Institutional Dynamics of Local Self Governance Systems in the Malabar Coast, Kerala1 Baiju K K2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

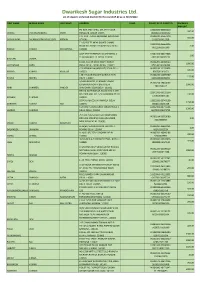

Dwarikesh Sugar Industries Ltd. List of Unpaid / Unclaimed Dividend for the Year 2019-20 As on 31/03/2020

Dwarikesh Sugar Industries Ltd. List of unpaid / unclaimed dividend for the year 2019-20 as on 31/03/2020 FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME LAST NAME ADDRESS FOLIO FOLIO/ DP ID CLIENT ID DIVIDEND AMOUNT PO BOX 3747 SHELL GTL 9TH FLOOR 12032800-00485214- 300.00 CHIRAG PRAVINCHANDRA SHAH MIRQUAB TOWER DOHA 0602321270000152 P.O. BOX - 13027 ABUDHABI ABUDHABI IN300239-14567240- 550.00 GOPAKUMAR PALAMADATHUVASUDEVA MENON OTHERS 10132100012128 T-166 FIST FF NEAR GULATI CHAKKI 12029900-05661905- ROAD NO 20 BALJIT NAGAR New Delhi 2.00 00111000161340 PANKAJ KUMAR SRIVASTAVA 110008 A/67 RESETTLEMENT COLONY KHYALA 12082500-00422908- 1.00 TILAK NAGAR S. O DELHI 110018 603100100005239 BHUVAN VOHRA B-325, SOUTH MOTI BAGH, NANAK IN302269-11080027- 1000.00 CHITRANSHI SAND PURA, DELHI, DELHI, INDIA. 110021 073100100326388 C 20 KIDWAI NAGAR(EAST) DELHI DELHI IN300239-12178458- 500.00 ARVIND KUMAR KHULLAR 110023 9007201006173 J 36 II FLOOR RAJOURI GARDEN NEW IN302236-11096760- 125.00 PAVAN MEHRA DELHI 110027 040104000054269 1/5340 GALI NO 14 BALBIR NAGAR IN300214-19464000- EXTENTION NORTH EAST DELHI 1000.00 7611712117 HARI SHANKER PANDEY SHAHDARA DELHI DELHI 110032 BHOLA NATH NAGAR RAMA BLOCK QTR 12041900-00129504- NO-1900 GALI NO. 5, SHAHADARA DELHI 100.00 13501000005787 NEELAM SHARMA 110032 56 PUNJABI COLONY NARELA DELHI 12033200-05743199- 1250.00 DARSHAN KUMAR HUF 110040 00201110105208 C 29 IIND FLOOR ASHOK VIHAR PHASE 1 12032300-00742101- 1300.00 SHARAD SHARMA DELHI DELHI 110052 0637000104271791 79 C LIG FLATS DDA FLAT MADHUBAN IN300214-20053080- ENCLAVE MADIPUR -

Banco 2016-17 Final

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) CIN/BCIN L51100GJ1961PLC001039 Prefill Company/Bank Name BANCO PRODUCTS (INDIA) LIMITED 22-Sep-2018 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 1930984.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) PUNAMBHAI B PATEL NA NA NA SHRI LAXMI BADAMI COAL FACTORY,INDIA INDUSTRY'S COMPOUND, GUJARAT PRATAPNAGAR, VADODARA. VADODARA 39000400000026 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend1200.00 22-NOV-2024 A NA JAGANNATHANNA NA NA NO-11, BAKTHAWATCHALAM NAGAR,INDIA III STREET, MADRAS CHENNAI TAMIL NADU CHENNAI 60002000010003 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend400.00 22-NOV-2024 ABDUL NA RASHID NA NA NA I/II MAKER TOWERS, CUFFE PARADE,INDIA MUMBAI. MUMBAI MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 40000500010018 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend1000.00 22-NOV-2024 AMRITLAL NA MONGA NA NA NA 31,PRATAP COLONY, MODEL GRAM, INDIALUDHIANA. -

