Polarization II: Waveplates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Processor U.S

USOO5926295A United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: 5,926,295 Charlot et al. (45) Date of Patent: Jul. 20, 1999 54) HOLOGRAPHIC PROCESS AND DEVICE 4,602,844 7/1986 Sirat et al. ............................. 350/3.83 USING INCOHERENT LIGHT 4,976,504 12/1990 Sirat et al. .. ... 350/3.73 5,011,280 4/1991 Hung.............. ... 356/345 75 Inventors: Didier Charlot, Paris; Yann Malet, 5,081,540 1/1992 Dufresne et al. ... ... 359/30 Saint Cyr l’Ecole, both of France 5,081,541 1/1992 Sirat et al. ...... ... 359/30 5,216,527 6/1993 Sharnoff et al. ... 359/10 73 Assignee: Le Conoscope SA, Paris, France 5,223,966 6/1993 Tomita et al. .......................... 359/108 5,291.314 3/1994 Agranat et al. ......................... 359/100 21 Appl. No.: 08/681,926 22 Filed: Jul. 29, 1996 Primary Examiner Jon W. Henry Attorney, Agent, or Firm Michaelson & Wallace; Peter L. Related U.S. Application Data Michaelson; John C. Pokotylo 62 Division of application No. 08/244.249, filed as application 57 ABSTRACT No. PCT/FR92/01095, Nov. 25, 1992, Pat. No. 5,541,744. An optical device for generating a signal based on a distance 30 Foreign Application Priority Data of an object from the optical device. The optical device includes a first polarizer, a birefringent crystal positioned Nov. 27, 1991 FR France ................................... 91. 14661 optically downstream from the first polarizer, and a Second 51) Int. Cl. .............................. G03H 1/26; G01B 9/021 polarizer arranged optically downstream from the birefrin 52 U.S. Cl. ................................... 359/30; 359/11; 359/1; gent crystal. -

Lab 8: Polarization of Light

Lab 8: Polarization of Light 1 Introduction Refer to Appendix D for photos of the appara- tus Polarization is a fundamental property of light and a very important concept of physical optics. Not all sources of light are polarized; for instance, light from an ordinary light bulb is not polarized. In addition to unpolarized light, there is partially polarized light and totally polarized light. Light from a rainbow, reflected sunlight, and coherent laser light are examples of po- larized light. There are three di®erent types of po- larization states: linear, circular and elliptical. Each of these commonly encountered states is characterized Figure 1: (a)Oscillation of E vector, (b)An electromagnetic by a di®ering motion of the electric ¯eld vector with ¯eld. respect to the direction of propagation of the light wave. It is useful to be able to di®erentiate between 2 Background the di®erent types of polarization. Some common de- vices for measuring polarization are linear polarizers and retarders. Polaroid sunglasses are examples of po- Light is a transverse electromagnetic wave. Its prop- larizers. They block certain radiations such as glare agation can therefore be explained by recalling the from reflected sunlight. Polarizers are useful in ob- properties of transverse waves. Picture a transverse taining and analyzing linear polarization. Retarders wave as traced by a point that oscillates sinusoidally (also called wave plates) can alter the type of polar- in a plane, such that the direction of oscillation is ization and/or rotate its direction. They are used in perpendicular to the direction of propagation of the controlling and analyzing polarization states. -

