Complex Events, Propositional Overlay, and the Special Status of Reciprocal Clauses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Does Lateral Transmission Obscure Inheritance in Hunter-Gatherer Languages?

Does Lateral Transmission Obscure Inheritance in Hunter-Gatherer Languages? Claire Bowern1*, Patience Epps2, Russell Gray3, Jane Hill4, Keith Hunley5, Patrick McConvell6, Jason Zentz1 1 Department of Linguistics, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, United States of America, 2 Department of Linguistics, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, United States of America, 3 Department of Psychology, University of Auckland. Auckland, New Zealand, 4 School of Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, United States of America, 5 Department of Anthropology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico, United States of America, 6 College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia Abstract In recent years, linguists have begun to increasingly rely on quantitative phylogenetic approaches to examine language evolution. Some linguists have questioned the suitability of phylogenetic approaches on the grounds that linguistic evolution is largely reticulate due to extensive lateral transmission, or borrowing, among languages. The problem may be particularly pronounced in hunter-gatherer languages, where the conventional wisdom among many linguists is that lexical borrowing rates are so high that tree building approaches cannot provide meaningful insights into evolutionary processes. However, this claim has never been systematically evaluated, in large part because suitable data were unavailable. In addition, little is known about the subsistence, demographic, ecological, and social factors that might mediate variation in rates of borrowing among languages. Here, we evaluate these claims with a large sample of hunter-gatherer languages from three regions around the world. In this study, a list of 204 basic vocabulary items was collected for 122 hunter-gatherer and small-scale cultivator languages from three ecologically diverse case study areas: northern Australia, northwest Amazonia, and California and the Great Basin. -

Nyikina Paradigms and Refunctionalization: a Cautionary Tale in Morphological Reconstruction

Nyikina Paradigms and Refunctionalization: A Cautionary Tale in Morphological Reconstruction Claire Bowern Yale University Department of Linguistics PO Box 208366 New Haven, CT 06520, USA [email protected] Ph: +1.203.432.2045 Keywords: morphology, Nyulnyulan, Australian languages, exaptation, reconstruction, analogy 1 Abstract Here I present a case study of change in the complex verb morphology of the Nyikina language of Northwestern Australia. I describe changes which lead to reanalysis of underlying forms while preserving much of the inherited phonological material. The changes presented here do not fit into previous typologies of morphological change. Nyikina lost the distinction between past and present, and in doing so, merged two paradigms into one. The former past tense marker came to be associated with intransitive verb stems. The inflected verbs thus continue inherited material, but in a different function. These changes are most parsimoniously described in a theory of word formation which makes reference to paradigms. 1 Introduction 1.1 Background Many types of change can occur in morphology. Studies such as Anderson (1988) and Koch (1996) identified a series of processes which cause change in morphemes. These include, in addition to regular sound change which operates on fully inflected forms, various types of boundary shift (such as the absorption of material into stems or the reanalysis of one morpheme as two), and analogical changes such as paradigm regularization. Inflectional material can also be lost. Other processes are particularly associated with morphological change in complex paradigms, though by no means exclusively so. These include so-called “hermit-crab” morphology – and the related change of “lost wax” – described by Heath (1997, 1998). -

