archived as http://www.stealthskater.com/Documents/Endurance_01.doc read more great discoveries at http://www.stealthskater.com/Science.htm#NOVA note: because important web-sites are frequently "here today but gone tomorrow", the following was archived from http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/transcripts/2906_shacklet.html on February 4, 2004 . This is NOT an attempt to divert readers from the aforementioned web-site. Indeed, the reader should only read this back-up copy if it cannot be found at the original author's site. Shackleton's Voyage of Endurance

Narrator: They were alone, trapped in the ice-covered waters of Antarctica's treacherous seas. "Frozen," as one man put it, "like an almond in the middle of a chocolate bar."

The year was 1915, and the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition had ground to a halt. 28 men fought unceasingly to save their ship from the onslaught of the ice. The outside world had no idea of their predicament as they drifted helplessly towards uncharted waters. With civilization over 1000 miles away, only static crackling could be heard through their radio headset. Confronted with the approach of the Antarctic winter and the coldest climate on Earth, they were about to be pushed to the limits of human endurance.

Peter Wordie (son of James Wordie): My father never -- to any of us, his children-- ever discussed the Endurance expedition. Occasionally an odd statement came out. But he was extraordinarily reticent. He never let us read his diaries when he was alive. They were locked up.

Alexander Macklin (son of Endurance doctor Alexander Macklin): In some ways, it was almost as if the situation never happened. And that's probably because my father always felt that without having been there, without having experienced, without having suffered and endured, that it would be very difficult for anybody outside that to understand.

Mary Crean OBrien (daughter of Endurance seaman Tom Crean): My father didn't speak too much about the Antarctic. I often wondered was it too hard? Did he want to forget it? But he did say they had a tough time. And the one thing he did show us now was his ears. They had suffered frostbite. They were like boards!

Narrator: One man above all bore responsibility for their survival: Sir Ernest Shackleton. A veteran of Polar exploration, he knew that anyone trapped in this hostile region would be stalked by starvation, insanity and death. For Shackleton, the stark reality of their plight was terrifyingly clear. With no chance of rescue, it was up to him to get his men out alive.

Their struggle would become legend, a testament to the human spirit, and an epic adventure of a heroic age.

1 Narrator: In 1913, an Anglo-Irish explorer named Sir Ernest Shackleton set an ambitious goal:

Ernest Shackleton {voiceover]: After the conquest of the South Pole, there remained but one great object -- the first crossing of the Antarctic continent from sea-to-sea. The distance will be roughly 1800 miles. Half will be over unknown ground. Every step will advance geographic science. It will be the greatest Polar journey ever attempted.

Roland Huntford (historian and author): Shackleton was an inordinately ambitious man. He was searching for greatness, for reputation. And it just so happened that Polar exploration offered him the opportunity.

Jonathan Shackleton (Ernest Shackleton's cousin): He had a huge amount of energy. He was full of enterprise. He was very good-natured. And anybody who ever met him saw that this was someone who was going to get on with people, and he was going to get on with what he wanted to do in life.

Narrator: Shackleton left boarding school at age 16 and joined the navy to sail around the World. But he was soon drawn to the glory of exploration as he accompanied Robert Scott on his attempt to reach the South Pole in 1902. Like beasts of burden, they man-hauled supplies but failed to bring enough to ward off cold, starvation, and scurvy. Over 400 miles from the Pole, they were forced to give up.

At 28, Shackleton's ravaged face betrayed the suffering he had endured. Scott dismissed him as "our invalid" and sent him home to England. It was a devastating indictment, but not one shared by the public which idolized these men as heroes.

6 years later, Shackleton launched his own assault on the Pole with Siberian ponies. Only 97 miles from the prize, he made the agonizing decision to turn back rather than risk the lives of his men.

While praising Shackleton for lifting the veil from Antarctica, Norwegian explorer Roald Amundson noted,

Roald Amundson {voiceover}: If Shackleton had been equipped in dogs and -- above all -- skis, and understood their use, well then the South Pole would have been a closed chapter.

Narrator: 2 years later, Amundson claimed the Pole for Norway. Undaunted, Shackleton applied his ambition to the crossing of the continent.

Jonathan Shackleton: Shackleton was the most charming, persistent beggar you have ever met. And he had a wonderful way of being able to get money for his expeditions. His outgoing, open approach to things disarmed people. I'm not saying disarmed them of their money. But people took an instant liking to him.

Narrator: Born into the middle-class, Shackleton's marriage to the affluent Emily Dorman helped him court patrons. With gifts and loans, he purchased a ship and christened her the Endurance after his family motto, "By Endurance we conquer."

As war threatened Europe, Shackleton offered his ship and service to the British Navy which declined, convinced the fighting would be over in months. 2 Left alone to raise their 3 children, Emily wrote,

Emily Shackleton {voiceover}: I think fairy tales are to be blamed for half the misery in the World. I never let my children read "and they were married and lived happily ever after."

Narrator: On the eve of World War I, the Endurance departed for Antarctica. On board were 69 excited sled dogs and a 28-man crew of seamen, scientists, adventurers, and escapists. For Shackleton, personality mattered more than a man's experience with ice and snow.

Julian Ayer (grandson of Colonel Thomas Orde-Lees): My grandfather met Ernest Shackleton by replying to an advertisement that was in the personal columns of The Times that read, "Men wanted for hazardous journey. Small wages. Bitter cold. Long months of complete darkness. Constant danger. Safe return doubtful. Honor and recognition in case of success. Ernest Shackleton." And such an advertisement would be absolute catnip to my grandfather Colonel Orde-Lees. He couldn't resist it!

Tom McNeish (grandson of Endurance carpenter Chippy McNeish): My grandfather Chippy McNeish saw an advertisement in the paper and it said you might not return. So he went and seen about it and got it.

Narrator: Around 5,000 men applied. Shackleton's sheer willpower and personal magnetism made him an irresistible leader.

Roland Huntford: This has got to do with some force of character -- some flame that burns within a man. You can't learn it. You can't develop it. It's something you radiate. He had this.

3 "MEN WANTED: FOR HAZARDOUS JOURNEY. SMALL WAGES, BITTER COLD, LONG MONTHS OF COMPLETE DARKNESS, CONSTANT DANGER, SAFE RETURN DOUBTFUL. HONOUR AND RECOGNITION IN CASE OF SUCCESS. SIR ERNEST SHACKLETON"