Principles of Retarders

Polarizers PRINCIPLES OF RETARDERS etarders are used in applications where control or Ranalysis of polarization states is required. Our retarder products include innovative polymer and liquid crystal materials. Crystalline materials such as quartz and Retarders magnesium fluoride are also available upon request. Please call for a custom quote. A retarder (or waveplate) is an optical device that resolves a light wave into two orthogonal linear polarization components and produces a phase shift between them. The resulting light wave is generally of a different polarization form. Ideally, retarders do not polarize, nor do they induce an intensity change in the Crystals Liquid light beam, they simply change its polarization form. state. The transmitted light leaves the retarder elliptically All standard catalog Meadowlark Optics’ retarders are polarized. made from birefringent, uniaxial materials having two Retardance (in waves) is given by: different refractive indices – the extraordinary index ne = tր and the ordinary index no. Light traveling through a retarder has a velocity v where: dependent upon its polarization direction given by  = birefringence (ne - no) Spatial Light Modulators v = c/n = wavelength of incident light (in nanometers) t = thickness of birefringent element where c is the speed of light in a vacuum and n is the (in nanometers) refractive index parallel to that polarization direction. Retardance can also be expressed in units of length, the By definition, ne > no for a positive uniaxial material. distance that one polarization component is delayed For a positive uniaxial material, the extraordinary axis relative to the other. Retardance is then represented by: is referred to as the slow axis, while the ordinary axis is ␦Ј ␦  referred to as the fast axis. -

Optical and Thin Film Physics Polarisation of Light

OPTICAL AND THIN FILM PHYSICS POLARISATION OF LIGHT An electromagnetic wave such as light consists of a coupled oscillating electric field and magnetic field which are always perpendicular to each other; by convention, the "polarization" of electromagnetic waves refers to the direction of the electric field. In linear polarization, the fields oscillate in a single direction. In circular or elliptical polarization, the fields rotate at a constant rate in a plane as the wave travels. The rotation can have two possible directions; if the fields rotate in a right hand sense with respect to the direction of wave travel, it is called right circular polarization, while if the fields rotate in a left hand sense, it is called left circular polarization. On the other side of the plate, examine the wave at a point where the fast-polarized component is at maximum. At this point, the slow-polarized component will be passing through zero, since it has been retarded by a quarter-wave or 90° in phase. Moving an eighth wavelength farther, we will note that the two are the same magnitude, but the fast component is decreasing and the slow component is increasing. Moving another eighth wave, we find the slow component is at maximum and the fast component is zero. If the tip of the total electric vector is traced, we find it traces out a helix, with a period of just one wavelength. This describes circularly polarized light. Left-hand polarized light is produced by rotating either the waveplate or the plane of polarization of the incident light 90° . -

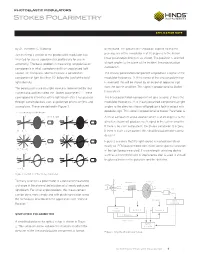

Stokes Polarimetry

photoelastic modulators Stokes Polarimetry APPLICATION NOTE by Dr. Theodore C. Oakberg beforehand. The polarimeter should be aligned so that the James Kemp’s version of the photoelastic modulator was passing axis of the modulator is at 45 degrees to the known invented for use as a polarimeter, particularly for use in linear polarization direction, as shown. The polarizer is oriented astronomy. The basic problem is measuring net polarization at right angles to the plane of the incident linear polarization components in what is predominantly an unpolarized light component. source. Dr. Kemp was able to measure a polarization The circular polarization component will produce a signal at the component of light less than 106 below the level of the total modulator frequency, 1f. If the sense of the circular polarization light intensity. is reversed, this will be shown by an output of opposite sign The polarization state of a light source is represented by four from the lock-in amplifi er. This signal is proportional to Stokes numerical quantities called the “Stokes parameters”.1,2 These Parameter V. correspond to intensities of the light beam after it has passed The linear polarization component will give a signal at twice the through certain devices such as polarized prisms or fi lms and modulator frequency, 2f. A linearly polarized component at right wave plates. These are defi ned in Figure 1. angles to the direction shown will produce a lock-in output with I - total intensity of light beam opposite sign. This signal is proportional to Stokes Parameter U. y DETECTOR y A linear component of polarization which is at 45 degrees to the I x x I x x direction shown will produce no 2f signal in the lock-in amplifi er. -

A Birefringent Polarization Modulator: Application to Phase Measurement in Conoscopic Interference Patterns F

