Rethinking Political Change - the Daily Show Model

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Daily Show På Persisk

10 # 08 25. februar 2011 Ideer We e ke n d av i s e n Humor som våben. Det satiriske show Parazit på Voice of America har et solidt tag i Irans enorme unge befolkning. Men det er bare ét af tegnene på, at eksilbefolkning og iransk opposition rykker stadig tættere sammen. The Daily Show på persisk Af METTE HEDEMAND SØLTOFT INTERESSEN for at undersøge forholdet Cand.mag. i persisk imellem den iranske diaspora og Iran afspejles i et stigende antal videnskabelige artikler, der ’Der er ingen bøsser i Iran’, erklærede også viser, at eksiliranerne generelt er bemær- præsident Ahmedinejad foran uni- kelsesværdigt veluddannede og ofte godt »versitetet i Columbia, et af verdens integrerede i de lande og samfund, de har slået mest respekterede universiteter.« sig ned i. Man kan registrere en udvikling i Saman Arbabi fra tv-showet Parazit holder mentaliteten i den ellers religiøst og politisk en kunstpause og slår ud med armene: »Mere set meget uhomogene iranske diaspora. I behøver man ikke – så har man et show!« 1980erne, skriver professor Halleh Ghorashi Parazit er et godt eksempel på den dialog, og lektor Kees Boersma fra Vrije Universiteit der i dag foregår mellem iranerne i diasporaen Amsterdam, var diasporaen præget af had til og iranerne i Iran. Det satiriske persiskspro- styret i Iran, og venstreorienterede grupper gede tv-show sendes fra Voice of America, og satte dagsordenen. Fra eksilet så man tilbage selvom det iranske makkerpar Kambiz Hos- på Iran, som betragtedes som en »såret fugl« seini og Saman Arbabi kun sender en gang om med et såret folk. -

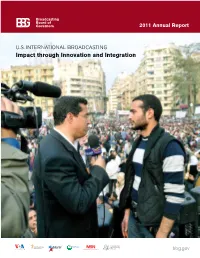

Bbg.Gov BBG Languages Table of Contents

2011 Annual Report U.S. INTERNATIONAL BROADCASTING Impact through Innovation and Integration bbg.gov BBG languages Table of Contents GLOBAL EASTERN/ Letter From the Broadcasting Board of Governors 5 English CENTRAL (including EUROPE Learning Albanian English) Bosnian Croatian AFRICA Greek Afaan Oromoo Macedonian Amharic Montenegrin French Romanian Hausa to Moldova Kinyarwanda Serbian International Kirundi Overview 6 Broadcasting Bureau 16 Ndebele EURASIA Portuguese Armenian Shona Avar Somali Azerbaijani Swahili Bashkir Tigrigna Belarusian Chechen CENTRAL ASIA Circassian Kazakh Crimean Tatar Kyrgyz Georgian Tajik Russian Turkmen Tatar Voice of America 22 Radio Free Europe/ Uzbek Ukrainian Radio Liberty 28 EAST ASIA LATIN AMERICA Burmese Creole Cantonese Spanish Indonesian Khmer NEAR EAST/ Korean NORTH AFRICA Lao Arabic Mandarin Kurdish Thai Turkish Tibetan Radio Free Asia 36 Uyghur Radio and TV Martí 32 SOUTH ASIA Vietnamese Bangla Dari Pashto Persian Urdu Middle East Broadcasting Board On cover: Tarek El-Shamy of Alhurra TV interviews Broadcasting Networks 40 of Governors 44 a protester in Tahrir Square in Cairo. Financial Highlights 47 2 Letter From the Broadcasting Board of Governors 5 [Steve Herman’s tweets]..have kept us ahead of the curve in reporting “aftershocks, tsunami effects and nuclear crisis developments. –Australian Broadcasting Corporation article titled “Journalism’s New Wave, the World in a Tweet” ” VOA correspondent Steve Herman was one of the first American reporters to report from the “depopulated zone” around the crippled Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. 3 Alhurra, Radio Sawa, Afia Darfur and the Voice of America were on hand as the people of South Sudan voted in January 2011 to form a new nation and made their first halting steps toward independence. -

