East–West Interchanges in American

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graphic Recording by Terry Laban of the Global Health Matters Forum on March 25, 2020 Co-Hosted by Craftnow and the Foundation F

Graphic Recording by Terry LaBan of the Global Health Matters Forum on March 25, 2020 Co-Hosted by CraftNOW and the Foundation for Advancement of International Medical Education and Research With Gratitude to Our 2020 Contributors* $10,000 + Up to $500 Jane Davis Barbara Adams Drexel University Lenfest Center for Cultural Anonymous Partnerships Jeffrey Berger Patricia and Gordon Fowler Sally Bleznack Philadelphia Cultural Fund Barbara Boroff Poor Richard’s Charitable Trust William Burdick Lisa Roberts and David Seltzer Erik Calvo Fielding Rose Cheney and Howie Wiener $5,000 - $9,999 Rachel Davey Richard Goldberg Clara and Ben Hollander Barbara Harberger Nancy Hays $2,500 - $4,999 Thora Jacobson Brucie and Ed Baumstein Sarah Kaizar Joseph Robert Foundation Beth and Bill Landman Techné of the Philadelphia Museum of Art Tina and Albert Lecoff Ami Lonner $1,000 - $2,499 Brenton McCloskey Josephine Burri Frances Metzman The Center for Art in Wood Jennifer-Navva Milliken and Ron Gardi City of Philadelphia Office of Arts, Culture, and Angela Nadeau the Creative Economy, Greater Philadelphia Karen Peckham Cultural Alliance and Philadelphia Cultural Fund Pentimenti Gallery The Clay Studio Jane Pepper Christina and Craig Copeland Caroline Wishmann and David Rasner James Renwick Alliance Natalia Reyes Jacqueline Lewis Carol Saline and Paul Rathblatt Suzanne Perrault and David Rago Judith Schaechter Rago Auction Ruth and Rick Snyderman Nicholas Selch Carol Klein and Larry Spitz James Terrani Paul Stark Elissa Topol and Lee Osterman Jeffrey Sugerman -

Floating World: the Influence of Japanese Printmaking

Floating World: The Influence of Japanese Printmaking Ando Hiroshige, Uraga in Sagami Province, from the series Harbors of Japan, 1840-42, color woodcut, collection of Ginna Parsons Lagergren Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Poem by Sarumaru Tayû: Soga Hakoômaru, from the series Ogura Imitations of One Hundred Poems by One Hundred Poets, 1845-48, color woodcut, collection of Jerry & Judith Levy Floating World: The Influence of Japanese Printmaking June 14–August 24, 2013 Floating World explores the influence of Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock printmaking on American and European artists from the late 19th century to the present. A selection of Japanese prints sets the stage for Arts & Crafts era works by Charles Bartlett, Elizabeth Colborne, Arthur Wesley Dow, Frances Gearhart, Edna Boies Hopkins, Bertha Lum and Margaret Jordan Patterson. Woodcuts by Helen Franken- thaler illuminate connections between Abstract Expressionism and Japanese art. Prints by Annie Bissett, Kristina Hagman, Ellen Heck, Tracy Lang, Eva Pietzcker and Roger Shimomura illustrate the ongo- ing allure of ukiyo-e as the basis for innovations in printmaking today. In 1891, AmerIcAn ArtisT woodblock prints that depicted the ARThuR WESLEY DOW wrote that “floating world” of leisure and en- “one evening with Hokusai gave me tertainment. Artists began depicting more light on composition and deco- teahouses, festivals, theater and activi- rative effect than years of study of ties like the tea ceremony, flower ar- pictures. I surely ought to compose in an ranging, painting, calligraphy and music. entirely different manner.”1 Dow wrote Landscapes, birds, flowers and scenes of the letter after discovering a book of daily life were also popular. -

Collection Highlights Since Its Founding in 1924, the Kalamazoo Institute of Arts Has Built a Collection of Nearly 5,000 Artworks

