Hospitality – Indian Legal Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Traditional Hotel Industry

CHAPTER 1 The Traditional Hotel Industry Outline Understanding Mom-and-Pop Motels the Hotel Business Class The Service Culture Average Daily Rate A Cyclical Industry Full-Service to Limited-Service How Hotels Count and Measure Number of Employees Occupancy Rating Systems Sales Per Occupied Room Type RevPar (Revenue Per Available Commercial Hotels Room) Residential Hotels Double Occupancy Resort Hotels Break-Even Point Plan Special Characteristics European Plan of the Hotel Business American Plan Perisha bility Variations on the Themes Location Bed and Breakfast (B&B) Fixed Supply Boutique Hotels High Operating Costs Trophy Hotels Seasonality Resources and Challenges Traditional Classifications Resources Size Challenges 3 4 Part I The Hotel Industry Hotels have their origins in the cultures of ancient societies. But the word "hotel" didn't appear until the 18th century. It came from the French hotel, large house, and originated in the Latin roots hospitium or hospes. Hospitality, hostile and hotels are all related words. The difficulty of identifying early travelers as friends or foes probably accounts for the conflict in meanings. Friendly travelers found security and accommodations through the hospitality of their hosts. As the number of travelers increased, personal courtesy gave way to commercial enterprise. The hotel was born carrying with it a culture of hospitality. UNDERSTANDING THE HOTEL BUSINESS The Service Culture The hotel industry grew and flourished through the centuries by adapting to the chang ing social, business and economic environment that marked human progress. During modern times, these stages have been labeled for easy reference. The 18th century was the agricultural age; the 19th, the industrial age. -

Unit- V Room Designations

UNIT- V ROOM DESIGNATIONS Room Designations – Types of Rooms, Room Configurations to suit guest preferences- Numbering of rooms - Room status reconciliation - Room status codes, Discrepancy report. - Glossary of Front Office Terms ROOM DESIGNATIONS The room designation identifies whether it is a smoking or nonsmoking room. In the early 1980’s hotels began to convert a portion of their sleeping rooms to permanently nonsmoking rooms. It is common to find entire floors of hotel sleeping rooms designated as non-smoking. Today, most hotels have a minimum of 50% of their rooms designed as non-smoking. In some markets that figure is as high as 75 to 80 percent. A few hotels have begun to experiment with entirely smoke-free guest rooms. Types of rooms A hotel’s salesman should have a complete knowledge about its products. All those involved in selling of rooms should have the required knowledge about all the rooms in the property. They will then be in a position to recommend & sell the rooms meeting the guest’s requirements. They should know the existing category of rooms, their location & facilities in such rooms. Some of the popular types of rooms found in hotels are as listed below: - 1. Single rooms: - The term refers to a room with a standard single bed to provide sleeping accommodation for one person. The furnishings & fixtures & the amenities of such rooms would be as per the policy of that hotel. The size of a single bed is 6’-3’FT. 2. Double rooms: - The term refers to rooms, which have double beds & provide sleeping comfort for two persons. -

E-Publication-Hospitality-Industry.Pdf

Western India Regional Council of The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India (Set up by an Act of Parliament) E-PUBLICATION ON HOSPITALITY INDUSTRY Create Competence with Ethics Achieve Governance through Innovation © WESTERN INDIA REGIONAL COUNCIL OF THE INSTITUTE OF CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS OF INDIA Published by CA. Lalit Bajaj, Chairman, WIRC, Western India Regional Council of The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India, ICAI Tower, Plot No. C-40, G Block, Opp. MCA Ground, Next to Standard Chartered Bank, Bandra-Kurla Complex, Bandra (East), Mumbai-400 051 Tel.: 022-336 71400 / 336 71500 • E-mail: [email protected] • Web.: www.wirc-icai.org Disclaimer Opinions expressed in this book are those of the Contributors. Western India Regional Council of The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India, does not necessarily concur with the same. While every care is taken to ensure the accuracy of the contents in this compilation, neither contributors nor Western India Regional Council of The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India is liable for any inadvertent errors or any action taken on the basis of this book. ii Western India Regional Council of The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India Foreword Post liberalization, India’s middle class saw substantial growth in income. The growing economy created a culture of travel thus leading to a boom in the country’s hospitality industry which now contributes ~7% to the GDP of India. One of the key drivers of growth in the service sector, the hospitality sector is expected to touch $460 billion by 2028. India has also witnessed considerable growth in foreign visitors since the 2000s, thus enabling our country to become the seventh-largest tourism economy in the world. -

