Extensional Tectonics in the North Atlantic Caledonides: a Regional View

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Part 3: Normal Faults and Extensional Tectonics

12.113 Structural Geology Part 3: Normal faults and extensional tectonics Fall 2005 Contents 1 Reading assignment 1 2 Growth strata 1 3 Models of extensional faults 2 3.1 Listric faults . 2 3.2 Planar, rotating fault arrays . 2 3.3 Stratigraphic signature of normal faults and extension . 2 3.4 Core complexes . 6 4 Slides 7 1 Reading assignment Read Chapter 5. 2 Growth strata Although not particular to normal faults, relative uplift and subsidence on either side of a surface breaking fault leads to predictable patterns of erosion and sedi mentation. Sediments will fill the available space created by slip on a fault. Not only do the characteristic patterns of stratal thickening or thinning tell you about the 1 Figure 1: Model for a simple, planar fault style of faulting, but by dating the sediments, you can tell the age of the fault (since sediments were deposited during faulting) as well as the slip rates on the fault. 3 Models of extensional faults The simplest model of a normal fault is a planar fault that does not change its dip with depth. Such a fault does not accommodate much extension. (Figure 1) 3.1 Listric faults A listric fault is a fault which shallows with depth. Compared to a simple planar model, such a fault accommodates a considerably greater amount of extension for the same amount of slip. Characteristics of listric faults are that, in order to maintain geometric compatibility, beds in the hanging wall have to rotate and dip towards the fault. Commonly, listric faults involve a number of en echelon faults that sole into a lowangle master detachment. -

Kinematics of the Northern Walker Lane: an Incipient Transform Fault Along the Pacific–North American Plate Boundary

Kinematics of the northern Walker Lane: An incipient transform fault along the Paci®c±North American plate boundary James E. Faulds Christopher D. Henry Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, MS 178, University of Nevada, Reno, Nevada 89557, USA Nicholas H. Hinz ABSTRACT GEOLOGIC SETTING In the western Great Basin of North America, a system of dextral faults accommodates As western North America has evolved 15%±25% of the Paci®c±North American plate motion. The northern Walker Lane in from a convergent to a transform margin in northwest Nevada and northeast California occupies the northern terminus of this system. the past 30 m.y., the northern Walker Lane has This young evolving part of the plate boundary offers insight into how strike-slip fault undergone widespread volcanism and tecto- systems develop and may re¯ect the birth of a transform fault. A belt of overlapping, left- nism. Tertiary volcanic strata include 31±23 stepping dextral faults dominates the northern Walker Lane. Offset segments of a W- Ma ash-¯ow tuffs associated with the south- trending Oligocene paleovalley suggest ;20±30 km of cumulative dextral slip beginning ward-migrating ``ignimbrite ¯are up,'' 22±5 ca. 9±3 Ma. The inferred long-term slip rate of ;2±10 mm/yr is compatible with global Ma calc-alkaline intermediate-composition positioning system observations of the current strain ®eld. We interpret the left-stepping rocks related to the ancestral Cascade arc, and faults as macroscopic Riedel shears developing above a nascent lithospheric-scale trans- 13 Ma to present bimodal rocks linked to Ba- form fault. -

Late Mesozoic Compressional to Extensional Tectonics in The

Late Mesozoic compressional to extensional tectonics in the Yiwulüshan massif, NE China and its bearing on the evolution of the Yinshan-Yanshan orogenic belt: Part I: Structural analyses and geochronological constraints Wei Lin, Michel Faure, Yan Chen, Wenbin Ji, Fei Wang, Lin Wu, Nicolas Charles, Jun Wang, Qingchen Wang To cite this version: Wei Lin, Michel Faure, Yan Chen, Wenbin Ji, Fei Wang, et al.. Late Mesozoic compressional to extensional tectonics in the Yiwulüshan massif, NE China and its bearing on the evolution of the Yinshan-Yanshan orogenic belt: Part I: Structural analyses and geochronological constraints. Gond- wana Research, Elsevier, 2013, 23 (1), pp.54-77. 10.1016/j.gr.2012.02.013. insu-00681290 HAL Id: insu-00681290 https://hal-insu.archives-ouvertes.fr/insu-00681290 Submitted on 21 Aug 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Late Mesozoic compressional to extensional tectonics in the Yiwulüshan massif, NE China and its bearing on the evolution of the Yinshan–Yanshan orogenic belt: Part I: Structural analyses and geochronological constraints Wei Lina Michel Faureb Yan Chenb Wenbin Jia Fei Wanga Lin Wua Nicolas Charlesb Jun Wanga Qingchen Wanga a State Key Laboratory of Lithospheric Evolution, Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, P.O. -

