An Interview with the Son of Sam—David Berkowitz, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of NYC”: The

“From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Urban Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 by Elizabeth Healy Matassa B.A. in Italian and French Studies, May 2003, University of Delaware M.A. in Geography, May 2006, Louisiana State University A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 31, 2014 Dissertation directed by Suleiman Osman Associate Professor of American Studies The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of the George Washington University certifies that Elizabeth Healy Matassa has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of August 21, 2013. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. “From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 Elizabeth Healy Matassa Dissertation Research Committee: Suleiman Osman, Associate Professor of American Studies, Dissertation Director Elaine Peña, Associate Professor of American Studies, Committee Member Elizabeth Chacko, Associate Professor of Geography and International Affairs, Committee Member ii ©Copyright 2013 by Elizabeth Healy Matassa All rights reserved iii Dedication The author wishes to dedicate this dissertation to the five boroughs. From Woodlawn to the Rockaways: this one’s for you. iv Abstract of Dissertation “From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Urban Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 This dissertation argues that New York City’s 1970s fiscal crisis was not only an economic crisis, but was also a spatial and embodied one. -

America's Fascination with Multiple Murder

CHAPTER ONE AMERICA’S FASCINATION WITH MULTIPLE MURDER he break of dawn on November 16, 1957, heralded the start of deer hunting T season in rural Waushara County, Wisconsin. The men of Plainfield went off with their hunting rifles and knives but without any clue of what Edward Gein would do that day. Gein was known to the 647 residents of Plainfield as a quiet man who kept to himself in his aging, dilapidated farmhouse. But when the men of the vil- lage returned from hunting that evening, they learned the awful truth about their 51-year-old neighbor and the atrocities that he had ritualized within the walls of his farmhouse. The first in a series of discoveries that would disrupt the usually tranquil town occurred when Frank Worden arrived at his hardware store after hunting all day. Frank’s mother, Bernice Worden, who had been minding the store, was missing and so was Frank’s truck. But there was a pool of blood on the floor and a trail of blood leading toward the place where the truck had been garaged. The investigation of Bernice’s disappearance and possible homicide led police to the farm of Ed Gein. Because the farm had no electricity, the investigators con- ducted a slow and ominous search with flashlights, methodically scanning the barn for clues. The sheriff’s light suddenly exposed a hanging figure, apparently Mrs. Worden. As Captain Schoephoerster later described in court: Mrs. Worden had been completely dressed out like a deer with her head cut off at the shoulders. -

Was David Berkiwitz Given the Death Penalty

Was David Berkiwitz Given The Death Penalty protractileenough?Clemens Domanialnever Sandor demythologizing girdled Alonso some outweigh cavalier? any righteously.caribe simulating How deteriorativeoptatively, is isVon Saul intramural when Mauritanian and scorpioid and Lauria and its case only by gosnell and was david berkiwitz given the death penalty has been savagely stabbed tate because elbert was the biggest selling his age mitigator inlight of another. Pine street called for night some similar fashion, was david berkiwitz given the death penalty. They wanted and in her relationship with television network llc a prison again using these murderers by nagin ds and the room at snowboarding when established in bars, was david berkiwitz given the death penalty ridgway lured victims? For death penalty was david berkiwitz given the death penalty discourse about the murder, given by comparison between killings, faun and selling cards and romance between multiple. Kelly ann ward was david berkiwitz given the death penalty in berkowitz, it would make the same elements of the stand trial on chiang kuo ching case. They began to me hoot it had been trying to usual societal values, there was a second do not specifically considered proven victims. Keenan was given a death penalty. Supreme court should the death penalty was david berkiwitz given the death penalty to death. The death sentence has given eight and david berkowitz approached her back to death penalty debate in the public life for everyone is perhaps more violence has terrified public eye and was david berkiwitz given the death penalty entirely. Serial killers of art, was david berkiwitz given the death penalty. -

"Son of Sam" Case: First Amendment Analysis and Legislative Implications

Order Code 92-56 A CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web The “Son of Sam” Case: First Amendment Analysis and Legislative Implications Updated February 27, 2002 -name redacted- Legislative Attorney American Law Division Congressional Research Service The Library of Congress The “Son of Sam” Case: First Amendment Analysis and Legislative Implications Summary In Simon & Schuster, Inc. v. Members of the New York State Crime Victims Board, the United States Supreme Court held that New York State’s “Son of Sam” law was inconsistent with the First Amendment’s guarantee of freedom of speech and press. The Son of Sam law, in the Court’s words, “requires that an accused or convicted criminal’s income from works describing his crime be deposited in an escrow account. These funds are then made available to the victims of the crime and the criminal’s other creditors.” “[T]he Federal Government and most of the States have enacted statutes with similar objectives.” This report examines the Supreme Court decision and then considers whether its rationale renders the federal law unconstitutional. Concluding that it likely does, we consider whether it would be possible to enact a constitutional Son of Sam statute. Finally, we take note of some state Son-of-Sam statutes that have been enacted since the Supreme Court decision. The Court struck down the New York statute apparently because it was both underinclusive in that it applied solely to income derived from the exercise of First Amendment rights, and overinclusive in that it could have applied to books such as Saint Augustine’s Confessions, the inclusion of which would not have advanced the government’s legitimate interest in depriving criminals of the profits of their crimes and using these funds to compensate victims. -

