Carolina Planning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tale of Two Mayors

Race Relations in Boston: a Tale of Two Mayors, Raymond L. Flynn and Thomas M. Menino Ronda Jackson and Christopher Winship The Stuart Incident On October 23, 1989, Charles Stuart, a white, 30-year-old furrier, living in suburban Reading, Massachusetts, made a desperate 9-1-1 call to the Boston Police dispatcher. He reported that he had been shot. His wife, Carol Stuart, a lawyer, seven-months pregnant at the time, had also been shot, and was in the passenger’s seat next to him bleeding and unconscious. Though frightened and in shock, Stuart was able to provide some details of the crime. He told the dispatcher that he and his wife had just left a birthing class at a nearby hospital and gotten into their car parked near the Mission Hill housing project when a young black man in a hooded sweatshirt robbed and shot them both. The dispatcher stayed on the line with Stuart while police cruisers in the area found the Stuarts’ car and the two wounded victims.1 The Stuarts were rushed back to the same hospital where they had attended Lamaze class. Doctors performed an emergency c-section on Carol to remove the baby and, hopefully, save her life. Baby Christopher was put in the intensive care unit, but died 17 days later. Carol Stuart died six hours after the surgery. After giving police his account of the events, Charles Stuart was rushed into emergency surgery. He survived the surgery, but then went into a coma for several weeks after the shooting.2 Mayor Raymond Flynn and Police Commissioner Mickey Roache were immediately told of the shootings. -

Bands, Officials All Lined up for 'Bigger, Better' Parade

IN THIS ISSUE 48 PAGES I .....-.----,..---~ Day Tripping... Suggestions for a super autumn • • In New England! -This Week- Bands, officials all lined up for 'bigger, better' parade By Esther Shein "Allston-Brighton is going to sink into the ground this weekend under the wave of all the politicians and bands on Sunday," declares Parade Committee Chairman Joe Hogan. An estimated 25-30 bands are expected for this year's third annual parade. "We've got far more quality this year-it's going to be bigger and bet ter," he says proudly. The event-filled weekend kicks off Saturday with a cattle fair~ sponsored by the Brighton Congregational Church with assistance from the Brighton Board of Trade. In past years the BBOT hasheld fairs the day before the parade, but "some mer chants have felt the street fair was ~ounterproductive to business," ex plains president Frank Moy. "We wanted to do a family fair outside Brighton Center in [late] September, but the cost of liability insur ance .. ,made it not in our best in terest to do so." Instead, the BBOT has provided banners for the fair and will sell large, colorful posters of Allston-Brighton, with the proceeds going to benefit the Church's 160th anniversary next year. Dancers in elaborate costume delight youngsters along Washington Street during last year's Allston-Brighton Parade. This year's promises "We thought it would be good for ,,to be'the best one yet, according to Parade Chairman Joe Hogan. people to learn more about the church," says Reverend Paul Pitman. "We would like the church to once The Allston grand marshal is Stan memory of Jerome Brassil, Michael J. -

University Photographs (SUJ-004): a Finding Aid Moakley Archive and Institute [email protected]

University Photographs (SUJ-004): A Finding Aid Moakley Archive and Institute www.suffolk.edu/moakley [email protected] University Photographs (SUJ-004): A Finding Aid Descriptive Summary Repository: Moakley Archive and Institute at Suffolk University, Boston, MA Location: Moakley Law Library, 5th Floor Collection Title: SUJ-004: University Photographs, 1906-present, n.d. Dates: 1906-present, n.d. Volume: 28.9 cu.ft. 145 boxes Preferred Citation: University Photographs. John Joseph Moakley Archive and Institute. Suffolk University. Boston, MA. Administrative Information Restrictions: Copyright restrictions apply to certain photographs; researcher is responsible for clearing copyright, image usage and paying all use fees to copyright holder. Related Collections and Resources: Several other series in the University Archives complement and add value to the photographs: • SUA-007.005 Commencement Programs and Invitations • SUA-012 Office of Public Affairs: Press releases, News clippings, Scrapbooks • SUG-001 Alumni and Advancement Publications • SUG-002 Academic Publications: Course Catalogs, Handbooks and Guides • SUG-003: University Newsletters • SUG-004: Histories of the University • SUH-001: Student Newspapers: Suffolk Journal, Dicta, Suffolk Evening Voice • SUH-002: Student Journals • SUH-003: Student Newsletters • SUH-005: Yearbooks: The Beacon and Lex • SUH-006: Student Magazines Scope and Content The photographs of Suffolk University document several facets of University history and life including events, people and places, student life and organizations and athletic events. The identity of the photographers may be professionals contracted by the University, students or staff, or unknown; the following is a list of photographers that have been identified in the collection: Michael Carroll, Duette Photographers, John Gillooly, Henry Photo, Herwig, Sandra Johnson, John C. -

