Rural Livelihood Transformations and Local Development in Cameroon, Ghana and Tanzania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

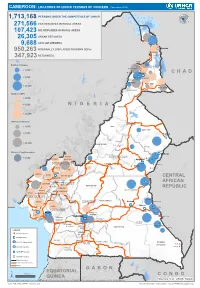

Page 1 C H a D N I G E R N I G E R I a G a B O N CENTRAL AFRICAN

CAMEROON: LOCATIONS OF UNHCR PERSONS OF CONCERN (November 2019) 1,713,168 PERSONS UNDER THE COMPETENCENIGER OF UNHCR 271,566 CAR REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 107,423 NIG REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 26,305 URBAN REFUGEES 9,688 ASYLUM SEEKERS 950,263 INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS (IDPs) Kousseri LOGONE 347,923 RETURNEES ET CHARI Waza Limani Magdeme Number of refugees EXTRÊME-NORD MAYO SAVA < 3,000 Mora Mokolo Maroua CHAD > 5,000 Minawao DIAMARÉ MAYO TSANAGA MAYO KANI > 20,000 MAYO DANAY MAYO LOUTI Number of IDPs < 2,000 > 5,000 NIGERIA BÉNOUÉ > 20,000 Number of returnees NORD < 2,000 FARO MAYO REY > 5,000 Touboro > 20,000 FARO ET DÉO Beke chantier Ndip Beka VINA Number of asylum seekers Djohong DONGA < 5,000 ADAMAOUA Borgop MENCHUM MANTUNG Meiganga Ngam NORD-OUEST MAYO BANYO DJEREM Alhamdou MBÉRÉ BOYO Gbatoua BUI Kounde MEZAM MANYU MOMO NGO KETUNJIA CENTRAL Bamenda NOUN BAMBOUTOS AFRICAN LEBIALEM OUEST Gado Badzere MIFI MBAM ET KIM MENOUA KOUNG KHI REPUBLIC LOM ET DJEREM KOUPÉ HAUTS PLATEAUX NDIAN MANENGOUBA HAUT NKAM SUD-OUEST NDÉ Timangolo MOUNGO MBAM ET HAUTE SANAGA MEME Bertoua Mbombe Pana INOUBOU CENTRE Batouri NKAM Sandji Mbile Buéa LITTORAL KADEY Douala LEKIÉ MEFOU ET Lolo FAKO AFAMBA YAOUNDE Mbombate Yola SANAGA WOURI NYONG ET MARITIME MFOUMOU MFOUNDI NYONG EST Ngarissingo ET KÉLLÉ MEFOU ET HAUT NYONG AKONO Mboy LEGEND Refugee location NYONG ET SO’O Refugee Camp OCÉAN MVILA UNHCR Representation DJA ET LOBO BOUMBA Bela SUD ET NGOKO Libongo UNHCR Sub-Office VALLÉE DU NTEM UNHCR Field Office UNHCR Field Unit Region boundary Departement boundary Roads GABON EQUATORIAL 100 Km CONGO ± GUINEA The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Sources: Esri, USGS, NOAA Source: IOM, OCHA, UNHCR – Novembre 2019 Pour plus d’information, veuillez contacter Jean Luc KRAMO ([email protected]). -

Phytochemical Screening and Antibacterial Activity of Medicinal Plants Used to Treat Typhoid Fever in Bamboutos Division, West Cameroon

Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science Vol. 5 (06), pp. 034-049, June, 2015 Available online at http://www.japsonline.com DOI: 10.7324/JAPS.2015.50606 ISSN 2231-3354 Phytochemical screening and antibacterial activity of medicinal plants used to treat typhoid fever in Bamboutos division, West Cameroon Tsobou Roger1, Mapongmetsem Pierre-Marie2, Voukeng Kenfack Igor3, Van Damme Patrick4 1Department of Plant Biology, University of Dschang, P.O.Box 67 Dschang, Cameroon; Department of Biological Sciences, University of Ngaoundéré, P.O.Box 454 Ngaoundéré, Cameroon. 2Department of Plant Production, Laboratory of Tropical and Subtropical Agriculture and Ethnobotany, 3Department of Biological Sciences, University of Ngaoundéré, P.O.Box 454 Ngaoundéré, Cameroon. 4Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Science, University of Dschang; Dschang, Cameroon. ABSTRACT ARTICLE INFO Article history: This study was undertaken to document how typhoid is traditionally treated in Bamboutos division. For this Received on: 02/03/2015 purpose thirty eight plants species were selected. These plants underwent phytochemical screening and Revised on: 13/04/2015 antibacterial study using standard procedures. The antibacterial tests using agar well diffusion method and Accepted on: 30/04/2015 microdilution assay indicated that, all the thirty eight plant samples showed activity against S. typhi, while S. Available online: 27/06/2015 paratyphi A and S. paratyphi B reacted on fifteen and fourteen plants respectively. The highest zones of inhibition were obtained from Senna alata with diameter of 24, 22.5 and 20.5 mm against S. paratyphi A, S. Key words: paratyphi B and S. typhi respectively at 160 mg/ml concentration. The lowest MIC values 128 µg/ml was Phytochemical screening, exhibited by the extract of Vitex doniana against Salmonella paratyphi A. -