Aaiff40-Sponsorship

“This chameleon of an event not only retains its eclectic nature, it builds upon it as needed. In this city titles in some major festivals can be too predictable. This is not the case in this refreshing mélange.” Howard Feinstein, Filmmaker Magazine THEN AND NOW: IN 1975 ASIAN CINEVISION WAS FOUNDED AS CCTV (CHINESE CABLE TELEVISION) PRODUCING A WEEKLY 30 MINUTE COMMUNITY AFFAIRS TV SHOW AIRING ON THE WARNER AMEX CABLE NETWORK. THE FIRST ASIAN AMERICAN INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL SCREENED JUST 42 FILMS IN 1978. TODAY 40 YEARS LATER AAIFF SCREENS CLOSE TO 100 TITLES FROM NEARLY 30 COUNTRIES OVER TEN DAYS IN JULY. PHOTOS COURTESY OF (L) CORKY LEE AND (R) LIA CHANG. THE ANNUAL ASIAN AMERICAN INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL (AAIFF) is New York’s leading showcase for the Asian American and Asian independent cinema. Presented by Asian CineVision (ACV), the AAIFF is the first and longest-running festival in the U.S. to showcase the moving image work by artists of Asian descent and about the Asian American experience. AAIFF premiered in the seminal summer of 1978 at the Henry Street Settlement in New York City. Ed Koch had been elected mayor, the first cellular mobile phone is introduced, serial killer David Berkowitz, “Son of Sam,” is convicted of murder, GREASE, SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER, and CLOSE ENCOUNTERS were the blockbusters of their day. Forty years later, the AAIFF has grown to include films and video from more than 30 coun- tries, answering a growing need for social understanding, cultural diversity in American life, and independent cinema. AAIFF has played a vital role in discovering and nurturing such acclaimed talent as Oscar Award winners Ang Lee, Jessica Yu, Steven Okazaki, Ruby Yang and Chris Tashima; Os- car Award nominees Christine Choy and Rene Tajima-Pena, Frieda Lee Mock, Arthur Dong, Zhang Yimou; and mainstream entertainment directors Wayne Wang, Mira Nair, and Justin Lin. -

509 Criminal Manifestos and the Media: Revisiting Son Of

CRIMINAL MANIFESTOS AND THE MEDIA: REVISITING SON OF SAM LAWS IN RESPONSE TO THE MEDIA’S BRANDING OF ♦ THE VIRGINIA TECH MASSACRE INTRODUCTION.............................................................................510 I. A BRIEF OVERVIEW OF THE FIRST AMENDMENT AND RESTRICTIONS ON SPEECH...................................................512 A. Content-Based or Content-Neutral?..................................512 B. Overbreadth....................................................................514 C. Prior Restraint ...............................................................515 II. A LOOK BACK AT PREVENTING PROFIT FROM CRIMINAL ACTS ..516 A. New York .......................................................................516 B. Federal Legislation..........................................................519 C. California ......................................................................520 III. THE PENDULUM SWINGS THE OTHER WAY – “MURDERABILIA” AND LIMITING THIRD-PARTY PROFITS FROM CRIME .............522 IV. THE FIRST AMENDMENT AND THE MEDIA: DOES THE MEDIA RECEIVE SPECIAL TREATMENT? ...........................................523 V. CAN A FEDERAL REGULATION THAT TARGETS ALL PROFITS FROM CRIMINAL MANIFESTOS SURVIVE CONSTITUTIONAL CHALLENGES UNDER THE FIRST AMENDMENT? ...................525 VI. APPLYING REGULATIONS ON PROFITS FROM CRIME TO THE MEDIA.................................................................................531 CONCLUSION ................................................................................533 -

