The Impact of Cassava Growing in Luapula Valley, a Historical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zambia 30 September 2017

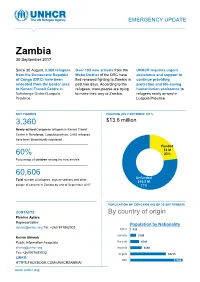

EMERGENCY UPDATE Zambia 30 September 2017 Since 30 August, 3,360 refugees Over 100 new arrivals from the UNHCR requires urgent from the Democratic Republic Moba District of the DRC have assistance and support to of Congo (DRC) have been fled renewed fighting to Zambia in continue providing relocated from the border area past two days. According to the protection and life-saving to Kenani Transit Centre in refugees, more people are trying humanitarian assistance to Nchelenge District/Luapula to make their way to Zambia. refugees newly arrived in Province. Luapula Province. KEY FIGURES FUNDING (AS 2 OCTOBER 2017) 3,360 $13.6 million requested for Zambia operation Newly-arrived Congolese refugees in Kenani Transit Centre in Nchelenge, Luapula province. 2,063 refugees have been biometrically registered Funded $3 M 60% 23% Percentage of children among the new arrivals Unfunded XX% 60,606 [Figure] M Unfunded Total number of refugees, asylum-seekers and other $10.5 M people of concern in Zambia by end of September 2017 77% POPULATION OF CONCERN (AS OF 30 SEPTEMBER) CONTACTS By country of origin Pierrine Aylara Representative Population by Nationality [email protected] Tel: +260 977862002 Other 415 Somalia 3199 Kelvin Shimoh Public Information Associate Burundi 4749 [email protected] Rwanda 6130 Tel: +260979585832 Angola 18715 LINKS: DRC 27398 HTTPS:FACEBOOK.COM/UNHCRZAMBIA/ www.unhcr.org 1 EMERGENCY UPDATE > Zambia / 30 September 2017 Emergency Response Luapula province, northern Zambia Since 30 August, over 3,000 asylum-seekers from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) have crossed into northern Zambia. New arrivals are reportedly fleeing insecurity and clashes between Congolese security forces FARDC and a local militia groups in towns of Pweto, Manono, Mitwaba (Haut Katanga Province) as well as in Moba and Kalemie (Tanganyika Province). -

DRAFT REPORT 2018 DA .Pdf

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF ZAMBIA REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT ASSURANCES FOR THE SECOND SESSION OF THE TWELFTH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY APPOINTED ON THURSDAY, 21ST SEPTEMBER, 2017 Printed by the National Assembly of Zambia i Table of Content 1.1 Functions of the Committee ........................................................................................... 1 1.2 Procedure adopted by the Committee .......................................................................... 1 1.3 Meetings of the Committee ............................................................................................ 2 PART I - CONSIDERATION OF SUBMISSIONS ON NEW ASSURANCES ............... 2 MINISTRY OF HIGHER EDUCATION ................................................................................ 2 11/17 Construction of FTJ Chiluba University .................................................................... 2 MINISTRY OF GENERAL EDUCATION ............................................................................. 3 39/17 Mateyo Kakumbi Primary School in Chitambo/Local Tour .................................. 3 21 /17 Mufumbwe Day Secondary School Laboratory ...................................................... 5 26/17 Pondo Basic School ....................................................................................................... 5 28/17 Deployment of Teachers to Nangoma Constituency ............................................... 6 19/16 Class Room Block at Lumimba Day Secondary School........................................... 6 17/17 Electrification -

