74 Diliman Gender Review 2018 75

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Index of Session Participants

INDEX OF SESSION PARTICIPANTS A Aguilera, Isabel (421) Alonso, Paul T. (1079) Aguiló, Ignacio A. (403) Alonso, Paula (200, 241, 745, 1092) Abal Medina, Juan Manuel M. (099) Aguirre Darancou, Iván E. (227) Alonso-Regalado, Jesús (011) Abanto, Luis A. (133) Aguirre, Gabriela (1144) Alpert-Abrams, Hannah (068, 679) Abbott, Jared A. (511) Aguirre, Laura (936) Alpízar Lobo, Natasha (646) Abdalla, María de Fátima Barbosa (256) Ajmechet, Sabrina (339, 1109) Altamiranda, Liney Patricia (384) Abraham, Jenaro A. (260) Akchurin, Maria (481) Altamirano, Faustino A. (638) Abramo, Pedro (121, 461) Alabarces, Pablo A. (545) Altamirano, Isabel (809, 1099) Abramovay, Miriam (050) Alamo, Hector Luis (697) Altmann, Philipp (1098, 1188) Abrantes Martins, Pedro (1021) Alarcon Menchaca, Laura (435) Aluma-Cazorla, Andrés (1012) Abrego, Leisy J. (300, 860, 1065) Alarcon, Daniela F. (466) Alvarado Mendoza, Arturo (399) Abreu, Alberto (956) Alarcón, Rafael G. (431) Alvarado Salgado, Sara V. (210) Abreu, Luciano A. (997) Alba Vega, Carlos José (702, 969) Alvarado Valladares, Kristhel (614) Abreu, Mariana (701) Alba Villalever, Ximena (937) Alvarado, Leticia (687) Aca Garcia, Alondra C. (1138) Albarracin Dierolf, Juan G. (185, 1153) Alvarado, María Eugenia (789) Acácio, Igor (684) Alberti, Carla (726) Alvarado, Paulo (036) Acciari, Louisa (769, 822) Albertini Daenekas Rubim, Stephanie Álvarez Acosta, María Elena (729) Accioly, Maria Izabel F. (552) (1097) Alvarez Hernandez, Analays (289) Acevedo Carvajal, Juan Manuel (1159) Alberto, Paulina L. (042, 500, 792) Alvarez Hernández, Graciela Carolina Acevedo, Jorge (063, 1004) Albo Díaz, Ana N. (968) (700) Acevedo, Juan F. (617, 1127) Alburquenque, Gabriela A. (448) Alvarez Ibarra, Cesar Ivan (878) Acevedo-Guerrero, Tatiana (829) Alcañiz, Isabella (1063) Alvarez Nazareno, Carlos (792) Aceves Sepúlveda, Gabriela (551) Alcántar, Iliana (528) Álvarez Ramírez, Sandra (096) Achondo, Luis (964) Alcaraz, Maria Florencia (536) Alvarez Sifonte, Pedro (302) Achugar, Mariana (130) Aldama, Dulce (843) Álvarez Velasco, Carla Morena M. -

Dr. Riz A. Oades Passes Away at Age 74 by Simeon G

In Perspective Light and Shadows Entertainment Emerging out Through the Eye Sarah wouldn’t of Chaos of the Needle do a Taylor Swift October 9 - 15, 2009 Dr. Riz A. Oades passes away at age 74 By Simeon G. Silverio, Jr. Publisher & Editor PHILIPPINES TODAY Asian Journal San Diego The original and fi rst Asian Philippine Scene Journal in America Manila, Philippines | Oct. 9, It was a beautiful 2008 - My good friend and compadre, Riz Oades, had passed away at age 74. He was a “legend” of San Diego’s Filipino American Community, as well day after all as a much-admired academician, trailblazer, community treasure and much more. Whatever super- Manny stood up. His heart latives one might want to apply was not hurting anymore. to him, I must agree. For that’s Outside, the rain had how much I admire his contribu- stopped, making way for tions to his beloved San Diego Filipino Americans. In fact, a nice cool breeze of air. when people were raising funds It had been a beautiful for the Filipinos in the Philip- day after all, an enchanted pines, Riz was always quick to evening for him. remind them: “Don’t forget the Bohol Sunset. Photo by Ferdinand Edralin Filipino Americans, They too need help!” By Simeon G. I am in Manila with my wife Silverio, Jr. conducting business and visit- Loren could be Publisher and Editor ing friends and relatives. I woke up at 2 a.m. and could not sleep. Asian Journal When I checked my e-mail, I San Diego read a message about Riz’s pass- temporary prexy The original and fi rst ing. -