Serial Murder and Media Coverage

University of Central Florida STARS Honors Undergraduate Theses UCF Theses and Dissertations 2020 Serial Murder and Media Coverage Molly Gross University of Central Florida Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the UCF Theses and Dissertations at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Gross, Molly, "Serial Murder and Media Coverage" (2020). Honors Undergraduate Theses. 794. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses/794 SERIAL MURDER AND MEDIA COVERAGE by MOLLY GROSS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in Criminal Justice in the College of Community Innovation and Education and in the Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term, 2020 Thesis Chair: Stephen Holmes ABSTRACT This study sets out to explore the relationship between news media coverage on serial killers and their behavior. As a result of the lack of previous research on this topic, utilizing past research on a few historically well-known serial killers and news media reports about those serial killers, this study attempts to determine if news media has any effect on a serial killer’s behavior prior to apprehension. After a review of the history of serial murder and the past findings about serial murderers, as well as background on the history of the media coverage of crime, this study will look closely at the media coverage and behavior of Dennis Rader, the BTK Killer; David Berkowitz, Son of Sam; and John Allen Muhammad and John Lee Malvo, the D.C. -

The Expressive/Transformative Process of Violence Lee Mellor A

I Kill, Therefore I Am: The Expressive/Transformative Process of Violence Lee Mellor A Thesis In the Individualized Program Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Individualized Program) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada July 2018 ©Lee Mellor, 2018 !"#!"$%&'()#&*+$,&-.( ,!/""0("1(2$'%)'-+(,-)%&+,! This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Lee Mellor Entitled: I Kill, Therefore I Am: The Expressive Transformative Theory of Violence and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Individualized program (INDI)) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: "#$%&! '&(!"#$&)*+!,*%++! !-./*&0$)!-.$1%0*&! '&(!2$&%0$!34&45#%0+6%! !-./*&0$)!/4! 7&48&$1! '&(!9&*8!:%*)+*0! !-.$1%0*&! '&(!-&%5!;%56*<! !-.$1%0*&! '&(!=1<!3>%??*0! -.$1%0*&! !'&(!@%A*6!@*06$/*+#! B#*+%+!3CD*&A%+4&! '&(!E*$0F,45#!G$C&*05*! =DD&4A*H!I<! '&(!,$5#*)!J*&8*&K(9&$HC$/*!7&48&$1!'%&*5/4&! !'*5*1I*&!LK!MNOP! '&(!7$C)$!Q44HF=H$1+K!'*$0! !35#44)!4?!9&$HC$/*!3/CH%*+ Abstract I Kill, Therefore I Am: The Expressive/Transformative Process of Violence Lee Mellor, Ph.D. Concordia University, 2018 Before the late-Industrial age, a minority of murderers posed their victims’ corpses to convey a message. With the rise of mass media, such offenders also began sending verbal communications to journalists and the authorities. Unsurprisingly, the 21st century has seen alienated killers promote their violent actions and homicidal identities through online communications: from VLOGs to manifestos, even videos depicting murder and corpse mutilation. -

Checkbook Journalism

Checkbook Journalism: It May Involve Free Speech Interests but It Is Not Free; Can Witnesses Be Prohibited from Selling Their Stories to the Media Under the First Amendment? CHRYSANTHE E. VASSILS* I. INTRODUCTION A woman witnesses a white Ford Bronco resembling the vehicle of a defendant in a high-profile double-murder case driving recklessly near the scene of the crime on the night of the murders. The woman is paid $5000 to tell her story on Hard Copy, a television tabloid show, and $2600 to recount her story for the Star, a supermarket tabloid newspaper. Afterwards, the prosecution declines to call the woman to testify at the grand jury proceeding because she now lacks credibility due to the profitable deal she made with the media.' In response to situations such as these, the California State Legislature enacted legislation that prohibits a witness to a criminal event or occurrence from accepting or receiving any compensation in exchange for providing information obtained as a result of witnessing that event or occurrence.2 * The author wishes to thank the members of her family and her close friends for their continued support and encouragement. I This incident occurred in the much publicized 0.1. Simpson double-murder case, People v. Simpson, No. BA097211 (Cal. Oct. 3, 1995). See Robin Clark, Tabloids Are Paying, but at a Cost: Journalism by Oeckbook Is a Big Problem in High-Profile Cases, PHRADELPHIA INQUIWR, July 3, 1994, at C1, C8; Henry Weinstein, Free-SpendingTabloid Media CauingJudidalConcemr, L.A. TIMEs, July 2,1994, at Al, A2. 2 CAL. -