Tiwi Revisited: a Reanalysis of Traditional Tiwi Verb Morphology

TIWI REVISITED A reanalysis of Traditional Tiwi verb morphology Aidan Wilson Submitted in total fulfilment of the degree of Master of Arts (Linguistics) December 2013 Department of Linguistics and Applied Linguistics School of Languages and Linguistics Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne For Anita Pangiramini, Justin Puruntatameri, and all people whose languages have gone silent. May they and their words always be remembered. Abstract Traditional Tiwi is a language isolate within the Australian language group, traditionally spoken on the Tiwi Islands, north of Darwin. This language exhibits the most complex verb structure of any Australian language. Altogether there are 18 distinct verb slots; 14 prefixes and 4 suffixes. They encode subject, object and oblique arguments, they inflect for tense, aspect and mood, the location and direction of events with respect to the speaker, and the time of day that an event takes place. They also take prefixes and suffixes denoting associated motion, can be argument-raised by a causative or detransitivised by derivational morphology, and can take incorporated nominals, incorporated verbs, and incorporated comitative or privative arguments. Traditional Tiwi has not been adequately described. Previous descriptions are limited and do not cover verb morphology with enough detail. This thesis brings together previous descriptions, early recorded data, and adds newly collected data and findings to produce an updated description of the language, with special reference to the verb morphology. I focus in particular on two aspects of the verb morphology: agreement and incorporation. The Traditional Tiwi agreement system of inflecting verbs shows a high degree of complexity due to the interactions between subject, object and tense marking. -

Areal Patterns of Grammaticalization and Cross-Linguistic Variation in Grammaticalization Scenarios”

Symposium “Areal patterns of grammaticalization and cross-linguistic variation in grammaticalization scenarios” Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, 12-14 March, 2015 Organizers: Walter Bisang, Andrej Malchukov Abstracts (authors in alphabetical order) Grammaticalization processes in Andean languages Willem F.H. Adelaar (Leiden University) In spite of their rich and complex morphology, the Aymaran and Quechuan languages (spoken in the Central Andes and adjacent areas) are characterized by a lack of transparency in the grammaticalization history of their numerous affixes. For instance, in the Quechuan languages personal reference affixes, both nominal possessive and verbal, lack any significant formal similarity with the corresponding free pronouns. Nevertheless, relatively clear cases of grammaticalization can be found in Quechuan languages as verbal compound tense constructions were transformed into simple tense forms, mainly by deletion or reduction of the auxiliary verb ka- ‗to be‘ and the subsequent attachment of its affixes to an accompanying nominalized verb. Similar processes may have occurred in Aymaran, although the developments underlying them remain obscure. The verb ka- ‗to be‘ probably also played a role in the formation of Quechuan progressive aspect markers (*-yka-, *-ĉka-), although the exact history of these affixes is difficult to determine. Grammaticalization processes that take another grammatical form, rather than a free form, as their point of departure are illustrated by the development of (perfective) aspect markers from derivational markers indicating direction in the Quechuan verb. There is some evidence that connects the directional marker -yku- denoting ‗inward motion‘ to the noun uku ‗inside‘, ‗hollow‘, ‗deep‘. Similarly, *-rqu-, glossed as ‗outward motion‘ and the source of a perfective aspect marker in several modern Quechuan varieties, may eventually be derived from urqu ‗mountain(s)‘, although this assumption remains highly speculative. -

Annual Meeting Handbook

MEETING HANDBOOK LINGUISTIC SOCIETY OF AMERICA AMERICAN DIALECT SOCIETY AMERICAN NAME SOCIETY NORTH AMERICAN ASSOCIATION FOR THE HISTORY OF THE LANGUAGE SCIENCES SOCIETY FOR PIDGIN AND CREOLE LINGUISTICS SOCIETY FOR THE STUDY OF THE INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES OF THE AMERICAS SHERATON BOSTON HOTEL BOSTON, MA 8-11 JANUARY 2004 Introductory Note The LSA Secretariat has prepared this Meeting Handbook to serve as the official program for the 78th Annual Meeting of the Linguistic Society of America (LSA). In addition, this handbook is the official program for the Annual Meetings of the American Dialect Society (ADS), the American Name Society (ANS), the North American Association for the History of the Language Sciences (NAAHoLS), the Society for Pidgin and Creole Linguistics (SPCL), and the Society for the Study of the Indigenous Languages of the Americas (SSILA). We gratefully acknowledge the assistance provided by the LSA Program Committee: (William Idsardi, Chair; Diane Brentari; Peter Culicover; Toshiyuki Ogihara; Margaret Speas; Rosalind Thornton; Lindsay Whaley; and Draga Zec) and the help of the members who served as consultants to the Program Committee. We are also grateful to Marlyse Baptista (SPCL), David Boe (NAAHoLS), Edwin Lawson (ANS), Allan Metcalf (ADS), and Victor Golla (SSILA) for their cooperation. We appreciate the help given by the Boston Local Arrangements Committee chaired by Carol Neidle. We hope this Meeting Handbook is a useful guide for those attending, as well as a permanent record of, the 2004 Annual Meeting in Boston, -

