© 2012 Marlia Fontaine-Weisse All Rights Reserved

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

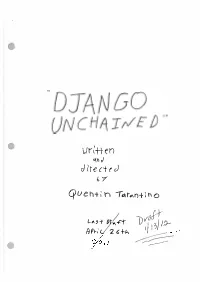

Django Unchained (2012) Screenplay

' \Jl't-H- en �'1 J drtecitJ b/ qu eh+; h -r�r... n+ l ho ,r Lo\5-t- () .<..+-t vof I 3/ I;)-- ftp�;L 2 t 1-h 1) \ I ' =------- I EXT - COUNTRYSIDE - BROILING HOT DAY As the film's OPENING CREDIT SEQUENCE plays, complete with its own SPAGHETTI WESTERN THEME SONG, we see SEVEN shirtless and shoeless BLACK MALE SLAVES connected together with LEG IRONS, being run, by TWO WHITE MALE HILLBILLIES on HORSEBACK. The location is somewhere in Texas. The Black Men (ROY, BIG SID, BENJAMIN, DJANGO, PUDGY RALPH, FRANKLYN, and BLUEBERRY) are slaves just recently purchased at The Greenville Slave Auction in Greenville Mississippi. The White Hillbillies are two Slave Traders called, The SPECK BROTHERS (ACE and DICKY). One of the seven slaves is our hero DJANGO.... he's fourth in the leg iron line. We may or may not notice a tiny small "r" burned into his cheek ("r" for runaway), but we can't help but notice his back which has been SLASHED TO RIBBONS by Bull Whip Beatings. As the operatic Opening Theme Song plays, we see a MONTAGE of misery and pain, as Django and the Other Men are walked through blistering sun, pounding rain, and moved along by the end of a whip. Bare feet step on hard rock, and slosh through mud puddles. Leg Irons take the skin off ankles. DJANGO Walking in Leg Irons with his six Other Companions, walking across the blistering Texas panhandle .... remembering... thinking ... hating .... THE OPENING CREDIT SEQUENCE end. EXT - WOODS - NIGHT It's night time and The Speck Brothers, astride HORSES, keep pushing their black skinned cargo forward. -

Vermont Commons School Summer Reading List 2011

Vermont Commons School Summer Reading List 2011 . 2011Common Texts: 7th and 8th Grades: To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee 9th, 10th, 11th, and 12th Grades: A Stranger in the Kingdom by Howard Frank Mosher Dear Parents, Students, and Friends, The Language Arts Department is excited to share this year’s Common Text selections, the Summer Reading Lists, and assignments. Our Common Texts this year are To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee, for 7th and 8th grades and A Stranger in the Kingdom by Howard Frank Mosher, for 9th, 10th, 11th, and 12th grades. Vermont Commons wants to join with the Vermont Council on the Humanities to celebrate the 50th Anniversary of Harper Lee’s class novel of innocence, prejudice, and the moral awakening of a young girl. Mosher’s novel is a perfect partner book to Lee’s as it depicts similar themes and targets an older audience. Students will read about diversity in each text and will be involved in activities surrounding this theme throughout the year. Once again, we’ve divided the reading list into three categories: (1) Classics and Prize Winners (2) Books that Speak to the VCS Mission Statement (3) Other Books for Summer. We are asking students to choose a book from two of the categories, as well as the Common Text, for a total of three books to be read this summer. Finally, some students have asked for quick summaries of the books on our list, so we have provided some short descriptions at the end of the lists. For more summaries, we encourage students to browse the bookstore or an online bookseller such as Barnes & Noble.com. -