Iran: U.S. Concerns and Policy Responses

Iran: U.S. Concerns and Policy Responses Kenneth Katzman Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs October 26, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL32048 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Iran: U.S. Concerns and Policy Responses Summary The Obama Administration views Iran as a major threat to U.S. national security interests, a perception generated by uncertainty about Iran’s intentions for its nuclear program as well as its materiel assistance to armed groups in Iraq and Afghanistan, to the Palestinian group Hamas, and to Lebanese Hezbollah. Since mid-2011, U.S. officials have openly accused Iran of stepping up support for Iraqi Shiite militias that have attacked U.S. forces, and U.S. officials accused Iran in October 2011 of plotting to assassinate the Saudi Ambassador to the United States. U.S. officials also accuse Iran of helping Syria’s leadership try to defeat a growing popular opposition movement, and of taking advantage of Shiite majority unrest against the Sunni-led, pro-U.S. government of Bahrain. The Obama Administration initially offered Iran’s leaders consistent and sustained engagement with the potential for closer integration with and acceptance by the West in exchange for limits to its nuclear program. After observing a crackdown on peaceful protests in Iran in 2009, and failing to obtain Iran’s agreement to implement any nuclear compromise, the Administration has worked since early 2010 to increase economic and diplomatic pressure on Iran. Significant additional sanctions were imposed on Iran by the U.N. Security Council (Resolution 1929), as well as related “national measures” by the European Union, Japan, South Korea, and other countries. -

BBG) Board from January 2012 Through July 2015

Description of document: Monthly Reports to the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG) Board from January 2012 through July 2015 Requested date: 16-June-2017 Released date: 25-August-2017 Posted date: 02-April-2018 Source of document: BBG FOIA Office Room 3349 330 Independence Ave. SW Washington, D.C. 20237 Fax: (202) 203-4585 The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. Broadcasting 330 Independence Ave.SW T 202.203.4550 Board of Cohen Building, Room 3349 F 202.203.4585 Governors Washington, DC 20237 Office of the General Counsel Freedom of Information and Privacy Act Office August 25, 2017 RE: Request Pursuant to the Freedom of Information Act - FOIA #17-058 This letter is in response to your Freedom of Information Act .(FOIA) request dated June 16, 2017 to the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG), which the Agency received on June 20, 2017. -

SUMMER 2011 the Magazine of University of Maryland University College

SUMMER 2011 SUMMER the magazine of university of maryland university college WWW.UMUC.EDU | 1 | ACHIEVER CONTENTS VIEW FROM THE TOP COVER STORY 10 Dear Friend: 6 THE IRREVERENT VOICE OF IRAN In this issue of Achiever, we look at a changing world—and BY MANDY MCINTYRE those who work to change it. Meet Saman Arbabi—executive producer of a The issue opens with a feature hugely popular show called Parazit and careful on UMUC graduate Saman critic of Iran's oppressive political regime. Arbabi, executive producer of Parazit, a hugely popular Voice of America show that takes a satirical but nonetheless serious look at the oppressive FEATURES regime in Iran—the country Arbabi once called home. The show has been profiled inThe Washington Post and Arbabi has been a guest on 10 MR. FIX-IT The Daily Show with Jon Stewart, but Arbabi has even loftier goals. BY ALLAN ZACKOWITZ Our second feature focuses on Mark Gerencser, chair of UMUC’s Mark Gerencser, chair of UMUC's Board of Visitors, 14 Board of Visitors and executive vice president of consulting giant tackles some of society's most vexing problems— Booz Allen Hamilton. Gerencser likes to fix things—not simple and gets results. This is his story. things like computers, but more complex things like the environment, energy and transportation policy, or national security. The key to 14 THE WAR ON (CYBER) TERROR success as an executive, he says, is “to have the courage to take BY CHIP CASSANO on hard problems.” With support and guidance from industry leaders like ManTech International Corp., UMUC cybersecurity A third feature focuses on UMUC’s still new and growing cybersecurity students are poised to fight cyberterror nationwide. -

Monday 11/16/20 This Material Is Distributed by Ghebi LLC on Behalf

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 11/17/2020 9:27:41 AM Monday 11/16/20 This material is distributed by Ghebi LLC on behalf of Federal State Unitary Enterprise Rossiya Segodnya International Information Agency, and additional information is on file with the Department of Justice, Washington, District of Columbia. Biden Poised to Embrace US Space Force Goals, Expand NASA’s Mission, Experts Claim by Morgan Artvukhina Presumed US President-elect Joe Biden is likely to embrace the new US Space Force rather than seeking to eliminate it because the Democratic Party fundamentally believes defending US space supremacy from Russia and China is a necessary part of US policy. If elected, Biden’s greater focus on fighting climate change could become a boom for NASA, too. Biden has been declared victor in the November 3 US presidential election by much of the US media, and although US President Donald Trump has not accepted the preliminary results and has issued lawsuits challenging the vote count in several state, the presumed president-elect has already begun consolidating a transition team and elaborating on his plans if inaugurated on January 20, 2021. Biden has indicated that he plans to immediately shred many of Trump's policies once he takes office, many of them bv executive order. However, he's said little about what has been one of Trump's biggest projects: the US Space Force (USSF). Experts seem to agree: while Biden isn’t likely to give the USSF the adulation and attention to detail seen from Trump, he isn’t going to discard it, either. -