![J. Leonen, En Banc]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0526/j-leonen-en-banc-300526.webp)

J. Leonen, En Banc]

EN BANC G.R. No. 221697 - MARY GRACE NATIVIDAD S. POE LLAMANZARES, Petitioner, v. COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS and ESTRELLA C. ELAMPARO, Respondents. G.R. No. 221698-700 - MARY GRACE NATIVIDAD S. POE LLAMANZARES, Petitioner, vs. COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS, FRANCISCO S. TATAD, ANTONIO P. CONTRERAS, and AMADO T. VALDEZ, Respondents. Promulgated: March 8, 2016 x---------------------------------------------------------------------~~o=;::.-~ CONCURRING OPINION LEONEN, J.: I am honored to concur with the ponencia of my esteemed colleague, Associate Justice Jose Portugal Perez. I submit this Opinion to further clarify my position. Prefatory The rule of law we swore to uphold is nothing but the rule ofjust law. The rule of law does not require insistence in elaborate, strained, irrational, and irrelevant technical interpretation when there can be a clear and rational interpretation that is more just and humane while equally bound by the limits of legal text. The Constitution, as fundamental law, defines the mm1mum qualifications for a person to present his or her candidacy to run for President. It is this same fundamental law which prescribes that it is the People, in their sovereign capacity as electorate, to determine who among the candidates is best qualified for that position. In the guise of judicial review, this court is not empowered to constrict the electorate's choice by sustaining the Commission on Elections' actions that show that it failed to disregard doctrinal interpretation of its powers under Section 78 of the Omnibus Election Code, created novel jurisprudence in relation to the citizenship of foundlings, misinterpreted and misapplied existing jurisprudence relating to the requirement of residency for election purposes, and declined to appreciate the evidence presented by petitioner as a whole and instead insisted only on three factual grounds j Concurring Opinion 2 G.R. -

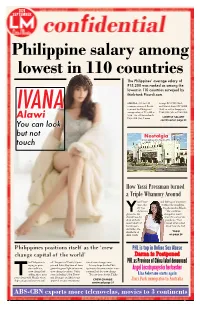

1 Angel Locsin Prays for Her Basher You Can Look but Not Touch How

2020 SEPTEMBER Philippine salary among lowest in 110 countries The Philippines’ average salary of P15,200 was ranked as among the Do every act of your life as if it were your last. lowest in 110 countries surveyed by Marcus Aurelius think-tank Picordi.com. MANILA - Of the 110 bourg’s P198,500 (2nd), countries reviewed, Picodi. and United States’ P174,000 com said the Philippines’ (3rd), as well as Singapore’s IVANA average salary of P15,200 is P168,900 (5th) at P168,900, 95th – far-off Switzerland’s Alawi P296,200 (1st), Luxem- LOWEST SALARY continued on page 24 You can look but not Nostalgia Manila Metropolitan Theatre 1931 touch How Yassi Pressman turned a Triple Whammy Around assi Press- and feelings of uncertain- man , the ty when the lockdown 25-year- was declared in March. Yold actress “The world has glowed as she changed so much shared how she since the start of the dealt with the pandemic,” Yassi recent death of mused when asked her 90-year- about how she had old father, the YASSI shutdown of on page 26 ABS-CBN Philippines positions itself as the ‘crew PHL is top in Online Sex Abuse change capital of the world’ Darna is Postponed he Philippines is off. The ports of Panila, Capin- tional crew changes soon. PHL as Province of China label denounced trying to posi- pin and Subic Bay have all been It is my hope for the Phil- tion itself as a given the green light to become ippines to become a major inter- Angel Locsin prays for her basher crew change hub, crew change locations. -

