El Incremento De La Religiosidad En China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Chinese Bible

The Chinese Bible ChinaSource Quarterly Autumn 2018, Vol. 20, No. 3 Thomas H. Hahn Docu-Images In this issue . Editorial An In-depth Look at the Chinese Bible Page 2 Joann Pittman, Guest Editor Articles A Century Later, Still Dominant Page 3 Kevin XiYi Yao The Chinese Union Version of the Bible, published in 1919, remains the most dominant and popular translation used in China today. The author gives several explanations for its enduring acceptance. The Origins of the Chinese Union Version Bible Page 5 Mark A. Strand How did the Chinese Union Version of the Bible come into being? What individuals and teams did the translation work and what sources did they use? Strand provides history along with lessons that can be learned from years of labor. Word Choice Challenges Page 8 Mark A. Strand Translation is complex, and the words chosen to communicate concepts are crucial; they can significantly influence the understand- ing of the reader. Strand gives examples of how translators struggle with this aspect of their work. Can the Chinese Union Version Be Replaced in China? Page 9 Ben Hu A Chinese lay leader gives his thoughts on the positives and negatives of using just the CUV and the impact of using other transla- tions. Chinese Bible Translation by the Catholic Church: History, Development and Reception Page 11 Monica Romano Translation of scripture portions by Catholics began over 700 years ago; however, it was not until 1968 that the entire Bible in Chi- nese in one volume was published. The author follows this process across the centuries. -

Religious Revival and Exit from Religion in Contemporary China

China Perspectives 2009/4 | 2009 Religious Reconfigurations in the People’s Republic of China Religious Revival and Exit from Religion in Contemporary China Benoît Vermander Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/4917 DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.4917 ISSN : 1996-4617 Éditeur Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Édition imprimée Date de publication : 31 décembre 2009 ISSN : 2070-3449 Référence électronique Benoît Vermander, « Religious Revival and Exit from Religion in Contemporary China », China Perspectives [En ligne], 2009/4 | 2009, mis en ligne le 01 décembre 2012, consulté le 28 octobre 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/4917 ; DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.4917 © All rights reserved Special Feature s e v Religious Revival and Exit i a t c n i e from Religion in h p s c r Contemporary China e p BENOÎT VERMANDER This paper examines both the revival of religious organisations and practices in China and what could be coined the “exit from religion” exemplified by the loss of religious basis for social togetherness and the instrumentalisation of religious organisations and discourse. It argues that “revival” and “exit” taken as a twofold phenomenon facilitate an understanding of the evolving and often disputed nature of China’s religious sphere throughout history as well as the socio-political stage that the country is entering. he study of religion in the Chinese context confronts between civil society and the party-state whose policies and some basic problems: how relevant is the term “reli - instructions it transmits. (4) Further, the State Administration T gion,” borrowed from Western languages via Japan - of Religious Affairs (5) at the central, provincial, and local lev - ese, in referring to the social forms examined? (1) Even if one els functions as a sort of “ministry of religion” with extensive chooses to speak of a “religious sphere,” can Western con - powers. -

H-Diplo Roundtable XXI-38 on Kosicki. Catholics on the Barricades: Poland, France, and “Revolution,” 1891-1956

H-Diplo H-Diplo Roundtable XXI-38 on Kosicki. Catholics on the Barricades: Poland, France, and “Revolution,” 1891-1956. Discussion published by George Fujii on Monday, April 27, 2020 H-Diplo Roundtable XXI-38 Piotr H. Kosicki. Catholics on the Barricades: Poland, France, and “Revolution,” 1891-1956. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018. ISBN: 9780300225518 (hardcover, $40.00). 27 April 2020 | https://hdiplo.org/to/RT21-38 Roundtable Editor: Diane Labrosse | Production Editor: George Fujii Contents Introduction by Sarah Shortall, University of Notre Dame.. 2 Review by Natalie Gasparowicz, Duke University.. 5 Review by Rachel Johnston-White, University of Groningen.. 8 Review by Albert Wu, American University of Paris. 13 Response by Piotr H. Kosicki, University of Maryland.. 17 Introduction by Sarah Shortall, University of Notre Dame Piotr Kosicki’s Catholics on the Barricades is a testament to the exciting new wave of scholarship on the history of Catholicism that has emerged in the past few years. Led by a new generation of scholars, it has drawn attention to the pivotal role that Catholics have played in the signal developments of twentieth-century politics, from the rise of fascism and Communism to decolonization and human rights activism.[1] Together, these works have helped to reframe our understanding of twentieth-century diplomatic and international history, as the H-Diplo roundtables dedicated to several of these works attest.[2] The bulk of this recent scholarship has focused on Western Europe, where the rise of conservative Christian Democratic parties was the dominant feature of postwar political life.[3] The great merit of Kosicki’s book is to draw our attention to a very different strand in the postwar history of European Catholicism: the rise of a transnational Catholic engagement with socialism that managed to bridge the formidable divide of the Iron Curtain. -