Isolation and Identification of Pathogenic Bacteria in Edible Fish

43672 Megha P U and Harikumar P S / Elixir Bio Sci. 100 (2016) 43672-43677 Available online at www.elixirpublishers.com (Elixir International Journal) Bio Sciences Elixir Bio Sci. 100 (2016) 43672-43677 Isolation and Identification of Pathogenic Bacteria in Edible Fish: A Case Study of Mogral River, Kasargod, Kerala, India Megha P U and Harikumar P S Water Quality Division, Centre for Water Resources Development and Management, Kozhikode, India. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Water is one of the most valued natural resource and hence the management of its quality Received: 26 September 2016; is of special importance. In this study, an attempt was made to compare the aquatic Received in revised form: ecosystem pollution with particular reference to the upstream and downstream quality of 9 November 2016; river water. Water samples were collected from Mogral River and analysed for physico- Accepted: 18 November 2016; chemical and bacteriological parameters. Healthy fish samples from the river basin were subjected to bacteriological studies. The direct bacterial examination of the histological Keywords sections of the fish organ samples were also carried out. Further, the bacterial isolates Mogral River, were taxonomically identified with the aid of MALDI-TOF MS. The physico-chemical Water quality, parameters monitored exceeded the recommended level for surface water quality in the Fish samples, downstream segment. Results of bacteriological analysis revealed high level of faecal Bacterial isolates, pollution of the river. The isolation of enteric bacteria in fish species in the river also MALDI-TOF MS. served as an indication of faecal contamination of the water body. Comparatively, higher bacterial density was found in the liver samples of the fish collected from the downstream, than in other organs of the fish collected from the upstream segment. -

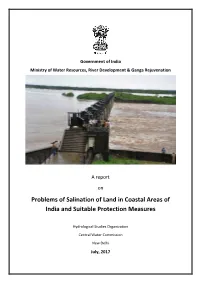

Problems of Salination of Land in Coastal Areas of India and Suitable Protection Measures

Government of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation A report on Problems of Salination of Land in Coastal Areas of India and Suitable Protection Measures Hydrological Studies Organization Central Water Commission New Delhi July, 2017 'qffif ~ "1~~ cg'il'( ~ \jf"(>f 3mft1T Narendra Kumar \jf"(>f -«mur~' ;:rcft fctq;m 3tR 1'j1n WefOT q?II cl<l 3re2iM q;a:m ~0 315 ('G),~ '1cA ~ ~ tf~q, 1{ffit tf'(Chl '( 3TR. cfi. ~. ~ ~-110066 Chairman Government of India Central Water Commission & Ex-Officio Secretary to the Govt. of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation Room No. 315 (S), Sewa Bhawan R. K. Puram, New Delhi-110066 FOREWORD Salinity is a significant challenge and poses risks to sustainable development of Coastal regions of India. If left unmanaged, salinity has serious implications for water quality, biodiversity, agricultural productivity, supply of water for critical human needs and industry and the longevity of infrastructure. The Coastal Salinity has become a persistent problem due to ingress of the sea water inland. This is the most significant environmental and economical challenge and needs immediate attention. The coastal areas are more susceptible as these are pockets of development in the country. Most of the trade happens in the coastal areas which lead to extensive migration in the coastal areas. This led to the depletion of the coastal fresh water resources. Digging more and more deeper wells has led to the ingress of sea water into the fresh water aquifers turning them saline. The rainfall patterns, water resources, geology/hydro-geology vary from region to region along the coastal belt. -

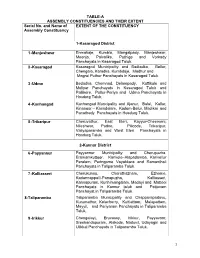

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba -

Indian Red Cross Society, D.K District Branch Life Members Details As on 02.10.2015

