Corporate Responsibility in the UK Construction Industry: a Study of Activities and Reporting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scott Wilson Scotland: a History Volume 11 the Interchange Years

Doc 12.56: Scott Wilson Scotland: A History: Vol 11: The Interchange Years 2005-2009 JP McCafferty Scott Wilson Scotland: A History Volume 11 The Interchange Years 2005-2009 Transcribed and edited from ‘Interchange’ JP McCafferty 1 Doc 12.56: Scott Wilson Scotland: A History: Vol 11: The Interchange Years 2005-2009 JP McCafferty Significant or notable projects, people and events are highlighted as follows for ease of reference:- Projects/Disciplines People Issue/Date Actions Contents Background ......................................................................................................................................... 12 Interchange ......................................................................................................................................... 12 JP McCafferty [Find Issues 1-40; Fix Pics P 16, 21; Fix P 68 150 Header 2]...................................... 12 Interchange 41 [21.10.2005] ............................................................................................................... 13 The Environment section in Edinburgh is delighted to welcome Nicholas Whitelaw ..................... 13 Interchange 42 [28.10.2005] ............................................................................................................... 13 S W Renewable Energy at British Wind Energy Association [Wright; Morrison] ............................. 13 Interchange 43 [4.11.2005] ................................................................................................................. 14 Jobs: Civil -

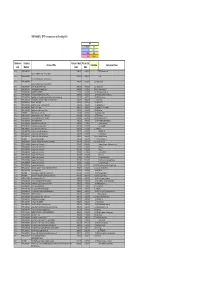

FOI F0009332 - DFT Live Contract As at 31St July 2012

FOI F0009332 - DFT live contract as at 31st July 2012 KEY DfT (C ) DSA HA DVLA VOSA MCA VCA GCDA Business Contract Contract Start Actual End Contract Title Let Value Contractor Name Unit Number Date Date DfT(c) PPRO 04/084/002/ 31/08/2011 30/08/2013 BFBS Consultants Ltd Overseas Aviation Security Training 2 (OAST2) DfT(c) PPRO 04/084/002/ 31/08/2011 30/08/2013 Redline Overseas Aviation Security Training 2 (OAST2) DfT(c) PPRO 04/084/002/ 31/08/2011 30/08/2013 £950,000 Ronalt Ltd Overseas Aviation Security Training 2 (OAST2) DfT(c) PPRO 04/047/061/ 2ND TRANCHE LAPTOPS 4 HS2 02/07/2012 01/08/2012 £223,230 SCC LTD DfT(c) PPRO 04/005/018/ AADFS Migration and Hosting Project 08/06/2006 31/12/2012 £362,933 1Spatial Limited DfT(c) PPRO 04/027/054/ ADOBE ELIR LICENSING 23/11/2011 22/11/2012 £101,769 Insight Direct (UK) Ltd DfT(c) PPRO 04/063/006/ ALFRESCO SUPPORT & MAINTENANCE 01/04/2010 31/03/2013 £99,414 ALFRESCO SOFTWARE LTD DfT(c) PPRO 04/023/012/ Appointment of Professional Advisers for RAIB relocation to Farnborough 25/11/2011 24/05/2013 £106,000 Capita Symonds DfT(c) PPRO 04/006/036/ Archiving Police Fatal Road Accident Traffic Reports - Phase 7 10/10/2011 09/09/2012 £112,110 TRL Ltd DfT(c) PPRO 04/047/062/ B-CRYPT SOFTWARE 28/06/2012 27/06/2013 £33,652 SCC LTD DfT(c) PPRO 04/048/019/ Bloomberg Subscription and Terminal Hire 16/02/2011 15/02/2013 £35,000 Bloomberg LP DfT(c) PPRO 04/063/007/ BOW TIE TELEVISION 01/04/2012 31/03/2013 £25,000 BOW TIE TELEVISION DfT(c) PPRO 04/024/017/ British Social Attitudes Survey 2012 -14 13/03/2012 12/03/2015 -

