University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan the UNIVERSITY of OKLAHOMA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ghost Stories Event at Murrell Home Doaksville Candlelight Tours Upcoming Events at Pawnee Bill Ranch

Vol. 46, No. 10 Published monthly by the Oklahoma Historical Society, serving since 1893 October 2015 Ghost Stories event at Murrell Home Doaksville Candlelight Tours For the twenty-third consecutive year, the George M. Murrell On Friday, October 16, and Saturday, October 17, Fort Tow- Home in Park Hill will be the backdrop for storytellers spinning son will host its annual Doaksville Candlelight Tours. During yarns about the “Hunter’s Ghost” and other chilling accounts. this event, attendees will learn about life in the Choctaw Nation The event will be held on Friday, October 23, and Saturday, during the Civil War (1861–65). October 24. Tours leave from the gate leading to Doaksville at the north “This family-oriented program will feature various storytellers end of the Fort Towson Cemetery. The candlelight tours begin in a number of rooms telling tales about the Murrell Home, the at 6:30 p.m., with the last tour starting at 9:30 p.m. Admission Cherokee Nation, and other local ghost stories,” said Amanda for the tour is $6 per person, Pritchett, a historical interpreter for the OHS. “The Ghost Sto- and children six and under ries are one of our most popular events of the year. Many peo- are free. The event is spon- ple return every year,” said Pritchett. sored by the OHS, Friends Ghost stories related to the 1845 plantation mansion are of Fort Towson, and the Fort documented as early as the 1930s. One story, the “Hunter’s Towson Volunteer Fire De- Ghost,” is the legend that grew out of the years George Murrell partment. -

Seven Female Photographers of the Oklahoma and Indian Territories, 1889 to 1907

SEVEN FEMALE PHOTOGRAPHERS OF THE OKLAHOMA AND ~NDIAN TERRITORIES, 1889 TO 1907 By JENNIFER E. TILL Bachelor of Arts University of Maryland College Park, Maryland 1994 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS July, 1997 SEVEN FEMALE PHOTOGRAPHERS OF THE OKLAHOMA AND INDIAN TERRITORIES, 1889 TO 1907 Thesis Approved: ':;t' Ji. ~ Thesis Adviser __GiCnU>L& k ~ t!t .c:f--lf.r{ /) .• :!...J-. i ti~~- t//d----{l ;JI,~ (!__ {!~ Dean of the Graduate College ii PREFACE This study was conducted to examine female photographers - four professionals and three amateurs - active in the Oklahoma and Indian Territories from approximately 1889 until about 1907. These women offer valuable insights into the history of photography and women's involvement in that history. They appear in this study because examples of their photography exist at the Oklahoma Historical Society and the University of Oklahoma. They were researched further through the United States Census Records and city directories. The results of these record searches are discussed in Chapters One and Two in conjunction with a discussion of the individual women. This study is organized to place the seven women from the Oklahoma and Indian Territories into the wider history of photography and women's involvement in that history. Chapter One contains information about the trends in professional photography from approximately 1889 until 1907. Incorporated into this general history are four specific women from the Territories: Emma Coleman, Georgia Isbell 111 Rollins, Persis Gibbs, and Alice Mary Robertson. -

2003 Trail News

PRSRT STD U.S. POSTAGE Trail of Tears National Historic Trail Trail PAID of LITTLE ROCK, AR Tears PERMIT 196 Association Trail of Trail News 1100 N.University, Suite 143 Tears Little Rock, AR 72207-6344 Association Partners Produce Draft Interpretive Plan One of the several action items identified ing on a long-range vision for trail-wide during the strategic plan for the Trail of interpretive programming that will take us Tears National Historic Trail (TRTE) in into the next five to ten years. The final Memphis last summer was the develop- CIP document is intended to define and ment of a Comprehensive Interpretive Plan guide the trail-wide interpretive program (CIP) for the Trail. The first step in devel- consistent with achieving the Trail’s goals oping that plan was taken this April when for interpretation—increasing people’s a group of partners gathered again in Memphis. Representatives from the tribes, “The comment period for the national office and state chapters of the CIP is June and July. Trail of Tears Association, researchers, the Don’t miss this opportunity National Trails System Office – Santa Fe, to provide your input!” Sharon Brown (left) and Kim Sikoryak (right) facili- the US Army Corps of Engineers, and the tate the CIP meeting in early April. USDA Forest Service spent two days work- understanding and appreciation of the sig- Completion of the draft CIP is scheduled nificance of the TRTE. EXPERIENCE YOUR AMERICA for early June. The draft will then be cir- INSIDE THIS ISSUE culated to a wide scope of Trail partners Interpretive Planners/Specialists, Kim for review. -