Language and Land in the Northern Kimberley

This item is Chapter 19 of Language, land & song: Studies in honour of Luise Hercus Editors: Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch & Jane Simpson ISBN 978-0-728-60406-3 http://www.elpublishing.org/book/language-land-and-song Language and land in the Northern Kimberley Claire Bowern Cite this item: Claire Bowern (2016). Language and land in the Northern Kimberley. In Language, land & song: Studies in honour of Luise Hercus, edited by Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch & Jane Simpson. London: EL Publishing. pp. 277- 286 Link to this item: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/2019 __________________________________________________ This electronic version first published: March 2017 © 2016 Claire Bowern ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing Open access, peer-reviewed electronic and print journals, multimedia, and monographs on documentation and support of endangered languages, including theory and practice of language documentation, language description, sociolinguistics, language policy, and language revitalisation. For more EL Publishing items, see http://www.elpublishing.org 19 Language and land in the Northern Kimberley Claire Bowern Yale University The coastal Northern Kimberley was home to several Aboriginal groups, as well as being the divide between two major culture areas: the (freshwater) Wanjina groups, and the salt water peoples particularly associated with the names Bardi and Jawi. In this paper I use evidence from place names, cultural ties, language names, mythology, and oral histories to discuss the locations and affiliations of several contested groups in the area. Of particular interest are the Mayala and Oowini groups. In doing this work I build on techniques exemplified and refined by Luise Hercus in her beautiful studies of Central Australian language, land, and culture. -

What's in a Name? a Typological and Phylogenetic

What’s in a Name? A Typological and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Names of Pama-Nyungan Languages Katherine Rosenberg Advisor: Claire Bowern Submitted to the faculty of the Department of Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Yale University May 2018 Abstract The naming strategies used by Pama-Nyungan languages to refer to themselves show remarkably similar properties across the family. Names with similar mean- ings and constructions pop up across the family, even in languages that are not particularly closely related, such as Pitta Pitta and Mathi Mathi, which both feature reduplication, or Guwa and Kalaw Kawaw Ya which are both based on their respective words for ‘west.’ This variation within a closed set and similar- ity among related languages suggests the development of language names might be phylogenetic, as other aspects of historical linguistics have been shown to be; if this were the case, it would be possible to reconstruct the naming strategies used by the various ancestors of the Pama-Nyungan languages that are currently known. This is somewhat surprising, as names wouldn’t necessarily operate or develop in the same way as other aspects of language; this thesis seeks to de- termine whether it is indeed possible to analyze the names of Pama-Nyungan languages phylogenetically. In order to attempt such an analysis, however, it is necessary to have a principled classification system capable of capturing both the similarities and differences among various names. While people have noted some similarities and tendencies in Pama-Nyungan names before (McConvell 2006; Sutton 1979), no one has addressed this comprehensively. -

Skin, Kin and Clan: the Dynamics of Social Categories in Indigenous

Skin, Kin and Clan THE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL CATEGORIES IN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA Skin, Kin and Clan THE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL CATEGORIES IN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA EDITED BY PATRICK MCCONVELL, PIERS KELLY AND SÉBASTIEN LACRAMPE Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN(s): 9781760461638 (print) 9781760461645 (eBook) This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover image Gija Kinship by Shirley Purdie. This edition © 2018 ANU Press Contents List of Figures . vii List of Tables . xi About the Cover . xv Contributors . xvii 1 . Introduction: Revisiting Aboriginal Social Organisation . 1 Patrick McConvell 2 . Evolving Perspectives on Aboriginal Social Organisation: From Mutual Misrecognition to the Kinship Renaissance . 21 Piers Kelly and Patrick McConvell PART I People and Place 3 . Systems in Geography or Geography of Systems? Attempts to Represent Spatial Distributions of Australian Social Organisation . .43 Laurent Dousset 4 . The Sources of Confusion over Social and Territorial Organisation in Western Victoria . .. 85 Raymond Madden 5 . Disputation, Kinship and Land Tenure in Western Arnhem Land . 107 Mark Harvey PART II Social Categories and Their History 6 . Moiety Names in South-Eastern Australia: Distribution and Reconstructed History . 139 Harold Koch, Luise Hercus and Piers Kelly 7 . -