Collection Highlights Since its founding in 1924, the Kalamazoo Institute of Arts has built a collection of nearly 5,000 artworks. Enjoy an in-depth exploration of a selection of those artworks acquired by gift, bequest, or purchase support by special donors, as written by staff curators and guest editors over the years. Table of Contents KENOJUAK ASHEVAK Kenojuak Ashevak (ken-OH-jew-ack ASH-uh-vac), one of the most well-known Inuit artists, was a pioneering force in modern Inuit art. Ashevak grew up in a semi-nomadic hunting family and made art in various forms in her youth. However, in the 1950s, she began creating prints. In 1964, Ashevak was the subject of the Oscar-nominated documentary, Eskimo* Artist: Kenojuak, which brought her and her artwork to Canada’s—and the world’s—attention. Ashevak was also one of the most successful members of the Kinngait Co-operative, also known as the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative, established in 1959 by James Houston, a Canadian artist and arts administrator, and Kananginak Pootoogook (ka-nang-uh-nak poo-to-guk), an Inuit artist. The purpose of the co-operative is the same as when it was founded—to raise awareness of Inuit art and ensure indigenous artists are compensated appropriately for their work in the Canadian (and global) art market. Ashevak’s signature style typically featured a single animal on a white background. Inspired by the local flora and fauna of the Arctic, Ashevak used bold colors to create dynamic, abstract, and stylized images that are devoid of a setting or fine details. -

November 5, 2009

ATTACHMENT 2 L ANDMARKSLPC 01-07-10 Page 1 of 18 P RESERVATION C OMMISSION Notice of Decision MEETING OF: November 5, 2009 Property Address: 2525 Telegraph Avenue (2512-16 Regent Street) APN: 055-1839-005 Also Known As: Needham/Obata Building Action: Landmark Designation Application Number: LM #09-40000004 Designation Author(s): Donna Graves with Anny Su, John S. English, and Steve Finacom WHEREAS, the proposed landmarking of 2525 Telegraph Avenue, the Needham/Obata Building, was initiated by the Landmarks Preservation Commission at its meeting on February 5, 2009; and WHEREAS, the proposed landmarking of the Needham/Obata Building is exempt from CEQA pursuant to Section 15061.b.3 (activities that can be seen with certainty to have no significant effect on the environment) of the CEQA Guidelines; and WHEREAS, the Landmarks Preservation Commission opened a public hearing on said proposed landmarking on April 2, 2009, and continued the hearing to May 7, 2009, and then to June 4, 2009; and WHEREAS, during the overall public hearing the Landmarks Preservation Commission took public testimony on the proposed landmarking; and WHEREAS, on June 4, 2009, the Landmarks Preservation Commission determined that the subject property is worthy of Landmark status; and WHEREAS, on July 9, 2009, following release of the Notice of Decision (NOD) on June 29, 2009, the property owner Ali Elsami submitted an appeal requesting that the City Council overturn or remand the Landmark decision; and WHEREAS, on September 22, 2009, the City Council considered Staff’s -

Andreas Schmid Interview Transcript

www.china1980s.org INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT ANDREAS SCHMID Interviewer: Jane DeBevoise, Anthony Yung Date: 27 Apr 2008 Duration: about 2 hours Location: Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong Question (Q): Why did you go to China? Where you and what were you doing? Who are some of the artists that you encountered and what do you think about them? What were the artists reading and what are your comments on those materials? Andreas Schmid (AS): I graduated from the Art Academy in Stuttgart in 1981, studying painting. My paintings were, at that time, very different from German painters like Kiefer in that they always have free space, and transparency of layers of space in them. I painted with oil and acrylic, and it was different from my colleagues/contemporaries. I became interested in the idea of space, of Chinese Art, classical Chinese art, like Ni Zan [倪赞] in the fourteenth century. Then I went to Cologne and saw a collection of Japanese Buddhist writings collected by Seiko Kono , abbot of the Daian-ji temple in Nara City , Japan. I would like to know the line from another side, because lines played the most important role graphically in my paintings. So I tried contacting organizations that would support me, and they informed me there was only one woman who went to China as an artist from Germany with the support of the German exchange service. I went to see her, and she had studied in Hangzhou one year ago at that time (1980). She studied birds and flowers painting. She told me, if you want to do this, you should go to China, it is interesting. -

Oral History Interview with Guy Anderson, 1983 February 1-8

Oral history interview with Guy Anderson, 1983 February 1-8 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Interview This transcript is in the public domain and may be used without permission. Quotes and excerpts must be cited as follows: Oral history interview with Guy Anderson, 1983 February 1-8, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Oral History Interview with Guy Anderson Conducted by Martha Kingsbury At La Conner, Washington 1983 February 1 & 8 GA: GUY ANDERSON MK: MARTHA KINGSBURY [Part 1] GA: Now that it is spring and February and I suppose it's a good time to talk about great things. I know the sun's out, the caterpillars and things coming out soon; but talking about the art scene, I have been reading a very interesting thing that was sent to me, once again, by Wesley Wehrÿ-- the talk that Henry Geldzahler gave to Yale, I think almost a year ago, about what he felt about the state of the New York scene, and the scene of art, generally speaking in the world. He said some very cogent things all through it, things that I think probably will apply for quite a long time, particularly to those people and a lot of young people who are so interested in the arts. Do you want to see that? MK: Sure. [Break in tape] MK: Go ahead. -

