Auder's Chronicles of Situa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joan Quinn Captured

Opening ReceptiOn: june 28, 7pm–10pm AdmissiOn is fRee Joan Quinn Captured Curated by Laura Whitcomb and organized by Brand Library Art Galleries panel discussions, talks and film screenings have been scheduled in conjunction with this gallery exhibition. Programs are free and are by reservation only. Tickets may be Joan Quinn Captured reserved at www.glendalearts.org. Join us for the opening reception on Saturday, June 28th, 7:00pm – 10:00pm. 6/28 EmErging LandscapE: 7/17 WarhoL/basquiat/quinn Los angeles 5:00pm film Jean Michel Basquiat: The exhibition ‘Joan Quinn Captured’ will 2:00pm panel Modern Art in Los Angeles: The Radiant Child showcase what is perhaps the largest portrait ‘Cool School’ Oral History Ed Moses 6:30pm panel Warhol & Basquiat: collection by contemporary artists in the world, 3:00PM film LA Suggested by the Art The Magazine of the 80s, Joan including such luminaries as Jean-Michel of Ed Ruscha Quinn’s work for Interview, the Basquiat, Shepard Fairey, Frank Gehry, Manipulator & Stuff Magazine; Robert Graham, David Hockney, Ed Ruscha, 4:30PM panel Los Angeles and the Contemporary Art Dawn Special Speaker Matthew Rolston Beatrice Wood and photographers Robert 7:00pm film Andy Warhol: Mapplethorpe, Helmut Newton, Matthew Rolston and Arthur A Documentary Film Tress. For the first time, this portrait collection will be exhibited in 7/3 EtErnaL rEturn collaboration with renowned works of the artists encouraging a 5:00pm film Beatrice Wood: Mama of Dada dialogue between the portraits and specific artist movements. The 7/24 don bachardy exhibition will also portray the world Joan Agajanian Quinn captured 6:30pm film Duggie Fields’ Jangled 6:00pm film Chris & Don: A Love Story as editor for her close friend Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine, 7:00pm talk Guest Artist Duggie Fields 7:30pm film Memories of Berlin: along with contributions to some of the most important fanzines of 8:00pm film The Great Wen the 1980’s that are proof of her role as a critical taste maker of her The Twilight of Weimar Culture time. -

Nov 2014 Dummy.Indd

NOVEMBERJULY 20102014 •• TAXITAXI INSIDERINSIDER •• PAGEPAGE 11 INSIDER VOL. 15, NO. 11 “The Voice of the NYC Transportation Industry.” NOVEMBER 2014 Letters Start on Page 3 EDITORIAL • By David Pollack Insider News Page 5 • Taxi Drivers and Ebola Updated Relief Stands Thankfully there is a radio show where you can Taxi Dave (that’s me!) not only had the Chairwoman get fi rst hand information needed to answer any of of the TLC, Meera Joshi discuss fears of the Ebola Page 6 your questions whether industry related or even virus, but I had Dr. Jay Varma, a spokesperson from • health related. the NYC Department of Health answering all ques- Taxi Attorney Before we get into Ebola, TLC Chair- tions that drivers brought to “Taxi Dave’s” By Michael Spevack woman Joshi stated that the TLC will attention. How does Ebola spread? What be sending out warning letters to drivers is the best means of prevention and pro- Page 7 instead of summonses for a red light tection? • camera offense. “Vision Zero is not Chairwoman Joshi stated, “Thank you How I Became A Star about penalties,” she stated. To hear this for reaching out to the Department of By Abe Mittleman and much more, listen to this link: http:// Health. The myth of how Ebola spreads is www.wor710.com/media/podcast-the- spreading incredibly faster than the actual Page 15 taxi-dave-show-TaxiInsider/the-taxi-dave- disease ever could. It is really important to • show-102614-25479519/ separate facts from fi ction and the Depart- Street Talk Folks, if you want fi rst hand infor- ment of Health has been doing an amazing By Erhan Tuncel mation, every Sunday evening at 8:00 job in getting that message out there and PM listen to WOR-710 radio to TAXI DAVE. -

Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers

Catalog 10 Flyers + Boo-hooray May 2021 22 eldridge boo-hooray.com New york ny Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers Boo-Hooray is proud to present our tenth antiquarian catalog, exploring the ephemeral nature of the flyer. We love marginal scraps of paper that become important artifacts of historical import decades later. In this catalog of flyers, we celebrate phenomenal throwaway pieces of paper in music, art, poetry, film, and activism. Readers will find rare flyers for underground films by Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith, and Andy Warhol; incredible early hip-hop flyers designed by Buddy Esquire and others; and punk artifacts of Crass, the Sex Pistols, the Clash, and the underground Austin scene. Also included are scarce protest flyers and examples of mutual aid in the 20th Century, such as a flyer from Angela Davis speaking in Harlem only months after being found not guilty for the kidnapping and murder of a judge, and a remarkably illustrated flyer from a free nursery in the Lower East Side. For over a decade, Boo-Hooray has been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections and look forward to inviting you back to our gallery in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Catalog prepared by Evan Neuhausen, Archivist & Rare Book Cataloger and Daylon Orr, Executive Director & Rare Book Specialist; with Beth Rudig, Director of Archives. Photography by Evan, Beth and Daylon. -

Recent Publications in Music 2010

Fontes Artis Musicae, Vol. 57/4 (2010) RECENT PUBLICATIONS IN MUSIC R1 RECENT PUBLICATIONS IN MUSIC 2010 Compiled and edited by Geraldine E. Ostrove On behalf of the Pour le compte de Im Auftrag der International l'Association Internationale Internationalen Vereinigung Association of Music des Bibliothèques, Archives der Musikbibliotheken, Libraries Archives and et Centres de Musikarchive und Documentation Centres Documentation Musicaux Musikdokumentationszentren This list contains citations to literature about music in print and other media, emphasizing reference materials and works of research interest that appeared in 2009. It includes titles of new journals, but no journal articles or excerpts from compilations. Reporters who contribute regularly provide citations mainly or only from the year preceding the year this list is published in Fontes Artis Musicae. However, reporters may also submit retrospective lists cumulating publications from up to the previous five years. In the hope that geographic coverage of this list can be expanded, the compiler welcomes inquiries from bibliographers in countries not presently represented. CONTRIBUTORS Austria: Thomas Leibnitz New Zealand: Marilyn Portman Belgium: Johan Eeckeloo Nigeria: Santie De Jongh China, Hong Kong, Taiwan: Katie Lai Russia: Lyudmila Dedyukina Estonia: Katre Rissalu Senegal: Santie De Jongh Finland: Tuomas Tyyri South Africa: Santie De Jongh Germany: Susanne Hein Spain: José Ignacio Cano, Maria José Greece: Alexandros Charkiolakis González Ribot Hungary: Szepesi Zsuzsanna Tanzania: Santie De Jongh Iceland: Bryndis Vilbergsdóttir Turkey: Paul Alister Whitehead, Senem Ireland: Roy Stanley Acar Italy: Federica Biancheri United Kingdom: Rupert Ridgewell Japan: Sekine Toshiko United States: Karen Little, Liza Vick. The Netherlands: Joost van Gemert With thanks for assistance with translations and transcriptions to Kersti Blumenthal, Irina Kirchik, Everett Larsen and Thompson A. -