Classification of Hotels

INSTITUTE OF HOTEL MANAGEMENT BHUBANESWAR Est. By Ministry of Tourism, Government of India CLASSIFICATION OF HOTELS A) Classification on the basis of Size. 1) Small hotel : Hotels with 25 rooms or less are classified as small hotels.E.g Hotel Alka,New Delhi and the oberoi Vanyavilas ,Ranthambore. 2) Medium Hotel: Hotel with twenty six to 100 rooms are calledmedium hotels,E.g Hotel Taj view ,Agra and chola sheraton Hotel, Chennai. 3) Large Hotels: Hotels with 101-300 guest rooms are regarded as large hotels E.g. the Imperial, New Delhi, The Park, and Kolkata 4) Very Large Hotels: Hotels more than 300 guest room are known as very large hotels E.g. Shangri-La Hotel, New Delhi and Leela Kempinski Mumbai. B) Classification on the basis of Star. The classification is done by Ministry of Tourism under which a committee forms known as HRACC (Hotels and Restaurants Approval & Classification committee) headed by Director General of tourism comprising of following members are Hotel Industry Travel Agent Association Of India Departments of Tourism Principal of Regional Institute of Hotel Management Catering Technology & Applied Nutrition This is a permanent committee to classify hotels into 1-5 star categories. Generally inspects ones in three years In case of 4 stars, 5 Star, 5 Star deluxe categories, the procedures is to apply on a prescribed application form to director general of tourism. In case of 1, 2, 3 star category to regional director of the concerned govt of India tourist office at Delhi/Mumbai/Kolkata/Chennai. The basic details need to be given: 1) Name of the hotel. -

Hospitality Management and Public Relations

HOSPITALITY MANAGEMENT AND PUBLIC RELATIONS BTS MULTIPLE CHOICE QUESTIONS 1. If you are staying in a five star hotel , you are an a) Extra high budgeted tourist b) Guest of the hotel c) Middle budgeted tourist d) Guest of the company that has invited you 2. A Dharamshala is suitable for a) Those business man who can stay in graded hotels b) Low income families c) Only rich merchants d) All the above 3. What is the main feature of a time share establishment a) It is a private property b) Its rooms / resources are shared by guests / tourists according to specified time schedules. c) It is a facility of one star grade d) None of these 4. In a single bedroom , the number of glasses given to the guests is a) 1 b) 2 c) 4 d) None of these 5. Where is hotel Ashok located in New Delhi a) Jor Bagh b) Chanakya puri c) Sunder Nagar d) New Friends Colony 6. The guest enters into a large hotel from its a) Lobby b) Front Office c) Reception d) Restaurant 7. Cocktails are mixed only by expect cocktail makers or experienced bar tenders. Infact, they are proud of their skills. Why is that so ? a) Cocktails are difficult to make b) It is important to mix different liquors and fruit juices in a correct proportion , the guest should not digest on add cocktail and become sick c) They are at the forefront of the sales departments in the bar and so, they feel proud of their cocktail making skills. -

Serviced Hotel Accommodation

A Guide to the Star Grading Scheme for Serviced Hotel Accommodation Contents Contents Section Details Page 1.0 General Introduction 4 1.1. Introduction 1.1.1 Common Standards Across Britain 4 1.1.2 The Requirements 4 1.1.3 Dispensations 4 1.1.4 How does the assessment system work? 4 1.2 Categories/Designators 6 1.2.1 Hotel Standard Summary & Hotel Designators 6 1.2.2 General Description 6 1.3 Determining the Star Rating 7 1.4 Key Requirements At Each Rating Level 7 1.4.1 One Star – 30-46% 7 1.4.2 Two Star – 47-54% 8 1.4.3 Three Star – 55-69% 8 1.4.4 Four Star – 70-84% 8 1.4.5 Five Star – 85-100% 9 2.0 Detailed Requirements 9 2.1 Overall Standards 9 2.1.1 Statutory Obligations 9 2.1.2 Safety and Security 11 2.1.3 Maintenance 11 2.1.4 Cleanliness 12 2.1.5 Physical Quality 12 2.1.6 Hospitality 12 2.1.7 Services 13 2.1.8 Opening 14 2.1.9 Guest Access 14 2.2 Services 14 2.2.1 Staff appearance 14 2.2.2 Reservations, Prices and Billing 15 2.2.3 Reception: Staff Availability for Guest Arrival and Departure 16 2.2.4 Luggage Handling 17 2.2.5 Other – Reception/Concierge/Housekeeping Services 17 2.3 All Meals – Dining Quality and Information 18 2.3.1 Dining Provision 18 2.3.2 Restaurant Ownership 19 2.3.3 Tables/Table Appointment 19 2.3.4 Meal Service: Staff 20 1 Contents Section Details Page 2.4 Breakfast 20 2.4.1 Provision 20 2.4.2 Breakfast Times 21 2.4.3 Pricing 21 2.4.4 Menu 21 2.4.5 Range of Dishes 22 2.4.6 Food Quality 22 2.4.7 Style of Service 23 2.5 Other Meals 23 2.5.1 Dinner: Hours of Service 23 2.5.2 Range of Dishes 24 2.5.3 Menu and -