Zambia 23 February 2018

INTER-AGENCY OPERATIONAL UPDATE Zambia 23 February 2018 Since September 2017, A combined total of 600 Five boreholes have 14,941 refugees have been children have been been drilled in registered at Kenani registered by Plan and Mantapala Refugee Transit Centre in Luapula Save the Children in Settlement by World Province. various categories of Vision International classes at the CFCs. KEY FIGURES 906 The Ministry of Health, with support from UN agencies and other partners, provides integrated health services at at Refugees have been relocated from Kenani to Kenani and Mantapala. © UNHCR/Bruce Mulenga.. Mantapala in five transfers 150 refugee families have built and moved in to their homes in Mantapala 76,000 Projected number of Congolese by 31 December 2018 ESTIMATEDFUNDING (ASTOTAL OF FEBRUINTER-ARYAGENCY 2018) FUNDING REQUIRED FOR THE CONGOLESE RESPONSE USDUSD 79,2 77,766,70066,700 M Total Inter-agency funding requested for the Congolese situation in Zambia Funded 6.559M Each head of the family at Kenani is given a plot to erect a shelter for the family. Above, a mother and her children Unfunded outside their home stead. UNHCR/Kelvin Shimoh 72.7M 1 INTER-AGENCY OPERATIONAL UPDATE > Zambia / 23 February 2018 Update on Achievements 76, 000 Projected number of Congolese by December 2018 Operational Context The protracted political stalemate in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), characterized by delays to hold presidential elections has spiraled into pockets of instability across parts of the country, notably the eastern region, where clashes between militia groups and government forces have continued unabated. Though a continuous stream of Congolese refugees have found international protection in Zambia for decades, the recent political instability has resulted in a humanitarian crisis that has led to an increased number of persons fleeing to neighboring countries, including Zambia. -

The Political Ecology of a Small-Scale Fishery, Mweru-Luapula, Zambia

Managing inequality: the political ecology of a small-scale fishery, Mweru-Luapula, Zambia Bram Verelst1 University of Ghent, Belgium 1. Introduction Many scholars assume that most small-scale inland fishery communities represent the poorest sections of rural societies (Béné 2003). This claim is often argued through what Béné calls the "old paradigm" on poverty in inland fisheries: poverty is associated with natural factors including the ecological effects of high catch rates and exploitation levels. The view of inland fishing communities as the "poorest of the poorest" does not imply directly that fishing automatically lead to poverty, but it is linked to the nature of many inland fishing areas as a common-pool resources (CPRs) (Gordon 2005). According to this paradigm, a common and open-access property resource is incapable of sustaining increasing exploitation levels caused by horizontal effects (e.g. population pressure) and vertical intensification (e.g. technological improvement) (Brox 1990 in Jul-Larsen et al. 2003; Kapasa, Malasha and Wilson 2005). The gradual exhaustion of fisheries due to "Malthusian" overfishing was identified by H. Scott Gordon (1954) and called the "tragedy of the commons" by Hardin (1968). This influential model explains that whenever individuals use a resource in common – without any form of regulation or restriction – this will inevitably lead to its environmental degradation. This link is exemplified by the prisoner's dilemma game where individual actors, by rationally following their self-interest, will eventually deplete a shared resource, which is ultimately against the interest of each actor involved (Haller and Merten 2008; Ostrom 1990). Summarized, the model argues that the open-access nature of a fisheries resource will unavoidably lead to its overexploitation (Kraan 2011). -

Full Text Document (Pdf)

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Macola, Giacomo (2006) “It Means as If We Are Excluded from the Good Freedom”: Thwarted Expectations of Independence in the Luapula Province of Zambia, 1964-1967. Journal of African History, 47 (1). pp. 43-56. ISSN 0021-8537. DOI https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021853705000848 Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/7559/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html ‘IT MEANS AS IF WE ARE EXCLUDED FROM THE GOOD FREEDOM’: THWARTED EXPECTATIONS OF INDEPENDENCE IN THE LUAPULA PROVINCE OF ZAMBIA, 1964-1966* BY GIACOMO MACOLA Centre of African Studies, University of Cambridge ABSTRACT: Based on a close reading of new archival material, this article makes a case for the adoption of an empirical, ‘sub-systemic’ approach to the study of nationalist and post- colonial politics in Zambia. -