Indian Red Cross Society, D.K District Branch Life Members details as on 02.10.2015 Sri. J.R. Lobo, Sri. RTN. P.H.F William M.L.A, D'Souza, Globe Travels, Deputy Commissioner Jency, Near Ramakrishna 1 2 3 G06, Souza Arcade, Balmatta D.K District Tennis Court, 1st cross, Shiva Road, Mangalore-2 Bagh, Kadri, M’lore – 2 Ph: 9845080597 Ph: 9448375245 Sri. RTN. Nithin Shetty, Rtn. Sathish Pai B. Rtn. Ramdas Pai, 301, Diana APTS, S.C.S 4 5 Bharath Carriers, N.G Road 6 Pais Gen Agencies Port Road, Hospital Road, Balmatta, Attavar, Mangalore - 1 Bunder, Mangalore -1 Mangalore - 2 Sri. Vijaya Kumar K, Rtn. Ganesh Nayak, Rtn. S.M Nayak, "Srishti", Kadri Kaibattalu, Nayak & Pai Associates, C-3 Dukes Manor Apts., 7 8 9 D.No. 3-19-1691/14, Ward Ganesh Kripa Building, Matadakani Road, No. 3 (E), Kadri, Mangalore Carstreet, Mangalore 575001 Urva, Mangalore- 575006 9844042837 Rtn. Narasimha Prabhu RTN. Ashwin Nayak Sujir RTN. Padmanabha N. Sujir Vijaya Auto Stores "Varamahalaxmi" 10 "Sri Ganesh", Sturrock Road, 11 12 New Ganesh Mahal, 4-5-496, Karangalpady Cross Falnir, Mangalore - 575001 Alake, Mangalore -3 Road, Mangalore - 03 RTN. Rajendra Shenoy Rtn. Arun Shetty RTN. Rajesh Kini 4-6-615, Shivam Block, Excel Engineers, 21, Minar 13 14 "Annapoorna", Britto Lane, 15 Cellar, Saimahal APTS, Complex New Balmatta Road, Falnir, Mangalore - 575001 Karangalpady, Mangalore - 03 Mangalore - 1 Sri. N.G MOHAN Ravindranath K RTN. P.L Upadhya C/o. Beta Agencies & Project 803, Hat Hill Palms, Behind "Sithara", Behind K.M.C Private Ltd., 15-12-676, Mel Indian Airlines, Hat Hill Bejai, 16 17 18 Hospital, Attavar, Nivas Compound, Kadri, Mangalore – 575004 Mangalore - 575001 Mangalore – 02. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kasaragod District from 06.06.2021To12.06.2021

Accused Persons arrested in Kasaragod district from 06.06.2021to12.06.2021 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 220/2021 U/s 15 of KG Act POOKUMBEL & 4(2)(j)of Bhaskaran M Paadi HOUSE 12-06-2021 KEDO RAJAPURA ,SI OF MATHACH 49, ,mannadukka BAILED BY 1 SHIBU P M CHERUPANATHA at 15:40 &3(a),3(b) of M POLICE AN Male m,panathadi POLICE DI PANATHADI Hrs KEDCVD (Kasaragod) ,RAJAPURA village VILLAGE Additional M P S Regulations 2020 220/2021 U/s 15 of KG Act KUNCHARAKKAT & 4(2)(j)of Paadi TU HOUSE CHERU 12-06-2021 KEDO RAJAPURA BASKARAN 44, ,mannadukka BAILED BY 2 BINOY P J MATHAI PANATHADI at 15:40 &3(a),3(b) of M M ,SI OF Male m ,panathadi POLICE PANATHADI Hrs KEDCVD (Kasaragod) POLICE village VILLAGE Additional Regulations 2020 236/2021 U/s 15(c) r/w 63 of Abkari Act KAINTHAR and 4(2)(a)(j) MURALI KV , HOUSE 11-06-2021 MELPARA IN SHANMUG KUNHIRAM 40, PARAVANA r/w 4(iv) of SUB 3 KAINTHAR at 16:35 MBA JUDICIAL AN.K.T AN Male DUKKAM Kerala INSPECTOR CHEMMANAD Hrs (Kasaragod) CUSTODY - Epidemic OF POLICE VILLAGE Diseases Ordinance 2020 Bhaskaran M Maliyekkal (H) 12-06-2021 219/2021 U/s RAJAPURA IN Anoop 40, ,SI of 4 Scaria Udayapuram Rajapuram PS at 12:45 452,341,324,30 M JUDICIAL Scariya Male Police,Rajapur Kodom Hrs 8,506,427 IPC (Kasaragod) CUSTODY - am PS Pallikkal House, Palakunnu, 11-06-2021 346/2021 -