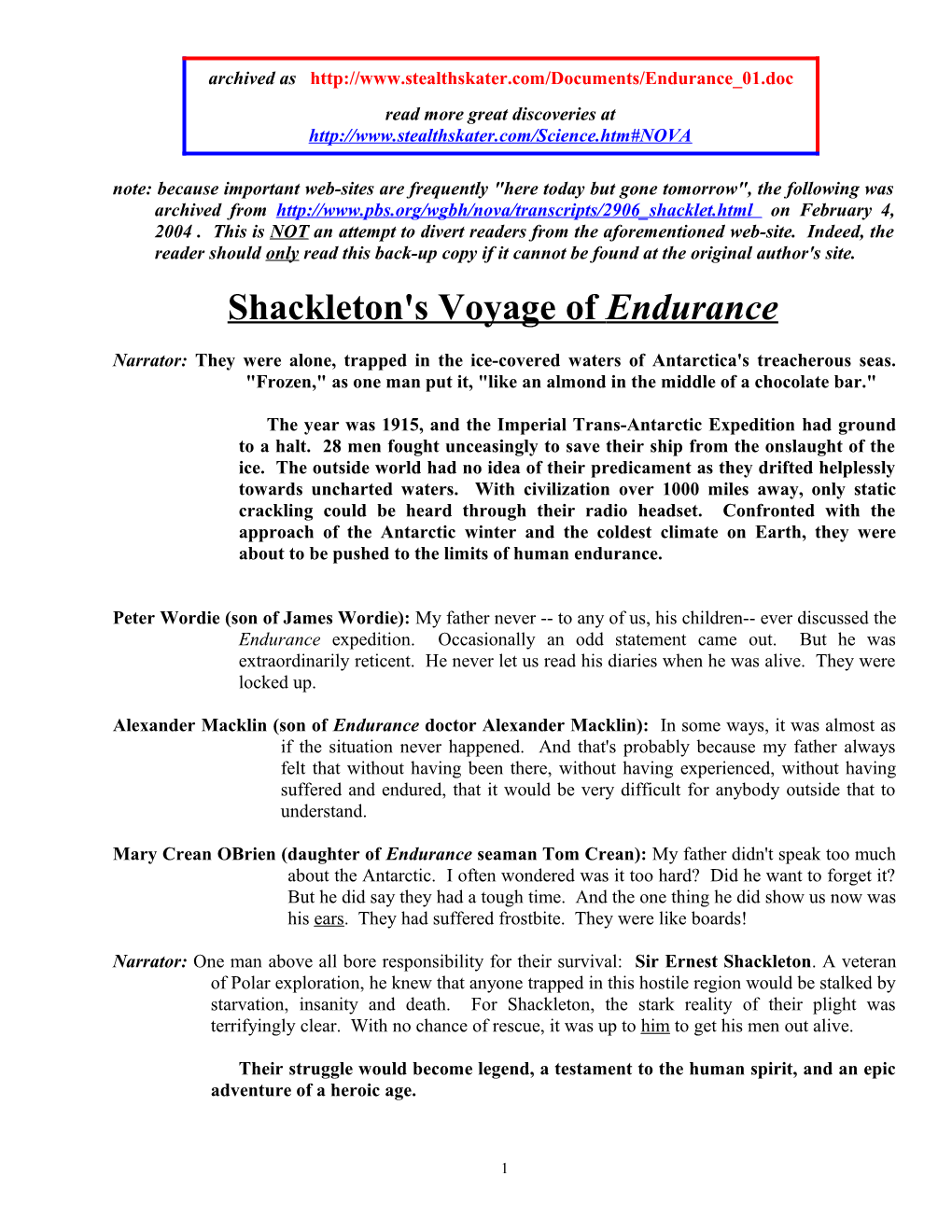

(left-to-right) Top Row: Ernest Holness (stoker), William Bakewell (seaman) 3rd Row: Henry McNeish (carpenter), Reginald James (physicist), Frank Wild (Second-in- Command), Frank Worsley (Captain), William Stephenson (stoker), Herberht Hudson (navigator), Walter Howe (seaman), Charles Green (cook) 2nd Row: Alfred Cheetham (Third Officer), Tom Crean (Second Officer), Leonard Hussey (meteorologist), Lionel Greenstreet (First Officer), Sir Ernest Shackleton (Expedition Leader), Sir Daniel Gooch, Louis Rickinson (engineer), Frank Hurley (photographer) Bottom Row: Robert Clark (biologist), James Wordie (geologist), Alexander Macklin (surgeon), George Marston (artist), James McIlroy (surgeon) Missing from photo: Thomas Orde-Lees (ski expert and storekeeper), Perce Blackborow (steward), John Vincent (boatswain), Alfred Kerr (engineer), Timothy McCarthy (seaman), Thomas McLeod (seaman)

Narrator: From England, the Endurance crossed the Atlantic to Buenos Aires then headed towards Antarctica. Within days, she entered the notoriously stormy waters of the Southern Ocean.

Expedition photographer Frank Hurley -- who had previously filmed in the region -- described the Endurance's passage through the winds known as the "Roaring Forties":

Frank Hurley {voiceover}: For a week, he has flung magnificent power at our starboard quarter but -- beyond an occasional monster leaping aboard to flood our decks -- we have ambled buoyantly South, flung from side-to-side.

Narrator: On November 5th, the towering ranges of South Georgia -- a sub-Antarctic island -- came into view. The Endurance dropped anchor in Grytviken -- a dingy whaling station surrounded by snow-capped mountains. It was the peak of the whaling season and 300 men worked the station, stripping blubber off the carcasses.

Tim Carr (Curator, South Georgia Whaling Museum): When Shackleton arrived at Grytviken, whale catchers were coming in with their catches. And they're saying there's a lot of ice

4 around. And this appeared to them to be a reasonably bad year for ice. This was a bit of a warning to him, and they were prepared to wait a little bit for the ice to open up.

Narrator: The days in South Georgia passed pleasantly as the men roamed the island, discovering its magnificent wildlife and scenery. Frank Hurley enlisted help to haul equipment up a nearby mountain to photograph the Endurance at harbor. He was -- according to one man -- "a warrior with his camera who'd do anything to get a picture."

Shackleton spent time with local whalers learning about Antarctica's ice-ridden Weddell Sea, infamous for crushing ships. By the end of December, he hoped to reach Vahsel Bay -- a landing point that gave him the shortest route across Antarctica. From here, he would sledge inland with five men-and-dog teams in a desperate race to reach the other side before the Polar winter arrived.

Sir Ranulph Fiennes (explorer and author): If you want to try and cross the whole inland plateau -- which is bigger than China -- you only have a very short period of time when human beings can travel -- between November and March to get from 'A' to 'B' -- if you're going to survive. If you overstayed or you set out too early, you'd almost certainly be killed by the cold.

Narrator: With the Southern summer warming South Georgia and war engulfing Europe, Shackleton grew desperate to depart. He could only pray the ice would not impede them.

Richard Hudson (son): I have here a letter which my father wrote to his father, dated from South Georgia on the 2nd of December 1914. It says, "Dear old Dad, just a line before we sail. This is the last port before the South. We have had a very good time so far, and I think we shall do well. I hope to be home again within 19 months and -- if I can manage it -- go straight to the front. What a glorious age we live in."

Narrator: As South Georgia disappeared, Alexander Macklin -- the ship's doctor -- observed,

Alexander Macklin {voiceover}: We had now cut ourselves adrift from civilization and were making our way off the map. We met several large 'bergs drifting majestically North and -- in contrast to their absolute whiteness -- the sea had a dark black look.

Narrator: But Shackleton watched with alarm. As they encountered stream ice, he ordered the sails taken in and proceeded cautiously under steam. Checking the Noon latitude, he was shocked to find ice so far North and knew it meant delays.

Orde-Lees -- a captain in the military -- described their enemy:

Colonel Orde-Lees {voiceover}: This, then, is the pack -- a sight worth coming so far to see. And even as I write, the book is constantly being jerked from under my pen as the ship takes the shock of charging each slab. And we go along scrunch, scrunch through the pack.

Tim Carr: To go through those large blocks of ice in a wooden ship is a pretty horrendous experience. It feels as if the boat is being hammered by heavy objects and the noise is severe. You think the boat is really being punished.

5 Ranulph Fiennes: You need to know what sort of bang was an alarming one and what was just normal. Because a lot of ships who behave wrongly in that sort of pack ice go down terribly quickly.

Narrator: To battle the ice, the Endurance was sheathed in greenheart -- one of the toughest woods available. Shackleton tried to avoid direct hits, scanning the horizon for patches of open water. He shouted orders to the captain (Frank Worsley) who in turn directed the man at the wheel.

In contrast to Shackleton's caution, Macklin noticed …

Alexander Macklin: Worsley specialized in ramming. And I have a sneaking suspicion that he often went out of his way to find a nice piece of floe at which he could drive at full speed and cut in two. He loved to feel the shock, the riding up, and the sensations as the ice gave and we drove through.

Narrator: For weeks the Endurance fought her way through the ice-locked sea consuming her precious supply of coal.

Finally, Orde-Lees observed,

Colonel Orde-Lees: 'Dame Fortune' -- Sir Ernest's old and constant friend -- again favored us. For a rift appeared southward and we passed through.

Narrator: On New Year's Eve, Frank Hurley's diary reflected the hopefulness that had settled over the ship:

Frank Hurley: About Midnight, we crossed the Antarctic Circle with a glorious sunset reflecting in placid waters, and so entered geographic Antarctica with the dawn of the New Year.

Narrator: Below him stood Shackleton, relieved to see open waters. He knew the Endurance could forge ahead with 24 hours of summer daylight to guide her.

Ernest Shackleton: The run southward in blue water with the miles falling away behind us was a joyful experience after the long struggle through the ice lanes.

Narrator: 9 days later, the Endurance drew near to the coast of Antarctica -- a solid wall of ice with cliffs reaching over 100 feet.

Macklin was amazed:

Alexander Macklin: It was an awe-inspiring sight. And radiating from its surface an intense cold could be felt.

Narrator: By January 18th, Shackleton was only a day's sail from his landing point in Vahsel Bay. Once again, he was confronted by the pack. With the promise of open water just beyond its grip, Shackleton decided to enter.

Slowly he realized this was a more dangerous type of ice. The soft, snowy floes began to harden around the ship like concrete. Unable to push through without drastically depleting their fuel, Shackleton made a fateful decision. They would stand still and wait. 6 The next day Frank Wild -- Shackleton's second-in-command -- described their predicament:

Frank Wild {voiceover}: We were so firmly enclosed by the pack that no movement was possible. And from the masthead, not a sign of open water could be seen. Shackleton was of course disappointed, but still optimistic about being able to get free.

Narrator: With land 30 miles to the South, Shackleton considered walking over the frozen ocean to launch his Antarctic crossing. But Summer was half over, and time was against him …

Ranulph Fiennes: ...because just trying to cross 20 miles of loose sea ice with full sledges could take a month. And when he got over that sea ice, he'd be starting a vastly formidable journey in a bad state. But he did know that if he just stayed on the ship, they might get back out and have a good chance of continuing.

Narrator: Confident in the man they called "the Boss", the crew patiently waited, hopeful that a change in wind would soon shatter the pack's grip.