THE WALTER STANLEY CAMPBELL COLLECTION Inventory and Index

THE WALTER STANLEY CAMPBELL COLLECTION Inventory and Index Revised and edited by Kristina L. Southwell Associates of the Western History Collections Norman, Oklahoma 2001 Boxes 104 through 121 of this collection are available online at the University of Oklahoma Libraries website. THE COVER Michelle Corona-Allen of the University of Oklahoma Communication Services designed the cover of this book. The three photographs feature images closely associated with Walter Stanley Campbell and his research on Native American history and culture. From left to right, the first photograph shows a ledger drawing by Sioux chief White Bull that depicts him capturing two horses from a camp in 1876. The second image is of Walter Stanley Campbell talking with White Bull in the early 1930s. Campbell’s oral interviews of prominent Indians during 1928-1932 formed the basis of some of his most respected books on Indian history. The third photograph is of another White Bull ledger drawing in which he is shown taking horses from General Terry’s advancing column at the Little Big Horn River, Montana, 1876. Of this act, White Bull stated, “This made my name known, taken from those coming below, soldiers and Crows were camped there.” Available from University of Oklahoma Western History Collections 630 Parrington Oval, Room 452 Norman, Oklahoma 73019 No state-appropriated funds were used to publish this guide. It was published entirely with funds provided by the Associates of the Western History Collections and other private donors. The Associates of the Western History Collections is a support group dedicated to helping the Western History Collections maintain its national and international reputation for research excellence. -

Sartor Resartus: the Life and Opinions of Herr Teufelsdröckh

Sartor Resartus The Life and Opinions of Herr Teufelsdröckh Thomas Carlyle This public-domain (U.S.) text was scanned and proofed by Ron Burkey. The Project Gutenberg edition (“srtrs10”) was subse- quently converted to LATEX using GutenMark software and re-edited with lyx software. The frontispiece, which was not included in the Project Gutenberg edition, has been restored. Report problems to [email protected]. Revi- sion B1 differs from B0a in that “—-” has ev- erywhere been replaced by “—”. Revision: B1 Date: 01/29/2008 Contents BOOK I. 3 CHAPTER I. PRELIMINARY. 3 CHAPTER II. EDITORIAL DIFFICULTIES. 11 CHAPTER III. REMINISCENCES. 17 CHAPTER IV. CHARACTERISTICS. 33 CHAPTER V. THE WORLD IN CLOTHES. 43 CHAPTER VI. APRONS. 53 CHAPTER VII. MISCELLANEOUS-HISTORICAL. 57 CHAPTER VIII. THE WORLD OUT OF CLOTHES. 63 CHAPTER IX. ADAMITISM. 71 CHAPTER X. PURE REASON. 79 i ii CHAPTER XI. PROSPECTIVE. 87 BOOK II. 101 CHAPTER I. GENESIS. 101 CHAPTER II. IDYLLIC. 113 CHAPTER III. PEDAGOGY. 125 CHAPTER IV. GETTING UNDER WAY. 147 CHAPTER V. ROMANCE. 163 CHAPTER VI. SORROWS OF TEUFELSDRÖCKH. 181 CHAPTER VII. THE EVERLASTING NO. 195 CHAPTER VIII. CENTRE OF INDIFFERENCE. 207 CHAPTER IX. THE EVERLASTING YEA. 223 CHAPTER X. PAUSE. 239 BOOK III. 251 CHAPTER I. INCIDENT IN MODERN HISTORY. 251 CHAPTER II. CHURCH-CLOTHES. 259 iii CHAPTER III. SYMBOLS. 265 CHAPTER IV. HELOTAGE. 275 CHAPTER V. THE PHOENIX. 281 CHAPTER VI. OLD CLOTHES. 289 CHAPTER VII. ORGANIC FILAMENTS. 295 CHAPTER VIII. NATURAL SUPERNATURALISM. 307 CHAPTER IX. CIRCUMSPECTIVE. 323 CHAPTER X. THE DANDIACAL BODY. 329 CHAPTER XI. TAILORS. 349 CHAPTER XII. FAREWELL. 355 APPENDIX. -