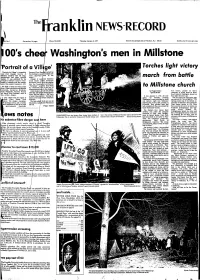

T"° Anklin News-Record

T"° anklin news-recorD one section, 24 pages / Phone 725-3300 Thursday, January 6, 1977 Second class postage paid at Princeton, N.J. 08540 I!,No. 1 $4.50 a year/t5 cents per copy O0’s chee Washington’s men in Millstone a ViI ge’ Torches light victory 0Portrait"Portrait of a Village"is a carefullyof Somerset Court HouLppreaehed the segched 50-page hislory of Revolutionary Millstone, complete with 100 .maps, most important photographs and other graphic county’." march from battle iisplays. It was published by the Chapter II deal Somerset mrough’s Historic District Com- Court House ant American nissinn to coincide with the reenact- Revolution,and it’ ~ on this chapter nent of the events of January3, 1777. that the ial production The book is edited by Diane Jones "Turnabout" was Hap Heins to Millstone church ;tiney. Othercontributors are Marllyn Sr. contributed a in the way of information and s to this chapter. :antarella, Katharine Erickson, Otherchapters ¢LI with the periods by Peggy Roeske Van Doren, played by Terry 3rnce Marganoff, Patricia Nivlson Special Writer Jamieson, at whose house on River md Barrie Alan Peterson, each of who.n wrote a chapter. times. The final c is "250 Years Road General Washington stayed on of Local ChurchI tracing the It was January 3, 1T/7, all over that night 200 years ago. ’ ~pter I deals with the origins of history of the DuReform Church in again. On Monday evening The play gave the imnression that ~erset Court House tnow Millstone. Washingten’s army marched by torch war was not all *’fun and games."The The chapter concludes: The booksells can be and lantern light into Millstone opening scene was of the British ca- forge, farms, and a variety obtained b following the victory that morningat cups(ion of Millstone (then Somerset all industriesas wellas its legal 359-1361. -

D2492609215cd311123628ab69

Acknowledgements Publisher AN Cheongsook, Chairperson of KOFIC 206-46, Cheongnyangni-dong, Dongdaemun-gu. Seoul, Korea (130-010) Editor in Chief Daniel D. H. PARK, Director of International Promotion Department Editors KIM YeonSoo, Hyun-chang JUNG English Translators KIM YeonSoo, Darcy PAQUET Collaborators HUH Kyoung, KANG Byeong-woon, Darcy PAQUET Contributing Writer MOON Seok Cover and Book Design Design KongKam Film image and still photographs are provided by directors, producers, production & sales companies, JIFF (Jeonju International Film Festival), GIFF (Gwangju International Film Festival) and KIFV (The Association of Korean Independent Film & Video). Korean Film Council (KOFIC), December 2005 Korean Cinema 2005 Contents Foreword 04 A Review of Korean Cinema in 2005 06 Korean Film Council 12 Feature Films 20 Fiction 22 Animation 218 Documentary 224 Feature / Middle Length 226 Short 248 Short Films 258 Fiction 260 Animation 320 Films in Production 356 Appendix 386 Statistics 388 Index of 2005 Films 402 Addresses 412 Foreword The year 2005 saw the continued solid and sound prosperity of Korean films, both in terms of the domestic and international arenas, as well as industrial and artistic aspects. As of November, the market share for Korean films in the domestic market stood at 55 percent, which indicates that the yearly market share of Korean films will be over 50 percent for the third year in a row. In the international arena as well, Korean films were invited to major international film festivals including Cannes, Berlin, Venice, Locarno, and San Sebastian and received a warm reception from critics and audiences. It is often said that the current prosperity of Korean cinema is due to the strong commitment and policies introduced by the KIM Dae-joong government in 1999 to promote Korean films. -