4 newborn puppies provided the men with a welcomed distraction. Irish sailor Tom Crean nursed them like a father. According to Worsley, "everything that was missing in the eatable line was stolen by Crean for the pups."

Peter Wordie: From the diaries, it would appear that they were all made by Shackleton to get on with the daily routine, which obviously had the effect of keeping morale up. And I think Shackleton himself -- with his Irish background and ability to communicate and join in -- made everybody feel that they were one. It was a team and not a "them and us" situation.

Narrator: As the delay dragged on, the men hunted seals and penguins to supplement their provisions. With temperatures plummeting to minus-30 degrees, the meat froze immediately.

Since the sailors had little to do, biologist Bobby Clark engaged them to pull up his wire dredge from the ocean floor, 3000 feet below. Noticing Clark's excitement when he discovered something, the men tricked him by slipping strands of spaghetti into his container.

Although Shackleton had no great interest in the work of the scientists, they had helped him to raise money by making his expedition respectable. Despite differences in rank and background, he insisted that everyone share equally in the burden of ship's chores.

Alexander Macklin: Although Shackleton had gathered a number of specialists around him, many of these specialists were required to undertake tasks that were wholly out with their previous experience. Here was my father -- a newly qualified surgeon, signed on in order for his medical skills -- suddenly finding himself assigned to being a dog-team leader.

Narrator: With no experienced dog trainer on board, Shackleton chose the men crossing the continent with him to learn how to drive the teams. Frank Wild and his beloved husky "Soldier" would train one group. Hurley got "Shakespeare" (the "Holy Hound") who he praised as "a magnificent animal" that "as a companion was better than some humans." 7 As the men struggled with the traces and yelled confusing commands, Shackleton looked on, perhaps wondering if they could possibly survive the trans-Antarctic crossing with its treacherous crevasses and weather.

He asked Orde-Lees to try out the motorized tractor. Brought to pull supplies across the continent, it had never been tested in below-zero temperatures. Ironically, it was easier to pull it than drive it.

Increasingly anxious about their plight, Orde-Lees -- with his military background -- begged Shackleton to let him manage their limited food supplies.

Julian Ayer: You know he was the only serving officer. And here were these -- as he saw it -- a bunch of amateurs, sailing down to the Antarctic, consuming the stores as though they had no care in the World. And he made his views known on the way down. And then later on seeing this profligate crew, he made it his business to kind of squirrel away food. Just in case. Now, of course, if you're a soldier, you do have a feeling about life and death, and you have a worst-case principle of management. The lives of your men depend on an officer thinking these things in advance. Shackleton came from a wholly different school.

Colonel Orde-Lees: He was one of the greatest optimists living...

Narrator: ...observed Orde-Lees in his diary. But he later noted,

Colonel Orde-Lees: Optimism so often raises false hopes that causes disappointment.

Narrator: On Valentine's Day, open water appeared 600 yards ahead of the ship. With no dynamite to blast their way through, Shackleton ordered everyone out with saws and picks to carve a channel through the pack. Frank Hurley captured their struggle on film.

For 48 hours, they worked unceasingly. But as fast as they broke the ice, the pool of open water surrounding the ship froze over. The Endurance couldn't batter her way through. From the deck, Shackleton surveyed the 400 yards of ice -- 10 feet thick -- still blocking the ship … and accepted defeat.

Macklin recalled,

Alexander Macklin: Shackleton at this time showed one of his sparks of real greatness. He did not rage at all or show outwardly the slightest sign of disappointment. He told us simply-and-calmly that we must winter in the pack; explained its dangers and possibilities; and never lost his optimism.

Roland Huntford: He realized at that moment he was not going to be able to cross the Continent. So, although in his heart of hearts he knew the game was up, nonetheless he had the quality of leadership. He could hide his feelings and thoughts from his companions. And he presented to them the mask that he wanted to present. And nobody grasped what was going on because at that point, he had to keep up their morale up. And that involved keeping up the pretense that the expedition could go on, because there is nothing that can crush a man as to see his dreams crumble to the dust. 8 Narrator: In May, the Sun sank below the horizon and the long Antarctic Winter began. Shackleton was haunted by the knowledge that men on earlier expeditions had been driven mad by months of perpetual darkness. Worried that disheveled appearances were a sign of low morale, he insisted that everyone crop their hair.

The carpenter McNeish observed …

Chippy McNeish {voiceover}: We look the lot of convicts, and we are not much short of that life at present. But we're still hoping to get back to civilization someday.

Narrator: As the harsh weather descended the men settled into their winterized quarters (nicknamed "the Ritz."), Leonard Hussey, the meteorologist, amused the men with his banjo. Hurley gave weekly lantern shows, flickering images of past travels across a makeshift screen. Saturday evenings ended with the weekly toast "to our wives and sweethearts" followed quickly by the chorus "may they never meet".

On Sundays, the gang listened to records on a hand-cranked gramophone. Among the recordings was Sir Ernest's account of his last attempt to reach the South Pole in 1909:

[recording of Shackleton voice]: We retraced our steps over crevasses, through soft snow, encountering blizzards, and eventually -- on the first of March -- we arrived at winter quarters.

Narrator: Orde-lees reflected …

Colonel Orde-Lees: We seem to be a wonderfully happy family. But I think Sir Ernest is the real secret of our unanimity. Considering our divergent aims and difference of station, it is surprising how few differences of opinion occur.

Narrator: Nonetheless, friction lurked beneath the surface. The costume parties and musical evenings prompted McNeish to complain,

Chiipy McNeish: We have never had a religious service but plenty of filthy remarks, as there are few who can speak of anything else.

Narrator: Orde-Lees, in turn, found the carpenter to be a perfect pig:

Colonel Orde-Lees: I sit at the same table as McNeish because I thought a little "unrefined" company would be good training for hut life. But McNeish is a tough proposition. First he sucks his teeth loudly, then he produces a match and proceeds to perform various dental operations.

Narrator: The tension of the polar nights was sometimes broken by fantastic displays of the Southern Lights, reminding Shackleton of the natural forces surrounding them.

Ernest Shackleton: We seem to be drifting helplessly in a strange world of unreality. It is reassuring to feel the ship beneath one's feet.

9 Narrator: Since her entrapment the Endurance had drifted with the pack over 600 miles through uncharted waters. Worsley carefully checked the altitude of the stars to plot their meandering course towards the North.

On June 8th, McNeish confided in his diary …

Chippy McNeish: We have drifted 12 miles nearer home. And the Lord be thanked for that much as I am about sick of the whole thing.

Narrator: Imprisoned by the ice, their fate lay in the hands of the winds and currents.

Arnold Gordon (Oceanographer, Columbia University): The drift of the pack ice varies with the strength of the wind. When the wind is blowing strong, the ice is moving rapidly to the North. Of course, when the wind is blowing strong, that's usually when you have a blizzard. But at least you knew at this time when the winds were strong and to the North, that the ice was moving rapidly to the North and eventually will take you out of this.

Narrator: As Winter receded, Worsley described how the darkness gave way to twilight …

Frank Worsely {voiceover}: Every day, we see the glowing colors painted by the Sun. Every day, they last a little longer and stretch a little further.

Narrator: Ironically, as Spring's thaw approached, blizzards became more frequent. One of the worst hit in mid-July with winds blowing over 70 mph. Its force carved grooves and channels into the pack, scouring ice off the surface and enveloping the ship like a sandstorm.

As the wind howled in the rigging Shackleton warned Worsley,

Ernest Shackleton: The ship can't live in this, Skipper. It is only a matter of time. What the ice gets, the ice keeps.

Narrator: When the blizzard subsided, the surrounding pack appeared to Worsley …

Frank Worsley: ...disturbed by the tossing of a mighty giant below. Huge blocks of ice were piled up in wild and threatening confusion.

Narrator: The breakup of the pack had finally begun as winds and currents created conflicting forces of pressure, shaking the frozen sea to life.

Ranulph Fiennes: When 2 ice floes meet together under pressure, the leading edges bust. Then with continued pressure, they get forced up in between the 2 floes -- up to even 30-feet high! These big walls -- or pressure ridges -- act like an enormous sail on a yacht. And the wind can shift these million tons of floes, cracking the pack.

Narrator: According to Worsley …

Frank Worsley: The noise was like an enormous train with squeaky axles. And underfoot, the moans and groans of damned souls in torment.

10 Tim Carr: They were lying in their bunks listening to this noise day-and-night. And not only just listening to it, it was getting worse-and-worse because the pressure was building up from storms from all around parts of the Weddell Sea pushing these ridges, and pushing against the Endurance. And parts of the boat were actually starting to come apart. Some of the rigging was falling on deck. She would get jolts and thunders. I would imagine these men were really beginning to fear for their lives.

Narrator: The crew struggled daily to prevent the pressure of the ice from damaging the Endurance. Then in October -- the Antarctic Spring -- the floe beneath her bow broke in two. Shackleton examined the crack, hopeful the ice might release them.

