A Century of Change on the Lindsey Marshland Marshchapel 1540 – 1640

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Groundwater in Jurassic Carbonates

Groundwater in Jurassic carbonates Field Excursion to the Lincolnshire Limestone: Karst development, source protection and landscape history 25 June 2015 Tim Atkinson (University College London) with contributions from Andrew Farrant (British Geological Survey) Introduction 1 The Lincolnshire Limestone is an important regional aquifer. Pumping stations at Bourne and other locations along the eastern edge of the Fens supply water to a large population in South Lincolnshire. Karst permeability development and rapid groundwater flow raise issues of groundwater source protection, one of themes of this excursion. A second theme concerns the influence of landscape development on the present hydrogeology. Glacial erosion during the Middle Pleistocene re-oriented river patterns and changed the aquifer’s boundary conditions. Some elements of the modern groundwater flow pattern may be controlled by karstic permeability inherited from pre-glacial conditions, whereas other flow directions are a response to the aquifer’s current boundary conditions. Extremely high permeability is an important feature in part of the confined zone of the present-day aquifer and the processes that may have produced this are a third theme of the excursion. The sites to be visited will demonstrate the rapid groundwater flow paths that have been proved by water tracing, whereas the topography and landscape history will be illustrated by views during a circular tour from the aquifer outcrop to the edge of the Fenland basin and back. Quarry exposures will be used to show the karstification of the limestone, both at outcrop and beneath a cover of mudrock. Geology and Topography The Middle Jurassic Lincolnshire Limestone attains 30 m thickness in the area between Colsterworth and Bourne and dips very gently eastwards. -

Keep Connected Newsletter Jun 21

Keep Connected June 2021 opening up again, we have included some of the activities we have been advised are restarting. If anyone has anything to add to this please W�lc��� let us know and we can feature to the June edition of the Keep Connected newsletter it in our August newsletter. T.E.D has recently started a new friendship group - Ageing Without Children - you’ll find further information about this, over the page. 12th May 2021 saw the launch of our Mobile Outreach Project - bringing our charity directly to the community. We now have everything ready to start getting out and about with our bus. We’ll keep an up-to-date timetable of where we will be on our website: www.ageuk.org.uk/lindsey or call 01507 524242 and we can advise when we will be in your area. Our Easter well-being packs L�� Project Manager It was lovely to see so many of 1st -7th June is Volunteers’ you when we delivered our last Week, therefore we would like newsletter and well-being packs to say a big thank you to all our at the end of March. We hope wonderful volunteers. They are you enjoyed receiving the packs at the heart of our charity and as much as we enjoyed enable us to provide our delivering them. The packs were wonderful befriending service, beautifully decorated by the make much appreciated well- primary school children at being calls, work in our charity Fiskerton, Great Steeping and shops and help at activities, Scampton and I am sure you’ll friendship groups and lunch agree they did a great job. -

The London Gazette, August 13, 1869

4578 THE LONDON GAZETTE, AUGUST 13, 1869. For the county of Lancaster. Killingholme; Brewster, Reverend Herbert, South Hugh Perkins, Liverpool j George Scholfield, Kelsey; Burkinshaw, William, Binbrooke ; Bing- Liverpool; Thomas Earle, Liverpool; Maxwell ham, James, Thorganby; Cove, Reverend Edward, Hyslop Maxwell, Liverpool j John J. Myers, Thoresway; Deane, Reverend Francis Hugh, Liverpool and Huyton ; George H. Thompson, Stainton-le-Vale ; Davy, John, North Owersby ; Liverpool: Hugh Frederick Hornby, Liverpool; Davy, Edmund, Worlaby; Dauber, John, Brigg ; William Henry Maclean, Liverpool; Robert C. Prankish, Henry, Normanby; Frankish, William, Crosbie, Liverpool: Reverend Oswald Henry Great Limber ; Frankish, William, Kirmington ; Leycester Penrhyu, Bickerstaffe ; Hugh M'Elroy, Graburn, William John, Melton Ross; Johnson, Maghull; Thomas Luzmore, Maghull; Thomas Reverend Woodthorpe, Grainsby; Harward, Gardiner, Ormskirk ; William Parr, Lathom; Reverend Edwin Cuthbert, Market Rasen ; Hop- Stephen Hand, Waterloo; Thomas Pickering kins, Thomas Bonner, Great Limber ; Hopkins, Pick, Waterloo; George Tinley, Waterloo; Joseph, Brigg ; Kirkham, Joseph Rinder, Caistor; Benjamin Nicholson, Waterloo ; George Postle- Markhanv Reverend Charles Warren, Saxby; thwaite, Waterloo ; William Joseph Robinson, Moor, Reverend Alfred Edgar, Horkstow; Ran- Waterloo ; James Gordon, Great Crosby; William dall, Thomas, North Owersby; Raven. Robert, Henry Jones, Seaforth; Anthony Bower,. Sea- Little Limber ; Turner, John, Ulceby; Uppleby, forth ; Thomas Ridley, -