Good-Bye to All That: the Rise and Demise of Irish America Shaun O'connell University of Massachusetts Boston, [email protected]

New England Journal of Public Policy Volume 9 | Issue 1 Article 9 6-21-1993 Good-bye to All That: The Rise and Demise of Irish America Shaun O'Connell University of Massachusetts Boston, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp Part of the Nonfiction Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation O'Connell, Shaun (1993) "Good-bye to All That: The Rise and Demise of Irish America," New England Journal of Public Policy: Vol. 9: Iss. 1, Article 9. Available at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp/vol9/iss1/9 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in New England Journal of Public Policy by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Good-bye to The Rise and All That Demise of Irish America Shaun O'Connell The works discussed in this article include: The Rascal King: The Life and Times of James Michael Curley 1874-1958, by Jack Beatty. 571 pages. Addison -Wesley, 1992. $25.00. JFK: Reckless Youth, by Nigel Hamilton. 898 pages. Random House, 1992. $30.00. Textures of Irish America, by Lawrence J. McCaffrey. 236 pages. Syracuse University Press, 1992. $29.95. Militant and Triumphant: William Henry O'Connell and the Catholic Church in Boston, by James M. O'Toole. 324 pages. University of Notre Dame Press, 1992. $30.00. When I was growing up in a Boston suburb, three larger-than-life public figures defined what it meant to be an Irish-American. -

Baitett: 'I'm a Boston Fan' by John Becker Fore Running for the State Senate Last Year

BaITett: 'I'm a Boston fan' By John Becker fore running for the State Senate last year. His impossible dream came true when he was elected In August, 1983, the Boston Globe MagaziM ran a cover from a field of five candidates to the State Senate in a dis story in which the author accused Man.chusetts subur trict that includes Boston's Allston and Brighton neigh-· banites of taking from Boston its cultural, health and borhoods as well as Watertown, Belmont and parts of educational benefits and never giving anything in return. Cambridge. • . The author proposed a tax system whereby out-of-towners ''I want to represent working-class neighborhoods,'' says would contribute to the city whoee tax-exempt institutions the freshman senator, who has made headlines the past few · they utilize. The author, ironically, was Michael Barrett, weeks for leading the Senate floor fight to pass the nation's at that time a state representative from the suburban ~ first gay rights bill. "Representihg liberals is no fun;Jbey of Reading, Massachusetts. agree with me too much." Barrett, who c8ns himae1f a "Boston fan,'·' whose "im The gay rights bill is not a divisive issue in his district, possible dream" was to represent part of Massachusetts' greatest urban center, spent three terms in the House be- continued !>n page.11 Barrett: .__king olaM' hen? Published Weekly In Allston-Brighton Since 1884 Thursday, November 26, 1987 Vol. 102, No. 48 35 Cents By John Becker The euphoria that followed Mayor • Raymond Flynn's landslide re election vicM>ry a few weeke aao ap- ~;r:.:..::=a:: alter"'the shape of politics in Ward n:' When voters go to the poBs again in the March, 1988, Democratic presidential primary, they will have the opportunity to vote for a Ward 22 Democratic Committee lineup that is the result of a complicated behind-the scenes compromise that was worked out in the final hours before the N'ovember 6 deadline. -

Evolving Strategy of Policing: Case Studies of Strategic Change

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Evolving Strategy of Policing: Case Studies of Strategic Change Author(s): George L. Kelling ; Mary A. Wycoff Document No.: 198029 Date Received: December 2002 Award Number: 95-IJ-CX-0059 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Page 1 Prologue. Draft, not for circulation. 5/22/2001 e The Evolving Strategy of Policing: Case Studies of Strategic Change May 2001 George L. Kelling Mary Ann Wycoff Supported under Award # 95 zscy 0 5 9 fiom the National Institute of Justice, Ofice of Justice Programs, U. S. Department of Justice. Points ofview in this document are those ofthe authors and do not necessarily represent the official position ofthe U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Prologue. Draft, not for circulation. 5/22/2001 Page 2 PROLOGUE Orlando W. Wilson was the most important police leader of the 20thcentury. -