Extensional Tectonics in Convergent Margin Basins: an Example from the Salar De Atacama, Chilean Andes

Extensional tectonics in convergent margin basins: An example from the Salar de Atacama, Chilean Andes S. FLINT Department of Earth Sciences, University of Liverpool, P.O. Box 147, Liverpool L69 3BX, United Kingdom P TURNER 1 " r_T T _ „ > School of Earth Sciences, University of Birmingham, P.O. Bcoc 363, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom b. J. JUJLLifc/Y J A. J. HARTLEY Department of Geology & Petroleum Geology, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen AB9 2UE, United Kingdom ABSTRACT enance area for a 2-km-thick Oligocene conti- The modern Salar de Atacama basin nental basin-fill component (Paciencia Group). (Figs. 1 and 2) is situated in the Pre-Andean The Salar de Atacama basin of northern The Oligocene basin was an extensional to trans- Depression, bounded to the east by the Mio- Chile preserves stratigraphic evidence for the tensional basin. cene-Holocene Andean volcanic arc (High evolution of the Andean cycle. It has evolved The Miocene-Holocene Salar basin is a con- Andes) and to the west by thrusted Paleozo- from a non-arc-related rift, through back-arc tinental fore-arc basin. This latest segment of ic-Mesozoic sedimentary strata and Late Cre- and inter-are stages, to a Neogene fore-arc ba- the basin fill comprises pyroclastic and conti- taceous igneous intrusions of the Cordillera sin. Accumulation of the sedimentary succes- nental sedimentary rocks thrust over Quater- de Domeyko. The modern basin is —100 km sion was mainly due to extensional faulting. nary gravels in many places. The Cordillera de long (north-south) and 40 km wide; most of Important but short-duration contractional ep- la Sal is an intrabasinal uplift, initiated as a the surface is occupied by a saline playa com- isodes do link to known first-order plate-mar- thin-skinned contractional feature. -

Anatomy of Rifting: Tectonics and Magmatism in Continental Rifts, Oceanic Spreading Centers, and Transforms GEOSPHERE; V

Research Note THEMED DownloadedISSUE: Anatomy from of geosphere.gsapubs.org Rifting: Tectonics and Magmatism on January in 13, Continental 2016 Rifts, Oceanic Spreading Centers, and Transforms GEOSPHERE Introduction: Anatomy of rifting: Tectonics and magmatism in continental rifts, oceanic spreading centers, and transforms GEOSPHERE; v. 11, no. 5 Carolina Pagli1, Francesco Mazzarini2, Derek Keir3, Eleonora Rivalta4, and Tyrone O. Rooney5 1Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Università di Pisa, Via S. Maria 53, 56126 Pisa, Italy doi:10.1130/GES01082.1 2Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, Sezione di Pisa, Via della Faggiola 32, 56100, Pisa, Italy 3National Oceanography Centre Southampton, University of Southampton, Waterfront Campus, European Way, Southampton, Hampshire SO14 3ZH, UK 2 figures 4Helmholtz-Zentrum Potsdam Deutsches GeoForschungsZentrum (GFZ), Telegrafenberg, 14473 Potsdam, Germany 5Department of Geological Sciences, Michigan State University, 288 Farm Lane, East Lansing, Michigan 48824, USA CORRESPONDENCE: [email protected] ABSTRACT 2001). Magma intrusions thermally weaken the plate (Daniels et al., 2014), while CITATION: Pagli, C. Mazzarini, F., Keir, D., Rivalta, magma overpressure alters the stress field, facilitating extension at relatively E., and Rooney, T.O., 2015, Introduction: Anatomy of rifting: Tectonics and magmatism in continental Research at continental rifts, mid-ocean ridges, and transforms has shown low forces (Bialas et al., 2010). At most mid-ocean ridges, magma intrusions rifts, oceanic spreading centers, and transforms: that new plates are created by extensional tectonics, magma intrusion, and accommodate the majority of extension (Delaney et al., 1998; Sigmundsson, Geosphere, v. 11, no. 5, p. 1256–1261, doi: 10 .1130 volcanism. Studies of a wide variety of extensional processes ranging from 2006; Wright et al., 2012); however, mechanical faulting remains an important /GES01082.1. -