Pinfold Lane, Little Cawthorpe, Louth, LN11 8FB Asking Price: £289,950

Pinfold Lane, Little Cawthorpe, Louth, LN11 8FB Stylish Family Home | Generously Sized | Entrance Hall & W.C | Lounge |Dining Room | Breakfast Kitchen & Utility Room | Four Double Bedrooms | Family Bathroom | Driveway & Gardens | EPC Rating TBC | Asking Price: £289,950 Pinfold Lane, Little Cawthorpe, Louth, LOUNGE LN11 8FB 3.60m (11' 10") x 7.30m (23' 11") A generously sized lounge with a dual aspect uPVC We are delighted to offer or sale 'Rowes End', a double glazed windows to the front and rear, with contemporary and charming family home situated roman shutters to the rear elevation. A multi fuel within the desirable village of Little Cawthorpe, burner stands within an exposed brick fireplace on with modern and stylish decoration throughout. a stone hearth with a sold wooden mantle beam The property offers spacious and flexible living over. Radiators and a TV aerial point. accommodation throughout in a peaceful position, within walking distance of the popular Royal Oak pub and having beautiful countryside walks. Viewing is a must to save disappointment!! Internally the property briefly comprises a welcoming entrance hall with an under stairs cupboard and w.c, a good sized dual aspect lounge, dining room and a breakfast kitchen with a utility room off. To the first floor are four double bedrooms, the main bedroom with a dressing room and a family bathroom. Externally there is a driveway to the front with timber fencing and double gates, the rear gardens are raised with artificial grass and with decking areas for seating and a hot tub. ACCOMMODATION Under a quaint pitched oak framed porch through a composite door with an inset obscured glazed window to: ENTRANCE HALL A welcoming and light entrance hall with stairs leading to the first floor, under stairs storage cupboard, laminate flooring, vertical retro style radiator, uPVC double glazed rear entrance door. -

Our Resource Is the Gospel, and Our Aim Is Simple;

Bolingbroke Deanery GGr raappeeVViinnee MAY 2016 ISSUE 479 • Mission Statement The Diocese of Lincoln is called by God to faithful worship, confident discipleship and joyful service. • Vision Statement To be a healthy, vibrant and sustainable church, transforming lives in Greater Lincolnshire 50p 1 Bishop’s Letter Dear Friends, Many of us will have experienced moments of awful isolation in our lives, or of panic, or of sheer joy. The range of situations, and of emotions, to which we can be exposed is huge. These things help to form the richness of human living. But in themselves they can sometimes be immensely difficult to handle. Jesus’ promise was to be with his friends. Although they experienced the crushing sadness of his death, and the huge sense of betrayal that most of them felt in terms of their own abandonment of him, they also experienced the joy of his resurrection and the happiness of new times spent with him. They would naturally have understood that his promise to ‘be with them’ meant that he would not physically leave them. However, what Jesus meant when he said that they would not be left on their own was that the Holy Spirit would always be with them. It is the Spirit, the third Person of the Holy Trinity, that we celebrate during the month of May. Jesus is taken from us, body and all, but the Holy Spirit is poured out for us and on to us. The Feast of the Holy Spirit is Pentecost. It happens at the end of Eastertide, and thus marks the very last transition that began weeks before when, on Ash Wednesday, we entered the wilderness in preparation for Holy Week and Eastertide to come. -