N7637 Pigeon Rd

1 - N7637 Pigeon Rd. – Lots of baby & toddler toys (standing and ride-on toys, rocking horse electronic w/music & lights). Lots of girls clothes (newborn to 24 mo/2T most purchased new 2-5 years ago). Glider & footstool barely used. 5 wood doors with skeleton key locks. Set of 3 glass-top tables (2 end & 2 coffee) metal painted cream/tan. Men’s sweaters, sweatshirts, jeans (sz L), women’s sweaters, jeans, shirts (sz M) & pants (sz 6-9). Scrubs sets all occasions like new/fun patterns (sz S-M), women’s jackets, clothing, etc (sz S). 2 high-back bar stools, chandelier & light fixtures & misc items for home. Tornado foosball table like new (will not physically be at the sale but will have a photo and can arrange to look at). Children’s board books, girl crib set w/mobile, comforter (never used), sheets, dust ruffle, bumper pads pink butterflies. 2 crib mattresses, waterproof mattress protectors, crib sheets, railing padded protector, Safety 1 st baby gate (white plastic). Several white sconces, various tools, girl 2-wheel bike Disney Princes 14”, jogging & other strollers, 2 diaper champs, pizza oven, outdoor infant dolphin swing, mesh safety rails, 2 potty chairs, Sony baby monitors, & more! 2 - N7663 Pigeon Rd. – Baby boy clothes, chair, toys, costumes, home décor, maternity clothes and more. All priced to sell! 3 - N7770 State Park Rd. – 3-Family Rummage Sale: Two 10 ft. x 20 ft. tan colored party tents, “This End Up” loveseat, couch and desk set-rustic looking and built to last. DVDs albums, golf clubs, bar lights, metal poles for bird houses, graduation decorations (orange, black & purple), household and décor items, queen size comforter with pillow shams, drapes and valances, real estate items including realtor motivational tapes/CDs, display stands, etc. -

Gerard Malanga Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt0q2nc3z3 No online items Finding Aid of the Gerard Malanga Papers Processed by Wendy Littell © 2004 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid of the Gerard 2032 1 Malanga Papers Finding Aid of the Gerard Malanga Papers UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Los Angeles, CA Processed by: Wendy Littell, Winter 1974 Encoded by: ByteManagers using OAC finding aid conversion service specifications Encoding supervision and revision by: Caroline Cubé Edited by: Josh Fiala, May 2004 © 2004 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Gerard Malanga Papers, Date (inclusive): 1963-1979 Collection number: 2032 Creator: Malanga, Gerard Extent: 30 boxes (15 linear ft.) 1 oversize box Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Department of Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Abstract: Gerard Joseph Malanga (1943- ) was a cinematographer, executive producer, casting director, and actor in Andy Warhol Films (1963-70), had several one-man photographic exhibitions, and was a poet. The collection consists of correspondence, literary manuscripts, periodicals, books, subject files, photographs, posters, and ephemera. Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Language: English. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Advance notice required for access. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. -

Stroboscopic: Andy Warhol and the Exploding Plastic Inevitable Homay King Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College History of Art Faculty Research and Scholarship History of Art 2014 Stroboscopic: Andy Warhol and the Exploding Plastic Inevitable Homay King Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Custom Citation H. King, "Stroboscopic: Andy Warhol and the Exploding Plastic Inevitable," Criticism 56.3 (Fall 2014): 457-479. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs/72 For more information, please contact [email protected]. King 6/15/15 Page 1 of 30 Stroboscopic:+Andy+Warhol+and+the+Exploding+Plastic+Inevitable+ by+Homay+King,+Associate+Professor,+Department+of+History+of+Art,+Bryn+Mawr+College+ Published+in+Criticism+56.3+(Fall+2014)+ <insert+fig+1+near+here>+ + Pops+and+Flashes+ At+least+half+a+dozen+distinct+sources+of+illumination+are+discernible+in+Warhol’s+The+ Velvet+Underground+in+Boston+(1967),+a+film+that+documents+a+relatively+late+incarnation+of+ Andy+Warhol’s+Exploding+Plastic+Inevitable,+a+multimedia+extravaganza+and+landmark+of+ the+expanded+cinema+movement+featuring+live+music+by+the+Velvet+Underground+and+an+ elaborate+projected+light+show.+Shot+at+a+performance+at+the+Boston+Tea+Party+in+May+of+ 1967,+with+synch+sound,+the+33\minute+color+film+combines+long+shots+of+the+Velvet+ -