Over the next few hours, water surrounded the hull. Since there wasn't enough time to start the engines, the men hoisted the sails. But the Endurance was held fast. The next day, the lead of open water froze over.

Arnold Gordon: Many ships are designed to survive the pressures of the pack ice. These ships have a round bottom; as the pressure grows the ship is lifted up out of the ice. The Endurance was not such a ship. While it did have some ice-strength capabilities, the pressure that the ice would exert on the hull would crush it rather than move it up out of the ice.

Narrator: From the deck, the crew watched apprehensively as enormous blocks of ice churned over each day and ground through the floes.

Seaman Walter Howe recalled the assault on the Endurance in a radio interview 40 years later:

[archival audio of Walter Howe]: Well, the ice got her under the starboard quarter and lifted her bodily -- as it were -- and threw her forward. And then she listed very heavily to port and the timbers began to crack and groan. It was there like heavy fireworks and blasting of guns.

Narrator: As Shackleton surveyed the damage, he appeared astonishingly calm. His determined optimism defied the impending sense of doom. 11 Roland Huntford: To the outside, he presented the appearance of complete self-control, indifference, almost casualness. And this was very calculated because at every turn, his great trouble --his enemy --was not the ice but his own people in the sense that it was their morale. That was the foe. He had to prevent their morale from crumbling.

Narrator: Throughout the night, McNeish the carpenter struggled to repair the broken ship.

As water poured in, Orde-Lees helped man the pumps …

Colonel Orde-Lees: We were just able to keep pace with the leakage. Down aft, one could hear the ominous sound of the in-rushing water. Our little ship was hopelessly crushed and helpless among the engulfing ice.

Narrator: At 9:00 pm, Shackleton ordered the lifeboats lowered to the floe.

Seaman Walter Howe remembered the moment …

[archival audio of Walter Howe]: He sent Frank Wild along forward to our quarters, who explained to us that it was a case of "get out" and to pack our bags with all necessary equipment we required and to be prepared for any emergency.

Narrator: The dawn of October 27th was -- according to Shackleton -- "a fateful day".

Ernest Shackleton: Though we have been compelled to abandon the ship -- which is crushed beyond all hope -- we are alive and have stores and equipment for the task that lies before us. I pray to God that I can manage to get the whole party to civilization.

Narrator: As men and dogs struggled onto the ice, Orde-Lees expressed their shock …

Colonel Orde-Lees: For the first time we realized that we were face-to-face with one of the gravest disasters that can befall a polar expedition. For the first time, it came home to us that we were wrecked!

John Blackborow (grandson of Endurance seaman Alexander Macklin): You've got to remember, a sailor is a sailor and that's his ship -- his home. And once he's off that ship, he's at a loss. So once the ship had gone, my grandfather -- I know -- felt not at ease on the ice.

Narrator: Macklin wrote …

Alexander Macklin: It must have been a moment of bitter disappointment to Shackleton. But as always with him, what had happened had happened without emotion, melodrama, or excitement. He said, "Ship and stores have gone, so now we'll go home."

Roland Huntford: Extricating yourself from defeat is a strain that has broken many a man. It did not break Shackleton. He simply adapted to the new situation, and he realized "If the

12 one goal had disappeared, we'll have another one. And so if I can't cross the Continent, I'm going to bring all my men back alive."

Because you mustn't forget that Polar exploration was littered with dead bodies. And so he felt "What I will do is I will bring all my men back alive." It was his version of the old saying of "snatching victory from the jaws of defeat".

Narrator: Not anticipating disaster, Shackleton had brought only 5 small tents that would now have to shelter 28 men. To make matters worse, there were only 18 sleeping bags made with reindeer fur. Shackleton had the men draw lots to see who would have to make do with woolen blanket bags.

Jonathan Shackleton: But he "rigged it" so that he and a couple of the other leaders didn't get the best bags. Members of the crew, seamen got the best bags. That was a very big decision because it might have been a life-or-death decision for Shackleton and his other officers.

Narrator: Shackleton then assigned the men to their tents. He chose the most difficult individuals to be with him.

Alexandra Shackleton (granddaughter of Ernest Shackleton): Enmities can be sometimes extremely destructive to the harmony of an expedition. And so can alliances. So he moved people around and noticed how people were getting on with each other -or- not getting on with each other. But it was all based on knowing his men. It's no good knowing theoretically how to handle people if you don't really notice what people are like. And he was extremely observant.

Narrator: At dawn, Shackleton called the men to discuss his plan. They would march toward either Snow Hill or Paulet Island, where he knew supplies had been left by shipwrecked mariners. From there, he would lead a small party down the peninsula to seek help from whalers known to hunt in Wilhelmina Bay.

Because the boats on sledges weighed over a ton apiece, they were too heavy for the dogs to pull and would have to be man-hauled. Each individual could take only a handful of personal belongings. The puppies would have to be shot. There simply was no extra food to spare.

The next day, 15 men -- harnessed like dogs at the traces -- strained to pull the lifeboats. As the Summer temperature climbed to 25 degrees, they sank into the soft snow. Soaked by sweat and racked by thirst, it was killing work. After 48 hours of excruciating effort, they had covered less than 2 miles. Unable to advance across the frozen ocean, they would have to wait and pray that the drift of the pack would carry them closer to land.

John Blackborow: They were well aware that it could get worse. But at first, their immediate thoughts were survival. And that was to get some shelter and to get some food down them and stabilize themselves. So it's only as time went on that they realized their full predicament. And that was a very depressing time for them all.

Narrator: The men searched for an ice floe that would be safe from the pressure and dubbed it "Ocean Camp". They would have to prepare to live on the ice.

13 A small group returned to the sinking Endurance to salvage wood and rigging. McNeish, the carpenter, wanted to build a smaller boat from the wreckage but was overruled by Shackleton. Frank Hurley proposed sawing through the deck to salvage stores from the flooded hold. It was risky work, but Shackleton agreed.

Then Hurley risked his life to rescue his treasured negatives.

Antoinette Hurley Mooy (daughter of Endurance photographer Frank Hurley): Now, when he rescued all those things from the ship, Shackleton appeared on the scene. And he wasn't at all happy about that -- going down in the waters to rescue all those things. But without all tha,t there would have been no film of the Shackleton expedition.

Narrator: Since most of Hurley's negatives were glass plates, they were too heavy to bring on the lifeboats. Shackleton helped him select 150 of the best. But despite Hurley's dismay, 400 would be left behind.

Antoinette Hurley Mooy: Shackleton did not like anybody going against him, and a whole lot of those plates had to be smashed. And Shackleton stood by Dad while he smashed them because I'm darned sure Shackleton would have known that Dad would have sneaked them aboard somehow.

Narrator: On November 21, 1915, the Endurance finally sank beneath the ice. Her valiant struggle was immortalized in Hurley's images.

Shackleton simply entered in his diary …

Ernest Shackleton: At 5 pm, she went down. The stern was the last to go under water. I cannot write about it.

Narrator: After 2 months adrift on the ice, morale was crumbling. Shackleton decided to make a second attempt to march towards land.

Macklin described the desperate conditions …

Alexander Macklin: The surface would not stand the drivers' weight. And running beside the sledge was terribly hard work. But the dog drivers went ahead carrying picks and shovels and making the road so that the boats could be brought steadily forward.

Tom McNeish: When they were pulling the boats in the sledges, Chippy was ill. He was ridged with piles, and the man was in agony. The whole lot of them were in agony.

Narrator: To McNeish -- the carpenter -- the inhumane march seemed an extraordinary expenditure of effort for little gain. Demoralized and exhausted, he was losing faith that Shackleton knew how to save them. Suddenly, he refused to obey orders or march any farther.

Peter Wordie: And he pleaded that since they had lost the ship Endurance, no longer did ship's articles and discipline apply on the ice. Shackleton rightly said that the discipline went on regardless of whether the Endurance was lost or not.

14 Tom McNeish: Chippy was a man. Be didn't like being told what to do. If Chippy didn't like it, Chippy would tell you. This is the kind of man he was. Authority meant nothing to him.

Roland Huntford: Shackleton had to quash this immediately, because there was a hidden danger here that the carpenter was voicing the opinions of 2-or-3 other members of the crew. And more for all we know. And no leader -- particularly on the edge of survival -- can tolerate the least threat to his authority.

Narrator: Confronted with the possible disintegration of the entire group, Shackleton gave a persuasive performance. He insisted he was not only the leader of the expedition but also its lawful master. Wages would be paid regardless of circumstance; disobedience swiftly punished. They would only survive as a team. Reluctantly, McNeish backed down.

Alexandra Shackleton: In his diary, my grandfather referred to it obliquely, saying, "I shall never forgive the carpenter in this time of storm and stress." You see, he demanded total loyalty from his men. And he offered total loyalty in return. It was a reciprocal, very close, important relationship. That's why any discord -- any disobedience -- he took personally.