Build to Last Annual Report and Accounts 2017 Contents

Build to Last Annual Report and Accounts 2017 Contents Strategic Report Chairman’s introduction 02 The transformation of Group Chief Executive’s review 04 Group at a glance 06 Balfour Beatty is Market review 08 well underway Business model 10 Our priorities 12 What we have been doing in 2017 16 Group Chief Directors’ valuation of the Executive’s review Investments portfolio 26 p04 Building a sustainable business 29 Measuring our performance 38 Chief Financial Officer’s review 44 Risk management framework 48 Performance review Principal risks 51 by segment Viability statement 57 Governance Chairman’s introduction 58 What we have been Leadership 60 doing in 2017 Effectiveness 63 p16 Accountability 67 Directors’ report – other disclosures 72 Remuneration report 76 Acting responsibly to protect Financial Statements and enhance the Independent auditor’s report 88 Financial statements 94 environment and support Notes to the financial statements 102 local communities Other Information Building a sustainable business Unaudited Group five-year summary 174 p29 Shareholder information 175 Front cover images (clockwise): Dorenell wind farm: this £20 million overhead line will connect a key Scottish wind farm to the national grid. Cooper’s Hill retirement development: this luxury facility includes 78 retirement properties, a health club, swimming pool, restaurant and library. The Dallas Horseshoe: following a distinctive U-shaped path, this design-build project upgraded 73 miles of road and 37 bridges to reduce congestion in Dallas, Texas. Balfour Beatty Annual Report and Accounts 2017 Strategic Report Governance Financial Statements Other Information 01 2017 progress Build to Last Lean Today, Balfour Beatty is well placed to drive £335m 2016: £173m sustainable profitable growth, underpinned Net cash excluding by a strong balance sheet. -

Formal Minutes

House of Commons Business, Innovation and Skills Committee Formal Minutes Session 2010–12 Business, Innovation and Skills Committee The Business, Innovation and Skills Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills. Current membership Mr Adrian Bailey MP (Labour, West Bromwich West) (Chair) Mr Brian Binley MP (Conservative, Northampton South) Paul Blomfield MP (Labour, Sheffield Central) Katy Clark MP (Labour, North Ayrshire and Arran) Julie Elliott MP (Labour, Sunderland Central) Rebecca Harris MP (Conservative, Castle Point) Margot James MP (Conservative, Stourbridge) Simon Kirby MP (Conservative, Brighton Kemptown) Ann McKechin MP (Labour, Glasgow North) Mr David Ward MP (Liberal Democrat, Bradford East) Nadhim Zahawi MP (Conservative, Stratford-upon-Avon) The following members were also members of the Committee during the parliament. Luciana Berger MP (Labour, Liverpool, Wavertree) Jack Dromey MP (Labour, Birmingham, Erdington) Dan Jarvis MP (Labour, Barnsley Central) Gregg McClymont MP (Labour, Cumbernauld, Kilsyth and Kirkintilloch East) Nicky Morgan MP (Conservative, Loughborough) Chi Onwurah MP (Labour, Newcastle upon Tyne Central) Rachel Reeves MP (Labour, Leeds West) Ian Murray MP (Labour, Edinburgh South) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the internet at www.parliament.uk/parliament.uk/bis. -