Trail of Tears Curriculum Project Under Construction

Newsletter of the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail Partnership • Spring 2019 – Number 31 TRAIL OF TEARS CURRICULUM PROJECT UNDER CONSTRUCTION University of North Alabama PICTURED: At the spring 2018 TOTA national LEFT TO RIGHT: BRIAN board meeting, a vote to partner with CORRIGAN, PUBLIC HISTORIAN/ MSNHA, DR. JEFFREY BIBBEE, the University of North Alabama to PROFESSOR FROM UNA/ALTOTA create a national curriculum for k-12 MEMBER , JUDY SIZEMORE, students on the Trail of Tears cleared MUSCLE SHOALS NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA/ALTOTA the board and gave partners a green MEMBER, ANNA MULLICAN light to begin laying the framework for ARCHAEOLOGIST/EDUCATOR- TOTA’s first ever large-scale curriculum OAKVILLE INDIAN MOUNDS, ANITA FLANAGAN, EASTERN project. BAND OF CHEROKEE INDIANS CITIZEN/ALTOTA BOARD Since then, there has been much MEMBER, DR. CARRIE BARSKE- CRAWFORD, DIRECTOR/MUSCLE ground covered to begin building SHOALS NATIONAL HERITAGE partners for the curriculum with not AREA, SETH ARMSTRONG PUBLIC only TOTA and UNA but also with HISTORIAN/PROFESSOR/ALTOTA MEMBER, SHANNON KEITH, the Muscle Shoals National Heritage ALTOTA CHAPTER PRESIDENT. Area. Just under one year out, our UNA and TOTA are committed to creating Educating students about the trail, who was Alabama planning group has secured something truly transformational for impacted, and the consequences for everyone $20,000.00 from the Muscle Shoals teachers around the country.” involved is essential. This cross-curriculum National Heritage Area, $25,000.00 project will allow teachers to introduce the from the University of North Alabama Dr. Carrie Barske-Crawford, Director of subject into their classes in multiple ways, and another $100,000.00 in in-kind the Muscle Shoals National Heritage hopefully enforcing just how important this contributions from UNA. -

Philanthropy

2016 Annual Report GROWINGPhilanthropy | occf.org “A society grows great when men plant trees whose shade they know they shall never sit in.” Greek Proverb Dear Donors and Friends, Forty-seven years ago, John E. Kirkpatrick and a group of forward-thinking community leaders took a bold and pioneering step. Embracing an innovative idea of securing lasting charitable support through endowment, they created a foundation for the community. They planted the seeds of support that grew into an enduring community resource, enabling caring individuals to make a charitable impact for years to come. Our 2016 Annual Report recognizes our community’s generous donors and highlights the collective impact we’ve made during the fiscal year that ended June 30, 2016. But it also shares the stories of donors who believe that together we have the power to make a real difference. In Fiscal Year 2016, $34 million in grants benefited 1,800 charitable organizations and the thousands of individuals they serve. In addition, $1.5 million in scholarships helped 600 students further their education. This impact in the community was made possible through $44 million in gifts received from 1,700 donors. However, we strive to do much more than distribute grant dollars. By bringing together partner organizations and donor resources, we are creating effective solutions that benefit the whole community. During the last fiscal year: - We helped make major improvements to 14 public parks and school playgrounds in central Oklahoma, creating more usable public spaces for the community. - Through our Wellness Initiative, we are taking action to create a healthier community and supported nine projects to encourage healthy lifestyles among central Oklahoma residents. -