Council Tax Factsheet 1.1 East Lindsey 2021-2022

East Lindsey 2021-2022 Council Tax Factsheet 1.1 Lincolnshire County Council, Police and Crime Commissioner for Lincolnshire & East Lindsey District Council Council Tax Information Budget Summary Local Policing Summary Contacting East Lindsey District Council Tel: 01507 601111 Web: www.e-lindsey.gov.uk Email: [email protected] Lincolnshire County Council County Offices, Newland, Lincoln LN1 1YL General enquiries: 01522 552222 Fax: 01522 516137 Email: [email protected] Minicom service: 01522 552055 Web: www.lincolnshire.gov.uk If you want any more information on the County Council’s budget for 2021/2022, email [email protected] or visit www.lincolnshire.gov.uk/finance Police and Crime Commissioner for Lincolnshire Deepdale Lane, Nettleham, Lincoln LN2 2LT Tel: 01522 947192 Email: [email protected] | Web: www.lincolnshire-pcc.gov.uk Lincolnshire Police General Enquiries Tel: 01522 532222 (your call may be recorded) | Emergencies: 999 and ask for police Minicom/textphone: 01522 558140 | Web: www.lincs.police.uk East Lindsey 2021-2022 Council Tax Factsheet 1.2 Here’s a summary of the 2021/22 budget: In recent years, the District Council has faced A Market Towns investment fund to help significant financial challenges, achieving savings support economic growth (building on the through new and more efficient ways of working existing programme of interventions along the which has included a new Strategic Alliance with coast, including the Towns Fund investment Boston Borough Council which will save the in Mablethorpe and Skegness, announced by Council £1.2m per year. Government in the Budget). The Council has this year increased its proportion Increased capital investment in Council of Council Tax by 3.37% - £4.95 per year – an assets to help generate more income, reduce extra 9.5p per week for a Band D property. -

LINCOLNSHIRE. F .Abmers-Continmd

F..AR. LINCOLNSHIRE. F .ABMERs-continmd. Mars hall John Jas.Gedney Hill, Wisbech Mastin Charles, Sutterton Fen, Boston Maplethorpe Jackson, jun. Car dyke, Marshal! John Thos. Tydd Gate, Wibbech 1Mastin Fredk. jun. Sutterton Fen, Boston Billinghay, Lincoln Marsball John Thos. Withern, Alford Mastin F. G. Kirkby Laythorpe, Sleafrd Maplethorpe Jn. Bleasby, Lrgsley, Lncln Marshall Joseph, .Aigarkirk, Boston Mastin John, Tumby, Boston Maplethorpe Jsph. Harts Grounds,Lncln Marbhall Joseph, Eagle, Lincoln Mastin William sen. Walcot Dales, Maplethorpe Wm. Harts Grounds,Lncln MarshalJJsph. The Slates,Raithby,Louth Tattershall Bridge, Linco·n Mapletoft J. Hough-on-the-Hill, Grnthm Marshall Mark,Drain side,Kirton,Boston Mastin Wm. C. Fen, Gedney, Ho"beach Mapletoft Robert, Nmmanton, Grar.thm Marshall Richard, Saxilby, Lincoln Mastin Wi!liam Cuthbert, jun. Walcot Mapletoft Wil'iam, Heckington S.O Marshall Robert, Fen, :Fleet, Holbeach Dales, Tattel"!lhall Bridge, Lincoln Mappin S. W.Manor ho. Scamp ton, Lncln Marshall Robert, Kral Coates, Spilsby Matthews James, Hallgate, Sutton St. Mapplethorpe William, Habrough S.O Marshall R. Kirkby Underwood, Bourne Edmunds, Wisbech Mapplethorpe William Newmarsh, Net- Marshal! Robert, Northorpe, Lincoln Maultby George, Rotbwell, Caistor tleton, Caistor Marshall Samuel, Hackthorn, Lincoln Maultby James, South Kelsey, Caistor March Thomas, Swinstead, Eourne Marshall Solomon, Stewton, Louth Maw Allan, Westgate, Doncaster Marfleet Mrs. Ann, Somerton castle, Marshall Mrs. S. Benington, Boston Maw Benj. Thomas, Welbourn, Lincoln Booth by, Lincoln Marshall 'fhomas, Fen,'fhorpe St.Peter, Maw Edmund Hy. Epworth, Doncaster Marfleet Charles, Boothby, Lincoln Wainfleet R.S.O Maw George, Messingham, Brigg Marfleet Edwd. Hy. Bassingbam, Lincln Marshall T. (exors. of), Ludboro', Louth Maw George, Wroot, Bawtry Marfleet Mrs. -

Northolme Farmhouse, Northolme Cottage, Former Alvingham Farm Shop, Cafe and Land, Alvingham

