of Catheter Hubs Prevents Contamination and Bloodstream Infection. Am J Infect Control. 2013; 41(1):33-8.