People, Communities, and the Catholic Church in China Edited by Cindy Yik-Yi Chu Paul P

CHRISTIANITY IN MODERN CHINA People, Communities, and the Catholic Church in China Edited by Cindy Yik-yi Chu Paul P. Mariani Christianity in Modern China Series Editor Cindy Yik-yi Chu Department of History Hong Kong Baptist University Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong This series addresses Christianity in China from the time of the late Ming and early Qing dynasties to the present. It includes a number of disciplines—history, political science, theology, religious studies, gen- der studies and sociology. Not only is the series inter-disciplinary, it also encourages inter-religious dialogue. It covers the presence of the Catholic Church, the Protestant Churches and the Orthodox Church in China. While Chinese Protestant Churches have attracted much scholarly and journalistic attention, there is much unknown about the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church in China. There is an enor- mous demand for monographs on the Chinese Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church. This series captures the breathtaking phenomenon of the rapid expansion of Chinese Christianity on the one hand, and the long awaited need to reveal the reality and the development of Chinese Catholicism and the Orthodox religion on the other. Christianity in China refects on the tremendous importance of Chinese-foreign relations. The series touches on many levels of research—the life of a single Christian in a village, a city parish, the conficts between converts in a province, the policy of the provincial authority and state-to-state relations. It concerns the infuence of dif- ferent cultures on Chinese soil—the American, the French, the Italian, the Portuguese and so on. -

News Update on Religion and Church in China March 23 – June 28, 2016

News Update on Religion and Church in China March 23 – June 28, 2016 Compiled by Katharina Wenzel-Teuber Translated by David Streit e “News Update on Religion and Church in China” appears regularly in each issue of Religions & Chris- tianity in Today’s China (RCTC). Since the editorial sta learns of some items only later, it can happen that there are chronological overlaps between “News Updates” of two consecutive issues of RCTC. In these cases stories referred to in earlier “News Updates” will not be repeated. All “News Updates” can be found online at the website of the China-Zentrum (www.china-zentrum.de). – e last “News Update” (RCTC 2016, No. 2, pp. 3-19) covered the period November 10, 2015 – March 24, 2016. March 23, 2016: 90 year old bishop of Wenzhou steps back from active leadership, but may not resign Bishop Vincent Zhu Weifang, who belongs to the ocial part of the Diocese of Wenzhou, has declared to his priests that he is stepping back from front line leadership due to his advanced age, and has instead named Fr. Ma Xianshi administrator of the diocese. As UCAN has explained, Bishop Zhu cannot resign outright from his post as bishop, since his coadjutor bishop with the right of succession, Bishop Peter Shao Zhumin, who heads the “underground” section of the Diocese of Wenzhou (around two-thirds of the 120,000 faithful), is not recognized by the government. UCAN reports that the government, before ocially recognizing any bishop of the underground Church, demands that they rst concelebrate a Mass with an illicit bishop who was ordained without papal mandate and also join the Catholic Patri- otic Association (UCAN April 11). -

Religions & Christianity in Today's

Religions & Christianity in Today's China Vol. II 2012 No. 2 Contents Editorial | 2 News Update on Religion and Church in China December 2011 to March 2012 | 3 Compiled by Katharina Feith, Jan Kwee, Anton Weber, Martin Welling, and Katharina Wenzel-Teuber The Chinese Church’s Response to Migration within Mainland China (Part II) | 20 John B. Zhang The Kingdom and Power: Elements of Growth in Chinese Christianity Some Personal Insights | 38 Sigurd Kaiser Imprint – Legal Notice | 50 Religions & Christianity in Today's China, Vol. II, 2012, No. 2 1 Editorial Today we can present to our readers the second 2012 issue of Religions & Christianity in Today’s China (中国宗教评论). As in previous issues, it includes the regular series of News Updates which give an insight into recent events and general trends with regard to religions and especially Christianity in today’s China. This number, furthermore, continues with Part II of the article “The Chinese Church’s Response to Migration within Mainland China” by John B. Zhang. The main focus of this article is on Catholic expatriates in China. The pastoral services offered to German and South Korean Catholics, as well as those available to other expatriate Catholic commu nities in Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, and other cities, are closely studied in this contribu tion. The third article entitled “The Kingdom and Power: Elements of Growth in Chinese Christianity. Some Personal Insights” by Sigurd Kaiser shows that there are various el ements of Protestant church growth which exhibit a strong biblical orientation as, e.g., the importance of praying, witness and physical healing, its character as a lay movement, and a new attitude to western culture. -