Key Issues Facing the Boston Public Schools Robert A

New England Journal of Public Policy Volume 10 | Issue 1 Article 24 6-21-1994 Key Issues Facing the Boston Public Schools Robert A. Dentler University of Massachusetts Boston Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp Part of the Education Policy Commons, Policy History, Theory, and Methods Commons, and the Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons Recommended Citation Dentler, Robert A. (1994) "Key Issues Facing the Boston Public Schools," New England Journal of Public Policy: Vol. 10: Iss. 1, Article 24. Available at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp/vol10/iss1/24 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in New England Journal of Public Policy by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Key Issues Facing the Boston Public Schools Robert A. Dentler This article is the third examination of the six issues the author identified in "Some Key Issues Facing Boston's Public Schools in 1984, "following the November 1983 election of the first thirteen-member Boston School Committee. He revisited these is- sues in a 1988 report and now assesses how the policy leadership of the system fared in dealing with these challenges during the past decade. He discusses other issues at the close of this article. Writing from a sociological point of view, Dentler is primar- ily concerned with the question of how well the public school districts and their school staff are able to provide optimal learning opportunities to all students. -

1966-06-05 University of Notre Dame Commencement Program

One Hundred and Twenty-first Commencement Exercises OFFICIAL JUNE ExERCISES THE UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE DAME NoTRE DAME, INDIANA THE GRADUATE ScHooL THE LAw ScHooL THE CoLLEGE oF ARTs AND LETTERS THE CoLLEGE OF SciENCE THE CoLLEGE OF ENGINEERING THE CoLLEGE oF BusiNEss ADMINISTRATION On the University Mall At 2:00 p.m. (Eastern Standard Time) Sunday, June' 5, 1966 1 ! i PROGRAM PROCESSIONAL CITATIONS FOR HoNORARY DEGREES by the Reverend John E. Walsh, C.S.C. Vice-President for Academic Affairs THE CoNFERRING OF HoNORARY DEGREEs by the Reverend Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C. President of' the University PRESENTATION OF CANDIDATES FOR DEGREES by the Reverend Paul E. Beichner, C.S.C. Dean of the Graduate School by Joseph O'Meara Dean of the Law School by the Reverend Charles E. Sheedy, C.S.C. Dean of the Coiiege of Arts and Letters by Frederick D. Rossini Dean of the Coiiege of Science by Norman R. Gay Dean of the Coiiege of Engineering by Thomas T. Murphy Dean of the Coiiege of Business Administration THE CoNFERRING oF DEGREES by the Reverend Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C. ·· President of the University PREsENTATION oF THE LAY FACULTY AwARD PREsENTATION oF THE PRoFEssoR THoMAs MADDEN . FAcULTY AwARD CoMMENCEMENT AnDREss by Lady Jackson London, England THE BLESSING . by His Eminence Juan Cardinal Landazuri Ricketts Archbishop of Lima, Peru 3 Degre~s Conferred The University of Notre Dame announces the conferring of: The Degree of Doctor of Laws, honoris causa, on: Honorable David E. Bell, Washington, D. C. Reverend Joseph M. Bochenski, O.P., Fribourg, Switzerland Mr. -

Governance and Urban School Improvement: Lessons for New

Governance and Urban School Improvement: Lessons for New Jersey From Nine Cities THE INSTITUTE ON EDUCATION LAW AND POLICY RUTGERS - NEWARK Ruth Moscovitch Alan R. Sadovnik Jason M. Barr Tara Davidson Teresa L. Moore Roslyn Powell Paul L.Tractenberg Eric Wagman Peijia Zha i TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES .............................................................................................................. v LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................... vi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................ vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 1 I. BACKGROUND: SCHOOL GOVERNANCE SYSTEMS IN THE UNITED STATES ............................................................................................................................................. 3 FORMS OF GOVERNACE OF SCHOOL DISTRICTS ............................................... 3 BRIEF HISTORY OF MAYORAL INVOLVEMENT IN PUBLIC EDUCATION ..... 4 CONTEMPORARY FORMS OF MAYORAL INVOLVEMENT IN SCHOOL GOVERNANCE AND “CONTROL” ............................................................................ 5 ARGUMENTS IN SUPPORT OF AND AGAINST STRONG MAYORAL INVOLVEMENT ........................................................................................................... 6 Arguments in Support of Strong Mayoral Involvement ............................................ -

For Dorchester and I’M Happy to Have Been Able to Work Closely with Guard at Mat- Our Many Neighbors Who Make It Such a Great Place