A GUIDE to SALES TAX for HOTEL and MOTEL OPERATORS Publication 848 (2/15)

New York State Publication 848 Department of (2/15) Taxation and Finance A GUIDE TO SALES TAX FOR HOTEL AND MOTEL OPERATORS Publication 848 (2/15) About this publication Publication 848 is a guide to New York State and local sales and use taxes administered by the Tax Department as they apply to you in your operation of a hotel, motel or similar establishment. It is intended to provide you, the owner, operator, or manager (collectively to be referred to in this publication as operator or operator of a hotel) with information related to sales tax that is specific to the hotel and motel industry, and to help you understand your sales tax responsibilities. Any reference to sales tax in this publication includes, where appropriate, both the state and local sales and use taxes administered by the Tax Department. Under the Tax Law, a person required to collect tax includes every operator of a hotel and every vendor of taxable tangible personal property or services. Therefore, it is important that you know the taxable status of the rental of rooms, and sales of related tangible personal property and services, including sales of food and drink. This publication provides you with detailed information on the imposition of sales tax on hotel occupancy, the sales tax treatment of the varied transactions that you may be involved in, the permanent resident exclusion, and information on your responsibility when a customer claims an exemption from sales tax. It also includes information on capital improvements to, and the repair and maintenance of hotel/motel premises. -

Accommodation Options Near University of Alberta Hospital/Stollery/MAHI/KEC

Accommodation Options Near: University of Alberta Hospital, Stollery Children’s Hospital, Mazankowski Alberta Heart Institute, Kaye Edmonton Clinic When reserving a room at any facility, be sure to: o Call for rate and room information o Ask for the corporate, hospital, compassionate or medical rate o Be prepared to provide proof of medical condition (i.e. letter from Social Worker or doctor) o Ask about weekly or monthly rates if you expect to be staying for an extended period o Consider requesting non-smoking rooms for medical and overall health reasons Accommodations that offer a medical discount rate have “” by the name. *Costs of rooms are subject to change at any time. Please contact facility for current fees The information presented is not intended to serve as an endorsement for any public or private facility listed: rather it is merely a compilation of options The University of Alberta Hospital, Stollery Children’s Hospital, Mazankowski Alberta Heart Institute, Kaye Edmonton Clinic, and Alberta Health Services, its programs and agents are not responsible to cover any costs incurred by patients, relatives or support persons. These include, but are not exclusive to: damage deposits, housecleaning fees, replacement of property, room service charges, laundry and dry cleaning service Hostels / Dormitories Name Location Cost & Room Information Phone Number UAH Outpatient Corner of 114 Street & Offering Single and Double rooms . No kitchen or cafeteria 780- 407-6593 Residence (OPR) 83 Avenue. Microwave and fridge in common lounge Access from 2nd floor of UAH/SCH Hostelling International 10647-81 Avenue Dormitory Rooms (4-8 bunks in room): 780- 988-6836 (Edmonton) Fees are less for Members; fees also depend on season 1-877-467-8336 Please call to confirm all costs Other Rooms: Private Room Private w/ ensuite Please Note: We do not allow residents of Edmonton or the surrounding area to stay at the hostel Lister Centre Conference Centre Queen and Double rooms, and Hotel-style rooms. -