TRIP REPORT: Zambia (September 14

TRIP REPORT: Zambia (September 14 - September 23, 1983) Dr. Hugh R. Taylor, M.D. Keith P. West, Jr., RD, MPH Prepared under Cooperative Agreement No. AID/DSAN-CA-0267 between the Dana Center, International Center for Epidemiologic and Preventive Ophthalmology ana the Office ot Nutrition, United States Agency for International Development. MIP REPORT: Zambia Table of Contents Page SUMMAR...... 1 INTRODUCTION .. 2 HOSPITAL AND RURAL HEALTH CENTER FINDINGS . .. .. .. .. .. 4 Ophthalmic Components of Visit to Zambia . ........ .. 4 VIRONENTAL OBSERVAIONS ................... 10 Fooc ana Dietary Habits. .................... 11 Sources of Water . 13 Housing Compounds. .. 14 VITAMIN A PREVEON PROGRAM IN ZAMBIA pRCOCL. 14 Plans tor Future Collaboration ....... .......... 17 Appendix A Sumlnary of Inpatient Cases of Measles for 1978, and ot PEM, Inflammatory Eye Diseases, and Measles for the Years 1980-1983. 19 Appendix B Attendees to the Luapula Valley Eye Disease Survey Work Session, Ndola, 21 September 198' . 20 Appendix C Memorandum: Luapula Valley Eye Disease Survey. 21 TRIREPORT: Zambia 14 - 23 September 1983 SUMMARY Vitamin A deficiency has long been implicated as a major cause of childhood blindness in Zambia, particularly in the Luapula Valley where blindness is known to be highly endemic. At the request of the National Food ana Nutrition Ccmmission, Government ot Zambia (GOZ), we visited the area ana reviewed the Government's draft proposal for the assessment and prevention of nutritional blindness in the Luapula Valley. During the visit we were impressed by the relatively large numbers of blind adults but the scarcity or very young children with active xerophthalmia or corneal scars. The WHO measles vaccination program and an apparent increase in the consumption or vitamin A-rich, small fish in the region may be important factors in what is perceived to be less blindness in recent years. -

2000 Census of Population and Housing

2000 Census of Population and Housing Published by Central Statistical Office, P. O. Box 31908, Lusaka, Luapula. Tel: 260-01-251377/253468 Fax: 260-01-253468 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.zamstats.gov.zm September, 2004 COPYRIGHT RESERVED Extracts may be published if Sources are duly acknowledged. Table of Content and Executive Summary i Table of Content and Executive Summary ii Preface The 2000 Census of Population and Housing was undertaken from 16th October to 15th November, 2000. This was the fourth census since Independence in 1964. The other three were carried out in 1969, 1980 and 1990. The 2000 Census operations were undertaken with the use of Grade 11 pupils as enumerators, Primary School Teachers as supervisors, Professionals from within Central Statistical Office and other government departments being as Trainers and Management Staff. Professionals and Technical Staff of the Central Statistical Office were assigned more technical and professional tasks. This report presents detailed analysis of issues on evaluation of coverage and content errors; population, size, growth and composition; ethnicity and languages; economic and education characteristics; fertility; mortality and disability. The success of the Census accrues to the dedicated support and involvement of a large number of institutions and individuals. My sincere thanks go to Co-operating partners namely the British Government, the Japanese Government, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the Norwegian Government, the Dutch Government, the Finnish Government, the Danish Government, the German Government, University of Michigan, the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) and the Canadian Government for providing financial, material and technical assistance which enabled the Central Statistical Office carry out the Census. -

REPORT of the AUDITOR GENERAL on the ACCOUNTS of the REPUBLIC for the Financial Year Ended 31St December 2019 Shorthorn Printers Ltd