Principal Stresses

Chapter 4 Principal Stresses Anisotropic stress causes tectonic deformations. Tectonic stress is defined in an early part of this chapter, and natural examples of tectonic stresses are also presented. 4.1 Principal stresses and principal stress axes Because of symmetry (Eq. (3.32)), the stress tensor r has real eigenvalues and mutually perpendicu- lar eigenvectors. The eigenvalues are called the principal stresses of the stress. The principal stresses are numbered conventionally in descending order of magnitude, σ1 ≥ σ2 ≥ σ3, so that they are the maximum, intermediate and minimum principal stresses. Note that these principal stresses indicate the magnitudes of compressional stress. On the other hand, the three quantities S1 ≥ S2 ≥ S3 are the principal stresses of S, so that the quantities indicate the magnitudes of tensile stress. The orientations defined by the eigenvectors are called the principal axes of stress or simply stress axes, and the orientation corresponding to the principal stress, e.g., σ1 is called the σ1-axis (Fig. 4.1). Principal planes of stress are the planes parallel to two of the stress axes, or perpendicular to one of the stress axes. Deformation is driven by the anisotropic state of stress with a large difference of the principal stresses. Accordingly, the differential stress ΔS = S1 − S3, Δσ = σ1 − σ3 is defined to indicate the difference1. Taking the axes of the rectangular Cartesian coordinates O-123 parallel to the stress axes, a stress tensor is expressed by a diagonal matrix. Therefore, Cauchy’s stress (Eq. (3.10)) formula is ⎛ ⎞ ⎛ ⎞ ⎛ ⎞ t1(n) σ1 00 n1 ⎝ ⎠ ⎝ ⎠ ⎝ ⎠ t(n) = t2(n) = 0 σ2 0 n2 . -

A N–S-Trending Active Extensional Structure, the Fiuhut (Afyon) Graben

Turkish Journal of Earth Sciences (Turkish J. Earth Sci.), Vol. 16, 2007, pp. 391–416. Copyright ©TÜB‹TAK A N–S-trending Active Extensional Structure, the fiuhut (Afyon) Graben: Commencement Age of the Extensional Neotectonic Period in the Isparta Angle, SW Turkey AL‹ KOÇY‹⁄‹T & fiULE DEVEC‹ Middle East Technical University, Department of Geological Engineering, Active Tectonics and Earthquake Research Laboratory, TR–06531 Ankara, Turkey (E-mail: [email protected]) Abstract: The fiuhut graben is an 8–11-km-wide, 24-km-long, N–S-trending, active extensional structure located on the southern shoulder of the Akflehir-Afyon graben, near the apex of the outer Isparta Angle. The fiuhut graben developed on a pre-Upper Pliocene rock assemblage comprising pre-Jurassic metamorphic rocks, Jurassic–Lower Cretaceous platform carbonates, the Lower Miocene–Middle Pliocene Afyon stratovolcanic complex and a fluvio- lacustrine volcano-sedimentary sequence. The eastern margin of the fiuhut graben is dominated by the Afyon volcanics and their well-bedded fluvio- lacustrine sedimentary cover, which is folded into a series of NNE-trending anticlines and synclines. This volcano- sedimentary sequence was deformed during a phase of WNW–ESE contraction, and is overlain with angular unconformity by nearly horizontal Plio–Quaternary graben infill. Palaeostress analyses of slip-plane data recorded in the lowest unit of the modern graben infill and on the marginal active faults indicate that the fiuhut graben has been developing as a result of ENE–WSW extension since the latest Pliocene. The extensional neotectonic period in the Isparta Angle started in the latest Pliocene. All margins of the fiuhut graben are determined and controlled by a series of oblique-slip normal fault sets and isolated fault segments. -