Northolme Farmhouse, Northolme Cottage, Former Alvingham Farm Shop, Cafe and Land, Alvingham Northolme Farm North End, Alvingham, Nr Louth, LN11 0QH A chance to live and work on a privately situated equestrian/hobby farm with a former Farm Shop and Cafe and great potential for further conversion of outbuildings for business, holiday or residential use (STP); all set within 7.7 acres (STS) with a4/5 bedroom period farmhouse and a detached 3-bedroom cottage. Attractive 4/5 bedroom period farmhouse with 3 good reception rooms and a characterful Farmhouse h Kitchen Peaceful rural setting, positioned well back from the village lane along a lengthy driveway Former Farm Shop and Cafe building with a butchery and numerous cold storage rooms with a spacious parking and turning area opposite A range of outbuildings suitable to be used in conjunction with hobby farming or equestrian use and/or with great potential to convert into holiday, business or residential accommodation (STP) Land extending to7.7 acres (STS) to include 3 level grass paddocks A detached brick and pantile 3 bedroom cottage with a lawned garden and outbuildings, ideal to generate income as a rental property or equally for housing family or staff Ideally located for access to both the market town of Louth and the Coast Sole Agents: Masons Rural and Equestrian Cornmarket, Louth, Lincolnshire LN11 9QD T 01507 350500 www.ruralproperty4sale.co.uk Situation This appealing rural setting is within easy commuting distance of Louth, the coast and the Humber bank. To drive to the property from Louth take Eastfield Road, turn left signposted Alvingham, at the t –junction turn right onto Alvingham road. -

In the Beginning SKIPWITHS

In the Beginning 16th to 18th century SKIPWITHS of Theddlethorpe, Manby, Grimoldby, Alvingham Lincolnshire, U.K. Introduction.......................................................................................................................... 2 Map of the Lincolnshire Marsh ............................................................................................ 4 Seven Generation Chart...................................................................................................... 5 First Generation................................................................................................................... 6 Second Generation (Children) ............................................................................................ 7 Third Generation (Grandchildren) ....................................................................................... 8 Fourth Generation (Great-Grandchildren)......................................................................... 11 Fifth Generation (Great Great-Grandchildren) .................................................................. 13 Sixth Generation (3x Great-Grandchildren) ...................................................................... 16 Appendix 1: Relationship to Skipworths of Sth Lindsey & Holland .................................. 17 Appendix 2: Relationship to the Skipwiths of Utterby ...................................................... 18 Appendix 3: Farming in Lincolnshire................................................................................ 19 -

Lincolnshire. Louth

DIRECI'ORY. J LINCOLNSHIRE. LOUTH. 323 Mary, Donington-upon-Bain, Elkington North, Elkington Clerk to the Commissioners of Louth Navigation, Porter South, Farforth with Maidenwell, Fotherby, Fulstow, Gay Wilson, Westgate ton-le-Marsh, Gayton-le-"\\'old, Grains by, Grainthorpe, Clerk to Commissioners of Taxes for the Division of Louth Grimblethorpe, Little Grimsby, Grimoldby, Hainton, Hal Eske & Loughborough, Richard Whitton, 4 Upgate lin,o1on, Hagnaby with Hannah, Haugh, Haugham, Holton Clerk to King Edward VI. 's Grammar School, to Louth le-Clay, Keddington, Kelstern, Lamcroft, Legbourne, Hospital Foundation & to Phillipson's & Aklam's Charities, Louth, Louth Park, Ludborough, Ludford Magna, Lud Henry Frederic Valentine Falkner, 34 Eastgate ford Parva, Mablethorpe St. Mary, Mablethorpe St. Collector of Poor Rates, Charles Wilson, 27 .Aswell street Peter, Maltby-le-Marsh, Manby, Marshchapel, Muckton, Collector of Tolls for Louth Navigation, Henry Smith, Ormsby North, Oxcombe, Raithby-cum-:.Vlaltby, Reston Riverhead North, Reston South, Ruckland, Saleby with 'fhores Coroner for Louth District, Frederick Sharpley, Cannon thorpe, Saltfleetby all Saints, Saltfleetby St. Clement, street; deputy, Herbert Sharpley, I Cannon street Salttleetby St. Peter, Skidbrook & Saltfleet, Somercotes County Treasurer to Lindsey District, Wm.Garfit,Mercer row North, Somercotes South, Stenigot, Stewton, Strubby Examiner of Weights & Measures for Louth district of with Woodthorpe, Swaby, 'fathwell, 'fetney, 'fheddle County, .Alfred Rippin, Eastgate thorpe All Saints, Theddlethorpe St. Helen, Thoresby H. M. Inspector of Schools, J oseph Wilson, 59 Westgate ; North, Thoresby South, Tothill, Trusthorpe, Utterby assistant, Benjamin Johnson, Sydenham ter. Newmarket Waith, Walmsgate, Welton-le-Wold, Willingham South, Inland Revenue Officers, William John Gamble & Warwick Withcall, Withern, Worlaby, Wyham with Cadeby, Wyke James Rundle, 5 New street ham East & Yarborough. -