Mountain Resources Expliotation For

International Journal of Geography and Régional Planning Research Vol.1,No.1,pp.1-12, March 2014 Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) MONTANE RESOURCES EXPLOITATION AND THE EMERGENCE OF GENDER ISSUES IN SANTA ECONOMY OF THE WESTERN BAMBOUTOS HIGHLANDS, CAMEROON Zephania Nji FOGWE Department of Geography, Box 3132, F.L.S.S., University of Douala ABSTRACT: Highlands have played key roles in the survival history of humankind. They are refuge heavens of valuable resources like fresh water endemic floral and faunal sanctuaries and other ecological imprints. The mountain resource base in most tropical Africa has been mined rather than managed for the benefit of the low-lying areas. The world over an appreciable population derives its sustenance directly from mountain resources and this makes for about one-tenth of the world’s poorest.The Western highlands of Cameroon are an archetypical territory of a high population density and an economically very active population. The highlands are characterised by an ecological fragility and a multi-faceted socio-economic dynamism at varied levels of poverty, malnutrition and under employment, yet about 80 percent of the Santa highlands’ population depends on its natural resource base of vast fertile land, fresh water and montane refuge forest for their livelihood. KEYWORDS: Montane Resources, Gender Issues, Santa Economy, Western Bamboutos, Cameroon INTRODUCTION The volcanic landscape on the western slopes of the Bamboutos mountain range slopes to the Santa Highlands is an area where agriculture in the form of crop production and animal rearing thrives with remarkable success. Arabica coffee cultivation was in extensive hectares cultivated at altitudes of about 1700m at the Santa Coffee Estate at Mile 12 in the 1970s and 1980s. -

Cameroon Watershed

Journal(of(Materials(and(( J. Mater. Environ. Sci., 2018, Volume 9, Issue 11, Page 3094-2104 Environmental(Sciences( ISSN(:(2028;2508( CODEN(:(JMESCN( http://www.jmaterenvironsci.com! Copyright(©(2018,( University(of(Mohammed(Premier(((((( (Oujda(Morocco( A typological study of the physicochemical quality of water in the Menoua- Cameroon watershed Santsa Nguefack Charles Vital1*, Ndjouenkeu Robert1, Ngassoum Martin Benoit2 , 1Laboratory of Food Physicochemistry, Department of Food Science and Nutrition National Advanced School of Agro- Industrial Sciences, University of Ngaoundéré, PO BOX 455,Ngaoundéré, Cameroon. 2Department of Industrial Chemistry and Environment, National Advanced School of Agro-Industrial Sciences, University of Ngaoundéré, PO BOX 455, Ngaoundéré, Cameroon. Received 29 Oct 2017 Abstract Revised 25 Dec 2018 Cameroon, a country in Central Africa with an outlet to the Atlantic Ocean in the Gulf Accepted 28 Dec 2018 of Guinea, holds enormous potentialities of water resources. These resources used for the supply of water for human consumption, etc., would be polluted by the Keywords intensification of anthropogenic activities, of which the most important recorded in the !!physicochemical, Menoua watershedof West Cameroon are agriculture and breeding. The objective of this !!pollution, work was to study the spatiotemporal parameters of the physicochemical quality !!Menoua watershed, parameters (temperature, pH, electrical conductivity, Turbidity, Nitrates, Ortho !!Anthropogenic Phosphates, Sulphates, Chloride, Potassium and Calcium) the Menoua activities, watershedthrough a main Principal Component Analysis (ACP). The results obtained showed that the pH, turbidity and orthophosphate have levels which are in contradiction !!Water for human consumption. with WHO standards. The physicochemical parameters of this water showed significant spatial and seasonal variations, the causes of which probably related to the human activities generating pollutants. -