Narrator: On December 29th, Frank Wild summed up their ordeal …

Frank Wild: After 7 days of the hardest imaginable labor, we were stopped by ice so terribly broken and pressed up that it was impossible to proceed any further. The total result of this killing work was an advance of 7½ miles.

Narrator: Ironically, Worsley's navigational readings showed that the drift of the pack had carried the men further away from land than when they had started. But for Shackleton, the march had served a vital purpose.

Roland Huntford: By proving that it was futile, he showed his men -- beyond a shadow -of-a-doubt -- that he had tried everything he possibly could and therefore there could be no reproaches afterwards. And this was vital not only to ensure obedience to orders, but also to keep up morale.

Narrator: On New Year's Eve, Hurley captured the regret that hung over the cluster of tents named "Patience Camp".

Frank Hurley: Our present position one cannot altogether regard as "sweet", drifting about on an ice floe 189 miles from the nearest known land. Still -- to apply our old sledging motto -- "it might be much worse".

Narrator: Hurley -- who had been appointed to the official post of fire-kindler -- made one New Year's resolution for 1916: "One match, one meal."

Food became the men's only comfort. For some, it was an obsession. Only 10 weeks' supply of flour was left along with 3 months of sledging rations. To bolster their dwindling food supply, Shackleton ordered seals and penguins to be hunted daily. Anticipating their eventual migration, Orde-Lees urged Shackleton to stockpile meat for the approaching Winter. He refused.

15 As can be seen in the photograph, one of the most remarkable aspects of Frank Hurley's images of the Endurance expedition is the seeming serenity apparent in the faces and scenes he caught on film. Yet the perils of surviving on sea ice hundreds- of-miles from civilization through the long, dark, bone-numbingly cold Antarctic winter are as rife as squawks in a penguin rookery … and the men of Endurance knew it.

Julian Ayer: My grandfather thought -- as a military man -- that it was important to have supplies. And the famous statement that the "army marches on its stomach", that seemed to him to be elementary. And I think he regarded ... you know … Shackleton was a "PR" man as far as my grandfather was concerned. He raised the cash, but there was a shallowness about Shackleton that my grandfather would have found difficult to handle.

Roland Huntford: If you start stockpiling food, it would mean that there was disaster ahead and they were having to prepare for some awful eventuality. And Shackleton realized this would have produced mental strain which probably would have led to insanity. And faced between starvation and insanity, Shackleton chose starvation as the lesser evil.

Narrator: Rather than stockpile food, Shackleton ordered the dogs shot. They consumed a seal a day, whereas 28 men could feed off one animal for a week. The teams were no longer needed -- sledging toward land was impossible.

Frank Wild recalled …

Frank Wild: This duty fell upon me. And it was the worst job I ever had in my life! I have known men I would rather shoot than the worst of dogs.

Narrator: Hurley found it …

Frank Hurley: ...a sad unfortunate necessity. Hail to thee, old Shakespeare. I shall ever remember thee: fearless, faithful, and diligent.

Narrator: When the killing was over, Macklin grieved …

Alexander Macklin: I cut them up and dressed some of them for eating. Poor wretches, they had no idea what they were in for and drove gaily up to the scene of their execution.

16 Narrator: As the days dragged on, Shackleton scribbled in his diary …

Ernest Shackleton: Please God, we will soon get ashore.

Narrator: For 3 months, "Patience Camp: drifted North with the pack, beyond the reach of the Antarctic Peninsula. As they approached the edge of the Weddell Sea, Shackleton knew their floe would soon break apart. He plotted their escape. Powerful winds and currents would drive their lifeboats northward where their last chance of landfall was Clarence or Elephant Island. But if they missed this refuge of rock and ice, they faced being swept into the treacherous Southern Ocean where survival was almost impossible.

As waves rolled in from the North, the ice moved up-and-down, breaking the floes apart. Shackleton kept a 24-hour watch, ready to launch the boats when the pack opened up.

Arnold Gordon: And it becomes a very dangerous situation because the ice is breaking up. It's moving apart and together very rapidly with the waves as they penetrate the ice. And exactly when to put the boats in the water … If you put them in too early -- into a lead -- then the ice just closes right up and crushes the boats and you'd be in big trouble. If you stay too long on the ice floe, you might not have enough time to prepare the boats to put into the water. So the timing was very important.

Narrator -: On April 9th after 14 months of imprisonment by the ice, the chance to save themselves had finally arrived. But first they would have to escape the grip of the pack.

Seaman William Bakewell remembered …

William Bakewell: Our first day in the water was one of the coldest and most dangerous of the expedition. It was a hard race to keep our boats in the open leads. We had many narrow escapes from being crushed.

Narrator: Nothing in their experience had prepared the men for the ordeal to come.

Roland Huntford (historian and author): First of all, for months-and-months on end these men on the ice had been virtually "landlubbers". And most of them were certainly not small- boat people. But there they were expected to maneuver open boats. As if that were not enough, they were asked to cope with the most difficult, the most dangerous conditions on the surface of the Earth, on the surface of the sea.

Narrator: The first 2 nights, Shackleton scanned the heaving ice for a stable floe where he could rest his demoralized crew. Their desperate searching was etched indelibly in artist George Marston's memory.

Relief was fleeting. The men laid awake to the sounds of the ice cracking under the tents and killer whales circling in the darkness. Thereafter they stayed in the boats.

As Frank Hurley recalled …

Frank Hurley: Several tried to snatch sleep, but most preferred rowing to lessen the pangs of shivering. Everyone was wet and achingly cold.

17 Peter Wordie (son of Endurance scientist James Wordie): At the end of the period on the oars, your hands had to be actually chipped off the oars. It's very hard to imagine when you get down into a boat after being rowing, your hands are blocks of ice.

Narrator: A constant gnawing hunger took hold as the meager rations dwindled.

Peter Wordie: There was no food. They had one ship's biscuit-a-day which as my father said, "We looked at for breakfast, we sucked it for lunch, and we ate it for dinner." Thirst was a problem. And I think it was during that boat journey that they chewed leather in order to keep their saliva going.

Narrator: On the 4th day of the journey, Frank Worsley was at last able to determine their position. The boats were 30 miles East of "Patience Camp". Treacherous currents were dragging them into the open ocean.

Shackleton faced an agonizing decision. To retreat to the possible shelter of the Peninsula. Or defy the currents in a risky bid for Elephant Island. Shackleton doubted the men could hold out much longer.

Alexandra Shackleton (granddaughter of Ernest Shackleton): Ernest Shackleton knew that a man can be deprived of 2 out of the 3 essentials -- the essentials being food, water, and sleep. But not all three. After that, he will not last very long.

Narrator: Shackleton thought …

Ernest Shackleton: Most of the men were now looking seriously worn and strained. Their lips were cracked. And their eyes and eyelids showed red in their salt-encrusted faces. I decided to run for Elephant Island.

Narrator: As night fell, they seemed no closer to land. Shackleton sensed several men slipping away.

Ernest Shackleton: In the momentary light, I could see the ghostly faces. I doubted if all the men would survive the night.

Narrator: At dawn, Frank Wild saw that the men were alive. But their will to fight the seas was foundering.

Frank Wild: At least half the party were insane. Fortunately not violent, simply helpless and hopeless.

Narrator: In the endless vista of sea and ice, Shackleton strained for a glimpse of land when suddenly in the distance …

Ernest Shackleton: ... Elephant Island showed cold and severe in the full daylight.

Narrator: Worsley had been sleepless at the helm for over 80 hours. Now he steered the little fleet resolutely toward the mist-bound island. Finally on the 7th day at sea, the 3 boats plunged into the surging waters of the island. Worsley searched the coast for a safe landing place.

Frank Worsley: All this time, we were coasting along beneath towering rocky cliffs and sheer glacier faces, which offered not the slightest possibility of landing anywhere. At 9:30 am,

18 we spied a narrow rocky beach at the base of some very high crags and cliffs. And we made for it.

Narrator: Shackleton urged them on as the boats were swept into shore. Then the men set foot on land for the first time in 16 months. Hurley captured the long-awaited moment with his pocket camera.

Worsley described their elation as they hauled the boats onto the beach …

Frank Worsley: Some of our men were almost light-headed as well as light-hearted. When they landed they reeled about, laughing uproariously.

Narrator: Their joy spiraled out-of-control as scientist James Wordie watched helplessly …

James Wordie: Some fellows, moreover, were half-crazy. One got an axe ...

Peter Wordie: In his diary, my father described an extraordinary scene of killing seals. Slaughter for slaughter's sake -- a behavior which in many cases could be described merely as insane.

Shackleton let them do this. He didn't stop them immediately. And then obviously he managed to restore a discipline and order into the situation. That once more shows his power of keeping people together.

Narrator: Gratefully, the ravenous men ate their first hot meal in 5 days. Then Shackleton let them sleep.