Journalist Memoirs and the Iranian Di- Aspora: Truth, Professional Ethics, and Objectivity Between Political and Personal Narratives

Journalist Memoirs and the Iranian Di- aspora: Truth, Professional Ethics, and Objectivity between Political and Personal Narratives Babak Elahi and Andrea Hickerson Rochester Institute of Technology Introduction While interviewing Jon Stewart for Voice of America upon the re- lease of Stewart’s adaptation of journalist Maziar Bahari’s Rosewater (2014),1 Iranian-American blogger Saman Arbabi asks, “So, in a sto- ry, like, about Iran, how do you find the truth? I mean who decides what the truth is? And how do you find it?” Stewart admits that he 1Rosewater was originally published in 2011 as Then They Came for Me: A Family’s Story of Love, Captivity, and Survival. Babak Elahi <[email protected]> teaches in the School of Communication at Rochester Insti- tute of Technology. He holds a Ph.D. in American literature from the University ofRochester. His work has been published in Iranian Studies; Alif; MELUS, International Journal of Fash- ion Studies, and Cultural Studies. His book, The Fabric of American Realism, was published by McFarland Press in 2009. Elahi writes about American literary and cultural studies; Iranian culture, film, and literature; and the Iranian diaspora. Andrea Hickerson <[email protected]> is the Director of the School of Communication at Rochester Institute of Technology. She holds a Ph.D. in Communication from the University of Washington. Her work has appeared in Communication Theory, Journalism and Global Networks. She writes about political communication and journalism routines, especially in transnational contexts. 48 Iran Namag, Volume 3, Number 4 (Winter 2019) doesn’t know what the truth is: “Well, I don’t. -

Exporting the First Amendment Strengthening U.S

Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy Discussion Paper Series #D-97, December 2015 Exporting the First Amendment Strengthening U.S. Soft Power through Journalism By David Ensor Joan Shorenstein Fellow, Fall 2015 Former Director of Voice of America Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. Table of Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Soft Power 5 3. BBC World Service 6 4. The Kremlin’s Media 8 5. CCTV: The $7 Billion Network 11 6. Al Jazeera 14 7. The Digital Age 14 8. What Works Best? 16 9. Recommendations to Expand and Improve VOA 22 10. Conclusion 24 11. Endnotes 27 2 “To be persuasive we must be believable; to be believable we must be credible; to be credible we must be truthful.” – Edward R. Murrow Introduction In August 2014, ISIS attacks the town of Shinjar in northern Iraq, sending hundreds of thousands of members of the ancient religious minority known as the Yazidis fleeing up onto Mount Shinjar. Those not already captured are quickly surrounded. Information is scarce, but Voice of America’s Kurdish Service has a Yazidi reporter who soon hears from his people – with what is left of the power in their cell phones. Hundreds of children are dying on the mountain, they tell him. There is no shelter, no food or water. Many have already been executed. Hundreds of young women are being held, raped and used as sex slaves. VOA’s exclusive details are picked up by regional media, alerting U.S. policymakers. “I was talking with one of the ladies, for example,” says Iraqi-born journalist Dakhil Elias. -

PUBLIC DIPLOMACY GANGNAM STYLE a Thesis Submitted to The

PUBLIC DIPLOMACY GANGNAM STYLE A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies By Hida Fouladvand, B.A. Georgetown University Washington, D.C. March 29, 2014 PUBLIC DIPLOMACY GANGNAM STYLE Hida Fouladvand, B.A. MALS Mentor: John H. Brown, Ph.D. ABSTRACT The diplomatic impasse between the United States and Iran is officially broken after thirty-four years of mutual recriminations and mistrust. The need for a reinvigorated U.S. public diplomacy is essential to forge a new relationship based on respect, understanding, and shared political, social, and economic interests. “Gangnam Style” public diplomacy is a simultaneous multiplatform approach to information sharing and engagement that utilizes various programs to stimulate people-to-people connections based on culture, education, and business. By applying this strategy, the current rapprochement between the United States and Iran can be expanded to the benefit of both countries. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A sincere thanks to John H. Brown, a Princeton Ph.D. and former U.S. diplomat who teaches courses on public diplomacy at Georgetown University, for advising me on my thesis. I truly appreciate all the guidance Dr. Brown has given me. My heartfelt gratitude to Ms. Hengameh Fouladvand, a critic and contributor to Encyclopedia Iranica, for her invaluable insights during my research. This thesis is dedicated to a new future for U.S. and Iranian relations. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: 3 GENEVA ICEBREAKER – REOPENING OF U.S. -