A birefringent polarization modulator: Application to phase measurement in conoscopic interference patterns F. E. Veiras, M. T. Garea, and L. I. Perez Citation: Review of Scientific Instruments 87, 043113 (2016); doi: 10.1063/1.4947134 View online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4947134 View Table of Contents: http://scitation.aip.org/content/aip/journal/rsi/87/4?ver=pdfcov Published by the AIP Publishing Articles you may be interested in Enhanced performance of semiconductor optical amplifier at high direct modulation speed with birefringent fiber loop AIP Advances 4, 077107 (2014); 10.1063/1.4889869 Invited Review Article: Measurement uncertainty of linear phase-stepping algorithms Rev. Sci. Instrum. 82, 061101 (2011); 10.1063/1.3603452 Birefringence measurement in polarization-sensitive optical coherence tomography using differential- envelope detection method Rev. Sci. Instrum. 81, 053705 (2010); 10.1063/1.3418834 Phase Measurement and Interferometry in Fibre Optic Sensor Systems AIP Conf. Proc. 1236, 24 (2010); 10.1063/1.3426122 Note: Optical Rheometry Using a Rotary Polarization Modulator J. Rheol. 33, 761 (1989); 10.1122/1.550064 Reuse of AIP Publishing content is subject to the terms at: https://publishing.aip.org/authors/rights-and-permissions. Download to IP: 201.235.243.70 On: Wed, 27 Apr 2016 20:53:51 REVIEW OF SCIENTIFIC INSTRUMENTS 87, 043113 (2016) A birefringent polarization modulator: Application to phase measurement in conoscopic interference patterns F. E. Veiras,1,2,a) M. T. Garea,1 and L. I. Perez1,3 1GLOmAe, Departamento de Física, Facultad de Ingeniería, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Av. Paseo Colón 850, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires C1063ACV, Argentina 2CONICET, Av. -

Lab #6 Polarization

EELE482 Fall 2014 Lab #6 Lab #6 Polarization Contents: Pre-laboratory exercise 2 Introduction 2 1. Polarization of the HeNe laser 3 2. Polarizer extinction ratio 4 3. Wave Plates 4 4. Pseudo Isolator 5 References 5 Polarization Page 1 EELE482 Fall 2014 Lab #6 Pre-Laboratory Exercise Bring a pair of polarized sunglasses or other polarized optics to measure in the lab. Introduction The purpose of this lab it to gain familiarity with the concept of polarization, and with various polarization components including glass-film polarizers, polarizing beam splitters, and quarter wave and half wave plates. We will also investigate how reflections can change the polarization state of light. Within the paraxial limit, light propagates as an electromagnetic wave with transverse electric and magnetic (TEM) field directions, where the electric field component is orthogonal to the magnetic field component, and to the direction of propagation. We can account for this vector (directional) nature of the light wave without abandoning our scalar wave treatment if we assume that the x^ -directed electric field component and y^ -directed electric field component are independent of each other. This assumption is valid within the paraxial approximation for isotropic linear media. The “polarization” state of the light wave describes the relationship between these x^ -directed and y^ -directed components of the wave. If the light wave is monochromatic, the x and y components must have a fixed phase relationship to each other. If the tip of the electric field vector E = Ex x^ + Ey y^ were observed over time at a particular z plane, one would see that it traces out an ellipse. -

Polarization Optics

POLARIZATION OPTICS Retardation Plate Theory Multiple Order Waveplates Achromatic Waveplates A retardation plate is an optically transparent material which As linear polarization enters a crystal, both polarization compo- Using the previous equation, and given a required The wavelength dependence of the birefringence dictates that resolves a beam of polarized light into two orthogonal nents are oscillating in phase with one another. As they propa- retardance value, the necessary thickness of the waveplate the spectral range for the standard waveplate is approximately components; retards the phase of one component relative to gate they begin to fall out of phase due to the velocity differ- can be calculated. For standard waveplate materials, such 10 nm. To accommodate tunable sources or sources with larger the other; then recombines the components into a single ence. Upon exiting, the resultant polarization is some form of as quartz and magnesium fluoride, the calculated thickness spectral widths, a waveplate that is relatively independent of beam with new polarization characteristics. elliptical polarization due to the phase difference. Special polar- for a retardation value of a fraction of a wave would be on wavelength is required This is accomplished with achromatic ization cases can result if the overall phase difference is in multi- the order of 0.1 mm and too thin to manufacture. For this waveplates. ples of � (linear polarization) or �/2 (circular). reason a higher multiple of the required retardation is use to Birefringence place the thickness of the waveplate in a physically manu- An achromatic waveplate is a zero-order waveplate utilizing To better understand phase retardation, birefringence must facturable range. -