Status of Lgbti People in Cameroon, Gambia, Ghana and Uganda

STATUS OF LGBTI PEOPLE IN CAMEROON, GAMBIA, GHANA AND UGANDA 3.12.2015 Finnish Immigration Service Country Information Service Public Theme Report 1 (123) Table of contents Disclaimer .................................................................................................................................................... 3 List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 7 1.1. The colonial legacy of anti-sodomy laws ......................................................................................... 7 1.2. The significance of current laws criminalising same-sex conduct ............................................. 11 1.3. Particularities of the situation of lesbians and bisexual women................................................. 12 1.4. Particularities of the situation of transgender and intersex people ........................................... 14 1.5. Violations of international and regional human rights law .......................................................... 14 2. Cameroon .............................................................................................................................................. 18 2.1. The legal framework ........................................................................................................................ -

History, External Influence and Political Volatility in the Central African Republic (CAR)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Journal for the Advancement of Developing Economies Economics Department 2014 History, External Influence and oliticalP Volatility in the Central African Republic (CAR) Henry Kam Kah University of Buea, Cameroon Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jade Part of the Econometrics Commons, Growth and Development Commons, International Economics Commons, Political Economy Commons, Public Economics Commons, and the Regional Economics Commons Kam Kah, Henry, "History, External Influence and oliticalP Volatility in the Central African Republic (CAR)" (2014). Journal for the Advancement of Developing Economies. 5. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jade/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Economics Department at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal for the Advancement of Developing Economies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Journal for the Advancement of Developing Economies 2014 Volume 3 Issue 1 ISSN:2161-8216 History, External Influence and Political Volatility in the Central African Republic (CAR) Henry Kam Kah University of Buea, Cameroon ABSTRACT This paper examines the complex involvement of neighbors and other states in the leadership or political crisis in the CAR through a content analysis. It further discusses the repercussions of this on the unity and leadership of the country. The CAR has, for a long time, been embroiled in a crisis that has impeded the unity of the country. It is a failed state in Africa to say the least, and the involvement of neighboring and other states in the crisis in one way or the other has compounded the multifarious problems of this country. -

Evaluating the Constraints and Opportunities of Maize Production in the West Region of Cameroon for Sustainable Development

Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa (Volume 13, No.4, 2011) ISSN: 1520-5509 Clarion University of Pennsylvania, Clarion, Pennsylvania EVALUATING THE CONSTRAINTS AND OPPORTUNITIES OF MAIZE PRODUCTION IN THE WEST REGION OF CAMEROON FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT Godwin Anjeinu Abu1, Raoul Fani Djomo-Choumbou1 and Stephen Adogwu Okpachu2 1. Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Agriculture PMB 2373, Makurdi Benue State- Nigeria 2. Federal College of Education (Technical), Potiskum, Yobe State, Nigeria ABSTRACT A study of Evaluating the constraints and opportunities of Maize production in the West Region of Cameroon was carried out using primary and secondary data collected. One hundred and twenty (120) maize farmers randomly selected from eight (8) villages were interviewed using structured questionnaire. Data from the study were analyzed using descriptive statistics such as frequency distribution, percentages, and inferential statistics such as multiple linear regressions. The study found that most maize farmers in the study area were small scale farmers and are full time farmers, the major maize production constraints was poor access to credit facilities. it was also found any unit increase in the quantity of any of the resources used for maize production will increase maize output by the value of their estimated coefficients respectively , however to raise maize production, the study recommend that financial institutions such as agricultural and community banks should be established in the study area with the simple procedure of securing loans. The relevant government agencies and non- governmental organization should mobilize the maize farmers to form themselves into formidable group so that they can derive maximum benefit of collective union. -

How Flat Funding Is Undermining U.S. Global AIDS Programs Flat Funding Is an Insidious Threat to Ending the AIDS Pandemic

DEADLY IMPACT How Flat Funding Is Undermining U.S. Global AIDS Programs Flat funding is an insidious threat to ending the AIDS pandemic. The impact is long-lasting, far-reaching, and deadly. THE COST OF FLAT FUNDING With only twelve years left to achieve the global goal of ending AIDS as a pandemic, international funding for HIV has reached its lowest level since 2010, declining for the second year in a row—by 7% in 2016.1 International funding for HIV has been stuck in neutral and creeping into reverse, with funds from the U.S. stagnant just as low- and middle-income countries are increasing their com- mitments. Flat funding by the U.S. to its global AIDS program over the past five years is having a deadly impact—undermining treatment and prevention scale up in countries where responses to the epidemic are already dangerously off track. The legacy of flat funding is so pervasive that programs are deciding which high-prevalence regions are so far behind that they will have to wait until others reach saturation. After years of flat funding, a rapid scale up in resources is the only way to achieve a course correction. There are three countries particularly in need of a rapid course correction: South Africa, Mozambique, and Cameroon. These three countries alone represent one-third of new infections and over one-quarter of AIDS-related deaths in sub-Saharan Africa. In a different context, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria (the Global Fund) might together fund a more rapid infusion of HIV services to address the crisis, but today flat funding is making it impossible to deploy sufficient resources and programming. -