Press Release – January 10, 2011

NEWS RELEASE – March 16, 2014 The Cardinal Kung Foundation Contact: Joseph Kung, PO Box 8086, Stamford, CT 06905, U.S.A. Tel: 203-329-9712 Fax: 203-329-8415 E-Mail: [email protected] Web Site: http://www.cardinalkungfoundation.org Bishop Joseph FAN ZhongLiang, S.J., Bishop of Shanghai, has died Bishop Joseph FAN ZhongLiang, S.J., the underground Bishop of Shanghai appointed by Blessed Pope John Paul II, died today at 5:58 pm Shanghai surrounded by some of his faithful parishioners. He was 97 year old. The Cardinal Kung Foundation has learned that Bishop Fan suffered from a high fever several days before he died. He died at his home still under house arrest, a sentence that entailed strict surveillance by the government for most of the last two decades. The funeral arrangements for Bishop Fan has not been finalized, but will be limited for only two days as dictated by the government. Upon his death, an underground priest immediately offered a Mass for the repose of the soul of Bishop Fan in Bishop's own apartment. Shortly after the completion of the Mass, which was attended by a few underground Catholics, several Shanghai government officials arrived as the result of their surveillance. They ordered the immediate transfer of the body of Bishop Fan to a funeral home. As more than 2,000 underground Catholics are expected to attend the Funeral Mass of their beloved Bishop Fan, the underground church made a request to the government that the funeral Mass be held at St. Ignatius Cathedral which has the capacity to hold over 2000 worshipers. -

“Religion in China Today: Resurgence and Challenge” November 3, 2014 | Village West 15Th Floor, Room A, UC San Diego

School of International Relations and Paci c Studies “Religion in China Today: Resurgence and Challenge” November 3, 2014 | Village West 15th Floor, Room A, UC San Diego Over the past three decades, there has been a remarkable resurgence of religious belief and practice in China. This has taken many forms, from the revival and transformation of folk religion, the reinvigoration of Christianity, Buddhism and Islam, and even the creation of new religious movements. These developments present new challenges to the Chinese state and have led to global controversies over the government’s handling of these challenges. This conference will bring together distin- guished Chinese and American scholars for a dialogue about the causes and political consequences of these developments. This will be a full-day workshop comprised of three panels and one roundtable discussion. Each speaker will pre- pare 15-20 minute remarks on their chosen topic, will join the discussion after all the panelists finish presentations, and will field questions from the audience. Workshop audience include faculty, students and community members. Agenda Monday, November 3, 2014 | Village West 15th Floor, Room A, UC San Diego 8:00 - 8:15 am Light Breakfast 8:15 - 8:20 am Welcome Remarks by Richard Madsen, Director of Fudan-UC Center on Contemporary China 8:20 - 9:50 am I. Christianity in China: Developments and Tensions Moderator: Richard Madsen, UC San Diego “The Catholic Church in Contemporary Shanghai” Paul Mariani, Santa Clara University “Party-State - Protestant Church Relations in Contemporary China: A Public Transcript Perspective” Carsten Vala, Loyola University of Maryland “Understanding Christianity in Contemporary China” Edward Xu, Fudan University 9:50 - 10:05 am Coffee Break 10:05 - 11:25 am II. -

China's Satellite Spots Possible Plane Debris

SUNDAY, MARCH 23, 2014 INTERNATIONAL Thousands mourn Shanghai’s ‘underground’ Bishop SHANGHAI: Thousands of mourn- Fan Zhongliang, whose faith led who was imprisoned for much of after several days of high fever, gy in red-and-white robes. A large the most prominent converts ers packed a Shanghai square yes- him to endure decades of suffer- the last two decades and spent his according to the US-based photo of Fan adorned the hall, secured by 16th-century Italian mis- terday to bid farewell to “under- ing at the hands of China’s ruling final years under house arrest, Cardinal Kung Foundation, a surrounded by flowers. Chinese sionary Matteo Ricci. The long-serv- ground” Catholic Bishop Joseph Communist Party, they said. Fan, died last Sunday at the age of 97 Roman Catholic organization. authorities had turned down a ing bishop of Shanghai’s state-run China has a state-controlled request from worshippers to hold Catholic Church, Aloysius Jin Luxian, Catholic Church, which rejects the Fan’s funeral service at Shanghai’s died last year at age 96. Father Vatican’s authority, as well as an main Catholic cathedral, the Giuseppe Zhu Yude, a priest from “underground” church. Experts esti- Cardinal Kung Foundation said. the underground church, led the mate that there are as many as 12 mass for Fan’s funeral yesterday. million Catholics in China, split ‘Forbidden’ from duty Overseas and underground Chinese roughly evenly between the two Fan was ordained a priest in Catholics had requested that Jin’s churches. “I came here to bid 1951 and spent more than two successor, Thaddeus Ma Daqin, be farewell to our bishop,” said a decades in jail and labor camps. -