Lecture 7: Polarization Elements That We Use in the Lab. Waveplates, Rotators, Faraday Isolators, Beam Displacers, Polarizers, Spatial Light Modulators

Lecture 7: Polarization elements that we use in the lab. Waveplates, rotators, Faraday isolators, beam displacers, polarizers, spatial light modulators. Polarization elements are important tools for various experiments, starting from interferometry and up to quantum key distribution. This lecture is focused on the commercial polarization elements that one can buy from companies like Thorlabs, Edmund Optics, Laser Components etc. We will consider waveplates and rotators, for polarization transformations, beam displacers and polarization prisms, for the measurement of polarization states, and finally spatial light modulators, elements that use polarization for preparing structured light. 1. Waveplates. A waveplate (retardation plate) can be most simply made out of a piece of crystalline quartz, cut so that the optic axis (z) is in its plane. Quartz is a positive uniaxial crystal, ne no . Therefore, for light polarized linearly along the z-axis, the refractive index n ne , and the phase (and group) velocity is smaller than for light polarized orthogonally to z-axis ( n no ). One says that the z-axis is then ‘the slow axis’, and the other axis is ‘the fast axis’. The fast axis is sometimes marked by a flat cut (Fig.1). A multi-order plate. However, a plate of reasonable thickness (0.5 mm or thicker) will work only for a narrow bandwidth. Indeed, although at Fig.1 the last 2 lectures we assumed that the refractive index is wavelength- independent, in reality it depends on the wavelength. Moreover, even without dispersion the phase would be different for different wavelengths. For instance, at 600 nm, the birefringence is n 0.0091 , and at 700 nm, n 0.0090, nearly the same over 100 nm. -

Waveplate Analyzer Using Binary Magneto-Optic Rotators

Waveplate analyzer using binary magneto-optic rotators Xiaojun Chen1, Lianshan Yan1, and X. Steve Yao1, 2 1. General Photonics Corp. Chino, CA, 91710, USA Tel: 909-590-5473 Fax: 909-902-5535 2. Polarization Research Center and Key Laboratory of Opto-electronics Information and Technical Science (Ministry of Education), Tianjin University, Tianjin 300072, China *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Abstract: We demonstrate a simple waveplate analyzer to characterize linear retarders using magneto-optic (MO) polarization rotators. The all- solid state device can provide highly accurate measurements for both the retardation of the waveplate and the orientation of optical axes simultaneously. ©2007 Optical Society of America OCIS codes: (120.5410) Polarimetry; (080.2730) Geometrical optics, matrix methods; (060.2300) Fiber measurements; (260.5430) Polarization References and links 1. D. Goldstein, “Polarized light,” (Second Edition, Marcel Dekker, Inc., NY, 2003). 2. E. Collett, Polarized light: Fundamentals and Applications, (Marcel Dekker, New York, 1993) pp. 100-103. 3. H. G. Jerrard, “Optical compensators for measurement of elliptical polarization,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. 38, 35-59 (1948). 4. D. H. Goldstein, “Mueller matrix dual-rotating retarder polarimeter,” Appl. Opt. 31, 6676-6683 (1992). 5. E. Dijkstra, H. Meekes, and M. Kremers, “The high-accuracy universal polarimeter,” J. Phys. D 24, 1861- 1868 (1991). 6. P. A. Williams, A. H. Rose, and C. M. Wang, “Rotating-polarizer polarimeter for accurate retardance measurement,” Appl. Opt. 36, 6466-6472 (1997). 7. D. B. Chenault and R. A. Chipman, “Measurements of linear diattenuation and linear retardance spectra with a rotating sample spectropolarimeter,” Appl. Opt. 32, 3513-3519 (1993). -