Cameroon : Adamawa, East and North Rgeions

CAMEROON : ADAMAWA, EAST AND NORTH RGEIONS 11° E 12° E 13° E 14° E N 1125° E 16° E Hossere Gaval Mayo Kewe Palpal Dew atan Hossere Mayo Kelvoun Hossere HDossere OuIro M aArday MARE Go mbe Trabahohoy Mayo Bokwa Melendem Vinjegel Kelvoun Pandoual Ourlang Mayo Palia Dam assay Birdif Hossere Hosere Hossere Madama CHARI-BAGUIRMI Mbirdif Zaga Taldam Mubi Hosere Ndoudjem Hossere Mordoy Madama Matalao Hosere Gordom BORNO Matalao Goboum Mou Mayo Mou Baday Korehel Hossere Tongom Ndujem Hossere Seleguere Paha Goboum Hossere Mokoy Diam Ibbi Moukoy Melem lem Doubouvoum Mayo Alouki Mayo Palia Loum as Marma MAYO KANI Mayo Nelma Mayo Zevene Njefi Nelma Dja-Lingo Birdi Harma Mayo Djifi Hosere Galao Hossere Birdi Beli Bili Mandama Galao Bokong Babarkin Deba Madama DabaGalaou Hossere Goudak Hosere Geling Dirtehe Biri Massabey Geling Hosere Hossere Banam Mokorvong Gueleng Goudak Far-North Makirve Dirtcha Hwoli Ts adaksok Gueling Boko Bourwoy Tawan Tawan N 1 Talak Matafal Kouodja Mouga Goudjougoudjou MasabayMassabay Boko Irguilang Bedeve Gimoulounga Bili Douroum Irngileng Mayo Kapta Hakirvia Mougoulounga Hosere Talak Komboum Sobre Bourhoy Mayo Malwey Matafat Hossere Hwoli Hossere Woli Barkao Gande Watchama Guimoulounga Vinde Yola Bourwoy Mokorvong Kapta Hosere Mouga Mouena Mayo Oulo Hossere Bangay Dirbass Dirbas Kousm adouma Malwei Boulou Gandarma Boutouza Mouna Goungourga Mayo Douroum Ouro Saday Djouvoure MAYO DANAY Dum o Bougouma Bangai Houloum Mayo Gottokoun Galbanki Houmbal Moda Goude Tarnbaga Madara Mayo Bozki Bokzi Bangei Holoum Pri TiraHosere Tira -

Assessment of Prunus Africana Bark Exploitation Methods and Sustainable Exploitation in the South West, North-West and Adamaoua Regions of Cameroon

GCP/RAF/408/EC « MOBILISATION ET RENFORCEMENT DES CAPACITES DES PETITES ET MOYENNES ENTREPRISES IMPLIQUEES DANS LES FILIERES DES PRODUITS FORESTIERS NON LIGNEUX EN AFRIQUE CENTRALE » Assessment of Prunus africana bark exploitation methods and sustainable exploitation in the South west, North-West and Adamaoua regions of Cameroon CIFOR Philip Fonju Nkeng, Verina Ingram, Abdon Awono February 2010 Avec l‟appui financier de la Commission Européenne Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... i ABBREVIATIONS ...................................................................................................... ii Abstract .................................................................................................................. iii 1: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Problem statement ...................................................................................... 2 1.3 Research questions .......................................................................................... 2 1.4 Objectives ....................................................................................................... 3 1.5 Importance of the study ................................................................................... 3 2: Literature Review ................................................................................................. -

