August 15, 2005 Report to the President and Congress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Government of Guam

2 te GENERAYourL ELEC TIVoiceON 2012 YourGENERA L Vote ELECTION 2012 Vo r r ou Y , , ce Your guide to Election 2012 oi V INSIDE ur Voter initiative: he Pacific Daily tion on the for- community to help Yo Proposal A News provides this profit bingo pro- support public edu- guide to the 2012 posal that will be cation, safety and on the General health agencies. 12 Page 3 General Election to Election ballot On the other side help you, our readers 20 Nov. 6. of the argument, crit- and voters, make the 1, Congressional delegate Proponents of ics say passing the most informed deci- er Proposition A, pri- initiative could bring Pages 4, 5 Tsion about which marily the Guam- harm to Guam’s mb candidates have what it takes to bring Japan Friendship non-profit organiza- ve the island into the future. Village, only re- tions, a number of No Senatorial candidates We contacted candidates before the Gen- cently became vo- which rely on bingo , , — Democrat eral Election to get information about their cal — attending as a method of rais- ay work experience and education. We also village meetings and taking out radio spots ing funds to support their cause. One of the sd Pages 7~13 sent election-related questions to delegate and television ads calling for the communi- more vocal groups, “Keep Guam Good” ur and legislative candidates and asked them to ty’s support. raise concerns that for-profit bingo would be Th , , submit written responses. One legislative Proponents say the facility that the passage too similar to gambling and with the passage Senatorial candidates of the initiative would allow if passed by of the initiative would bring social ills that m m candidate, former Sen. -

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 07/29/2016 2:00:10 PM

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 07/29/2016 2:00:10 PM OMB No. 1124-0002; Expires April 30,2017 U.S. Depa rtment of Justice Supplemental Statement Washington, DC 20530 Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended For Six Month Period Ending 6/30/2016 (Insert date) I - REGISTRANT 1. (a) Name of Registrant (b) Registration No. Podesta Group, Inc. 5926 (c) Business Address(es) of Registrant 1001 G Street NW Suite 1000 West Washington, DC 20001 2. Has there been a change in the information previously furnished in connection With the following? (a) If an individual: (1) Residence address(es) Yes • No • (2) Citizenship Yes • No • (3) Occupation Yes • No • (b) If an organization: (1) Name Yes • No H (2) Ownership or control Yes • No 13 (3) Branch offices Yes • No 0 (c) Explain fully all changes, if any, indicated in Items (a) and (b) above, (not applicable) IF THE REGISTRANT IS AN INDIVIDUAL, OMIT RESPONSE TO ITEMS 3,4, AND 5(a). 3. If you have previously filed Exhibit C, state whether any changes therein have occurred during this 6 month reporting period. Yes • No H If yes, have you filed an amendment to the Exhibit C? Yes • No • Ifno, please attach the required amendment. 1 The Exhibit C, for which no printed form is provided, consists ofa true copy of the charter, articles of incorporation, association, and by laws ola registrant that is an organization. (A waiver of the requirement to file an Exhibit C may be obtained for good cause upon written application to the Assistant Attorney General, National Security Division, U.S. -