Republic of Zambia REPORT of the AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE ACCOUNTS OF THE REPUBLIC for the Financial Year Ended 31st December 2019 Shorthorn Printers Ltd. REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA REPORT of the AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE ACCOUNTS OF THE REPUBLIC for the Financial Year Ended 31st December 2019 OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL VISION: A dynamic audit institution that promotes transparency, accountability, and prudent management of public resources. MISSION: To independently and objectively provide quality auditing services in order to assure our stakeholders that public resources are being used for national development and wellbeing of citizens. GOAL: To give assurance that at least 80% of public resources are applied towards developmental outcomes. CORE VALUES: Integrity Professionalism Objectivity Teamwork Confidentiality Excellence Innovation Respect PREFACE It is my honour and privilege to submit the Report of the Auditor General on the Accounts of the Republic of Zambia for the financial year ended 31st December 2019 in accordance with Article 212 of the Constitution, the Public Audit Act No.13 of 1994 and the Public Finance Management Act No.1 of 2018. The main function of my Office is to audit the accounts of Ministries, Provinces and Agencies (MPAs) and other institutions financed from public funds. In this regard, this report covers MPAs that appeared in the Estimates of Revenue and Expenditure for the financial year ended 31st December 2019 (Appropriation Act No. 22 of 2018). I conducted audits on the institutions to examine whether the funds appropriated by Parliament or raised by Government and disbursed had been accounted for. The audit was conducted in accordance with the International Standards of Supreme Audit Institutions (ISSAIs) which are the standards relevant for the audit of Public Sector entities. -

Environmental Awareness Among Key Actors of Selected Zambian Schools of Nchelenge District in Luapula Province

ENVIRONMENTAL AWARENESS AMONG KEY ACTORS OF SELECTED ZAMBIAN SCHOOLS OF NCHELENGE DISTRICT IN LUAPULA PROVINCE. By Makoba Charles A dissertation submitted to the University of Zambia in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Education in Environmental Education. The University of Zambia Lusaka 2014 i DECLARATION I, CHARLES MAKOBA, declare that the dissertation hereby submitted is my own work and it has not previously been submitted for any Degree, Diploma or other qualification at the University of Zambia or any other University. Signed: ………………………………………… Date:…………………………………………… ii APPROVAL This dissertation by Charles Makoba is approved as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the Master of Education (Environmental Education) degree of the University of Zambia. Signed……………………………………….. Date………………………………….. Signed……………………………………….. Date…………………………………... Signed……………………………………….. Date…………………………………… iii COPYRIGHT No part of this dissertation may be reproduced, restored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission. iv ABSTRACT There are several environmental conditions that have become areas of major concern at global, regional and national levels both in urban and rural areas. These conditions are as a result of environmental degradation such as deforestation, indiscriminate waste disposal, poor health and sanitation, water pollution and land degradation to mention but a few. Environmental mismanagement affects both human beings and other living organisms in different ways, such as outbreaks of diseases like cholera which is very common in Nchelenge district especially Kashikishi settlement and islands where it has become an annual event. Such diseases could be due to unfriendly environmental practices by the local people, who may probably, have very limited knowledge on how to utilize the environment in a more sustainable manner. -

THE EFFECTS of the ZAMBIA–ZAIRE BOUNDARY on the LUNDA and RELATED PEOPLES of the MWERU–LUAPULA REGION Author(S): M

THE EFFECTS OF THE ZAMBIA–ZAIRE BOUNDARY ON THE LUNDA AND RELATED PEOPLES OF THE MWERU–LUAPULA REGION Author(s): M. C. MUSAMBACHIME Source: Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria , DEC. 1984–JUNE 1985, Vol. 12, No. 3/4 (DEC. 1984–JUNE 1985), pp. 159-169 Published by: Historical Society of Nigeria Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44715375 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria This content downloaded from 72.195.177.31 on Sun, 30 May 2021 15:46:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria Vol. XII Nos. 3 &4 Dec. 1984-June 1985 THE EFFECTS OF THE ZAMBIA-ZAIRE BOUNDARY ON THE LUNDA AND RELATED PEOPLES OF THE MWERU- LUAPULA REGION: by M. C. MUSAMBACHIME, Dept. of History , University of Zambia, Lusaka. The area designated as Mweru- Luapula stretches from the Calwe to the Mambiliam rapids (formerly called Jonston Falls), covering the banks of the lower Luapula River and the shores of Lake Mweru. On the west is a wide swampy plain with a number of habitable high lands. -