Kalamkanippu Mahotsavam Palakunnu Sree Bhagavathi Temple

KALAMKANIPPU MAHOTSAVAM PALAKUNNU SREE BHAGAVATHI TEMPLE Panchayat/ Municipality/ Bedadka Panchayat Corporation LOCATION District Kasaragode Nearest Town/ BadarBadar Masjid Masjid Kalnad Kalnad Bus Bus Stand Stand – – 3.1 3.1 km Km Landmark/ Junction Nearest Bus Station Badar Masjid Kalnad Bus Stand – 3.1 Km Nearest Railway Kottikulam Railway Station – 160 m Station ACCESSIBILITY Nearest Airport Mangalore International Airport – 69.8 Km Palakkunnu Shree Bhagavathi Temple Palakkunnu P.O Bekal-671318 Phone: +91-4672-236340 CONTACT Website: www.palakkunnutemple.com DATES FREQUENCY DURATION TIME December – January, January - February Twice a year 3 Days ABOUT THE FESTIVAL (Legend/History/Myth) Palakkunnu Sree Bhagavathi Temple, the most famous Temple of Northern Kerala, is a well known cultural and spiritual center of the region, situates in Kasaragod District. The Temple is situated just 50 meters away from the Kottikulam Railway Station and 3 km away from the Bekal Fort, the international tourist centre. Bhagavathy or mother goddess is the main deity. Bhagavathi is worshipped in two forms as Mootha Bhagavathi (Durga) and Elaya Bhagavathi (Saraswathi). Besides these two Goddesses, Vishnumoorthi, Ghantakarnan and Dhandan Devan are the other deities. The festivals of the Temple are being celebrated by the active participation of the entire society. There is no bar on people from any caste or race from visiting the Temple. The Temple is famous for some of the rarest traditional customary rituals and ceremonies. Local Approximately 5000 RELEVANCE- NO. OF PEOPLE (Local / National / International) PARTICIPATED EVENTS/PROGRAMS DESCRIPTION (How festival is celebrated) Tantric Rituals Kalamkanippu Mahotsavam, a rare celebration in the Grant procession with pots region has much similarity with the Pongala of Attukal Cultural programs Temple, Thiruvananthapuram. -

Proposed Date of Transfer to IEPF (DD-MON

Investor Name Address Country State Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type Amount (Rs.) Proposed Date of transfer to IEPF (DD-MON-YYYY) A K SINGH 1-11-252, ST NO.3 216, ALADDIN MANSION NEXT TO SHOPPERS INDIA Andhra Pradesh 500001 HAWK000000000A001686 Amount for unclaimed 5160.00 03-Oct-2018 STOP BEGUMPET, HYDERABAD and unpaid dividend A KRISHNA MOHANRAO 35/A, VENGAL RAO NAGAR HYDERABAD INDIA Andhra Pradesh 500038 HAWK000000000A001566 Amount for unclaimed 600.00 03-Oct-2018 and unpaid dividend A M SINGHVI NO-6 11TH CROSS STREET SASTRI NAGAR ADYAR MADRAS INDIA Tamil Nadu 600020 HAWK000000000A000014 Amount for unclaimed 5600.00 03-Oct-2018 and unpaid dividend A R KRISHNAPRASAD C/O. RAJAGOPAL STORES , 103, 11TH CROSS, VYALIKAVAL, INDIA Karnataka 560003 HAWK000000000A001646 Amount for unclaimed 680.00 03-Oct-2018 MALLESWARAM, BANGALORE and unpaid dividend ABHAY M PETHE 17 VYANKATESH PRASAD N C KELKAR ROAD DADAR BOMBAY INDIA Maharashtra 400028 HAWK000000000A000039 Amount for unclaimed 1120.00 03-Oct-2018 and unpaid dividend ABHIJEET MONDAL SH 5A 90, DRDO TOWNSHIP PHASE 2, C V RAMAN NAGAR, INDIA Karnataka 560093 IN302269-10476283-0000 Amount for unclaimed 2760.00 03-Oct-2018 BANGALROE KARNATAKA and unpaid dividend AJAY J KANAKIA 13 BHAGWATI BHUWAN 31/B CARMICHAEL ROAD NEXT TO INDIA Maharashtra 400026 HAWK000000000A001879 Amount for unclaimed 200.00 03-Oct-2018 RUSSIAN CULTURAL CENTRE PEDDAR ROAD and unpaid dividend AJAY LAL S/O LATE PREM PRAKASH LAL E-30A, BRIJ VIHAR INDIA Uttar Pradesh 201011 HAWK000000000A001670 Amount for unclaimed 3520.00 03-Oct-2018 GHAZIABAD,T.H.A UP and unpaid dividend AJIT RAMANLAL SHAH C/O SEALS PRODUCTS 6 GAURAV INDL. -