Latest Parish Newsletter

The Parish of Louth and Deanery of Louthesk Weekly notes and information for 3rd October 2021: Eighteenth Sunday after Trinitywww.teamparishoflouth.org.uk In all we do, we seek to live out Jesus’ command to draw close to the love of God in worship, and to share this by loving our neighbour Collect Prayer for the week Almighty and everlasting God, increase in us your gift of faith that, forsaking what lies behind and reaching out to that which is before, we may run the way of your commandments and win the crown of everlasting joy; through Jesus Christ your Son our Lord, who is alive and reigns with you, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. Amen Our churches: opening as places for prayer and reflection in our communities The Parish Church of Louth St James will be open between 10am and 4pm Monday to Saturday unless otherwise stated below. Please see pages 3 and 4 for details of other churches that are open for private prayer and public visits across the Deanery of Louthesk DIARY OF PRAYER & WORSHIP THIS WEEK… Services marked * are broadcast via www.facebook.com/louthchurch Sunday 3rd 9 30am HARVEST FESTIVAL at Great Carlton Eighteenth Sunday 9 30am HOLY COMMUNION at Covenham After Trinity 10am HARVEST FESTIVAL (EUCHARIST) at St James’* Golden Sheaves, Parker Hymns: 275; 254; 270; 271 (Common Praise) Genesis 2.18-24; Hebrews 1.1-4, 2.5-12; Mark 10.2-16 All things bright and beautiful, Rutter 10am HOLY COMMUNION at North Thoresby 10am MORNING SERVICE (Methodist) at Fulstow 10.30am MORNING SERVICE at Grimoldby 11 15am HOLY COMMUNION at Legbourne 12 30pm BAPTISM (Grace & Albert Whitehouse) at Ludford 2 30pm BAPTISM (Carter Collins) at Manby 3pm BAPTISM (Elsie Herbert) at Belleau 3pm BAPTISM (River Hickling) at St Michaels, Louth 6pm HARVEST FESTIVAL at Marshchapel 6pm EVENSONG at St James’* Ayleward Responses Psalm 126 Evening Service in E Minor, D. -

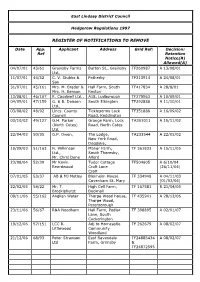

Register of Notifications to Remove

East Lindsey District Council Hedgerow Regulations 1997 REGISTER OF NOTIFICATIONS TO REMOVE Date App. Applicant Address Grid Ref: Decision: Ref Retention Notice(R) Allowed(A) 04/07/01 43/61 Grainsby Farms Barton St., Grainsby TF260987 A 13/08/01 Ltd., 11/07/01 44/52 C. V. Stubbs & Fotherby TF313914 A 24/08/01 Son 31/07/01 45/161 Mrs. M. Brader & Hall Farm, South TF417834 A 28/8/01 Mrs. H. Benson Reston 13/08/01 46/107 R. Caudwell Ltd., A18, Ludborough TF279963 A 10/09/01 04/09/01 47/159 G. & B. Dobson South Elkington TF292888 A 11/10/01 Ltd., 03/08/02 48/92 Lincs. County Ticklepenny Lock TF351888 A 16/09/02 Council Road, Keddington 03/10/02 49/127 G.H. Parker Grange Farm, Lock TA351011 A 15/11/02 (North Cotes) Road, North Cotes Ltd. 22/04/03 50/35 G.P. Owen, The Lodge, TA233544 A 22/05/02 New York Road, Dogdyke, 10/09/03 51/163 N. Wilkinson Manor Farm, TF 361833 A 15/11/05 Ltd., South Thoresby, Mr. Chris Done Alford 23/08/04 52/39 Mr Kevin Tudor Cottage TF504605 A 6/10/04 Beardwood Croft Lane (26/11/04) Croft 07/01/05 53/37 AB & MJ Motley Blenheim House TF 334948 A 04/11/03 Covenham St. Mary (01/03/04) 22/02/05 54/22 Mr. T. High Cell Farm, TF 167581 R 21/04/05 Brocklehurst Bucknall 09/11/06 55/162 Anglian Water Thorpe Wood house, TF 435941 A 28/12/06 Thorpe Wood, Peterborough 23/11/06 56/67 R&A Needham Hall Farm, Pedlar TF 398895 A 02/01/07 Lane, South Cockerington 19/12/06 57/151 LCC R.