Vatican Insider March 17, 2014

NEWS REPORT from Vatican Insider The president of Bishops' Conference of China's 'underground' Catholic Vatican Insider March 17, 2014 by Gerard O'Connell Bishop Joseph Fan Zhongliang of Shanghai, 96,the President of the Bishops' Conference of the 'underground' Catholic community in China, and head of the local underground community in that Chinese metropolis, died on Sunday, March 16, after a long illness. The local authorities in Shanghai have granted the Catholic faithful two days to pay their final respects to the late Jesuit bishop. It seems this agreement was reached after an uncertain early reaction in which officials removed his biretta, an act that was meant to underline the fact that they do not recognize him as a bishop, a Church source told UCA News, the main Catholic news agency in Asia. The Cardinal Kung Foundation – Press Release March 17, 2014 Vatican Insider Page 1 "They backed off as a result of a protest by the underground Church administrator, who threatened not to hold a Mass and let the officials face the resulting wrath of angry Catholics," the source said. The Bishop's body is likely to be cremated, a Church source told Vatican Insider, as that is a common practice there. This happened to the body of the other Jesuit bishop from Shanghai, Aloysius Jin Luxian, who died on 27 April 2013. Bishop Fan was born in 1918 and baptized at the age of 14. He entered the Shanghai Jesuit novitiate on 30 August 1938 together with Jin Luxian, though Fan was two years younger, and for the next 17 years they journeyed together. -

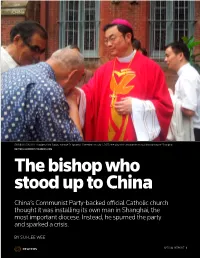

The Bishop Who Stood up to China China’S Communist Party-Backed Official Catholic Church Thought It Was Installing Its Own Man in Shanghai, the Most Important Diocese

CHINA ORDINATION DAY: Thaddeus Ma Daqin, outside St. Ignatius Cathedral on July 7, 2012, the day of his ordination as auxiliary bishop of Shanghai. REUTERS/HANDOUT/UCANEWS.COM The bishop who stood up to China China’s Communist Party-backed official Catholic church thought it was installing its own man in Shanghai, the most important diocese. Instead, he spurned the party and sparked a crisis. BY SUI-LEE WEE SPECIAL REPORT 1 BISHOP WHO STOOD UP TO CHINA SHANGHAI, APRIL 1, 2014 t was shaping as a win in the Communist Party’s quest to contain a longtime Inemesis, the Roman Catholic Church. In July 2012, a priest named Thaddeus Ma Daqin was to be ordained auxiliary bishop of Shanghai. The Communist body that has governed the church for six decades had angered the Holy See by ap- pointing bishops without Vatican approval. Known as the Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association, it was now about to install Ma, one of its own officials, as deputy in China’s largest Catholic diocese. “The anticipation was he would be a yes man,” says Jim Mulroney, a priest and editor of the Hong Kong-based Sunday Examiner, a Catholic newspaper. Instead, standing before a thousand CONFINEMENT: Thaddeus Ma has been confined to the Sheshan monastery on a mountain outside Catholics and government officials at Saint Shanghai since repudiating the official church in July 2012. REUTERS/ ALY SONG Ignatius Cathedral, Ma spurned the party: It wouldn’t be “convenient” for him to re- main in the Patriotic Association, he said. The anticipation was he from Beijing pass messages to the Vatican Many in the crowd erupted into thun- would be a yes man. -

The Denver Catholic Register

The Denver Catholic Register JANUARY 18, 1989 VOL LXV NO. 2 Colorado’s Largest Weekly 20 PAGES 2S CENTS This the first of a two-part series on Sat anism and its effects on young people and how parents, teachers and other adults can deal with'the problem. By Christine Capra-Kramer Register Staff "Dower. “^-In the dark world of Satanism, power is the greatest motivator. Both adults and ado lescents who become involved with worship ing Satan, do so in part because they lust for power in their lives, a power they believe Satan provides. “Satanism seems to meet a lot of kids’ needs that are central to the adolescent experience,” according to Cindy Clark, an expert on ado lescent deviant behavior. “For instance, a sense of belonging, a sense of peer networking, recog nition and self-esteem. Continued on page 4 Healing service e church Loretto Heights attracts 2,500 in China - Part 2 sale controversy. PAGE 3 PAGE 6 PAGE 11 Page 2 - January 18, 1989 - Denver Catholic Register As the Congress returns, so do the controversies By Liz Schevtchuk WASHINGTON (NC) — Congresses come and go. but issues often linger — giving the incoming 101st WASHINGTON Z (.'ongress ample opportunity to not only delve into new business but to revisit some old controversies. LETTER Likely to demand congressional attention again arc — to name a few — domestic issues of housing, day church and women’s groups and heated opposition care and parental leave, rural development, the from interest groups before dying in the 100th Con fairness of the death penalty, and the minimum gress.