Fasig-Tipton

Barn E2 Hip No. Consigned by Roger Daly, Agent 1 Perfect Lure Mr. Prospector Forty Niner . { File Twining . Never Bend { Courtly Dee . { Tulle Perfect Lure . Baldski Dark bay/br. mare; Cause for Pause . { *Pause II foaled 1998 {Causeimavalentine . Bicker (1989) { Iza Valentine . { Countess Market By TWINING (1991), [G2] $238,140. Sire of 7 crops, 23 black type win- ners, 248 winners, $17,515,772, including Two Item Limit (7 wins, $1,060,585, Demoiselle S. [G2], etc.), Pie N Burger [G3] (to 6, 2004, $912,133), Connected [G3] ($525,003), Top Hit [G3] (to 6, 2004, $445,- 357), Tugger ($414,920), Dawn of the Condor [G2] ($399,615). 1st dam CAUSEIMAVALENTINE, by Cause for Pause. 2 wins at 3, $28,726. Dam of 4 other foals of racing age, including a 2-year-old of 2004, one to race. 2nd dam Iza Valentine, by Bicker. 5 wins, 2 to 4, $65,900, 2nd Las Madrinas H., etc. Half-sister to AZU WERE. Dam of 11 winners, including-- FRAN’S VALENTINE (f. by Saros-GB). 13 wins, 2 to 5, $1,375,465, Santa Susana S. [G1], Kentucky Oaks [G1], Hollywood Oaks [G1]-ntr, Santa Maria H. [G2], Chula Vista H. [G2], Las Virgenes S. [G3], Princess S. [G3], Yankee Valor H. [L], B. Thoughtful H. (SA, $27,050), Dulcia H. (SA, $27,200), Black Swan S., Bustles and Bows S., 2nd Breeders’ Cup Distaff [G1], Hollywood Starlet S.-G1, Alabama S. [G1], etc. Dam of 5 winners, including-- WITH ANTICIPATION (c. by Relaunch). 15 wins, 2 to 7, placed at 9, 2004, $2,660,543, Sword Dancer Invitational H. -

2020 International List of Protected Names

INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (only available on IFHA Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 03/06/21 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne-Billancourt, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org The list of Protected Names includes the names of : Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally renowned, either as main stallions and broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or jump) From 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf Since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf The main stallions and broodmares, registered on request of the International Stud Book Committee (ISBC). Updates made on the IFHA website The horses whose name has been protected on request of a Horseracing Authority. Updates made on the IFHA website * 2 03/06/2021 In 2020, the list of Protected -

Rio Grande's Last Race and Other Verses

Rio Grande's Last Race and Other Verses Paterson, Andrew Barton (1864-1941) University of Sydney Library Sydney 1997 http://setis.library.usyd.edu.au/ © University of Sydney Library. The texts and Images are not to be used for commercial purposes without permission Source Text: Prepared against the print edition published by Angus and Robertson, Melbourne 1902 Scanned text file available at Project Gutenberg, prepared by Alan R.Light. Encoding of the text file at was prepared against first edition of 1902, including page references and other features of that work. Advertising material has been removed from the digital version.The original Gutenberg text file is available from this site at http://setis.library.usyd.edu.au/texts/rlast10.txt All quotation marks retained as data. All unambiguous end-of-line hyphens have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line. First Published: 1902 Australian Etexts poetry 1890-1909 verse A.B. Paterson Portrait Photograph The verses in this collection have appeared in papers in various parts of the world — "Rio Grande" in the London SKETCH; most of the war verses in the Bloemfontein FRIEND; others in the Sydney BULLETIN, COMMONWEALTH ANNUAL, SYDNEY MAIL, and PASTORALIST'S REVIEW: and the author's acknowledgements are due to the proprietors of those papers. A. B. PATERSON. CONTENTS RIO GRANDE'S LAST RACE Now this was what Macpherson told - 1 BY THE GREY GULF-WATER Far to the Northward there lies a land, - 7 WITH THE CATTLE The drought is down on field and flock, -