76Th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma and Clinical Congress of Acute Care Surgery

76th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma and Clinical Congress of Acute Care Surgery September 13 - September 16, 2017 BALTIMORE MARRIOTT WATERFRONT BALTIMORE, MD HISTORICAL BACKGROUND AAST The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma started with conversations at the meetings of the Western Surgical Association and Southern Surgical Association in December, 1937. The 14 founders, who were present at one or both of these meetings, sub- sequently invited another 68 surgeons to a Founding Members meeting in San Francisco on June 14, 1938. The first meeting of the AAST was held in Hot Springs, Virginia, in May, 1939, and Dr. Kellogg Speed’s first Presidential Address was published in The American Journal of Surgery 47:261-264, 1940. Today, the Association holds an annual scientific meeting, owns and publish- es The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, initiated in 1961, and has over 1,300 members from 30 countries. American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) Annual Meeting of AAST and Clinical Congress of Acute Care Surgery Learning Objectives and Outcomes This activity is designed for surgeons. Upon completion of this program, participants will be able to: • Exchange knowledge pertaining to current research practices and training in the surgery of trauma. • Design research studies to investigate new methods of preventing, correcting, and treating acute care surgery (trauma, surgical critical care and emergency surgery) injuries. CONTINUING MEDICAL EDUCATION CREDIT INFORMATION Accreditation This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and Policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the joint providership of the American College of Surgeons and American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. -

FY 2013 BBG Congressional Budget Request

Broadcasting Board of Governors FY 2013 Budget Request Executive Summary The Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG) supports United States national interests through its mission to inform, engage and connect people around the world in support of freedom and democracy. In accordance with the International Broadcasting Act of 1994 (as amended), the BBG manages and oversees all U.S. civilian international broadcasting, including the Voice of America (VOA), the Office of Cuba Broadcasting (OCB) , and grantee organizations RFE/RL, Inc., Radio Free Asia (RFA), and the Middle East Broadcasting Networks, Inc. (MBN). BBG distributes programming in 59 languages to more than 100 countries via radio, terrestrial and satellite TV, the Internet, mobile devices, and social media. With its global transmission network, the BBG reaches a worldwide weekly audience of 187 million people. U.S. International Broadcasting is among the most cost effective initiatives within public diplomacy. Over 80 percent of BBG language services cost less than $5 million per year to operate, and approximately two-thirds cost less than $2 million per year. The BBG serves as a journalistic catalyst in the support of democracy, civil society, and transparent institutions around the world. All BBG broadcast services adhere to the highest standards of journalistic independence, ethics, and objectivity. We provide an ongoing antidote to censored news. We offer life-saving information during humanitarian emergencies. We develop and direct technologies to penetrate restrictive information firewalls. And when events dictate, the BBG reacts quickly to crises with temporary surges in broadcasting. The BBG’s unique value is to support freedom of press and expression, essential to fostering and sustaining free societies, which directly and tangibly supports U.S. -

2012 Annual Scientific Session

WESTERN SURGICAL ASSOCIATION 2012 Annual Scientific Session Saturday through Tuesday, November 3-6, 2012 The Broadmoor Resort Colorado Springs, Colorado AND Transactions of the 2011 Annual Meeting Loews Ventana Canyon Resort Tucson, Arizona www.westernsurg.org THE BROADMOOR RESORT - COLORADO SPRINGS, CO 1 LOCATION The Broadmoor Resort Colorado Springs, Colorado REGISTRATION Sat, Nov 3 3:00pm - 6:00pm Sun, Nov 4 7:00am - 12 Noon Mon, Nov 5 7:00am - 5:00pm Tue, Nov 6 7:30am - 12 Noon SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS Sun, Nov 4 7:30am - 12 Noon Mon, Nov 5 7:30am - 12 Noon 1:30pm - 4:00pm Tues, Nov 6 8:00am - 12 Noon 2 WSA | 2012 ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSION | NOVEMBER 3–6, 2012 CME MEETING OBJECTIVES 1. Delineate the importance of new diagnostic and therapeutic modalities in surgery. 2. Prioritize treatment of surgical diseases with new operative and non-operative technologies and treatment options. 3. Elucidate the outcome of new surgical procedures. ACCREDITATION STATEMENT This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and Policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education through the joint sponsorship of the American College of Surgeons and the Western Surgical Association. The American College of Surgeons is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians. AMA PRA CATEGORY 1 CREDITS™ The American College of Surgeons designates this live activity for a maximum of 14 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™. *Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity. Of the AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ listed above, a maximum of 13.25 credits meet the requirements for Self-Assessment.