A Growing Diversity

A Growing Diversity 1993–2017 In late April 1975, eight-year-old Anh (Joseph) Cao’s long and improbable odyssey to the halls of Congress began as North Vietnamese communists seized the southern capital city of Saigon.1 The trajectory of the soft-spoken, bookish Cao toward Capitol Hill stands out as one of the most remarkable in the modern era, even as it neatly encapsulated post-1965 Asian immigration patterns to the United States. Still, the origins of Cao’s story were commonplace. For three decades, conflict and civil war enveloped his country. After the Vietnamese threw off the yoke of French colonialism following World War II, a doomed peace accord in 1954 removed the French military and partitioned Vietnam. The new government in South Vietnam aligned with Western world powers, while North Vietnam allied with communist states. Amid the Cold War, the U.S. backed successive Saigon regimes against communist insurgents before directly intervening in 1965. A massive ground and air war dragged on inconclusively for nearly a decade. More than 58,000 American troops were killed, and more than three million South and North Vietnamese perished.2 Public opposition in the United States eventually forced an end to the intervention. America’s decision to withdraw from Vietnam shattered Joseph Cao’s family just as it did many thousands of others as communist forces soon swamped the ineffectual government and military in the South. In 2011 Japanese-American veterans received the Congressional Gold Medal for their valor during World War II. The medal included the motto of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, “Go for Broke.” Nisei Soldiers of World War II Congressional Gold Medal Obverse © 2011 United States Mint 42940_08-APA-CE3.indd 436 2/13/2018 12:04:16 PM 42940_08-APA-CE3.indd 437 2/13/2018 12:04:17 PM Just days before Saigon fell, Cao’s mother, Khang Thi Tran, spirited one of her daughters and two sons, including Anh, to a U.S. -

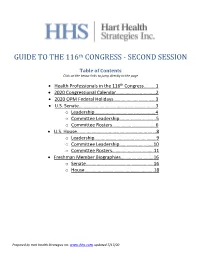

GUIDE to the 116Th CONGRESS

th GUIDE TO THE 116 CONGRESS - SECOND SESSION Table of Contents Click on the below links to jump directly to the page • Health Professionals in the 116th Congress……….1 • 2020 Congressional Calendar.……………………..……2 • 2020 OPM Federal Holidays………………………..……3 • U.S. Senate.……….…….…….…………………………..…...3 o Leadership…...……..…………………….………..4 o Committee Leadership….…..……….………..5 o Committee Rosters……….………………..……6 • U.S. House..……….…….…….…………………………...…...8 o Leadership…...……………………….……………..9 o Committee Leadership……………..….…….10 o Committee Rosters…………..…..……..…….11 • Freshman Member Biographies……….…………..…16 o Senate………………………………..…………..….16 o House……………………………..………..………..18 Prepared by Hart Health Strategies Inc. www.hhs.com, updated 7/17/20 Health Professionals Serving in the 116th Congress The number of healthcare professionals serving in Congress increased for the 116th Congress. Below is a list of Members of Congress and their area of health care. Member of Congress Profession UNITED STATES SENATE Sen. John Barrasso, MD (R-WY) Orthopaedic Surgeon Sen. John Boozman, OD (R-AR) Optometrist Sen. Bill Cassidy, MD (R-LA) Gastroenterologist/Heptalogist Sen. Rand Paul, MD (R-KY) Ophthalmologist HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Rep. Ralph Abraham, MD (R-LA-05)† Family Physician/Veterinarian Rep. Brian Babin, DDS (R-TX-36) Dentist Rep. Karen Bass, PA, MSW (D-CA-37) Nurse/Physician Assistant Rep. Ami Bera, MD (D-CA-07) Internal Medicine Physician Rep. Larry Bucshon, MD (R-IN-08) Cardiothoracic Surgeon Rep. Michael Burgess, MD (R-TX-26) Obstetrician Rep. Buddy Carter, BSPharm (R-GA-01) Pharmacist Rep. Scott DesJarlais, MD (R-TN-04) General Medicine Rep. Neal Dunn, MD (R-FL-02) Urologist Rep. Drew Ferguson, IV, DMD, PC (R-GA-03) Dentist Rep. Paul Gosar, DDS (R-AZ-04) Dentist Rep. -