Name of District : KASARAGOD Phone Numbers LAC NO

Name of District : KASARAGOD Phone Numbers LAC NO. & PS Name of BLO in Name of Polling Station Designation Office address Contact Address Name No. charge office Residence Mobile "Abhayam", Kollampara P.O., Nileshwar (VIA), K.Venugopalan L.D.C Manjeshwar Block Panchayath 04998272673 9446652751 1 Manjeswar 1 Govt. Higher Secondary School Kunjathur (Northern Kasaragod District "Abhayam", Kollampara P.O., Nileshwar (VIA), K.Venugopalan L.D.C Manjeshwar Block Panchayath 04998272673 9446652752 1 Manjeswar 2 Govt. Higher Secondary School Kunjathur (Northern Kasaragod District N Ishwara A.V.A. Village Office Kunjathur 1 Manjeswar 3 Govt. Lower Primary School Kanwatheerthapadvu, Kun M.Subair L.D.C. Manjeshwar Block Panchayath Melethil House, Kodakkad P.O. 04998272673 9037738349 1 Manjeswar 4 Govt. Lower Primary School, Kunjathur (Northern S M.Subair L.D.C. Manjeshwar Block Panchayath Melethil House, Kodakkad P.O. 04998272673 9037738349 1 Manjeswar 5 Govt. Lower Primary School, Kunjathur (Southern Re Survey Superintendent Office Radhakrishnan B L.D.C. Ram Kunja, Near S.G.T. High School, Manjeshwar 9895045246 1 Manjeswar 6 Udyavara Bhagavathi A L P School Kanwatheertha Manjeshwar Arummal House, Trichambaram, Taliparamba P.O., Rajeevan K.C., U.D.C. Manjeshwar Grama Panchayath 04998272238 9605997928 1 Manjeswar 7 Govt. Muslim Lower Primary School Udyavarathotta Kannur Prashanth K U.D.C. Manjeshwar Grama Panchayath Udinur P.O., Udinur 04998272238 9495671349 1 Manjeswar 8 Govt. Upper Primary School Udyavaragudde (Eastern Prashanth K U.D.C. Manjeshwar Grama Panchayath Udinur P.O., Udinur 04998272238 9495671349 1 Manjeswar 9 Govt. Upper Primary School Udyavaragudde (Western Premkumar M L.D.C. Manjeshwar Block Panchayath Meethalveedu, P.O.Keekan, Via Pallikere 04998 272673 995615536 1 Manjeswar 10 Govt. -