Answer Booklet for William B

Answer booklet for William B. McGregor, 2009 Linguistics: an introduction (London: Continuum) This booklet contains answers to the questions at the end of each chapter of the book. It is intended for use by instructors; please do not distribute it to students. While some problems have relatively clear-cut solutions, others are more or less open-ended. For the former I provide indication of a solution; often there is more than one possible solution, though some are much better than others. If a solution works I always accept it, but rank it against other solutions in terms of complexity and generality. For the open-ended questions I provide some brief remarks on the problem and possible answers, and sometimes remarks on the point of the question. I do not provide model answers, as I presume that lecturers will have their own ideas on what model answers should look like (a model answer to a phonological problem on the website for the book shows what I regard as a model answer). Note that you will probably need to download the font Doulos SIL (see website for the book for a link) in order to read the phonetic symbols correctly. Please send corrections and suggestions for improvements to me at [email protected]. Chapter 1 Issues for further thought and exercises 1. Depicted below are the forms of various signs in everyday use. What are their meanings? Is the sign an icon or a symbol? Justify your answers. ☺☯Ëc] found on road signs in Europe, indicates a tourist site. Most people would probably see this as an arbitrary symbol; however, it is possibly a stylized iconic representation of a castle, in which case one could argue it has some iconic component. -

A Kimberley (Australia) Perspectiver

William McGregor Structural Changes in Language Obsolescence: A Kimberley (Australia) Perspectiver Abstract This paper discusses structural changes in three obsolescent languages from the Kimberley region in the far north-west of Australia, Gooniyandi, Nyulnyul, and Wamva. The changes - which are all comparable with changes attested in language obsolescence situations elsewhere in Australia and the world include a few quite restricted phonological changes, and some more obvious morphological,- syntactic, and lexical changes. These are mainly processes of simplification losses of forms and levelling of systemic distinctions; also discemible is remodelling of- systems bringing them closer to the systems of the dominant language. The range and extent ofchanges differs amongst the tkee languages, correlating with the different synchronic and diachronic conditions of the language obsolescence situations. tThis is a revised version of a paper presented to the SKY symposium Linguistic perspectives on endangered languages,29th August - l't september 2001. I thank the organisers, especially Marja-Liisa Helaswo, for the invitation to talk at the symposium, providing the impetus to retum to a topic that has lain dormant in my mind for over a decade. Thanks a¡e due to the audience for feedback on the presentation, and to two anonymous referees for useful comments on an earlier draft; the usual disclaimers apply. Bronw;m Stokes kindlyprovidedme withher data onNyulnyul and Warnva, while Tsunoda Tasaku generously shared with me the first draft ofhis forthcoming book on language endangerment (Tsunoda inpreparation). My fieldwork on Kimberley languages was funded by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Tones Strait Islander Studies, the Department of Employment, Education and Training (National Aboriginal Languages Program), the Australian Research Council (Large Grants 458930745 and 459332055), the Kimberley Language Resource Centre, and the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics. -