Ernest Shackleton: I decided not to share with the men the knowledge of the uncertainties of our situation until they had enjoyed rest, untroubled by the thought that at any minute they might be called to face peril again.

Roland Huntford: Now when Shackleton and his men landed on Elephant Island, they'd come to another crisis. Shackleton had saved his men in the sense he'd got them all alive out of the ice and onto terra firma. But now -- how to get back to civilization?

Ernest Shackleton: There was no chance at all of any search being made for us on Elephant Island. Privation and exposure had left their mark on the party. The health and mental condition of several men were causing me serious anxiety. A boat journey in search of relief was necessary. That conclusion was forced upon me.

Narrator: Elephant Island was far from any shipping route. The nearest outpost of civilization was near the tip of South America -- 400 miles from Elephant Island. But the prevailing winds and currents would prevent the boat from getting there.

Shackleton's audacious new plan was to sail 800 miles Northeast to South Georgia where the voyage of the Endurance began.

Roland Huntford: Now, Shackleton realized that there were very few people who could survive an open boat journey of that length because several men just about didn't survived the short journey from the ice. 19 Narrator: There was no other choice. Faced with survival here, some lost the will to live. Their bodies were blighted by frostbite and open sores. None were fit for such a voyage.

Ernest Shackleton: All hands knew that the perils of the proposed journey were extreme. I called the men together, explained my plan, and asked for volunteers. Many came forward at once.

Narrator: Captain Frank Worsley, who had cut his teeth navigating small boats in storm-tossed waters; second officer Tom Crean, a tough veteran of 2 Polar expeditions; able seaman Tim McCarthy proved his mettle on the boat journey to Elephant Island; a troublesome bully on land; and John Vincent appeared indestructible at sea. Mutineer Chippy McNeish was also an unlikely choice -- plagued by rheumatism -- but Shackleton counted on the rebellious carpenter to make the largest boat seaworthy for their voyage.

Roland Huntford: The most important man onboard ship is not the captain or the navigator. It's the shipwright, because he's the man who keeps her afloat and makes her able to stand the fury of the ocean. He was one of the very few people alive, probably, who could have prepared her for the strains and buffeting of an oceanic voyage.

Narrator: With ingenuity and scavenged parts, McNeish raised her sides, covered her with a canvas deck, and filled the seams with Marston's oil paints and seal's blood.

On April 23rd, Shackleton gave orders to ready the James Caird for launch, leaving Frank Wild in charge:

Ernest Shackleton: The 20-foot boat had never looked big. She appeared to have shrunk in some mysterious way. I had a last word with Wild. I told him I trusted the party to him and said good-bye.

The men who were staying behind made a pathetic little group on the beach. But they waved to us and gave 3 hearty cheers. Then we pushed off for the last time and within a few minutes, I was aboard the James Caird.

Tim Carr (Curator, South Georgia Whaling Museum): So they left Elephant Island -- probably all of them with about as much hope as nothing to get to South Georgia. They couldn't have thought they had much chance in doing it. But what else could they do? They had to do it. They had to go. They had to try!

Narrator: Shackleton left behind a farewell letter …

Ernest Shackleton: "In the event of my not surviving the boat journey, you can convey my love to my people and say I tried my best."

Narrator: The crew raised sail, hoping that fair weather and brisk winds would carry the Caird to South Georgia. It was the navigational equivalent of finding "a needle in a haystack".

Worsley manned the first watch with Shackleton …

Frank Worsley: We held her North by the stars. While I steered with Shackleton's arm thrown over my shoulder, we discussed plans and yarned in low tones. 20 Narrator: But weather in these latitudes is notoriously unstable. The days following brought the freezing gales that Shackleton had dreaded.

Ernest Shackleton: The sub-Antarctic Ocean lived up to its evil winter reputation.

Narrator: 3 seasick men braved the sleet and snow while the others crawled below into the flooded hold to rest. Worsley confessed …

Frank Worsley: More than once when I woke suddenly, I had a ghastly fear that I was buried alive.

Narrator: The gale carried the Caird onward. But Shackleton couldn't be sure where.

Roland Huntford: Although Shackleton was the leader, the man upon whom the technical feasibility of the voyage depended was Worsley because he was the navigator. And if you're sailing 800 miles over the open sea, it's navigation that gets you somewhere.

Narrator: As Worsley estimated, the gales propelled the Caird as much as 50 miles each day. But unless he could determine their latitude and longitude with the aid of a sextant, they could be sailing hundreds-of-miles off course.

Tim Carr: It's cold, and he's going to really try to bring the Sun down to the horizon.

Narrator: Navigating the same Antarctic seas, Tim and Pauline Carr know well the challenges that Worsley faced. The shrouded Sun made it virtually impossible to take an accurate reading.

Tim Carr [on boat]: Captain Frankie Worsley's got his sextant. And he's trying to do his dead reckoning, take his sights. His eyes must have been on the Sun the whole time, waiting for that little ball to come out and pierce through the dank clouds, through the overcast. He's just hoping like mad that there's not going to be a lurch and he's going to get thrown overboard.

Narrator: The violent pitching of the boat could have thrown off his measurement and course by miles.

Tim Carr: He's bringing the Sun down to the horizon … waiting till he gets to the top of a swell … and then shouts "Mark!" down to Shackleton.

Narrator: The sights were just the first step in a complex calculation using trigonometry and nautical tables.

Tim Carr: And then he's got to go down and work out this sight with water & spray all over the place. How can the man do it? I just don't know. He must have been a magician!

Narrator: On the 6th day, the Sun emerged and Worsley's sights revealed the Caird had sailed 238 miles. They were now in the heart of the Southern Ocean.

Shackleton knew that no one had ever survived an open boat journey in these waters:

Ernest Shackleton: We were a tiny speck in the vast vista of the sea. The forces arrayed against us would be almost overwhelming. 21 Narrator: The frail lifeboat was never meant to weather such a voyage. As the Caird plunged into yet another gale, Worsley marveled at the crew's resilience …

Frank Worsley: When I relieved McCarthy at the helm, the seas pouring down our necks. I felt like swearing. Then he informed me with a cheerful grin, "It's a fine day, Sir."

Jonathan Shackleton (cousin of Ernest Shackleton): Tim McCarthy was wonderfully optimistic and was a key member . Shackleton wrote about how much -- how important -- a person he was in that boat journey. He didn't have skill as a navigator. But he kept their spirits up.

Narrator: Shackleton shared a special bond with officer Tom Crean.

Mary Crean O'Brien (daughter of Endurance officer Tom Crean): They were pals as well as workmates. And I suppose they were a good team. They "clicked" in other words -- the two of them.

Narrator: Shackleton would later recall …

Ernest Shackleton: One of the memories that comes to me from those days is of Crean singing at the tiller. He always sang while he was steering. And nobody ever discovered what the song was.

Mary Crean O'Brien: He had a poor voice, only the words of everything. He had a very poor voice.

Narrator: As their drenched clothing froze on their bodies, some of the men faltered. Strapping John Vincent lay petrified in the hold. Chippy McNeish was tormented by his aching legs, but he stubbornly tended to the boat.

Tom McNeish (grandson of Chippy McNeish): There were waves coming at them. 30 feet. At times, it was swamped and it rode through them. And the next minute, it was covered in ice.

And it was getting too heavy with ice on it. She was starting to sink. They had to crawl all over it and break the ice off it to keep her afloat. It must have been horrendous. They must have been terrified.

Narrator: As the storm raged, Shackleton watched over each man with obsessive care.

Roland Huntford: What kept them from cracking on this journey was -- again -- Shackleton's sheer willpower, his leadership, this flame that burns within him. He understood that when men are at the limits of survival, they have to be nursed.

Alexandra Shackleton: He noticed that if any man was particularly unable to cope, he ordered hot milk not just for him but for everyone so this man would not -- as he put it -- have "doubts about himself".

Roland Huntford: And the next minute, he was a martinet driving his men on, always adapting to circumstances.

22 Alexandra Shackleton: And during the agonizing boat journey, Worsley wrote in his diary, "However bad things were, he somehow inspired us with the feeling that he could make things better."

Narrator: The gales relented on the eleventh day. Worsley called it a "day's grace". He watched an albatross soar overhead -- the fabled good omen of mariners …

Frank Worsley: His [the albatross'] poetic motion fascinated us. The ease with which he swept the miles aside filled us with envy. He could have made our whole journey in 10 hours.

Narrator: Worsley's sights revealed that they had sailed 496 miles. Now precision was everything. He adjusted the course for South Georgia. If he erred by just half-a-degree, the Caird would miss the island and sail into the limitless South Atlantic.

The albatross flew alongside the Caird, seeming to speed their passage. The next day, the boat covered a record distance of 96 miles. If Worsley was right, they could be just 2 days from South Georgia. But it seemed like an eternity. The Sun and salt-tainted water stirred a raging thirst.