How Would You Rate Government's

PMRC, sparking policy discussion and debate on Adapted On September 23rd Government released an official statement highlighting its development by: Government delivery after 2 years in office. achievements after two years in office. PMRC has graphically illustrated this statement and asks YOU the reader to rate the Zambian Governments’ delivery. HOW WOULD YOU RATE GOVERNMENT’S PERFORMANCE? ARE THEY DELIVERING? HEALTH EDUCATION EDUCATION DEVELOPMENT AGRICULTURE K3.6 Billion K5.6 Billion K393.3 From the Education allocation, AGRICULTURE MILLION K393.3 million is being spent on Allocated on health Representing the development of secondary DEVELOPMENT representing 11.3% 15.8% increase school infrastructure across the of the budget. over the 2012 country. 900 900 extension officers were recruited for the budget, is being RECRUITED purpose of crop diversification. spent in 2013 for 35 new secondary schools to the provision of be constructed across Zambia. The revamping of the Nitrogen Chemicals of 70,727 Zambia has produced 70,727 metric tonnes of quality education 35 (9 Secondary Schools are being METRIC TONS SECONDARY D compound fertilizer, which is currently being and skills training SCHOOLS constructed). for children and distributed to farmers across the country. youths. From 2011 to 2013, 19,700 teachers 19,700 have been employed and deployed. HOUSING AND TEACHERS DEPLOYED WATER AND MAP KEY US$475.1 K475.1 million is being spent COMMUNITY AMENITIES SANITATION SERVICES MILLION on the rehabilitation of existing HEALTH SERVICES HEALTH CENTRES District trades training institutions in all GOVERNMENT SOURCED Hospitals provinces and creation of new 2,500 2,500 boreholes being drilled ones in selected districts. -

Republic of Zambia Report of the Public Accounts

REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA REPORT OF THE PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE ON THE REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE ACCOUNTS OF THE REPUBLIC FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR ENDED 31ST DECEMBER, 2015 FOR THE FIRST SESSION OF THE TWELFTH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY Appointed by the Resolution of the House on 10th October, 2016 Printed by the National Assembly of Zambia REPORT OF THE PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE ON THE REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE ACCOUNTS OF THE REPUBLIC FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR ENDED 31ST DECEMBER, 2015 FOR THE FIRST SESSION OF THE TWELFTH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY Appointed by the Resolution of the House on 10th October, 2016 REPORT OF THE PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE ON THE REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE ACCOUNTS OF THE REPUBLIC FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR ENDED 31ST DECEMBER, 2015 FOR THE FIRST SESSION OF THE TWELFTH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY, APPOINTED BY RESOLUTION OF THE HOUSE ON 10TH OCTOBER, 2016 Consisting of: Mr H Kunda, MP (Chairperson); Mr A Chiteme, MP; Mr M Mbulakulima, MP; Mr C Mweetwa, MP; Mr T J Kasonso, MP; Mr M C Munkonge, MP; Mrs D Mwape, MP; Mr K Simbao, MP; Ms B M Tambatamba, MP The Honourable Mr Speaker National Assembly Parliament Buildings LUSAKA Sir, Your Committee has the honour to present its Report on the Report of the Auditor General on the Accounts of the Republic for the Financial Year ended 31st December, 2015. 1 Functions of Your Committee 2. The functions of your Committee are to examine the accounts showing the appropriation of sums granted by the National Assembly to meet the public expenditure, the Report of the Auditor General on these accounts and such other accounts, and to exercise the powers as provided for under Article 203(5) and (6) of the Constitution of the Republic of Zambia, Act No.