Cherokee County Community Health Coalition Cherokee County 2011 About Us

Cherokee County Community Health Coalition Cherokee County 2011 About Us... Cherokee County Health Services County Health Services Council and Council The founding of Cherokee County the Cherokee County Community Community Health Coalition Northeastern State University Health Coalition. Over one hundred (CCCHC) was 17 years ago in 1994, Cookson Hills Community Action local and national experts have de- as a small informal group of area Communities of Excellence Tobacco veloped SMRTNET over four years Control Program health care providers gathered to be- at a cost of over $4 million based on gin a dialogue to address the health NEO Health an AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare needs of the area. Through their vi- Tahlequah Daily Press Research and Quality) grant and sion, and with grant funding from the Health Services Council Oklahoma sources in the Cherokee Robert Wood Johnson and Kellogg Boys & Girls Club of Tahlequah County area. The Agency for Foundations in 1998, this coalition Go Ye Village Healthcare Research and Quality became one of three pilot programs Tahlequah City Hospital featured SMRTNET in a report for Oklahoma Turning Point. The pur- Chamber of Commerce published in September 2010 high- pose of the CCCHC is to provide a The Current Alternative News lighting eight quality improvement forum whereby its independent mem- stories and their application of Help In Crisis bers may join together to plan, share health IT across the country. The Secure Medical Records Transfer resources, and develop strategies to Cherokee County lies in the heart of the Illinois assist in the implementation of pro- Network (SMRTNET) is a publicly River Valley, with miles of shoreline on Lake grams addressing the health status and managed HIE (Health Information Tenkiller and access to Fort Gibson Lake. -

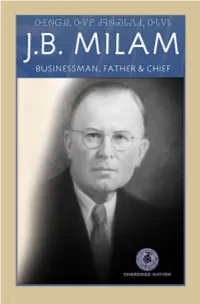

JB Milam Is on the Top Row, Seventh from the Left

Copyright © 2013 Cherokee National Historical Society, Inc. Cherokee National Historical Society, Inc, PO Box 515, Tahlequah, OK 74465 Design and layout by I. Mickel Yantz All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronically or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage system or retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Businessman,J.B. Father,Milam Chief A YOUNG J. B. MILAM Photo courtesy of Philip Viles Published by Cherokee Heritage Press, 2013 3 J.B. Milam Timeline March 10, 1884 Born in Ellis County, Texas to William Guinn Milam & Sarah Ellen Couch Milam 1887, The Milam family moved to Chelsea, Indian Territory 1898, He started working in Strange’s Grocery Store and Bank of Chelsea 1899, Attended Cherokee Male Seminary May 24, 1902 Graduated from Metropolitan Business College in Dallas, TX 1903, J.B. was enrolled 1/32 degree Cherokee, Cherokee Roll #24953 1904, Drilled his first oil well with Woodley G. Phillips near Alluwe and Chelsea 1904, Married Elizabeth P. McSpadden 1905, Bartley and Elizabeth moved to Nowata, he was a bookkeeper for Barnsdall and Braden April 16, 1907 Son Hinman Stuart Milam born May 10, 1910 Daughter Mildred Elizabeth Milam born 1915 Became president of Bank of Chelsea May 16, 1916 Daughter Mary Ellen Milam born 1933 Governor Ernest W. Marland appointed Milam to the Oklahoma State Banking Board 1936 President of Rogers County Bank at Claremore 1936 Elected President of the Cherokee Seminary Students Association 1937 Elected to the Board of Directors of the Oklahoma Historical Society 1938 Elected permanent chairman for the Cherokees at the Fairfield Convention April 16, 1941 F.D.R. -

Download the Guide (PDF)