Top 100 Engineers

40topengineersdr 5/10/10 15:51 Page 52 TOP 100 ENGINEERS Rank Practice Engineering staff Total UK Total UK staff Offices chartered staff 2009 2010 Total Civil Structural Mechanical Electrical Other 2009 2010 2009 2010 UK Worldwide 1 1 Atkins 2,490 1,124 254 281 260 571 4,013 3,625 11,950 10,620 126 238 2 2 Mott MacDonald 1,710 960 190 190 320 50 2,800 2,555 6,100 5,950 34 137 3 3 Scott Wilson Group 1,378 845 126 52 91 264 1,658 1,473 3,476 3,109 39 79 8 4 Arup Group 1,202 528 281 190 109 94 1,373 1,334 4,358 3,986 17 85 4 5 Halcrow Group 1,151 914 120 72 45 1,517 1,225 4,223 3,842 24 97 9 6 WSP Group 1,076 279 258 161 97 281 1,232 1,111 2,791 2,459 23 273 10 7 Capita Symonds 856 249 127 46 32 402 1,662 1,826 4,029 4,611 64 69 12 8 Parsons Brinckerhoff 692 254 27 98 182 131 769 872 1,871 2,138 16 19 11 9 Waterman Group 624 362 125 59 18 60 653 624 1,081 923 24 37 – 10 WYG Group 489 146 119 37 33 154 873 701 2,082 1,669 25 58 16 11 Buro Happold 315 26 99 44 29 117 370 323 1,051 964 8 27 – 12 Grontmij 294 225 10 8 30 21 514 310 1,302 913 19 33 – 13 Hoare Lea & Partners 252 0 0 162 83 7 222 252 511 516 10 11 17 14 WA Fairhurst & Partners 220 145 38 0 0 37 267 242 480 407 14 14 18 15 Mace 200 100 10 90 0 821 939 2,054 2,178 11 25 19 16= TPS 178 97 29 16 15 21 363 337 461 428 7 8 23 16= Ramboll UK 178 10 77 19 14 58 205 181 560 446 11 11 28 18 EC Harris 159 23 89 47 1,638 1,682 2,295 2,193 15 44 20 19 Gifford 147 71 26 17 3 30 177 148 731 605 10 14 22 20 BDP 138 1 34 67 36 0 619 551 1,168 1,032 10 17 27 21 Hurleypalmerflatt 136 0 6 57 53 20 -

Report and Accounts 2010

Report and Accounts 2010 Local knowledge international expertise rpsgroup.com We are an international consultancy providing expert advice upon: the exploration the development the management and production of land, property of the environment of energy and and infrastructure and the health other natural and safety of people resources Energy Planning & Development Environmental Management Local knowledge Successful partners international expertise delivering quality results Report and Accounts 2010 3 Business Review 8 Management & Governance 41 2010 Results 8 Key Performance Indicators 8 The Board 42 Operations 25 Committees 43 Risk Management 31 Corporate Governance 44 Corporate Responsibility 37 Accounts 61 Report of the Directors 62 Report of the Independent Auditors 67 Consolidated Income Statement 68 Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 68 Consolidated Balance Sheet 69 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 70 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 71 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 72 Parent Company Balance Sheet 107 Notes to the Parent Company Financial Statements 108 Five Year Summary 115 Creative people Trusted leaders making a difference of our professions rpsgroup.comrpsgroup.com 4 An effective international presence Report and Accounts 2010 RPS employs around 4,500 people in the UK, Ireland, 5 An effective the Netherlands, the United States, Canada, Brazil, Africa, Australia and Asia. Our truly international presence allows us to undertake co-ordinated and international presence integrated projects throughout the world. Our strategy has been to broaden our range of services and our geographical spread. Since the beginning of 2009 we have undertaken projects in over 120 countries across six continents. n RPS is a remarkable business. Whilst the world has been in the grips of financial and economic turbulence we have progressed calmly and effectively. -

Sector Report Rail Saudi Arabia

Railways – Saudi Arabia Sector Report Rail Saudi Arabia Produced by: Abdul Muqtadar Trade & Investment Officer British Consulate General – Jeddah Last revised: 05 May 2010 Whereas every effort has been made to ensure that the information given in this document is accurate, neither UK Trade & Investment nor its parent Departments (the Department for Business, innovation and Skills and the Foreign & Commonwealth Office), accept liability for any errors, omissions or misleading statements, and no warranty is given or responsibility accepted as to the standing of any individual, firm, company or other organisations mentioned. Published by UK Trade & Investment www.uktradeinvest.gov.uk Railways – Saudi Arabia Table of Contents OVERVIEW 3 CHARACTERISTICS OF MARKET 4 KEY METHODS OF DOING BUSINESS 13 PUBLICATIONS 14 EVENTS 15 CONTACT LISTS 15 APPENDIX 16 www.uktradeinvest.gov.uk Page 2 of 18 Railways – Saudi Arabia OVERVIEW The idea of building railways in Saudi Arabia started in mid fifties of last century when a need for a commercial seaport in the gulf coast emerged. The current railway was inaugurated in 1951. Saudi Railways Organisation (SRO), the national entity for railways was established according to a royal decree in 22/2/1386 (12 Jun 1966). Currently, there is a single railway that links Dammam in the Eastern Province with Riyadh, the capital. Saudi Arabia's ambition of a better and bigger railway is starting to come into life with the new huge railway projects in the Western and Eastern regions of the Kingdom. The construction of the railway project connecting Jeddah, Makkah, and Madinah kicked off in June 2009. -