Joakim Peter Guam

196 the contemporary pacific • spring 2000 gress also reelected Congressman Jack ruled in favor of the national govern- Fritz as its Speaker, Congressman ment, and the states were already Claude Phillip as vice speaker, and making plans to appeal the case. In Senator Joeseph Urusemal of Yap as the meantime, the issue did not get the new floor leader. A special elec- the necessary support from voters in tion was held in July 1999 to fill the the July elections. Given these results, vacant senate seats from Pohnpei and the fate of the court appeal is unclear. Chuuk. In the special election, Resio Furthermore, in relation to the second Moses, Pohnpei, and Manny Mori, proposed amendment defeated by Chuuk, were elected to Congress. voters, the Congress passed a law, By act of petition, three amend- effective 1 October 1998, which ments to the FSM Constitution were increases the states’ share of revenue put on the ballot during the general to 70 percent! elections. The amendments center joakim peter around the issues of revenue sharing and ownership of resources. One of the challenges to national unity in Guam the FSM will always be the issue of resources, especially since one of the Although Guam came through unique features of the federation is 1998–99 without a punishing the weaker national government that typhoon, President Clinton hit Guam allows the state governments more like a storm, as did the November flexibility and power. The first pro- general elections, Chinese illegal posal is to amend section 2 of Article entrants, and the effort to restructure I (Territory of Micronesia) to basi- Guam’s school system. -

SENATE—Wednesday, November 30, 2011

November 30, 2011 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE, Vol. 157, Pt. 13 18343 SENATE—Wednesday, November 30, 2011 The Senate met at 10 a.m. and was SCHEDULE family will have $1,000 less to spend on called to order by the Honorable Mr. REID. Madam President, fol- food, clothing, and diapers next year— KIRSTEN E. GILLIBRAND, a Senator from lowing leader remarks, the Senate will except those 350,000 people. the State of New York. be in morning business until 10:30 a.m. Republicans can continue to try to Following morning business, the Sen- protect people who earn an average of PRAYER ate will resume consideration of S. $3 million apiece. We are not going to do that, not in today’s economy. In The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- 1867. The filing deadline for second-de- other words, Republicans are increas- fered the following prayer: gree amendments to the Defense bill is ing taxes on nearly every American Let us pray. 10:30 a.m. today. At about 11 o’clock, family to protect people who make an Holy, holy, holy, Lord God of Hosts, there will be a cloture vote on S. 1867. average of $37,500 a week—far more Heaven and Earth are filled with Your It is my understanding the vote will than most Americans make in a year. glory. Lord, You have given us the be at 11 o’clock. Is that right, Madam You can take Nevada, you can take hope that Your kingdom shall come on President? It is not about 11, it will be Kentucky—take Kentucky, the home Earth. -

Senator Michael F.Q. San Nicolas

Senator Michael F.Q. San Nicolas (Jtairman - Committ!?t" on Financt: & Taxation, General Government O]><".rations, and 'fouth Development J A1itu(lrentai -Tres J1.la Lihesiahiran t,--;udhan I 33ru Guam Legislature February 15, 2016 TI1e Honorable Judith T. Won Pat, 1:d.D. Speaker I Mina 'Trentai Tres no Lihesla1urar1 Guilhan l 55 Hesler Place Hagatna, Guam 96910 VIA: '!be Honorable Rory J, Respicio All/!/ Chairman / v - - Committee on Rules, Federal, Foreign & Micronesian Affairs, Human & Naturnl Resources, Election Reform, and Capitol District RE: Sponsor's Report on Resolution No. 257-33 (COR) Dear Speaker Won Pat, Hilfa adai! Trnnsmitted herewith is the Sponsor's Report on Resolution No, 257-33 (COR) ·-"Relative to expressing l Liheslaturan Gulihan's unreserved support for the introduction ofH,R, 3642 into the United States House of Representatives hy the Honorable Congresswoman Madeleine 7,, Bordallo." Committee votes are as follows: TO DO PASS TO NOT PASS TO REPORT OUT ONLY TO ABSTAIN TO PLACE IN NACTIVE FILE LAS DNA Building, 238 Archbishop Flores St. Suite 407 Hagati\a, Guam 96910 (671) 472 - 6453 I [email protected] I www.senatmsarrnicolas.com Senator Michael F.Q. San Nicolas Ch.airman - Committee on Finance & T a:xation, General Goverrunent Open1tions, and Youth Developtnent l !Y1in1.:ftrcntai Tres N1z L-ihi'$/aturari (~tulhan I 33ro Gua1n Legislature SPONSOR'S REPORT Resolution No. 257-33 (COR) "Relative to expressing I Liheslaturan Guahan 's unreserved support for the introduction of H.R. 3642 into the United States House of Representatives by the Honorable Congresswoman Madeleine Z. Bordallo." DNA Building, 238 Archbishop Flores St Suite 407 Hagati\a, Guam 96910 (671) 472 - 64531 [email protected] I www.senatorsannicolas.mm Senator Michael F.Q. -