Classification of Hotels in the Philippines

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF TOURISM MANILA RULES AND REGULATIONS TO GOVERN THE ACCREDITATION OF HOTELS, TOURISTS INNS, MOTELS, APARTELS, RESORTS, PENSION HOUSES AND OTHER ACCOMMODATION ESTABLISHMENTS PURSUANT TO THE PROVISIONS OF EXECUTIVE ORDER NO. 120 IN RELATION TO REPUBLIC ACT NO. 7160, OTHERWISE KNOWN AS THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT CODE OF 1991 ON THE DEVOLUTION OF DOT'S REGULATORY FUNCTION OVER TOURIST ESTABLISHMENTS, THE FOLLOWING RULES AND REGULATIONS TO GOVERN THE ACCREDITATION OF ACCOMMODATION ESTABLISHMENTS ARE HEREBY PROMULGATED. CHAPTER I DEFINITION OF TERMS Section 1. Definition. For purposes of these Rules, the following shall mean: a. Hotel – a building, edifice or premises or a completely independent part thereof, which is used for the regular reception, accommodation or lodging of travelers and tourist and the provision of services incidental thereto for a fee. b. Resort – any place or places with pleasant environment and atmosphere conducive to comfort, healthful relaxation and rest, offering food, sleeping accommodation and recreational facilities to the public for a fee or remuneration. c. Tourist Inn – a lodging establishment catering to transients which does not meet the minimum requirements of an economy hotel. d. Apartel – any building or edifice containing several independent and furnished or semi-furnished apartments, regularly leased to tourists and travelers for dwelling on a more or less long term basis and offering basic services to its tenants, similar to hotels. e. Pension house – a private or family-operated tourist boarding house, tourist guest house or tourist lodging house employing non-professional domestic helpers regularly catering to tourists and travelers, containing several independent lettable rooms, providing common facilities such as toilets, bathrooms/showers, living and dining rooms and/or kitchen and where a combination of board and lodging may be provided. -

Room Service Principles and Practices: an Exploratory Study

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 12-1-2012 Room Service Principles and Practices: An Exploratory Study Stanley Douglas Suboleski University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Food and Beverage Management Commons Repository Citation Suboleski, Stanley Douglas, "Room Service Principles and Practices: An Exploratory Study" (2012). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 1780. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/4332761 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ROOM SERVICE PRINCIPLES AND PRACTICES: AN EXPLORATORY STUDY by Stanley D. Suboleski Bachelors of Science in Theater Syracuse University 1984 Masters of Science in Hotel Administration University of Nevada, Las Vegas 2006 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy in Hospitality Administration William F. Harrah College of Hotel Administration The Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas December 2012 THE GRADUATE COLLEGE We recommend the dissertation prepared under our supervision by Stanley D. -

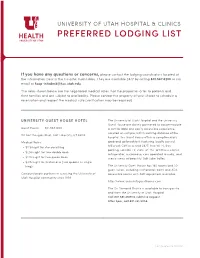

Preferred Lodging List

UNIVERSITY OF UTAH HOSPITAL & CLINICS PREFERRED LODGING LIST If you have any questions or concerns, please contact the lodging coordinators located at the Information Desk in the Hospital main lobby. They are available 24/7 by calling 801.587.8230 or via email at [email protected]. The rates shown below are the negotiated medical rates that the properties offer to patients and their families and are subject to availability. Please contact the property of your choice to schedule a reservation and request the medical rate (verification may be required). UNIVERSITY GUEST HOUSE HOTEL The University of Utah Hospital and the University Guest House are closely partnered to accommodate Guest House: 801.587.1000 a comfortable and easily accessible experience. Located on campus within walking distance of the 110 Fort Douglas Blvd., Salt Lake City, UT 84113 hospital, the Guest House offers a complimentary Medical Rates: grab and go breakfast, featuring locally owned Millcreek Coffee served 24/7, free Wi-Fi, free • $119/night for standard king parking, satellite TV, state-of-the-art fitness center, • $124/night for two double beds refrigerator, microwave, coin operated laundry, and • $129/night for two queen beds scenic views of beautiful Salt Lake Valley. • $215/night for Kitchenette (two queens or single king) The University Guest House has 180 rooms and 30 guest suites, including kitchenette rooms and ADA Compassionate partners in servicing the University of accessible rooms with ASD equipment available. Utah Hospital community since 1999 http://www.universityguesthouse.com The On Demand Shuttle is available to transport to and from the University of Utah Hospital. -

GCC Hospitality Industry | August 23, 2016 Page | 1

GCC Hospitality Industry | August 23, 2016 Page | 1 Alpen Capital was awarded the “Best Research House” at the Banker Middle East Industry Awards 2011, 2013, and 2014 GCC Hospitality Industry | August 23, 2016 Page | 2 Table of Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................... 11 1.1 Scope of the Report ............................................................................................................... 11 1.2 Sector Outlook ....................................................................................................................... 11 1.3 Key Growth Drivers ................................................................................................................ 11 1.4 Key Challenges ...................................................................................................................... 12 1.5 Key Trends ............................................................................................................................ 12 2. THE GCC HOSPITALITY SECTOR OVERVIEW .............................................................. 13 2.1 Tourist Arrivals ....................................................................................................................... 13 2.2 Travel & Tourism (T&T) spending ........................................................................................... 14 2.3 Supply to Keep-up with Demand ...........................................................................................