PH Agency Fined $112K for Illegal Placement

Page 28 Page 10 Page 19 ITALY. Zsa Zsa Padilla VIEWS. The Philippine plans to tie the knot Consulate General next year with her is showing to the boyfriend Conrad public a controversial Onglao in the land of documentary on the Romeo and Juliet. South China Sea. SUCCESS. This Cebuano graduated from the Chinese University of Hong Kong at the top of The No.1 Filipino Newspaper Vol.VI No.328 August 1, 2015 his class. PH agency US hits abuse fined $112k for illegal placement of FDHs in HK fee By Philip C. Tubeza PHILIPPINE Overseas Employment Administration (POEA) chief Hans Cacdac Jr. cancelled the license of a recruitment agency in Manila and or- dered it to pay P650,000 for collecting an illegal placement fee from a Filipina domestic worker in Hong Kong. In an order on June 25, Cacdac also banned the officers and directors of Kan-ya International Services Corp. from recruiting overseas Filipino work- ers (OFWs) for collecting a placement fee of P85,000 from complainant Sarah V. Nievera. The POEA pursued the case even after Nievera issued an affidavit of de- sistance. “As a consequence of the penalty of cancellation of license, the officers and directors of the respondent agency at the time of the commission of the of- fense are hereby disqualified from par- ticipating in the business of recruitment and placement of (OFWs),” Cacdac said. He also ordered Kan-ya and its in- surance firm to refund the amount of P85,000 that was collected from Nie- vera. In her complaint, Nievera said she ap- THE FINALE. -

Brillante Mendoza

Didier Costet presents A film by Brillante Mendoza SYNOPSIS Today Peping will happily marry the young mother of their newborn baby. For a poor police academy student, there is no question of turning down an opportunity to make money. Already accustomed to side profits from a smalltime drug ring, Peping naively accepts a well-paid job offer from a corrupt friend. Peping soon falls into an intense voyage into darkness as he experiences the kidnapping and torture of a beautiful prostitute. Horrified and helpless during the nightmarish all-night operation directed by a psychotic killer, Peping is forced to search within if he is a killer himself... CAST and HUBAD NA PANGARAP (1988). His other noteworthy films were ALIWAN PARADISE (1982), BAYANI (1992) and SAKAY (1993). He played in two COCO MARTIN (Peping) Brillante Mendoza films: SERBIS and KINATAY. Coco Martin is often referred to as the prince of indie movies in the Philippines for his numerous roles in MARIA ISABEL LOPEZ (Madonna) critically acclaimed independent films. KINATAY is Martin's fifth film with Brillante Mendoza after SERBIS Maria Isabel Lopez is a Fine Arts graduate from the (2008), TIRADOR/SLINGSHOT (2007), KALELDO/SUMMER University of the Philippines. She started her career as HEAT (2006) and MASAHISTA/ THE MASSEUR (2005). a fashion model. In 1982, she was crowned Binibining Martin's other film credits include Raya Martin's NEXT Pilipinas-Universe and she represented the Philippines ATTRACTION, Francis Xavier Pasion's JAY and Adolfo in the Miss Universe pageant in Lima, Peru. After her Alix Jr.'s DAYBREAK and TAMBOLISTA. -

Advisory No. 002, S. 2020 January 03, 2020 in Compliance with Deped Order (DO) No

Advisory No. 002, s. 2020 January 03, 2020 In compliance with DepEd Order (DO) No. 8, s. 2013 this advisory is issued not for endorsement per DO 28, s. 2001, but only for the information of DepEd officials, personnel/staff, and the concerned public. (Visit www.deped.gov.ph) WINNERS OF THE 2019 METRO MANILA FILM FESTIVAL The 2019 Metro Manila Film Festival (MMFF) Gabi ng Parangal was held on December 27, 2019 at the New Frontier Theater in Araneta Center, Cubao, Quezon City. Mindanao a 2019 drama film produced under Center Stage Productions, and directed by Brillante Mendoza, won the top awards garnering the Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor for Allen Dizon, Best Actress for Judy Ann Santos, and Best Child Performer for Yuna Tangog . Judy Ann Santos played as Saima Datupalo, who cares for her cancer-stricken daughter Aisa (Yuna Tangog) while she awaits home for her husband Malang (Allen Dizon), a combat medic deployed to fight rebel forces in the southern Philppines. Their struggle is juxtaposed with the folklore of Rajah Indara Patra and Rajah Sulayman, the sons of Sultan Nabi, who fights to stop a dragon devastating Lanao. Mindanao also won six special MMFF award including FPJ Memorial Award for Excellence, Gatpuno Antonio J. Villegas Cultural Award, Best Visual Effects, Best Sound, Gender Sensitivity and Best Float Awards. The historical drama film Culion won the Special Jury Prize Award. Culion is directed by Alvin Yapan, starring Iza Calzado (Ana), Jasmine Curtis-Smith (Doris), and Meryll Soriano (Ditas). Set in the 1940s, the movie tells the story of three women seeking a cure for leprosy. -

![THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7828/the-humble-beginnings-of-the-inquirer-lifestyle-series-fitness-fashion-with-samsung-july-9-2014-fashion-show-667828.webp)

THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]

1 The Humble Beginnings of “Inquirer Lifestyle Series: Fitness and Fashion with Samsung Show” Contents Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ................................................................ 8 Vice-Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................... 9 Popes .................................................................................................................................. 9 Board Members .............................................................................................................. 15 Inquirer Fitness and Fashion Board ........................................................................... 15 July 1, 2013 - present ............................................................................................... 15 Philippine Daily Inquirer Executives .......................................................................... 16 Fitness.Fashion Show Project Directors ..................................................................... 16 Metro Manila Council................................................................................................. 16 June 30, 2010 to June 30, 2016 .............................................................................. 16 June 30, 2013 to present ........................................................................................ 17 Days to Remember (January 1, AD 1 to June 30, 2013) ........................................... 17 The Philippines under Spain ...................................................................................... -

At Last, Filipino Cinema in Portugal July 10, 2013/ Tiago Gutierrez Marques

At Last, Filipino Cinema in Portugal July 10, 2013/ Tiago Gutierrez Marques A scene from Brillante Mendoza's "Captive" (Source: filmfilia.com) I didn't know anything about Filipino cinema until very recently, as it’s practically unheard of in Portugal where most people don't even know where the Philippines is on the world map. But there are signs of change. In 2010 a Portuguese cultural association called “Zero em Comportamento” (Zero Behavior), which is dedicated to the dissemination of movies that fall outside the mainstream commercial cinema, organized a four-day retrospective showing in Lisbon of movies directed by acclaimed Filipino director Brillante Mendoza. This also included a masterclass on independent filmmaking in the Philippines, for cinema students and professionals (http://zeroemcomportamento.wordpress.com/arquivo/bmendoza/). This rare opportunity got me very excited, and particularly my Portuguese father, who went to see almost all of the eight movies. At the end of each showing, the audience could directly ask Brillante Mendoza their questions. And just a few months ago, one of Mendoza's latest films, “Captive,” was released in commercial theaters in Lisbon and Porto (Portugal's second city) alongside the usual Hollywood blockbusters. I couldn't believe that we had reached a new milestone for Filipino cinema in Portugal. Director Brillante Mendoza won the Palme d'Or at the 2009 Cannes Film Festival for "Kinatay." (Source: Bauer Griffin) “Captive” is about the kidnapping of a group of tourists by the fearsome Abu Sayaf group from a resort in Honda Bay, in Palawan. They are taken to Mindanao. -

Singsing- Memorable-Kapampangans

1 Kapampangan poet Amado Gigante (seated) gets his gold laurel crown as the latest poet laureate of Pampanga; Dhong Turla (right), president of the Aguman Buklud Kapampangan delivers his exhortation to fellow poets of November. Museum curator Alex Castro PIESTANG TUGAK NEWSBRIEFS explained that early Kapampangans had their wakes, funeral processions and burials The City of San Fernando recently held at POETS’ SOCIETY photographed to record their departed loved the Hilaga (former Paskuhan Village) the The Aguman Buklud Kapampangan ones’ final moments with them. These first-of-its-kind frog festival celebrating celebrated its 15th anniversary last pictures, in turn, reveal a lot about our Kapampangans’ penchant for amphibian November 28 by holding a cultural show at ancestors’ way of life and belief systems. cuisine. The activity was organized by city Holy Angel University. Dhong Turla, Phol tourism officer Ivan Anthony Henares. Batac, Felix Garcia, Jaspe Dula, Totoy MALAYA LOLAS DOCU The Center participated by giving a lecture Bato, Renie Salor and other officers and on Kapampangan culture and history and members of the organization took turns lending cultural performers like rondalla, reciting poems and singing traditional The Center for Kapampangan Studies, the choir and marching band. Kapampangan songs. Highlight of the show women’s organization KAISA-KA, and was the crowning of laurel leaves on two Infomax Cable TV will co-sponsor the VIRGEN DE LOS new poets laureate, Amado Gigante of production of a video documentary on the REMEDIOS POSTAL Angeles City and Francisco Guinto of plight of the Malaya Lolas of Mapaniqui, Macabebe. Angeles City Councilor Vicky Candaba, victims of mass rape during World COVER Vega Cabigting, faculty and students War II. -