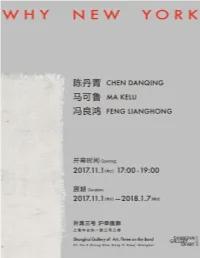

WHY-NEW-YORK-Artworks-List.Pdf

“Why New York” 是陈丹青、马可鲁、冯良鸿三人组合的第四次展览。这三位在中国当代艺术的不同阶 段各领风骚的画家在1990年代的纽约聚首,在曼哈顿和布鲁克林既丰饶又严酷的环境中白手起家,互 相温暖呵护,切磋技艺。到了新世纪,三人不约而同地回到中国,他们不忘艺术的初心,以难忘的纽约 岁月为缘由,频频举办联展。他们的组合是出于情谊,是在相互对照和印证中发现和发展各自的面目, 也是对艺术本心的坚守和砥砺。 不同于前几次带有回顾性的展览,这一次三位艺术家呈现了他们阶段性的新作。陈丹青带来了对毕加 索等西方艺术家以及中国山水及书法的研究,他呈现“画册”的绘画颇具观念性,背后有复杂的摹写、转 译、造型信息与图像意义的更替演化等话题。马可鲁的《Ada》系列在“无意识”中蕴含着规律,呈现出 书写性,在超越表面的技巧和情感因素的画面中触及“真实的自然”。冯良鸿呈现了2012年以来不同的 几种方向,在纯色色域的覆盖与黑白意境的推敲中展现视觉空间的质感。 在为展览撰写的文章中,陈丹青讲述了在归国十余年后三人作品中留有的纽约印记。这三位出生于上海 的画家此次回归家乡,又一次的聚首凝聚了岁月的光华,也映照着他们努力前行的年轻姿态。 “Why New York” marks the fourth exhibition of the artists trio, Chen Danqing, Ma Kelu and Feng Lianghong. Being the forerunners at the various stages in the progress of Chinese contemporary art, these artists first met in New York in the 1990s. In that culturally rich yet unrelenting environment of Manhattan and Brooklyn, they single-handedly launched their artistic practice, provided camaraderie to each other and exchanged ideas about art. In the new millennium, they’ve returned to China respectively. Bearing in mind their artistic ideals, their friendship and experiences of New York reunite them to hold frequent exhibitions together. With this collaboration built on friendship, they continue to discover and develop one’s own potential through the mirror of the others, as they persevere and temper in reaching their ideals in art. Unlike the previous retrospective exhibitions, the artists present their most recent works. Chen Danqing’s study on Picasso and other Western artists along with Chinese landscape painting and calligraphy is revealed in his conceptual painting “Catalogue”, a work that addresses the complex notions of drawing, translation, compositional lexicon and pictorial transformation. Ma Kelu’s “Ada” series embodies a principle of the “unconscious”, whose cursive and hyper expressive techniques adroitly integrates with the emotional elements of the painting to render “true nature”. -

CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN PAINTING and SCULPTURE 1969 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Js'i----».--:R'f--=

Arch, :'>f^- *."r7| M'i'^ •'^^ .'it'/^''^.:^*" ^' ;'.'>•'- c^. CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN PAINTING AND SCULPTURE 1969 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign jS'i----».--:r'f--= 'ik':J^^^^ Contemporary American Painting and Sculpture 1969 Contemporary American Painting and Sculpture DAVID DODD5 HENRY President of the University JACK W. PELTASON Chancellor of the University of Illinois, Urbano-Champaign ALLEN S. WELLER Dean of the College of Fine and Applied Arts Director of Krannert Art Museum JURY OF SELECTION Allen S. Weller, Chairman Frank E. Gunter James R. Shipley MUSEUM STAFF Allen S. Weller, Director Muriel B. Christlson, Associate Director Lois S. Frazee, Registrar Marie M. Cenkner, Graduate Assistant Kenneth C. Garber, Graduate Assistant Deborah A. Jones, Graduate Assistant Suzanne S. Stromberg, Graduate Assistant James O. Sowers, Preparator James L. Ducey, Assistant Preparator Mary B. DeLong, Secretary Tamasine L. Wiley, Secretary Catalogue and cover design: Raymond Perlman © 1969 by tha Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois Library of Congress Catalog Card No. A48-340 Cloth: 252 00000 5 Paper: 252 00001 3 Acknowledgments h.r\ ^. f -r^Xo The College of Fine and Applied Arts and Esther-Robles Gallery, Los Angeles, Royal Marks Gallery, New York, New York California the Krannert Art Museum are grateful to Marlborough-Gerson Gallery, Inc., New those who have lent paintings and sculp- Fairweother Hardin Gallery, Chicago, York, New York ture to this exhibition and acknowledge Illinois Dr. Thomas A. Mathews, Washington, the of the artists, Richard Gallery, Illinois cooperation following Feigen Chicago, D.C. collectors, museums, and galleries: Richard Feigen Gallery, New York, Midtown Galleries, New York, New York New York ACA Golleries, New York, New York Mr. -