100 Cans by Andy Warhol

Art Masterpiece: 100 Cans by Andy Warhol Oil on canvas 72 x 52 inches (182.9 x 132.1 cm) Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery Keywords: Pop Art, Repetition, Complimentary Colors Activity: 100 Can Collective Class Mural Grade: 5th – 6th Meet the Artist • Born Andrew Warhol in 1928 near Pittsburgh, Pa. to Slovak immigrants. His father died in a construction accident when Andy was 13 years old. • He is known as an American painter, film-maker, publisher and major figure in the pop art movement. • Warhol was a sickly child, his mom would give him a Hershey bar for every coloring book page he finished. He excelled in art and won a scholarship to college. • After college, he moved to New York City and became a magazine illustrator – became known for his drawings of shoes. His mother lived with him – they had no hot water, the bathtub was in the kitchen and had up to 20 cats living with them. Warhol ate tomato soup every day for lunch. Chandler Unified School District Art Masterpiece • In the 1960’s, he started to make paintings of famous American products such as soup cans, coke bottles, dollar signs & celebrity portraits. He became known as the Prince of Pop – he brought art to the masses by making art out of daily life. • Warhol began to use a photographic silk-screen process to produce paintings and prints. The technique appealed to him because of the potential for repeating clean, hard-edged shapes with bright colors. • Andy wanted to remove the difference between fine art and the commercial arts used for magazine illustrations, comic books, record albums or ad campaigns. -

I – Introduction

QUEERING PERFORMATIVITY: THROUGH THE WORKS OF ANDY WARHOL AND PERFORMANCE ART by Claudia Martins Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment for the degree of Master of Arts in Gender Studies CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2008 I never fall apart, because I never fall together. Andy Warhol The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back again CEU eTD Collection CONTENTS ILLUSTRATIONS..........................................................................................................iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.................................................................................................v ABSTRACT...................................................................................................................vi CHAPTER 1 - Introduction .............................................................................................7 CHAPTER 2 - Bringing the body into focus...................................................................13 CHAPTER 3 - XXI century: Era of (dis)embodiment......................................................17 Disembodiment in Virtual Spaces ..........................................................18 Embodiment Through Body Modification................................................19 CHAPTER 4 - Subculture: Resisting Ajustment ............................................................22 CHAPTER 5 - Sexually Deviant Bodies........................................................................24 CHAPTER 6 - Performing gender.................................................................................29 -

Andy Warhol Exhibit American Fare Summer Sets

NYC ® Monthly JULY 2015 JULY 2015 JULY NYC MONTHLY.COM VOL. 5 NO.7 VOL. AMERICAN FARE AMERICAN CUISINE AT ITS FINEST SUMMER SETS HEADLINING ACTS YOU CAN'T MISS ANDY WARHOL EXHIBIT AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART B:13.125” T:12.875” C M Y K S:12.75” The Next Big Thing Is Here lated. Appearance of device may vary. B:9.3125” S:8.9375” T:9.0625” The world’s frst dual-curved smartphone display Available now. Learn more at Samsung.com/GS6 ©2015 Samsung Electronics America, Inc. and Galaxy S are trademarks of Co., Ltd. Screen images simu FS:6.3125” FS:6.3125” F:6.4375” F:6.4375” 304653rga03_HmptMnthy TL Project Title: US - GS6_2015_S5053 Job Number: S5053 Executive Creative Director: None E.C.D. C.D. A.C.D A.D. C.W. Creative Director: None Client: SAMSUNG Bleed: 13.125” x 9.3125” Associate Creative Director: None Media: MAGAZINE Trim 1: 12.875” x 9.0625” Art Director: None Photographer: None Trim 2: None Copywriter: None Art Buyer: None STUDIO PRODUCTION IA PRODUCER ACCOUNT EX. ART BUYER Illustrator: None Live: 12.75” x 8.9375” Print Production: None Insertion Date: None Gutter: 0.125” Studio Manager: None Account Executive: None Traffic: None Publications/Delivery Company: Hamptons Monthly FILE IS BUILT AT: 100% THIS PRINT-OUT IS NOT FOR COLOR. 350 West 39th Street New York, NY 10018 212.946.4000 Round: 1 Version: C PACIFIC DIGITAL IMAGE • 333 Broadway, San Francisco CA 94133 • 415.274.7234 • www.pacdigital.com Filename:304653rga03_HmptMnthy.pdf_wf02 Operator:SpoolServer Time:13:37:40 Colors:Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Black Date:15-05-06 NOTE TO RECIPIENT: This file is processed using a Prinergy Workflow System with an Adobe Postscript Level 3 RIP.