Annual General Meeting 2021

1 This document is important and requires your immediate attention, so please read it straight away. If you are in any doubt as to any aspect of the proposals referred to in this document or as to the action you should take, you should consult your stockbroker, bank manager, solicitor, accountant or other professional advisor authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000. If you have sold or transferred your shares in Balfour Beatty plc, please send this circular and the accompanying Form of Proxy to the person who sold or transferred the shares for you so they can be passed on to the person who now owns the shares. Annual General Meeting 2021 Dear shareholder In addition to the standard matters, shareholders who have voted, based on the shareholders are being asked to approve the number of shares they hold. The results will “Balfour Beatty Performance Share Plan 2021” be published on the Company’s website as I am pleased to send you details of the (resolution 16), which is a replacement for the soon as practicable after the meeting. Annual General Meeting (AGM) of Balfour Balfour Beatty Performance Share Plan 2011, Beatty plc (Balfour Beatty or the Company), This year, shareholders must nominate the which was approved by shareholders at the which will be held at 10:00am on Thursday 13 Chair of the meeting as their proxy in order 2011 annual general meeting and, in line with May 2021 at The Curve Building, Axis for their votes to be counted. For your proxy usual practice and the approval given in 2011, Business Park, Langley, Berkshire, SL3 8AG. -

Building on Scott Wilson's 60 Years of Innovation and Design Excellence

aving been acquired by URS Hin 2010, one of Hong Kong's major consultants, Scott Wilson, rebranded as URS last month. Headquartered in San Francisco, URS is one of the world's leading providers of design, engineering, construction and technical services. The company specialises in full lifecycle services for clients Building on across a broad range of industry sectors, as well as public sector Scott Wilson's agencies and contractors. The company is publicly owned and 60 years of listed on the New York Stock Exchange as URS, with fiscal 2012 innovation and revenues at US$10.97 billion - a 15% increase from fiscal 2011. design excellence As an integrated services provider, URS has the global reach, local knowledge and sector expertise required to meet the most complex and challenging assignments, while using innovative and sustainable design that values the natural environment and enhances communities. In Hong Kong, URS is building on Scott Wilson's 60 years of innovation and design excellence, along with its associated company, URS Benaim's unique strengths in value engineering and construction engineering services. With this strong local foundation, URS is expanding its sustainable business to serve clients in Hong Kong, China and throughout the Asia-Pacific region. BUILDING JOURNAL 39 COMPANY PROFILE Interview with Dr Mark Raiss, URS Managing Director, Hong Kong & South East Asia Could you tell us a little about the consultancies include packages on the history of the company? MTR Corporation's South Island Line With a history stretching back to 1904, and Shatin to Central Link, and the URS has played a role in the engineering Macau LRT. -

The Case of UK

Corporate governance and firm performance: the case of UK. Accounting and Finance department Business school University of Portsmouth ALI FARHAT A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Director of studies: Richard Trafford JULY 2014 1 Acknowledgment My appreciation goes to Richard Trafford, my supervisor, for his encouragement, support, time, and valuable comments on this study. I am very grateful for the opportunity to work with him as have learned a great deal from his knowledge and experience. I would like to thank Professor Michael Page for his comments and feedbacks on this study which were very helpful. I would like to express my indebtedness to the Al Tajer Trust, which provided me with all the assistance and financial support for my scholarship. I am grateful to all my family and friends, especially Mr Brian Johnson, for kindly supporting me during my stay and study at University of Portsmouth. Finally, many thanks go to all staff members and the faculty research team at Portsmouth Business School for their help during the completion of this thesis. 2 Declaration “Whilst registered as a candidate for the above degree, I have not been registered for any other research award. The results and conclusions embodied in this thesis are the work of the named candidate and have not been submitted for any other academic award”. Signature………………………….. Date……………………………….. 3 Abstract The subject of corporate governance and corporate performance has been widely discussed and examined over the last two decades. A great deal of change has developed within British Boardrooms since the emergence of the Cadbury Committee Report in 1992. -