Antonio Prieto; » Julio Aè Pared 30 a Craftsman5 Ipko^Otonmh^

Until you see and feel Troy Weaving Yarns . you'll find it hard to believe you can buy such quality, beauty and variety at such low prices. So please send for your sample collection today. and Textile Company $ 1.00 brings you a generous selection of the latest and loveliest Troy quality controlled yarns. You'll find new 603 Mineral Spring Avenue, Pawtucket, R. I. 02860 pleasure and achieve more beautiful results when you weave with Troy yarns. »««Él Mm m^mmrn IS Dialogue .n a « 23 Antonio Prieto; » Julio Aè Pared 30 A Craftsman5 ipKO^OtONMH^ IS«« MI 5-up^jf à^stoneware "iactogram" vv.i is a pòìnt of discussion in Fred-Schwartz's &. Countercues A SHOPPING CENTER FOR JEWELRY CRAFTSMEN at your fingertips! complete catalog of... TOOLS AND SUPPLIES We've spent one year working, compiling and publishing our new 244-page Catalog 1065 ... now it is available. In the fall of 1965, the Poor People's Corporation, a project of the We're mighty proud of this new one... because we've incor- SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), sought skilled porated brand new never-before sections on casting equipment, volunteer craftsmen for training programs in the South. At that electroplating equipment and precious metals... time, the idea behind the program was to train local people so that they could organize cooperative workshops or industries that We spent literally months redesigning the metals section . would help give them economic self-sufficiency. giving it clarity ... yet making it concise and with lots of Today, PPC provides financial and technical assistance to fifteen information.. -

Adrian Saxe by Elaine Levin

October 1993 1 William Hunt.................................... Editor Ruth C. Butler ................Associate Editor Robert L. Creager..................... Art Director Kim Nagorski..... .............Assistant Editor Mary Rushley ............... Circulation Manager Mary E. Beaver ....Assistant Circulation Manager Connie Belcher .......Advertising Manager Spencer L. Davis .......................... Publisher Editorial, Advertising and Circulation Offices 1609 Northwest Boulevard Post Office Box 12448 Columbus, Ohio 43212 (614) 488-8236 FAX (614) 488-4561 Ceramics Monthly (ISSN 0009-0328) is pub lished monthly except July and August by Profes sional Publications, Inc., 1609 Northwest Bou levard, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Second Class postage paid at Columbus, Ohio. Subscription Rates: One year $22, two years $40, three years $55. Add $10 per year for subscriptions outside the U.S.A. In Canada, also add GST (registration number R123994618). Change of Address:Please give us four weeks advance notice. Send the magazine address label as well as your new address to: Ceramics Monthly, Circulation Offices, Post Office Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Contributors: Manuscripts, announcements, news releases, photographs, color separations, color transparencies (including 35mm slides), graphic illustrations and digital TIFF or EPS im ages are welcome and will be considered for publication. Mail submissions to Ceramics Monthly, Post Office Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. We also accept unillustrated mate rials faxed to (614) 488-4561. Writing and Photographic Guidelines:A book let describing standards and procedures for sub mitting materials is available upon request. Indexing:An index of each year’s articles appears in the December issue. Additionally, Ceramics Monthly articles are indexed in the Art Index. Printed, on-line and CD-ROM (computer) index ing is available through Wilsonline, 950 Univer sity Avenue, Bronx, New York 10452; and from Information Access Company, 362 Lakeside Drive, Forest City, California 94404. -