Extentional Tectonics

Extensional Tectonics & Rift systems Where do normal faults occur? i.e. what plate boundaries? What are major sources of stress? (stress drives extension, compression, and transpression!) Extensional Tectonics & Rift systems Where do normal faults occur? i.e. what plate boundaries? • Mid-ocean ridges (divergent plate boundaries) • Continental rift (divergent plate boundaries) i.e. East African Rift, Basin and Range, U.S., à How else could we break up supercontinents! • Convergent plate boundaries i.e. Andes, Himalaya What are major sources of stress? (stress drives extension, compression, and transpression!) • Lithostatic load (vertical!) • Plate tectonics (horizontal) • Fluid pressure • Thermal effects • Buoyancy (vertical) Stress vs. A. B. Map View C. Strain http://earth.leeds.ac.uk/learnstructure/index.htm From: www.uoregon.edu/millerm/LVSS.html From: http://www.nygeo.org/foldedrock.jpg Refresher D. E. F. From: www.fault-analysis-group.ucd.ie From: structuralgeo.files.wordpress.com From: http://www.alexstrekeisen.it/english/meta/boudinage.php Stress Regime Compression Tension Shear Brittle Type of Strain Type Ductile A. B. Map View C. http://earth.leeds.ac.uk/learnstructure/index.htm From: www.uoregon.edu/millerm/LVSS.html From: http://www.nygeo.org/foldedrock.jpg D. E. F. From: www.fault-analysis-group.ucd.ie From: structuralgeo.files.wordpress.com From: http://www.alexstrekeisen.it/english/meta/boudinage.php Compression Tension Shear Reverse Fault Normal Fault Strike-Slip Fault Map View HW FW HW Brittle FW From: structuralgeo.files.wordpress.com -

Rifting, Seafloor Spreading, and Extensional Tectonics

2917-CH16.pdf 11/20/03 5:21 PM Page 382 CHAPTER SIXTEEN Rifting, Seafloor Spreading, and Extensional Tectonics 16.1 Introduction 382 16.6.2 Igneous-Rock Assemblage of Rifts 397 16.2 Cross-Sectional Structure of a Rift 385 16.6.3 Active Rift Topography 16.2.1 Normal Fault Systems 385 and Rift-Margin Uplifts 399 16.2.2 Pure-Shear versus Simple-Shear 16.7 Tectonics of Midocean Ridges 402 Models of Rifting 389 16.8 Passive Margins 405 16.2.3 Examples of Rift Structure 16.9 Causes of Rifting 408 in Cross Section 389 16.10 Closing Remarks 410 16.3 Cordilleran Metamorphic Core Complexes 390 Additional Reading 410 16.4 Formation of a Rift System 394 16.5 Controls on Rift Orientation 396 16.6 Rocks and Topographic Features of Rifts 397 16.6.1 Sedimentary-Rock Assemblages in Rifts 397 16.1 INTRODUCTION phere undergoes regional horizontal extension. A rift or rift system is a belt of continental lithosphere that Eastern Africa, when viewed from space, looks like it is currently undergoing extension, or underwent exten- has been slashed by a knife, for numerous ridges, sion in the past. During rifting, the lithosphere bounding deep, gash-like troughs, traverse the land- stretches with a component roughly perpendicular to scape from north to south (Figure 16.1a and b). This the trend of the rift; in an oblique rift, the stretching landscape comprises the East African Rift, a region direction is at an acute angle to the rift trend. where the continent of Africa is quite literally splitting Geologists distinguish between active and inactive apart—land lying on the east side of the rift moves rifts, based on the timing of the extension. -