Handbook of Kimberley Languages. Vol. I: General Information

PACIFIC LINGUISTICS Series C - No.I05 HANDBOOK OF KIMBERLEY LANGUAGES Vol ume 1: General Information William McGregor A project of the Kimberley Language Resource Centre Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY McGregor, W. Handbook of Kimberley languages. Vol. I: General information. C-105, xiv + 276 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1988. DOI:10.15144/PL-C105.cover ©1988 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. L PACIFIC LINGUISTICS is issued through the Linguistic Circle of Canberra and consists of fo ur series: SERIES A: Occasional Papers SERIES C: Books SERIES B: Monographs SERIES D: Special Publications FOUNDING EDITOR: SA Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: T.E. Dutton, D.C. Laycock, M.D. Ross, D.T. Tryon EDITORIAL ADVISERS: B.W. Bender H.P. McKaughan University of Hawaii University of Hawaii David Bradley P. Milhlhausler La Trobe University Linacre College, Oxford Michael G. Clyne G.N. O'Grady Monash University University of Victoria, B.C. S.H. Elbert A.K. Pawley University of Hawaii University of Auckland K.J. Franklin K.L. Pike Summer Institute of Linguistics Summer Institute of Linguistics W.W. Glover E.C. Polome Summer Institute of Linguistics University of Texas G.W. Grace Gillian Sank off University of Hawaii University of Pennsylvania M.A.K. Halliday W.A.L. Stokhof University of Sydney University of Leiden E. Haugen B.K. T'sou Harvard University City Polytechnic of Hong Kong A. Healey E.M. -

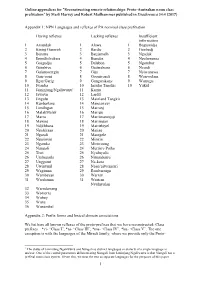

1 Appendix 1

Online appendices for “Reconstructing remote relationships: Proto-Australian noun class prefixation” by Mark Harvey and Robert Mailhammer published in Diachronica 34:4 (2017) Appendix 1: NPN Languages and reflexes of PA nominal class prefixation Having reflexes Lacking reflexes Insufficient information 1 Amurdak 1 Alawa 1 Bugurnidja 2 Bininj Gunwok 2 Bardic 2 Gonbudj 3 Burarra 3 Batjjamalh 3 Ngaduk 4 Enindhilyakwa 4 Bunuba 4 Ngalarrunga 5 Gaagudju 5 Dalabon 5 Ngombur 6 Giimbiyu 6 Gajirrabeng 6 Nyardi 7 Gulumoerrgin 7 Gija 7 Nyiwanawu 8 Gurr-goni 8 Gooniyandi 8 Worrwolam 9 Ilgar/Garig 9 Gungarakany 9 Wurrugu 10 Iwaidja 10 Insular Tangkic 10 Yukul 11 Jaminjung/Ngaliwurru1 11 Kamu 12 Jawoyn 12 Lardil 13 Jingulu 13 Mainland Tangkic 14 Kunbarlang 14 Mangarrayi 15 Limilngan 15 Marranj 16 MalakMalak 16 Marrgu 17 Marra 17 Marrimaninjsji 18 Mawng 18 Marringarr 19 Ndjébbana 19 Marrithiyel 20 Ngalakgan 20 Matige 21 Ngandi 21 Matngele 22 Ngarinyin 22 Minkin 23 Ngarnka 23 Miriwoong 24 Nungali 24 Murriny-Patha 25 Tiwi 25 Nyulnyulic 26 Umbugarla 26 Nimanburru 27 Unggumi 27 Na-kara 28 Uwinymil 28 Ngan’gityemerri 29 Wagiman 29 Rembarrnga 30 Wambayan 30 Warray 31 Wardaman 31 Western Nyulnyulan 32 Warndarrang 33 Worrorra 34 Wubuy 35 Wuna 36 Wunambal Appendix 2: Prefix forms and lexical domain associations We list here all known reflexes of the proto-prefixes that we have reconstructed: Class prefixes – *ci- “Class I”, *ta- “Class III”, *ma- “Class IV”, *ku- “Class V”. The one exception is with the languages of the Mirndi family, where we provide only the Proto- 1 The status of Jaminjung/Ngaliwurru and Nungali as distinct languages or dialects of a single language is unclear.