Asr^Jbgas-** !£Sssssas Ssasn.Sszsz

la *hla f koraea it that time; bat we believe we trr Hlr John Johnstone, who. in taking a drop-fence very little understood, and THE OF AHEBICA. THE TURF IN ENGLAND. ¦ear Btelchky, Staffordshire, the other day, *u on- UFB IH8UBAHCE. information Is apt to leao to some H0ESE8 conrM in saying that they hare mora titan doubled of to the prejudice or life misimdersuan^ 10 a to I860 fracturing hw collar bona a tw^ber. price, ud that Itondrad dollar bone his rib# Toe honorable Baronet wax removed hither Haw life lM>ruci C-Hrt. every building lnaured by a^ora°J?i;r-n??p^ipanylire Tkflr Prcwnt Value, with SeeewUese W'auld above in una marine now. FIMI OM IffM CONESPONKIT. rail and houae in Belgrava waa certain to be oonaumedmaurauc-^ forty bring $200 per conveyed to hw own Sjm-tM it la M to Breeding for Speed for Ike Km4 m< difficult lor oonaua enume¬ Ike (>ru< m4 square. where death put a period to his sufferings on jeara, eae* to aee that the ..?of"5a***?*. 1*1 however, NtdMal Mc«pl« Chut, Put the 8Mb Inst. Hlr follower of ud HaUettawr-Iaeaas** inaumnoe would be aua Track. rators to the value of horaes in other than IHuktt. John wm a veteran i««Ma mat the greatly to give any Praeit->M«TCMiu la the D*1mi the hounds, having imbibed a love for the chaae in AKM-CMt «r Life #^e"*rml""" company would not Among tUo great industrial intereata of tbla coun¬ a general way, as none other than an expert in the Cheater Cap, the Two Thoaaaad his youth which he cherished and carried luto the ,"WMC*rPrf. -

Royal Ascot 1953

r" ROYAL ASCOT 1953 Third Day Royal Ascot (Under the Rules of Racing) THIRD DAY: 18th JUNE 1953 Official Programme ONE SHILLING Stewards The DUKE OF NORFOLK, K.G., G.c.v.o. The VISCOUNT ALLENDALE, K.G., C.B.E., M.C. The EARL OF DERBY, M.c. The EARL OF SEFTON. Stewards' Secretaries Brigadier C. B. HARVEY Brigadier J. Le C. FOWLE Mr. P. BROOKE. Officials Messrs. WEATHERBY & SONS, Secretaries. Mr. G. H. FREER, Handicapper. Mr. A. MARSH, Starter. Mr. MALCOLM HANCOCK, Judge. Mr. J. F. CHARLES MANNING, Clerk of the Scales. Veterinary Officers: Lt.-Col. J. BELL, M.R.C.V.S., and Lt.-Col. R. H. KNOWLES, M.R.C.V.S. Medical Officers: G. S. HALLEY, M.D., M.R.C.P., E. C. MALDEN, c.v.o., M.B., B.CH., R. W. L. MAY, M.B., B.CH., and J. M. BROWN, F.R.C.S. Mr. H. BELL, M.R.C.V.S., Veterinary Surgeon. Major J. C. BULTEEL, D.S.O., M.C., Clerk of the Course. Thursday Published by Authority of the Clerk of the Course and printed by Welbecson Press Ltd 39-43 Battersea High Street SW11 2 3Q—FIRST RACE 6 FURLONGS —THE CORK AND ORRERY STAKES . 5 sov. each, and 10 sov. extra unless forfeit be declared by Tuesday, June 9th, with 1200 sov. added, for three yrs old, 7st 121b, four and upwards, 8st 111b; mares allowed 51b; maiden three yrs old allowed 41b, four and upwards, 81b; a winner, after 1951, Form of Horses engaged in The Gold Cup of a race or races amounting together to the following amounts to carry—of 500 sov., 31b; of 750 sov., 61b; of 1000 sov., 101b; of 2000 sov., 141b extra; the second to receive 10 per cent and the third 5 per cent of the whole stakes; six furlongs (44 entries, forfeit AQUINO II—19.6.52—Won Gold Cup at Ascot, 2-J- miles, with Eastern Emperor 3 declared for 28).—Closed April 14th, 1953. -