Dorchester Reporter “The News and Values Around the Neighborhood” Volume 31 Issue 1 Thursday, January 2, 2014 50¢ Farewell, Dorchester ‘Service’ events to mark big Walsh weekend By Gintautas Dumcius been nice,” Walsh said. news eDitor “It’s fine, I don’t have Marty Walsh of Savin a problem with it,” he Hill will be sworn in as added. the next mayor of Boston Walsh said he and his on Jan. 6 on the campus girlfriend Lorrie Higgins of his alma mater, Boston had dinner with Menino College. The ceremony and his wife Angela last starts at 10 a.m. at the week. Conte Forum. Walsh’s inaugural Walsh will resign his festivities, which will 13th Suffolk House seat start on Friday Jan. 3 on Jan. 3, days before and stretch through the he takes the oath of weekend and culminate office, which will be ad- with a party at the Hynes ministered by Roderick Convention Center on Ireland, the chief justice Monday night, will have of the state Supreme a public service compo- Judicial Court. nent. Walsh said this O u t g o i n g M a y o r week he is seeking to Thomas Menino won’t keep civic engagement be attending. Walsh told alive after the first open reporters this week that race for mayor in 30 he did not feel “slighted years. at all” by Menino declin- Volunteer events in ing to appear at the Dorchester and Mat- swearing-in. “It would’ve (Continued on page 17) Work to begin on St. Kevin’s project By Gintautas Dumcius of community space, news eDitor instead of a replacement Mayor Thomas Me- for the Uphams Corner nino and officials from Branch Library, which the Boston Archdiocese city and project officials on Monday dug into the had initially considered. -

©2011 Samonne M. Montgomery ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

©2011 Samonne M. Montgomery ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ORGANIZING FOR REGIME CHANGE: AN ANALYSIS OF COMMUNITY UNIONISM IN LOS ANGELES, 2000 - 2010 By SAMONNE MONIQUE MONTGOMERY A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Planning and Public Policy written under the direction of James DeFilippis and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2011 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Organizing For Regime Change: An Analysis of Community Unionism in Los Angeles, 2000 - 2010 by SAMONNE MONIQUE MONTGOMERY Dissertation Director: James DeFilippis Since the 1990s in Los Angeles, working class residents have crossed ethnic, religious, and spatial divides to form working class coalitions aimed at enacting social, economic, and environmental justice. This trend, referred to as community unionism, challenges elites‘ narrow distribution of scarce public resources by fighting for community-driven reforms that advance the interests of broadly-shared prosperity (Tattersall, 2010; Reynolds, 1999). Using document analysis and semi-structured interviews, I analyze three broad- based community-labor coalitions that emerged in Los Angeles between 2000 and 2010 to understand how urban governance has changed – both as a result of the progressive community‘s recent coalition building efforts and as a result of the -

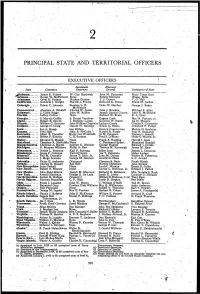

State and Territorial Officers

r Mf-.. 2 PRINCIPAL STATE AND TERRITORIAL OFFICERS EXECUTIVE- OFFICERS • . \. Lieutenant Attorneys - Siaie Governors Governors General Secretaries of State ^labama James E. Folsom W. Guy Hardwick John M. Patterson Mary Texas Hurt /Tu-izona. •. Ernest W. McFarland None Robert Morrison Wesley Bolin Arkansas •. Orval E. Faubus Nathan Gordon T.J.Gentry C.G.Hall .California Goodwin J. Knight Harold J. Powers Edmund G. Brown Frank M. Jordan Colorajlo Edwin C. Johnson Stephen L. R. Duke W. Dunbar George J. Baker * McNichols Connecticut... Abraham A. Ribidoff Charles W. Jewett John J. Bracken Mildred P. Allen Delaware J. Caleb Boggs John W. Rollins Joseph Donald Craven John N. McDowell Florida LeRoy Collins <'• - None Richaid W. Ervin R.A.Gray Georgia S, Marvin Griffin S. Ernest Vandiver Eugene Cook Ben W. Fortson, Jr. Idaho Robert E. Smylie J. Berkeley Larseri • Graydon W. Smith Ira H. Masters Illlnoia ). William G. Stratton John William Chapman Latham Castle Charles F. Carpentier Indiana George N. Craig Harold W. Handlpy Edwin K. Steers Crawford F.Parker Iowa Leo A. Hoegh Leo Elthon i, . Dayton Countryman Melvin D. Synhorst Kansas. Fred Hall • John B. McCuish ^\ Harold R. Fatzer Paul R. Shanahan Kentucky Albert B. Chandler Harry Lee Waterfield Jo M. Ferguson Thelma L. Stovall Louisiana., i... Robert F. Kennon C. E. Barham FredS. LeBlanc Wade 0. Martin, Jr. Maine.. Edmund S. Muskie None Frank Fi Harding Harold I. Goss Maryland...;.. Theodore R. McKeldinNone C. Ferdinand Siybert Blanchard Randall Massachusetts. Christian A. Herter Sumner G. Whittier George Fingold Edward J. Cronin'/ JVflchiitan G. Mennen Williams Pliilip A. Hart Thomas M.