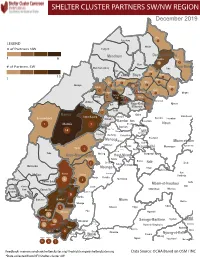

NW SW Presence Map Complete Copy

SHELTER CLUSTER PARTNERS SW/NWMap creation da tREGIONe: 06/12/2018 December 2019 Ako Furu-Awa 1 LEGEND Misaje # of Partners NW Fungom Menchum Donga-Mantung 1 6 Nkambe Nwa 3 1 Bum # of Partners SW Menchum-Valley Ndu Mayo-Banyo Wum Noni 1 Fundong Nkum 15 Boyo 1 1 Njinikom Kumbo Oku 1 Bafut 1 Belo Akwaya 1 3 1 Njikwa Bui Mbven 1 2 Mezam 2 Jakiri Mbengwi Babessi 1 Magba Bamenda Tubah 2 2 Bamenda Ndop Momo 6b 3 4 2 3 Bangourain Widikum Ngie Bamenda Bali 1 Ngo-Ketunjia Njimom Balikumbat Batibo Santa 2 Manyu Galim Upper Bayang Babadjou Malentouen Eyumodjock Wabane Koutaba Foumban Bambo7 tos Kouoptamo 1 Mamfe 7 Lebialem M ouda Noun Batcham Bafoussam Alou Fongo-Tongo 2e 14 Nkong-Ni BafouMssamif 1eir Fontem Dschang Penka-Michel Bamendjou Poumougne Foumbot MenouaFokoué Mbam-et-Kim Baham Djebem Santchou Bandja Batié Massangam Ngambé-Tikar Nguti Koung-Khi 1 Banka Bangou Kekem Toko Kupe-Manenguba Melong Haut-Nkam Bangangté Bafang Bana Bangem Banwa Bazou Baré-Bakem Ndé 1 Bakou Deuk Mundemba Nord-Makombé Moungo Tonga Makénéné Konye Nkongsamba 1er Kon Ndian Tombel Yambetta Manjo Nlonako Isangele 5 1 Nkondjock Dikome Balue Bafia Kumba Mbam-et-Inoubou Kombo Loum Kiiki Kombo Itindi Ekondo Titi Ndikiniméki Nitoukou Abedimo Meme Njombé-Penja 9 Mombo Idabato Bamusso Kumba 1 Nkam Bokito Kumba Mbanga 1 Yabassi Yingui Ndom Mbonge Muyuka Fiko Ngambé 6 Nyanon Lekié West-Coast Sanaga-Maritime Monatélé 5 Fako Dibombari Douala 55 Buea 5e Massock-Songloulou Evodoula Tiko Nguibassal Limbe1 Douala 4e Edéa 2e Okola Limbe 2 6 Douala Dibamba Limbe 3 Douala 6e Wou3rei Pouma Nyong-et-Kellé Douala 6e Dibang Limbe 1 Limbe 2 Limbe 3 Dizangué Ngwei Ngog-Mapubi Matomb Lobo 13 54 1 Feedback: [email protected]/ [email protected] Data Source: OCHA Based on OSM / INC *Data collected from NFI/Shelter cluster 4W. -

Shelter Cluster Cameroon – Meeting Minutes Meeting: Shelter Cluster

Shelter Cluster Cameroon ShelterCluster.org Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter Yaounde 30 October 2020 Shelter Cluster Cameroon – Meeting Minutes Meeting: Shelter Cluster Date: 29.10.2020 Time: 15:00 Meeting Facilitator: Medar Mitima Kajemba Location: Yaounde Minutes Prepared By: Medar Mitima Kajemba Location: UNHCR Office Agenda • Introduction and round table • Agreement on frequency of Yaounde shelter cluster meeting. • Shelter-NFI activities-presentation-Who is doing What and Where. • Current Shelter-NFI needs(gaps) in the NW/SW regions. • Recommendation • AOB Introduction and round table Everyone introduced themselves by name, organization and position in the organization, which allowed participants to get to know each other Agreement on frequency of Yaounde shelter cluster meeting. The schedule of meetings will be set after consultation with the field clusters to ensure that inputs from the field will be available before each meeting in Yaounde Shelter-NFI activities-presentation-Who is doing What and Where Catholic Relief Services (CRS): CRS's shelter and resettlement program is part of its RRF (Rapid Response Fund) program, which has just been launched in 4 African countries including Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger and Cameroon. The West Africa RRF mechanism is designed to meet unanticipated needs as they emerge, ensuring rapid, short-term, life-saving assistance through Water Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH), Multi-Purpose Cash (MPCA), and Shelter and Settlement (S&S) interventions. Through organizational and emergency response capacity building, the project will emphasize the use of local partner networks to deepen the potential for sustainability and transition. In Cameroon, the project will cover Far North, East, North West and South West regions.