Attention - All Staff! Bob Mcgowan from Geoff French

th Issue 361 Week ending: 6 September 2002 Attention - All Staff! Bob McGowan From Geoff French Bob McGowan retired last week after a long and distinguished career, most of which he spent with Scott Wilson. Bob graduated from the University of Strathclyde in 1960 and more than half of his career since than has been as a Partner and Director of Scott Wilson – a remarkable record. After an initial period in contracting which took him to Zambia, London and Canada Bob joined Scott Wilson in 1967. He than worked in Glasgow and Nairobi before moving to Basingstoke in 1994 and becoming Chairman of Scott Wilson in 1998. Bob’s career with Scott Wilson has included a wide range of projects in the UK and overseas. In and around Glasgow there are many projects for which he has been responsible including the Renfrew Motorway Stage I, Townhead Interchange Stage II, Ayr Motorway Stage I, Dumbreck Road Connection and structural investigations on the problems of the Kingston Bridge. He was also responsible for the design of some 50 new bridges for Abuja, the new capital city of Nigeria and for viaduct and elevated ramp designs for Tuen Mun New Town in Hong Kong. Bob’s period in charge of the Glasgow Office saw him being responsible also for a large number of projects including a section of the new M74, a two year planning study for Rosyth Naval Base, a feasibility study for a new railway in Scotland and an 85 metre prestressed concrete canal aqueduct. Since moving to Basingstoke Bob has concentrated primarily on corporate issues. -

Top International Design Firms 2010 Ranked By

Top international design firms 2010 ranked by ERN http://enr.construction.com/toplists/InternationalDesignFirms/001-100.asp, Based on Design Revenue from Projects Outside Home Country KEY TO TYPE OF FIRM: A=architect; E=engineer; EC=engineer-contractor; AE=architect-engineer; EA=engineer-architect; ENV=environmental; G=soils or geotechnical engineer; P=planner. Other combinations possible. Firms classified themselves. RANK FIRM NAME & LOCATION FIRM 2010 2009 1 1 Fugro NV, Leidschendam, The Netherlands† E 2 2 WorleyParsons, North Sydney, NSW, Australia† EC 3 6 AECOM Technology Corp., Los Angeles, Calif., U.S.A. EA 4 4 Fluor Corp., Irving, Texas, U.S.A.† EC 5 3 AMEC plc, London, U.K.† E 6 7 ARCADIS NV, Arnhem, The Netherlands† E 7 5 Jacobs, Pasadena, Calif., U.S.A. EAC 8 8 SNC-Lavalin International Inc., Montreal, Quebec, Canada† EC 9 10 Dar Al-Handasah Consultants (Shair & Partners), Cairo, Egypt EA 10 9 KBR, Houston, Texas, U.S.A.† EC 11 13 Tecnicas Reunidas, Madrid, Spain† EC 12 11 Bechtel, San Francisco, Calif., U.S.A.† EC 13 15 Mott MacDonald Group Ltd., Croydon, Surrey, U.K.† E 14 19 HOCHTIEF AG, Essen, Germany† EC 15 ** TECHNIP, Paris la Defense, France† EC 16 26 CH2M HILL, Englewood, Colo., U.S.A.† EC 17 21 Louis Berger Group, Morristown, N.J., U.S.A.† EAP 18 17 ARUP Group Ltd., London, U.K.† E 19 18 Hatch Group, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada† E 20 62 CB&I, The Woodlands, Texas, U.S.A.† EC 21 14 Poyry, Vantaa, Finland† E 22 16 WSP Group plc, London, U.K.† E 23 22 Parsons Brinckerhoff Inc., New York, N.Y., U.S.A.† EA 24 20 URS Corp.,