Lopez Group Reiterates CSR Commitment At

Dec. 08-Jan. 09 Available online at www.benpres-holdings.com Christmas greetings from OML, MML and EL3 ...p. 5 Int’l banks show Lopez Group reiterates CSR commitment support for First at Clinton Global Initiative Meeting Gen, First Gas...p. 3 CHAIRMAN Oscar M. Lopez (OML) reiterated the Chairman Lopez and daughter Rina Lopez Group’s commitment to pursue corporate social receive the CGI Certificate of responsibility (CSR) projects that will improve the lives Acknowledgment presented by former of the marginalized, especially in causes for the environ- US President Clinton to Knowledge ment and education. Channel. He announced twin donations worth almost P420 million as the group’s “Commitment to Action” during the first Clinton Global Initiative (CGI) Asia Meeting in Hong Kong in early December. At the same time, the Knowledge Channel Foundation Inc. (KCFI) headed by Rina Lopez-Bautista was one of the six models of commitments presented by former US President Bill Clinton at the closing ceremonies of the CGI meet. Knowledge Channel received the highest commenda- tions from the former US President for its pioneering efforts to provide poor and marginalized but bright chil- dren in far-flung areas in the country free access to com- puter/Internet education. Clinton said the KCFI program should be replicated elsewhere in the world. “I would like to compliment them for what they’re doing A look back at 2008…p. 5 and for others to replicate this in their countries,” he said. Turn to page 7 PHOTO: ROSAN CRUZ ABS-CBN goes beyond TV WHO would have thought, back in Only a year later, in 1958, ABS- the mid-1950s, that a couple of fledg- CBN rolled out what would be the ing radio stations and a TV network first of many innovations under Don under the leadership of a man not Ening and his son Eugenio “Geny” yet 30 years old would grow into the Lopez Jr., then 28, who was tasked country’s largest media conglomerate? to run the company: the country’s ABS-CBN Broadcasting Corp. -

CBE Faculty Members Lend Business Expertise to GK

2401 (twen´te for´,o, wun) is a landmark number along Taft Avenue. It is the location ID of De La Salle University-Manila, home to outstanding faculty and students, and birthplace of luminaries in business, public service, education, the arts, and science. And 2401 is now the name of the official newsletter of DLSU-Manila, featuring developments and stories of interest about the University. 3 APRIL 2006. VOLUME 37. NUMBER 30. 8 PAGES CBE faculty Field Notes: members Puro Footnote lend business 4 Lamang sa 3 Kasaysayan expertise ng Pelikulang to GK Pilipino ni Dr. Clodualdo del Mundo, Jr. Alumni, student leaders strengthen network in Kapihang Lasalyano The Offi ce of Career Services and the them personally and professionally. It also vasio (DLSC GS ’64, LSGH Primus ’68, De La Salle Alumni Association organized aims to solicit specifi c suggestions from AB-BSC ’73); Eduardo Lucero (DLSC the fi fth “Kapihang Lasalyano,” an annual the alumni on student development and GS ’61, HS ’65, AB-BSC ’70); Adriel informal dialogue between distinguished formation. Peña (DLSC GS ’64, LSGH Primus ’68, alumni and select student leaders, on In choosing their career, the alumni COE ’73); Camilo Reyes (BSC ’69); Jose March 10 at the Br. Connon Hall. advised the student leaders to: 1) get a job Tanjuatco (DLSC GS ’64, LSGH Primus The activity was organized to provide they are passionate about; 2) decide with ’68, AB-BSC ’73); Benjamin the current crop of student leaders a venue their values; and 3) make the most of their Uichico (LSGH ’76, MFI); and Cornelio to learn from the alumni guests by draw- Lasallian education by continuing to be Vergara Jr.