Rift-Basin Structure and Its Influence on Sedimentary Systems

STRUCTURE AND SEDIMENTARY SYSTEMS 57 RIFT-BASIN STRUCTURE AND ITS INFLUENCE ON SEDIMENTARY SYSTEMS MARTHA OLIVER WITHJACK AND ROY W. SCHLISCHE Department of Geological Sciences, Rutgers University, Piscataway, New Jersey 08854-8066, U.S.A. e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] AND PAUL E. OLSEN Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, Palisades, New York 10964, U.S.A. e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: Rift basins are complex features defined by several large-scale structural components including faulted margins, the border faults of the faulted margins, the uplifted flanks of the faulted margins, hinged margins, deep troughs, surrounding platforms, and large- scale transfer zones. Moderate- to small-scale structures also develop within rift basins. These include: basement-involved and detached normal faults; strike-slip and reverse faults; and extensional fault-displacement, fault-propagation, forced, and fault-bend folds. Four factors strongly influence the structural styles of rift basins: the mechanical behavior of the prerift and synrift packages, the tectonic activity before rifting, the obliquity of rifting, and the tectonic activity after rifting. On the basis of these factors, we have defined a standard rift basin and four end-member variations. Most rift basins have attributes of the standard rift basin and/or one or more of the end-member variations. The standard rift basin is characterized by moderately to steeply dipping basement-involved normal faults that strike roughly perpendicular to the direction of maximum extension. Type 1 rift basins, with salt or thick shale in the prerift and/or synrift packages, are characterized by extensional forced folds above basement-involved normal faults and detached normal faults with associated fault-bend folds. -

Introduction to Structural Geology

Introduction to Structural Geology Patrice F. Rey CHAPTER 1 Introduction The Place of Structural Geology in Sciences Science is the search for knowledge about the Universe, its origin, its evolution, and how it works. Geology, one of the core science disciplines with physics, chemistry, and biology, is the search for knowledge about the Earth, how it formed, evolved, and how it works. Geology is often presented in the broader context of Geosciences; a grouping of disciplines specifically looking for knowledge about the interaction between Earth processes, Environment and Societies. Structural Geology, Tectonics and Geodynamics form a coherent and interdependent ensemble of sub-disciplines, the aim of which is the search for knowledge about how minerals, rocks and rock formations, and Earth systems (i.e., crust, lithosphere, asthenosphere ...) deform and via which processes. 1 Structural Geology In Geosciences. Structural Geology aims to characterise deformation structures (geometry), to character- ize flow paths followed by particles during deformation (kinematics), and to infer the direction and magnitude of the forces involved in driving deformation (dynamics). A field-based discipline, structural geology operates at scales ranging from 100 microns to 100 meters (i.e. grain to outcrop). Tectonics aims at unraveling the geological context in which deformation occurs. It involves the integration of structural geology data in maps, cross-sections and 3D block diagrams, as well as data from other Geoscience disciplines including sedimen- tology, petrology, geochronology, geochemistry and geophysics. Tectonics operates at scales ranging from 100 m to 1000 km, and focusses on processes such as continental rifting and basins formation, subduction, collisional processes and mountain building processes etc. -

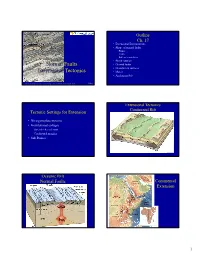

Normal Faults Extensional Tectonics

Geol341 Outline Ch. 17 • Extensional Environments • Shape of normal faults –Planar – Listric – Roll-over anticlines • Block rotation Normal Faults • Growth faults • Detachment surfaces Extensional Tectonics • Movie • Analog models Many diagrams are from Earth Structure, van der Pluijm and Marshak, 2004 2016 Extensional Tectonics Continental Rift Tectonic Settings for Extension • Divergent plate motions • Gravitational collapse – Over-thickened crust – Continental margins • Salt Domes Oceanic Rift Normal Faults Continental Extension 1 Extension in Convergent Margins Back Arcs Rifts Bounded by normal faults Van der Pluijm and Marshak (2004) Extension of the lithosphere 1 1300oC Van der Pluijm and Marshak (2004) Extension of the lithosphere 2 Consequences of Lithospheric Extension •Thinning of the lithosphere •Normal faulting at the surface •High heat flow (rinsing of the isotherms) 1300oC •Thermal subsidence during cooling after end of extension- > sedimentary basins Van der Pluijm and Marshak (2004) 2 North Sea Extensional Basin Evolution Norway Basin Depth to basement contour map Present Day North Sea Basin Scotland Fossen, 2010 3D view Gulfaks Field, North Sea Norway Structure of the base Cretaceous, east Viking graben, North Sea. (Fossen, 2010) Map view Gulfaks Pure shear vs. simple shear systems North Se Van der Pluijm and Marshak (2004) Fossen, 2010 3 Gravitational Collapse of Mt. Basin and Belts Range Province Weak Van der Pluijm and Marshak (2004) New Mountains-Active Fault –Basin and Range Province Deep seismic reflection data