Worsley was unable to take sights in the overcast. Once again, the Caird plied an uncertain course. Then on the 15th day, seaweed floated on the swells -- a sure sign of land!

With hushed expectation, the men scanned the seas ahead …

Frank Worsley: ... then, half-an-hour past Noon, McCarthy raised the cheerful cry, "Land ho!" The thoughts uppermost were "We've done it!"

Narrator: They had accomplished what many regard as the greatest small boat journey in the World. 800 miles across the stormiest seas on Earth in a 22-foot vessel.

Alexandra Shackleton: It was a colossal achievement. When they saw the black peaks of South Georgia, huge relief and happiness. But the story was not quite over yet.

Narrator: The winds suddenly rose. In their hour of triumph, safety slipped from their grasp. The boat was caught in the fury of hurricane-force winds. Shackleton despaired of ever reaching land …

Ernest Shackleton: The chance of surviving the night -- with the driving gale and the implacable sea forcing us on to the lee shore -- seemed small. I think most of us had a feeling that the end was very near.

Roland Huntford: And this is where Worsley came into his own because he understood the way a sailing ship worked. And so he performed a miracle there. Somehow he clawed his way offshore.

Narrator: Worsley hauled the Caird away from the rocky coast to sit out the gale. By morning, the seas calmed and Shackleton ordered the boat in to shore …

Ernest Shackleton: I stood in the bows directing the steering as we ran through the kelp and made the passage of the reef. In a minute-or-two, we were inside and the James Caird ran in on a swell and touched the beach. 23 Roland Huntford: What got the James Caird to South Georgia was a combination of luck and skill. The skill was Worsley's -- this brilliant navigator, this wonderful small boat handler. But there is always the element of luck. And this is where we come to the great imponderable: Shackleton was a lucky man. He was always lucky.

Narrator: After 17 days at sea, the 6 men stumbled ashore to their long-sought haven. Relieved to be on solid ground, McNeish hobbled up the slope behind the cove.

Chippy McNeish: The Boss and Skipper went away for a walk. I went on top of the hill and had a lay on the grass. It put me in mind of old times at home, sitting on the hillside and looking down at the sea.

Narrator: But they would not rest for long. The Caird had landed on the wrong side of South Georgia. The whaling stations were on the opposite coast.

By sea, Worsley reckoned it to be 150 miles. With the men weak and the Caird battered, it was unthinkable. There was only one alternative: to traverse the island [on foot] to the closest inhabited station. Shackleton knew the risks only too well …

Ernest Shackleton: We had a very scanty knowledge of the conditions of the interior. No man had ever penetrated a mile from the coast of South Georgia. And the whalers, I knew, regarded the country as inaccessible.

Narrator: The mountains and glaciers of the interior would not be mapped or photographed until years later. Shackleton prepared to depart, writing instructions for McNeish …

Ernest Shackleton: "Sir, I am about to try to reach the East Coast of this island for relief of our party. I am leaving you in charge of Vincent, McCarthy, and yourself. You will remain here until relief arrives .in the event of my non-return. Yours faithfully, E.H. Shackleton."

Narrator: But for 10 days, storms made the journey impossible. As Worsley observed, for Shackleton -- the man of ACTION -- waiting was unbearable …

Frank Worsley: Meantime, the strain of waiting and anxiety for his men was telling on him. He was then nearer to depression than I'd ever known him. He said to me, "I'll never take another expedition, Skipper."

Narrator: The fate of the men on Elephant Island weighed heavily on his mind:

Ernest Shackleton: Over on Elephant Island, 22 men were waiting for the relief that we alone could secure for them. Their plight was worse than ours. We must push on somehow.

Narrator: On a narrow spit of land they called "Cape Wild", Shackleton's men recorded their sufferings in their diaries …

Frank Hurley: Life here without a hut and equipment is almost beyond endurance. Such an inhospitable coast I have never before beheld.

24 Alexander Macklin: I think I spent this morning the most unhappy hour of my life. All attempts seemed so hopeless.

Lionel Greenstreet {voiceover}: So passes another goddamn rotten day.

Alexander Macklin: Men sat and cursed this element.

Frank Hurley: I am convinced they would starve or freeze if left to their own resources on this island.

Roland Huntford: The men who remained on Elephant Island, they had to wait. Waiting is always harder than acting. And this is where Frank Wild came into his own. Wild was a rather melancholy character because he had failings. He drank, he never quite "made it" ashore. But he was perfectly suited to holding the men together on Elephant Island. He was used to following orders. And his orders were to keep the men alive.

Narrator: Exposed to the ravages of wind and sea, their prospects on this barren shore were grim. But Wild refused to allow the men to surrender to despair …

Frank WIld: Some of the party had become despondent and were in a "What's the use?" sort of mood. They had to be driven to work. And none too gently, either!

Narrator: The treeless island offered no natural shelter, so Wild mustered the crew to build one. With bleeding, frostbitten hands, they cobbled a ramshackle hut from the 2 lifeboats and scraps of canvas.

The men crowded into these quarters, barely 10 by 19 feet. The frozen ground was coated with penguin guano and the smoking fire burned their eyes. But it shielded them from the elements. Each day, Wild planned a strict regimen of duties to occupy their days.

Alexandra Shackleton: He was aware of the vital importance of a routine. Previous expeditions in the last century meant alcoholism, suicide, and insanity. They were all kept together pretty well … and that's leadership.

Narrator: Wild roused all hands at 9:30 daily for chores and hunting. Penguins supplied food and fuel for the stove. At day's end, they were still busy writing in their diaries, reading aloud, and singing with Hussey on banjo.

Roland Huntford: He did keep them alive. And the reason he kept them alive is because he kept them sane. And he was probably the one man aside from Shackleton who could have achieved that.

Narrator: Most of all, Wild kept hope alive through the days of waiting. The men showed their gratitude in an ode to their leader.

25 My name is Frankie Wild-o. Me hut's on Elephant Isle. The wall's without a single brick And the roof's without a tile. Nevertheless I must confess, By many and many a mile, It's the most palatial dwelling place You'll find on Elephant Isle. It's the most palatial dwelling place You'll find on Elephant Isle.

Narrator: Nearly a month had passed since the Caird left Elephant Island. As the Polar winter approached, pack ice encircled the island. Wild knew that a rescue ship could never break through. Still, every day he ordered his men to pack up and stow …

Frank Wild: Get your things ready, boys. The Boss may come today.

Narrator: But rescue was still remote. Shackleton's trek across the no-man's land of South Georgia was just beginning. With screws in their boot soles for traction, Shackleton, Worsley, and Crean prepared to travel light for speed with only 3 days' food, leaving the tent and sleeping bags behind.

Roland Huntford: The crossing of South Georgia posed almost insuperable difficulties. They didn't have the proper equipment. Their clothes were threadbare. But worse than that, they'd been cooped up on this boat for a fortnight so that they were anything but fit. Their limbs weren't even working properly. It's almost like astronauts coming back to Earth.

Narrator: To find their way, they had only a compass and a map of the island showing nothing more than an outline of the coast. By dawn, the 3 men reached high ground and Shackleton glimpsed the interior for the first time. It was an unnerving sight …

Ernest Shackleton: The interior was tremendously broken. High peaks, impassable cliffs, steep snow- slopes, and sharply descending glaciers were prominent features in all directions.

Narrator: The sheer icy crags in their path rose to nearly 4,000 feet. For 3 weak, malnourished men, it was as daunting as Everest!

Pauline Carr: I can't even begin to feel how it would be for them with just the bare minimum gear that they had. Here we [with Tim] are -- fully equipped with everything -- and I still get scared.

Narrator: Among the few permanent residents of South Georgia, Tim and Pauline Carr have followed in Shackleton's footsteps.

Tim Carr: Well, one of the big problems was that their screws that McNeish had put into the soles of their boots had all-but-worn out. They had to go down this very steep slope by cutting steps. And all they had between them was a ship's carpenter's adz. They'd get a little bit of an edge in there, foot on there, and then a foot in there.

26 And these were tired men. They didn't want to mess around doing that, but it was the only way down.

Narrator: After climbing for 15 grueling hours, Shackleton and his companions left the mountains behind. But a new danger lay ahead. The landscape was a maze of crevasses. One misstep could send them plunging to their deaths.

Tim Carr: Shackleton, Crean, and Worsley immediately saw that they had some crevasses to negotiate and therefore -- they would be something like this one, 50- feet deep -- if one of them fell in one of these crevasses, they probably would have jeopardized their whole crossing.

Narrator: For protection, all they had was a length of fraying rope from the Caird.

Tim Carr: They would have had to have roped up before crossing these glaciers. They would have had their natural fiber alpine rope and took an end of it -- like this -- and got it around their waists. And being nautical as well, they probably would have done a bowline fairly close in to the waist like that -- dependable knot. And then if they had have fallen, they'd just take it right up like that and probably would have been pulled out by the other two. But with sore arms and sore chest in the bargain, I think.