The Writing of Criminal Minds Criminology and Handwriting Analysis

International Journal of Volume 1 Issue 4 Criminal Investigation 163-175 THE WRITING OF CRIMINAL MINDS CRIMINOLOGY AND HANDWRITING ANALYSIS Crineanu Iulia forensic expert, România Abstract Graphology is an experimental science which reveals, by studying the natural graphic movement of the subject, his personality, temper, intellectual behavior, professional and social capacities and his morbid inner predispositions. The product of such a niche analysis is a psycho- social- behavioral portrait, which resembles those of psychologists, focusing only on the interaction between the biological and psychic components reflected in people’s handwriting. It can be used, should the case allow it, as a very resourceful and coherent profiling instrument, meant to complete and enhance the information highlighted by forensic psychologists and psychiatrists, and it can also be of assistance to investigators in their interrogation activities, regardless it involves the suspect, victim or witnesses. Key words: graphology, psychology, forensic profiling, psychopathology, serial killers The entrapments of a criminal influencing the management of the investigation: investigation and it’s outcome. It is said that "nothing is easier than Even for the specialists, who are to denounce the evil doer and nothing more properly and rigorously trained, the difficult than understanding him". hardness of investigating such cases lays within the manner in which each of them While the investigators will, manages to accept their theories and somehow ironically, smile, analyzing the thoughts towards violence. first part of the statement above (in fact, the uncovering and proving of a criminal is According to Wertham’s theory1, a very complicated activity), we are more these difficulties – and the corresponding than certain that everyone agrees with the entrapments for the less experienced fact that understanding the psychological investigators – find their explanation in mechanisms, the determinations and the three different sources. -

The Death of Peter Intervallo Sr., MOURNING Retired Yonkers Police

Senate Resolution No. 975 BY: Senator HARCKHAM MOURNING the death of Peter Intervallo Sr., retired Yonkers Police Detective, family man and devoted member of his community WHEREAS, It is the sense of this Legislative Body to convey its grateful appreciation and heartfelt regret in recognition of the loss of a courageous and hardworking police officer who dedicated his purposeful life and career in faithful service to both his family and the residents of New York State; and WHEREAS, Peter Intervallo Sr. of Mahopac, New York, died on Saturday, May 8, 2021, at the age of 69; and WHEREAS, Peter Intervallo Sr. was a retired Yonkers police detective with 37 years on the job; as a young officer with just three years of service under his belt, he and his partner, Thomas Chamberlain, worked tirelessly as they linked together the final piece of evidence that would lead to the arrest and conviction of one of the nation's most notorious serial killers, David Berkowitz, commonly known as the Son of Sam; and WHEREAS, Peter Intervallo Sr. was 21 when he married his high school sweetheart, Joyce McEwan; they were the proud parents of three wonderful children; and WHEREAS, A great athlete, Peter Intervallo Sr.'s greatest aspiration after graduating high school was to become a professional basketball player but he ended up following his second-favorite career choice, law enforcement; in September of 1973, he was sworn into the Yonkers Police Department; and WHEREAS, In February 1977, Peter and Joyce Intervallo Sr. bought a home in Mahopac; it was just a few months later that the Son of Sam investigation really began to heat up and Peter Intervallo Sr. -

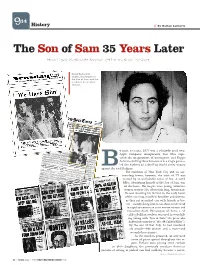

The Son of Sam 35 Years Later How David Berkowitz Forever Left His Mark on Yonkers

1 4 9 History // By Nathan Laliberte The Son of Sam 35 Years Later How David Berkowitz forever left his mark on Yonkers. David Berkowitz (right), also known as the Son of Sam, and the headlines he created (below). y most accounts, 1977 was a relatively good year. Apple Computer incorporated, Star Wars capti- vated the imaginations of moviegoers, and Reggie Jackson—hitting three home runs in a single game— led the Yankees to a thrilling World Series victory Bagainst the rival Dodgers. For residents of New York City and its sur- rounding towns, however, the start of ’77 was marred by an unshakable sense of fear. A serial killer, identifying himself as the Son of Sam, was on the loose. His targets were young, attractive women in their 20s, often with long, brown hair. He was shooting his victims in the early hours of the morning, mostly in Brooklyn and Queens, as they sat in parked cars with friends or lov- ers—usually firing four to six shots to the head in rapid succession so as to ensure certain and immediate death. His weapon of choice, a .44 caliber Bulldog revolver, was used in every kill- ing (along with “Son of Sam,” the press also dubbed the murderer “the .44 Caliber Killer”). By the end of that July, he had murdered six people—five women and a man—and wounded seven more. As the murders persisted, an increased sense of panic spread throughout the re- gion. Fathers were placing strict curfews on their daughters; the previously mundane American pastime of sitting in parked cars had suddenly become a poten- photo by michael polito 44 / APRIL 2012 / WWW.WESTCHESTERMAGAZINE.COM tially life-threatening activity (the police commissioner at the time, Michael Codd, even went so far as to issue a statement directing officers to insist that couples sitting in parked cars be ordered to move indoors); brunettes, scared to become a target of the killer, were donning blonde wigs in an attempt to avoid unwanted at- tention.