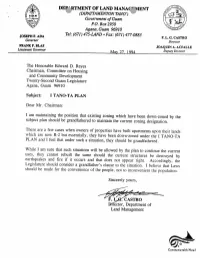

P.O. Box 2950

DEPtRTMENT OF LAND MANAYMENT (DIPATTAMENTON TANO') Government of Guam P.O.Box 2950 Agana, Guam 96910 Tel: (671)475-LAND Fax: (671)477-0883 JOSEPH F. ADA F. L. G. CASTRO Governor Director FRANK F. BLAS JOAQUIN A. ACFALLE Deputy Director The Honorable Edward D. Reyes Chairman, Committee on Housing and Community Development Twenty-Second Guam Legislature Agana, Guam 96910 Subject: I TANO-TA PLAN Dear Mr. Chairman: I am maintaining the position that existing zoning which have been down-zoned by the subject plan should be grandfathered to maintain the current zoning designation. There are a few cases when owners of properties have built apartments upon their lands which are now R-2 but essentially, they have been down-zoned under the I TANO-TA PLAN and I feel that under such a situation, they should be grandfathered. While I am sure that such situations will be allowed by the plan to continue the current uses, they cannot rebuilt the same should the current structures be destroyed by earthquakes and fire if it occurs and that does not appear right. Accordingly, the Legislature should consider a grandfather's clause to the situation. I believe that Laws should be made for the convenience of the people, not to inconvenient the population. Sincerely yours, E&ctor, Department of Land Management Commonwealth Now! n 0 GUAM CHAMBER OF COMMERCE PARTNERS IN PROGRESS 173 Aspinall Avenue, Ada Plan Center, Suite 102 P.O.Box 283 Agana, GU 96910 TEL:472-631 118001 FAX: 472-6202 June 1, 1994 Senator Edward D. Reyes Chairman Committee on Housing & Community Development 22nd Guam Legislature 228 Archbishop Flores Street Agana, Guam 96910 Dear Mr. -

Advances in Research Using the C-SPAN Archives

The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research Volume 3 Article 1 11-15-2016 Advances in Research Using the C-SPAN Archives Robert X. Browning Purdue University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/ccse Part of the American Politics Commons Recommended Citation Browning, Robert X. (2016) "Advances in Research Using the C-SPAN Archives," The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research: Vol. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/ccse/vol3/iss1/1 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Advances in Research Using the C-SPAN Archives Cover Page Footnote To purchase a hard copy of this publication, visit: http://www.thepress.purdue.edu/titles/format/ 9781557537621 This article is available in The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/ccse/vol3/iss1/1 Browning: Advances in Research Using the C-SPAN Archives ADVANCES IN RESEARCH USING THE C-SPAN ARCHIVES Published by Purdue e-Pubs, 2016 1 The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research, Vol. 3 [2016], Art. 1 OTHER BOOKS IN THE C-SPAN ARCHIVES SERIES The C-SPAN Archives: An Interdisciplinary Resource for Discovery, Learning, and Engagement Exploring the C-SPAN Archives: Advancing the Research Agenda https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/ccse/vol3/iss1/1 2 Browning: Advances in Research Using the C-SPAN Archives ADVANCES IN RESEARCH USING THE C-SPAN ARCHIVES edited by Robert X. Browning Purdue University Press, West Lafayette, Indiana Published by Purdue e-Pubs, 2016 3 The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research, Vol. -

UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Chamorros, ghosts, non-voting delegates : GUAM! where the production of America's sovereignty begins Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9x72002w Author Bevacqua, Michael Lujan Publication Date 2010 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Chamorros, Ghosts, Non-voting Delegates: GUAM ! Where the Production of America’s Sovereignty Begins A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies by Michael Lujan Bevacqua Committee in charge: Professor Yen Le Espiritu, Chair Professor John D. Blanco Professor Keith L. Camacho Professor Ross H. Frank Professor K. Wayne Yang 2010 © Michael Lujan Bevacqua, 2010 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Michael Lujan Bevacqua is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ______________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2010 iii DEDICATION Este para Si Sumåhi yan Si Akli’e’ Este lokkue’ para i anitin i hagas matai na Maga’låhi Si Chelef (taotao Orote). Ha gof tungo’ taimanu pumuha i sakman -

Gutierrez, Bordallo Win Guam Elections

I arianas ~riet~~ Micronesia's Leading Newspaper Since 1972 b&1 ews New tax bill rea By Rafael H. Arroyo bill which is expected to raise line with an earlier commitment ing a series of public hearings on between 521 to $25 million in Mafnasmadeduring the tax hear the proposals. THE HOUSE Ways & Means additional revenues in the first ings that witnesses will be in The good pointsofthetwoother Subcommittee on Tax Reform is year of its implementation. formed one last time prior to fi proposals, House Bill 8-250 and set to endorse to the full House a "The report will be ready for nalization of the tax bill. House Bill 9-83, are to be taken !' tax reform measure based on the submission to the leadership on The subcommittee is generally intoaccount,accordingtoMafnas, II tax proposal submitted by the or before Monday," Mafnas said. backing the Chamber's alterna when the final versionof the sub I Saipan Chamber of Commerce. "But we intend to meet with rep tive tax proposal over the stitute bill is drafted. According to House Vice resentatives of the Chamber and governor's and the speaker's tax UndertheChamber's proposal, SpeakerandSubcommiueeChair the Administration to discuss the proposals, after having received a surtax of 10% over and above man Jesus P. Mafnas, thepanel is finalversionofthebill,"he added. input from a wide range of wit ali CNMI taxes is to be charged poised to submit the substitute The "wrap up" meeting is in nesseswithinthecommunitydur- taxpayers, except for those with rebate base of $2,000 or less. -

GUAM! Where the Production of America’S Sovereignty Begins! Sinthomes, Slogans and Sovereignty ……………………… ………… 1 Decolonizing Space …………………………………

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Chamorros, Ghosts, Non-voting Delegates: GUAM ! Where the Production of America’s Sovereignty Begins A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies by Michael Lujan Bevacqua Committee in charge: Professor Yen Le Espiritu, Chair Professor John D. Blanco Professor Keith L. Camacho Professor Ross H. Frank Professor K. Wayne Yang 2010 © Michael Lujan Bevacqua, 2010 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Michael Lujan Bevacqua is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ______________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2010 iii DEDICATION Este para Si Sumåhi yan Si Akli’e’ Este lokkue’ para i anitin i hagas matai na Maga’låhi Si Chelef (taotao Orote). Ha gof tungo’ taimanu pumuha i sakman i enimigu-ña. Puede’ ha (gi este na tinige’-hu) para bai hu osge gui’. iv EPIGRAPH No one is as powerful as we make them out to be. Alice Walker v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ………………………………………………………………... iii Dedication ……………………………………………………………............. iv Epigraph ……………………………………………………………………… v Table of Contents ……………………………………………………….…… vi Acknowledgements ………………………..…………………....……………