Details of Affected People During the Flood 2018

Details of affected people during the Flood 2018 Amout_P Amount_ Amount_ Damag aid_Install Paid_Inst Paid_Inst e(Full/p Appication_no Taluk_name Village_name Localbody_name Applicant_Name Address ment_Firs allment_S allment_T artial) t ocond hird Full 13936/18 Kasaragod Kumbadaje kumbadajeGp SADHU PADMAR 95100 152450 152450 Full 19522/18 Kasaragod badiyadka Badiadka GP Gopalakrishna yenakudlu 95100 152450 152450 Full 15804/18 Kasaragod Pady Chengala GP susheela tholarmb 95100 Full 20992/18 Kasaragod muliyar Muliyar GP Baby kallukandam 95100 152450 Full 14239/18 Kasaragod ADOOR Delampady GP MUHAMMEDCA pandi house 95100 152450 152450 Full 14956/18 Kasaragod Delampady Delampady GP parvathi delampady 95100 152450 152450 Full 16251/18 Kasaragod Bandadka kuttikol gp Ragavan vr mavilankatta 95100 152450 152450 Full 12661/18``` Kasaragod kolathur Bedadka Gp nalini ekkal house 95100 152450 Full 23812/18 Kasaragod munnad Bedadka Gp narayani h chechakkayam 95100 152450 152450 Full 19643/18 Kasaragod munnad Bedadka Gp ragavan nair anadamadam 95100 Adukathil Full Vellarikundu Kinanur Kinnanur Karindhalam Sreedharan A 101900 veedu,Periyanganam Full Vellarikundu Kinanur Kinnanur Karindhalam V.K Lekshmi Vottaradi,Kollampara 101900 Full Vellarikundu Maloth West Eleri Rosamma Tomi Kunnathan, Maloth 101900 149050 Full Vellarikundu Maloth West Eleri Jesy @ Mariyama Kannervadi, Maloth 101900 149050 Mvungall(H),Ayyakunn Full Vellarikundu Thaynnur Kodombelur Janaki K 101900 u Thaivalapil,Kallichanad Full Vellarikundu Thaynnur Kodombelur Baskaran P 101900 ukkam -

Village Name Age M/F Address Mob No Hosdurg Taluk Village- Kayyur

Shifted to relatives Hosdurg Taluk Village- Kayyur Sl Camp Head of No Village Name Name Age M/F Address Mob No Family 1 Kayyur Shifted Karthyayani P V 70 Female Kookkottu FH 2 Kayyur Shifted Deepa M F Kayyur FH 3 Kayyur Shifted Thambayi K 68 F Kayyu 9400463878 FH Karunakaran TV Kunhipurakkal 4 Kayyur Shifted Veedu Kayyu FH 5 Kayyur Shifted Narayani N V Kayyur 6 Kayyur Shifted Ambu M 84 M Kayyu FH 7 Kayyur Shifted Shyma K F Kayyu FH 8 Kayyur Shifted Chandramathi B P Kayyu FH 9 Kayyur Shifted Devaki T P 55 F Kayyur 9747359379 FH Chalakkava 10 Kayyur Shifted C V Gangadharan 57 M lappil 9946355095 FH Narayani K 11 Kayyur Shifted Puthirankai 59 F Kayyur 8943066182 FH 12 Kayyur Shifted Kumaran K 66 M Kayyu 8547907470 FH Puthiramka 13 Kayyur Shifted Padmini P 62 F i veedu 9847404005 FH Chalakkava 14 Kayyur Shifted Kamalakshi K 58 F lappil 9061507678 FH Puthiramka 15 Kayyur Shifted Rohini P K 61 F i veedu 8547388387 FH Page 1 Shifted to relatives Kunhithaiv alappil,Kay 16 Kayyur Shifted Aneesh P 35 M yur 9495417010 FH 17 Kayyur Shifted Biju M 43 M 9961658748 FH 18 Kayyur Shifted Omana 43 F Kayyur 9447464882 FH 19 Kayyur Shifted Madhavi K V 65 F Kayyu 9656448352 FH Kandathil 20 Kayyur Shifted K P Narayani 79 F purayil 9961553107 FH Puthiramka 21 Kayyur Shifted Shyja A 37 F i veedu 9497138152 FH 22 Kayyur Shifted Dineshan P K M Kayyur 9497138152 23 Kayyur Shifted Indira P 43 F Kayyu 8086461972 FH 24 Kayyur Shifted Karthyayani C V 49 F Kayyu 8330052429 FH 25 Kayyur Shifted Narayani C 55 F Kayyu 9496628972 FH Cheralath 26 Kayyur Shifted Yasoda C