Fiber Optic Variable Waveplate

All-Fiber Variable Waveplate FEATURES: APPLICATIONS: All-fiber Polarization control Simple current control State of polarization scanning Full cycle of Poincare sphere Component testing Low insertion loss Sensor systems High return loss Optical fiber polarimetry Phoenix Photonics variable waveplate is a compact, simple to operate, all-fiber device for wideband operation. Applying a current to the pins gives a controlled modification of the linear birefringence within the device. The input State of polarization can be changed through a full cycle of the Poincare sphere. Two options are available giving flexibility for different applications. Option 1 Single mode (SM) fiber input and output: This version provides a complete cycle of the Poincare sphere to be achieved the range of polarization states generated in the output fiber is dependent on the input SOP. waveplate SM fiber SM fiber Option 2 Polarization maintaining (PM) fiber input and output: This option includes an integrated fiber polarizer in front of the waveplate aligned to the slow axis of the input fiber. The role of the polarizer is to ‘clean’ the linear input state. The output is a PM fiber, in this case the output polarization state will give a full cycle of the great circle on the Poincare sphere. The output from the fiber can be varied through right and left circular and two orthogonal linear states. input polarizer waveplate output PM fiber PM fiber SPECIFICATION: Units Option 1 Option 2 Wavelength range1 nm 1300 - 1610 Insertion Loss2 dB <0.3 <1 PMD ps <0.05 - Return Loss dB >70 Maximum current mA 70 Maximum Voltage V 10 Operating Temperature Range 0C -5 to 70 Storage Temperature 0C -40 to +85 Fiber type SMF28 PANDA Input & Output Fiber Lengths mm 1000 Notes: 1. -

Waveplates Intro Windows

Waveplates Intro Windows � � Technical Notes . 222 Selection Guide . 225 � Prisms Multiple Order. 226 θ � �� Zero Order Lenses Crystal Quartz . 228 Mica . 230 Mirrors Polymer. 231 Beamsplitters First Order . 232 Dual Wavelength . 233 Waveplates Achromatic Air-Spaced. 234 Polarizers Polymer . 236 Polarization Rotators . 237 Components Ultrafast Etalons Filters Interferometer Accessories ���� ��������������������� Mounts Appendix ������� ���������� Index �������������� Waveplates Intro Technical Notes Waveplates operate by imparting unequal The slow and fast axis phase shifts are � � Windows phase shifts to orthogonally polarized field given by: components of an incident wave. This φs ω ω π λ λ = ns ( ) t/c = 2 ns ( )t/ � causes the conversion of one polarization φf = nf (ω)ωt/c = 2πnf (λ)t/λ Prisms state into another. where ns and nf are, respectively, the θ � indices of refraction along the slow and There are two cases: �� fast axes, and t is the thickness of the Lenses With linear birefringence, the index of waveplate. refraction and hence phase shift differs for two orthogonally polarized linear To further analyze the effect of a waveplate, polarization states. This is the operation we throw away a phase factor lost in Mirrors Figure 1. Orientation of the slow and fast axes measuring intensity, and assign the entire mode of standard waveplates. of a waveplate with respect to an X-polarized phase delay to the slow axis: input field. With circular birefringence, the index of iφ refraction and hence phase shift differs E2 = s(s · E1)e + f(f · E1) For a half waveplate: Beamsplitters φ = φ - φ = 2π(n (λ) - n (λ))t/λ 2 for left and right circularly polarized s f s f φ = (2m + 1)π, T|| = cos 2θ, and = 2π∆n(λ)t/λ 2 components.