Personal and Communal Recollections of Maritime Life in Jizan and the Farasan Islands, Saudi Arabia

J Mari Arch DOI 10.1007/s11457-016-9159-2 ORIGINAL PAPER Remembering the Sea: Personal and Communal Recollections of Maritime Life in Jizan and the Farasan Islands, Saudi Arabia Dionisius A. Agius1 · John P. Cooper1 · Lucy Semaan2 · Chiara Zazzaro3 · Robert Carter4 © The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract People create narratives of their maritime past through the remembering and forgetting of seafaring experiences, and through the retention and disposal of maritime artefacts that function mnemonically to evoke or suppress those experiences. The suste- nance and reproduction of the resulting narratives depends further on effective media of intergenerational transmission; otherwise, they are lost. Rapid socio-economic transfor- mation across Saudi Arabia in the age of oil has disrupted longstanding seafaring economies in the Red Sea archipelago of the Farasan Islands, and the nearby mainland port of Jizan. Vestiges of wooden boatbuilding activity are few; long-distance dhow trade with South Asia, the Arabian-Persian Gulf and East Africa has ceased; and a once substantial pearling and nacre (mother of pearl) collection industry has dwindled to a tiny group of hobbyists: no youth dive today. This widespread withdrawal from seafaring activity among many people in these formerly maritime-oriented communities has diminished the salience of such activity in cultural memory, and has set in motion narrative creation processes, through which memories are filtered and selected, and objects preserved, discarded, or lost. This paper is a product of the encounter of the authors with keepers of maritime memories and objects in the Farasan Islands and Jizan. -

·E.R. Cross 1913-2000 Remembrances of a Master Diver 2001 Dive Industry Awards Gala

Historical Diver, Volume 8, Issue 4 [Number 25], 2000 Item Type monograph Publisher Historical Diving Society U.S.A. Download date 09/10/2021 08:18:56 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/30867 The Official Publication of The Historical Diving Societies of Australia & S.E. Asia, Canada, Germany, Mexico and the U.S.A. Volume 8 Issue 4 Fall2000 ..... - ~ ·E.R. Cross 1913-2000 Remembrances of a Master Diver 2001 Dive Industry Awards Gala Dive Industry Awards Gala HDSUSA E.R. Cross Award Sidney Macken Historical Diver Magazine Pioneer Award Dr. Christian J. Lambertsen Academy of Underwater Arts and Sciences - 2000 NOGI Awards Ada Rebikoff, Arts John E. Randall, Science Tom Mount, Sports/Education Frederick Dumas, Distinguished Service DEMA Reaching Out Award James Cahill Ike Brigham Dave Taylor These Awards will be presented at the 2nd Annual Dive Industry Awards Gala. Information and tickets are available from DEMA at 858-616-6408 When: Friday, January 26th, 2001 Where: New Orleans Marriott 5:30p.m. - Hors d'oeuvres & Silent Auction 7:00p.m. -Dinner & Awards Ceremony (Black Tie Optional) Individual= $125.00- Couple= $225.00 (Seating will be limited and price will be in effect until December 31, 2000 Ticket requests received after January I, 2001 will increase $25.00 per ticket purchase.) 2 HISTORICAL DIVER Vol. 8 Issue 4 Fall2000 HISTORICAL DIVING SOCIETY USA A PUBLIC BENEFIT NONPROFIT CORPORATION 340 S KELLOGG AVE STE E, GOLETA CA 93117, U.S.A. PHONE: 805-692-0072 FAX: 805-692-0042 e-mail: [email protected] or HTTP:IIwww.hds.orgl Corporate Members ADVISORY BOARD Sponsors D.E.S.C.O.