For teachers and youth group leaders Designed to accompany the Hunter's Home Living History Program Compiled and designed by Amanda Burnett Published by the Oklahoma Historical Society Dear Educators: This teacher’s curriculum guide was devised to help teachers, youth group leaders, and other educators make a connection with Hunter's Home before coming to visit. Inside, you will find history on the house and occupants and general information on life in the mid-1800s. The guide is meant to complement a visit to the Hunter's Home, Daniel Cabin, and the grounds. The target age group is fourth and fifth grade, but many of the activities can be suitable for any age. The guide covers topics in the 1840–1865 time period. The Daniel Cabin living history program is set in 1850. The year 1850 was significant to the Cherokee Nation and the United States for several reasons. First, the gold rush was in full swing in California, and many Cherokees traveled there to seek fortunes for their families. The other reason why 1850 is ripe for interpretation is that a diary exists from Murrell’s niece, Emily, who came to visit the house that year. As a young woman, Emily recorded many of the activities at Park Hill and gave us insight into the daily lives of the people who lived in the home. With such personal accounts, the staff can better interpret the site in a particular time period. If you have any questions about the Hunter's Home education program or would like to schedule a tour for your class or group, please contact the site at 918-456-2751 or email us at [email protected]. -

2020 Real Property Asset Report 2 Introduction

2020 OKLAHOMA REAL PROPERTY ASSET REPORT Contents Oklahoma State Capitol in the winter INTRODUCTION . 3 METHOD OF COLLECTING AND COMPILING DATA . 4 NUMBERS AT-A-GLANCE . 5 HIGHLIGHTED PROPERTIES . .11 . AGENCY PROFILES . 17 COUNTY PROFILES . 31 REPORT OF UNDERUTILIZED PROPERTIES . 34 REPORT OF 5% MOST UNDERUTILIZED PROPERTIES . 35 INVENTORY LISTS . 36 APPENDIX A . 38 APPENDIX B . 42 This publication is issued by the Office of Management and Enterprise Services as authorized by Title 62, Section 34. Copies have not been printed but are available through the agency website. This work is licensed under a creative Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. 2020 REAL PROPERTY ASSET REPORT 2 INTRODUCTION Since the enactment of the Oklahoma State Government Asset Reduction and Cost Savings Program in 2011, the Office of Management and Enterprise Services has published an annual report of all property owned or leased by the State of Oklahoma. The 2020 Oklahoma Real Property Asset Report is the ninth publication of this statutorily required report. All agencies, boards, commissions, and public trusts with the state as a beneficiary (ABCs) are surveyed annually to capture changes, corrections and additional data on all property owned or leased by the State of Oklahoma. The information from the surveys is compiled and published online in an interactive format, and links to the data are found in this report. Additionally, OMES analyzes the data to provide an informative, at-a- glance summary of the data submitted by the agencies. Real property is divided into the categories of owned and leased and then further subdivided by agency and location to calculate the sum of the square footages and acreages of the properties. -

OHS Assists Film Makers in Cherokee Trail of Tears Documentary

Vol. 37, No. 4 Published monthly by the Oklahoma Historical Society, serving since 1893 April 2006 OHS assists film makers in Cherokee Trail of Tears documentary From February 17 through February 19 at Fort Gibson and the Murrell Home, in the midst of a winter ice and snow storm, American Revolutionary Productions filmed The Cherokees: Road to Removal. The documentary is a re-creation of the Cherokees’ Trail of Tears experience. The film company, headed by Richard Wormser, David Smith, and Gilles Carter, has released many award-winning documentaries and has taken on the task of showing the plight of Cherokee removal from the American South to new homes in present eastern (Karen Wenk photo) Oklahoma. Through the Outreach Division and its Special Projects Director Whit Edwards, the Oklahoma Historical Society supplied site locations, the wardrobe, and in some instances, the actors and staff for the project. Casting was done through the Cherokee Heritage Center and included many of the reenactors among the Oklahoma Historical Society volunteers. Snow and ice reduced the numbers of reenactors who could help with the project, but the severe weather proved to be a perfect backdrop. The documentary will be distributed in October. The beneficiaries will be the Arkansas public schools and the Oklahoma public libraries, which will receive copies free of charge. The film will be broadcast on the History Channel in the fall of 2006. Photographer Karen Wenk produced still shots to document the filming. According to director David Smith, “Without Whit Edwards, the shoot simply would not have happened, and we owe him and the Society a great deal. -