HE MAKANA the Gertrude Mary Joan Damon Haig Collection of Hawaiian Art, Paintings and Prints Opens First Friday, Dec. 6, 2013

December 2013 HE MAKANA DECEMBER The Gertrude Mary Joan Damon FREE EVENTS Haig Collection Of Hawaiian Art, AT HISAM The public is invited to these free Paintings and Prints Opens First events for December 2013 to be held at the Hawai‘i State Art Mu- Friday, Dec. 6, 2013 seum in the No.1 Capitol District Building at 250 South Hotel Street he Gertrude Mary Joan Damon ing lands, an interest her children in downtown Honolulu. See feature Haig Collection of Hawaiian inherited. stories and photos of these events TArt, Paintings, and Prints is a Forty-three works of art-small in this enewsletter. Not subscribed distinguished collection of traditional objects, paintings, and prints collected to eNews? Join here for monthly arts of Hawai’i, over thirty years updates. paintings of by a keen-eyed First Friday Hawai’i, and single donor He Makana exhibit opening prints of Hawai’i comprise this Friday, December 6, 2013 presented to the important exhibi- 6-9 p.m. state of Hawaii in tion that opens to Celebrate the unveiling of the honor of the life the public at the Gertrude Mary Joan Damon Haig of Gertrude Mary Hawai’i State Art Collection of Hawaiian Art, Paintings, Joan Damon Museum on First and Prints. Haig. Friday, December First Friday In the Hawai- 6, 2013 from Holiday Harp ian language, He Waimea Canyon, Kauai by D. Howard Hitchcock 6:00 to 9:00 p.m. Friday, December 6, 2013 Makana means 1909, oil on canvas Perceptive and 6-9 p.m. A Gift, referring knowledgeable, HiSAM favorite Ruth Freedman to the generous the donor focused returns to weave holiday magic with gifting of the the core of the classic Christmas tunes and harp collection to the collection on the standards. -

Hilda Morris

HILDA MORRIS Born 1911, New York, NY Died 1991, Portland, OR EDUCATION AND AWARDS Cooper Union School of Art and Architecture, New York, NY 1932-34 Arts Students League of New York, NY 1934-35 Study with Comcetta Scaravaglione, New York, NY 1935-36 Ford Foundation Fellowship, one of ten selected 1960 Ninth Annual Governor’s Arts Award, Oregon 1985 ONE-PERSON EXHIBITIONS The Laura Russo Gallery, Portland, OR 1988, 2006 “Hilda Morris: A Retrospective,” Portland Art Museum, Portland, OR 2006 Foster/White Gallery, Seattle, WA 1990 The Ochi Fine Art Gallery, Boise, ID 1988 The Kraushaar Gallery, New York, NY 1987 The Portland Art Museum, OR 1946, 1955, 1972, 1974, 1977, 1984 The Fountain Gallery of Art, Portland, OR 1961, 1962, 1964, 1971, 1974, 1980, 1984 Woodside/Braseth Gallery, Seattle, WA 1968, 1972, 1975, 1978, 1981, 1987 Reed College, Portland, OR 1969, 1972, 1980 Gordon Woodside Galleries, Seattle, WA 1967, 1968, 1972, 1978 Triangle Gallery, San Francisco, CA 1974, 1976 University of Rochester Memorial Art Gallery, Rochester, NY 1976 Museum of Art, Tacoma, WA 1970 Albina Art Center, Portland, OR 1969 Salt Lake Art Center, UT 1963 University of Puget Sound, Tacoma, WA 1961 Otto Seligman Gallery, Seattle, WA 1955, 1957, 1960 Barone Gallery, New York, NY 1958 University of Oregon Museum of Art, Eugene, OR 1947 GROUP EXHIBITIONS “In Passionate Pursuit: The Arlene and Harold Schnitzer Collection and Legacy,” Portland Art Museum, 805 NORTHWEST TWENTY-FIRST AVE., PORTLAND, OR 97209 (503) 226-2754 HILDA MORRIS page 2 Portland, OR 2014-2015 “Creating the New Northwest: Selections from the Herb and Lucy Pruzan Collection,” Tacoma Art Museum, Tacoma, WA 2013 “Living Legacies: JSMA at 80,” Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 2013 “Early Northwest Artists: Works from Estates and Private Collections,” The Laura Russo Gallery, Portland, OR 2013 “Provenance: In Honor of Arlene Schnitzer,” Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, Univ of Oregon, Eugene, OR 2012 “Museion,” Douglas F.