Narrator: They struggled over a seemingly endless span of glaciers, their frozen clothing brushing stiff against their raw skin. The exhausted men marched for 26 hours straight. When Shackleton allowed them to rest, Worsley and Crean fell instantly asleep …

Ernest Shackleton: It will be disastrous if we all slumbered together. For sleep under such conditions merges into death. After 5 minutes, I shook them into consciousness, told them that they had slept for half-an-hour, and gave the word for a fresh start.

Narrator: The weary men continued to climb. Shackleton guessed they might be just 5 miles from Stromness whaling station. When he thought he heard the morning

Ernest Shackleton: We watched the chronometer for 7:00 o'clock when the whalers would be summoned to work. Right to the minute, the steam whistle came to us, borne clearly on the wind across miles of rock and snow. It was the first sound created by outside human agency that had come to our ears since we left in ... 1914. Pain and ache, boat journeys, marches, hunger, and fatigue seemed to belong to the limbo of forgotten things.

Narrator: Just before the Endurance departed, Shackleton visited here at the home of the station manager to celebrate his coming adventure. Now the manager answered the door and stared at the 3 haggard strangers -- clad in rags and grimed with soot -- and asked, "Who are you?"

Ernest Shackleton: Don't you know me? My name is Shackleton.

Narrator: 17 months had passed since Shackleton and his men vanished into the Antarctic. Within hours, a blizzard swept over South Georgia. Shackleton's legendary luck had been on their side. Now he hoped it would hold.

27 Roland Huntford: When Shackleton reached safety at Stromness, he still had 3 men waiting for him on the other side of the island. Next priority … well, the immediate priority was to save them. That was no problem. They got... a whaler fetched them. But then he was obsessed -- if that's the word -- preoccupied with saving the men left behind on Elephant Island. And he could not -- he would not -- rest until he had saved them.

Narrator: All of Stromness mobilized for the rescue mission. The station manager offered a ship and volunteers for the crew. Shackleton, Worsley, and Crean departed South Georgia, bound for Elephant Island.

But within days, they encountered pack ice. The Caird had navigated these waters just a month before. Now they were impassable to a steel steamship. Defeated by his old nemesis, Shackleton reluctantly turned back to port. The British Navy offered a ship, but Shackleton insisted on mounting his own rescue mission. He borrowed a fishing vessel and planned a new attempt. Worsley observed …

Frank Worsley: His anxiety for his men was so great that he couldn't rest. In those terrible months, I saw deep lines appear on his face. People thought that Shackleton was mad to enter the Winter ice with such a weak vessel.

Narrator: Locked in battle with the floes, the ship stopped short just 20 miles from Elephant Island. Again, Shackleton's hopes of a swift rescue were dashed. It could be months before the Winter pack ice retreated.

But for Wild and his men, time was running out. Young Perce Blackborow was gravely ill. His frostbitten toes had blackened and swelled. To save Blackborow's life, Dr. Alexander Macklin and surgeon James McIlroy were compelled to take action. They had no option but to operate in the crowded squalor of the hut.

John Blackborow: My grandfather was quite ill with gangrene on his toes. They needed to come off straightaway. They found some chloroform …-very little. They thought they didn't have any. They were going to operate without it at first, but they did find some in one of the packing cases. They raised the temperature of the inside the boat. And they proceeded to take my grandfather's toes off. The poor beggar never flinched.

Narrator: Blackborow's crewmates fared little better. All were severely malnourished, and one man had suffered a heart attack. Wild fought to rally their flagging hopes …

Frank Wild: Well, boys, patience for another week. The relief ship can't get through the pack.

Thomas Orde-Lees: He is always saying that "the ship" will be here next week. But of course, he says this just to keep up the spirits of those who are likely to become despondent.

Narrator: Thomas Orde-Lees expressed the fears the men fought to keep at bay. His was a lonely and ridiculed voice in a band of desperate optimists.

Roland Huntford: He played a part which is very essential in any group. He was a scapegoat. He was the man everybody loved to hate. And this is most essential because it's quite

28 important in keeping the cohesion of the group and also in keeping people's sanity. You must have somebody to hate.

Narrator: Orde-Lees warned rightly that game was becoming scarce and urged Wild to build up their reserves. But like Shackleton, Wild argued that it would destroy morale, signaling to the men that they would be stranded indefinitely.

Julian Ayer: If I was there on the ice, I'd back my grandfather any old time because you don't live on "morale", you know? You need food -- not morale -- to survive in the Antarctic for 18 months.

Narrator: Orde-Lees's nagging pessimism became more insistent as the weeks wore on. With his men on the brink of collapse, Wild felt compelled to act …

Frank WIld: I had to threaten to shoot him to make him keep his tongue between his teeth.

Narrator: But threats couldn't disguise the grim reality that the men confided to their diaries. The few stray penguins were not enough to stave off starvation. They were forced to dig up discarded scraps of putrid meat for food. Wild could no longer keep hope of rescue alive.

By August 30th, the castaways were reduced to boiling bones for sustenance. Frank Hurley and artist George Marston waded to the shore. They plunged bare arms into the icy surf for a few tiny shellfish to calm their gnawing hunger.

Suddenly, Hurley pointed out to sea …

Frank Hurley: I called Marston's attention to a curious piece of ice on the horizon which bore a striking resemblance to a ship. We immediately called out, "Ship ho!"

Narrator: Marston shouted to Wild …

Marston {voiceover}: Wild, there's a ship! Hadn't we better light a flare?

Narrator: The men scrambled to the beach. With Worsley at his side, Shackleton rowed toward the island:

Ernest Shackleton: We saw tiny black figures hurry to the beach and wave signals to us. As I came nearer, I called out, "Are you all well?" and Wild answered, "We are all well, Boss."

Narrator: Shackleton had fulfilled his ambition to save each and every man. They were headed for home at last. Worsley remarked of their reunion …

Frank Worsley: We got them aboard at 1:00 pm. And at 1:00 am, there was not a drop of liquor left! The poor fellows deserved a good time.

Narrator: Days later, the rescue ship steamed triumphantly to port in Chile to a hero's welcome. It had been 21 months since they sailed from civilization. Shackleton cabled his wife Emily:

Ernest Shackleton: "I have done it. Not a life lost, and we have been through Hell! Soon I will be home and then I will rest. Give my love and kisses to the children." 29 Narrator: In 1916, the survivors of the Endurance returned to a Europe transformed by World War I:

Ernest Shackleton: We were like men arisen from the dead to a World gone mad. Our minds accustomed themselves gradually to the tales of nations in arms, of deathless courage and unimagined slaughter, of a World conflict that had grown beyond all conception.

Roland Huntford: It was Shackleton's misfortune that this expedition took place during the Great War. Because when he got home, his achievement was overshadowed by greater events elsewhere.

Peter Wordie: The death of so many people in the trenches in the War made them feel that they had been, I could have said, nearly cowards--t hat they avoided 2 years of the War and they were lucky to be alive.

Narrator: Shackleton and many of the crew rushed to enlist. Within a month of his return to England, Tim McCarthy -- able seaman of the James Caird -- was killed in action.

Shackleton campaigned for royal recognition of his officers and crew. But their heroism seemed to pale in the public mind beside the tragic sacrifices of war.

Finally in 1918, the men of the Endurance were awarded the Polar Medal for exemplary service. Sailors Holness, Stephenson, and Vincent failed to receive the prize -- likely for disobeying orders. The honor was also withheld from Chippy McNeish.

Tom McNeish: In my opinion, they would never have got back home if it hadn't been for Chippy McNeish andwhat he done with the James Caird. He built the James Caird up. Chippy McNeish brought them home. I don't care what anybody says. Chippy McNeish brought them home!

Roland Huntford: When all was said and done, he [McNeish] was the man who saved them all by making the boat journey possible. Yet he was also the man who mutinied on the ice. For that, Shackleton never forgave him because in Shackleton's book, one act -- one single act of disloyalty -- outweighed anything else a man might do in a lifetime.

Narrator: For most of Shackleton's men, the bond of loyalty endured. When he threw off the humdrum of everyday life for a new expedition in 1921, 8 veterans of the Endurance answered the Boss's call. Among them were Frank Worsley, Frank Wild, and Alexander Macklin.

Shackleton was bound for the Antarctic once again. The Quest steered a southerly course with her crew of restless spirits. The stated aim was the circumnavigation of the Antarctic continent. But Shackleton and Wild reminisced and hatched grand schemes of someday hunting for pirate treasure.

As the ship neared her destination, Shackleton grew pensive, recalling the adventures of his younger days …

30 Ernest Shackleton: Anxiety has been probing deeply into me. Ah me, the years that have gone since -- in the pride of young manhood -- I first went forth to the fight. I grow old and tired, but must always lead on.