Trail of Tears

44 M Louisville is INDIANA si ss ip R p iver i ILLINOIS 65 io Rolla Snelson-Brinker Cabin Oh MISSOURI Massey Ri ve 57 Iron 55 r Works Laughlin Elizabethtown KANSAS Park Camp Trail of Tears Ground McGinnis Cemetery ver State Park Cemetery Ri KENTUCKY Trail Segment Northern Hildebrand REMOVAL CAMPS Anna Berry's Ferry Route Bollinger Mill Jackson After being forcibly removed from Route Crabb-Abbott Farm Northern their homes in Georgia, Alabama, Mantle Rock Route Tennessee, and North Carolina, most Cape Girardeau Ohi o 24 Cherokee are moved into 11 removal Springfield camps—10 in Tennessee and one in Wilson's Creek Big Spring Alabama. There they await the start TRAIL’S END National Battlefield of an 800-mile journey. Bowling Green Cu m The last detachment arrives in ROSS’S LANDING ber land Indian Territory on March 24, Location: Present-day Chattanooga, T e 1839. The Cherokee are promised n Tennessee. From June 6 to June 17, 1838, subsistence rations through March BENGE ROUTE 57 n Hopkinsville Trail of Tears Commemorative Park three detachments are forced to leave e Riv Columbus-Belmont s er 1, 1840, in compliance with the Starting from Fort Payne, on September s their homeland for Indian Territory. State Park e Treaty of New Echota. 28, 1838, Cherokee leader John Benge e Gray's Inn Pea Ridge escorts 1,079 Cherokee toward present- FORT CASS National day Stilwell, Oklahoma. VANN’S PLANTATION Location: Present-day Charleston, Polson Cemetery Military Port Royal State Park Location: Present-day Wolftever Creek, Tennessee. From August 23 to Park Benge Tennessee. -

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Anne Ross Piburn Collection Piburn, Anne Ross. Papers, 1883–1958

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Anne Ross Piburn Collection Piburn, Anne Ross. Papers, 1883–1958. .25 foot. Collector. Programs (1937–1958) of the yearly reunions of Cherokee Seminary graduates; a report (1955) regarding the old Murrell home in Tahlequah, Indian Territory; a report (1953) regarding New Echota, Cherokee Nation; a publication (1954) of the Cherokee Foundation, Inc., entitled Tsa La Gi’ Ga Nah Se Da’; an undated list of freedmen granted Cherokee citizenship; and memorials (1883–1899) of the Cherokee Nation and its delegation to the U.S. Congress. _____________ Box P-19 Folder: 1 Homecoming Programs of Cherokee Seminaries Students Association, 1937, 1938, 1947, 1953, 1954, 1955, 1958. Brochure of Northeastern Teachers College. 2 Genealogical notes on the Ross family. 3 Miscellaneous newspaper clippings regarding World War I, U.S. veteran and military history, Abraham Lincoln, and current events, circa 1917-1920. 4 Newspaper and manuscripts on the Murrell home. 5 Negative copy of the Civil War discharge papers for Jacob A. Pyburn, 1865; and a negative copy of a blank oath of identity form, with the name of Robert Ross written on it. 6 a) "New Echota, Capital of the Cherokee Nation, 1825-1830, "A Report to the Georgia Historical Commission, October 18, 1953, by Henry T. Malone. b) Letter from Henry T. Malone regarding the New Echota Restoration Project. 7 a) Typed one-page report, “Park Hill Centennial.” b) Green and white printed map showing historic sites in Tahlequah, with handwritten corrections, undated. 8 TSA-LA-GI' GA-NAH-SE-DA' (The Cherokee Ambassador), Volume 1, No.