The Polish Amiga Scene As a Brand Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A+ Incider Magazine July 1993

"Quality Computers' System& System 6 Bonus Pack... the SlyleWrrtar printer support -· ···.. ... Macinlosh, Apple OOS 3 3, and most cost-effective way to ··.lit Apple Pascal disk support A completely redes1gned Finder add value and fun to laster. rrrendlier, and more power lullhan ever be lore, your Apple HGS." The Finder can be set to av01d grinding your s.2s· drive:; - Tfte AppleWork s Educator When Ihe ®rnPUier. askJI yp~ to - Insert a disk it needs. you no longer h~ve ID hit Re1urn-the computer delects it aufami!tically. Bonus Pack The screen no longer switches to FlashBoot. What is raster than a lexl mode and back ta graphics speeding disk drive? A RAM disk. when launchtng some Desktop AashBoollels you automatically set up programs a super-last. super-convenient RAM New mustc tools and applica disk. tions to allow nw. programs to sound even lletfe1 The Apple II Enhancement ......__ ~ Media-control toolset and des~ accessory to al- Guide. This handy filM book Is ~ :~ c::';'"' Desk low easter tnlegrntlor ol packed with inlormation to help ~ ~·"' • vtdeo with your multime- you upgrade your Apple II. II Accessories. Just to dia presentations give you more to choose covers RAM. hard drives. accel Universal Access fea erators. the Finder. and more. lrorn, we·re giving you tures for physically several handy desk acces handicapped users Clip Art. We're throwing In over sories including· Enhanced More 1oors tor pr~ 100 beauhlul clip art images, per Calculator, Scrapbook, Games. and grammcrs1o wr1te fect lor desktop publishing or hy more. great programs. permedia applications. -

Download, Including1 17N REU, Ramlink Partition, Jimymon-64 (ML Monitor)

C 0 T E T S ISSUE Published June 1996 COMMODORE WORLD 6 Wheels-Laying More Than A Patch THE NEWS MAGAZINE FOR COMMODORE 64 » 1'■ I 1J',[ K1. Bruce Thonuu 14 GOFA-A Modulap- Pcogpamming System Fob The Coeimodore 64 http://wviw.cmiweb.am/cwhtme.hlml George Flanagan General Manager Chinks ft Christiansen ♦ Editor Review; Doug Cot Ion ♦ 24 Software: Centipede 126 E>r Gaelwe R. Gasson Advegtisinq Sales A Look ai ihe Newesi Commodore I2S BBS Program Charles A. Christiansen (413) 525-0023 ♦ Graphic Acts Doug Cotton .UMN! '♦ 26 Jusr Fob Starters by Jason Compton Electronic Pre-Press & Pointing Maiuir/Holden Helpful Hints for Handling Disk Drives ♦ 30 Graphic Interpretation by Bruce Thomas Cover Design by Doug Cotton GEOS: For ti Good lime... 32 Carrier Detect by Gaelyne B. Gasson Tclecommunicationi News & Updates 36 S16 Beat by Mark Fellows Things to Look Out For When Program/Hint- the 65X16 Commodore1" and [he respective Commodore producl names are trademarks or registered trademarks of Commodore, a 38 Over The Edge by Jeffrey L. Jones division of Tulip Compulers. Commodore World is in no way aftiliated wilrtthe owner n! ".he Commodore logo ana technology. Commodore Programming in a SuperCPU World Commodore Worla (ISSN 1078-2515) is published 8 limos annually by Creative Micro Designs. Inc.. 15 Benton Drive, Easl Longrneadow MA 01028-0646. Secono-Class Postage Paid at EasL Longmeaflow MA. (USPS «)n-801| Annual subscnpiion rale is USS29.95 fci U.S. addresses. USS35.95(orC3nada0'Maiico.USSJS.95!orallECCounlnB5. Department paymanlsmusl be provided in U S. Dollars. Mail subscriptions 2 From the Editor to CW Subscriptions, do Crestiva Micro Designs. -

Computer Demos—What Makes Them Tick?

AALTO UNIVERSITY School of Science and Technology Faculty of Information and Natural Sciences Department of Media Technology Markku Reunanen Computer Demos—What Makes Them Tick? Licentiate Thesis Helsinki, April 23, 2010 Supervisor: Professor Tapio Takala AALTO UNIVERSITY ABSTRACT OF LICENTIATE THESIS School of Science and Technology Faculty of Information and Natural Sciences Department of Media Technology Author Date Markku Reunanen April 23, 2010 Pages 134 Title of thesis Computer Demos—What Makes Them Tick? Professorship Professorship code Contents Production T013Z Supervisor Professor Tapio Takala Instructor - This licentiate thesis deals with a worldwide community of hobbyists called the demoscene. The activities of the community in question revolve around real-time multimedia demonstrations known as demos. The historical frame of the study spans from the late 1970s, and the advent of affordable home computers, up to 2009. So far little academic research has been conducted on the topic and the number of other publications is almost equally low. The work done by other researchers is discussed and additional connections are made to other related fields of study such as computer history and media research. The material of the study consists principally of demos, contemporary disk magazines and online sources such as community websites and archives. A general overview of the demoscene and its practices is provided to the reader as a foundation for understanding the more in-depth topics. One chapter is dedicated to the analysis of the artifacts produced by the community and another to the discussion of the computer hardware in relation to the creative aspirations of the community members. -

United States District Court Southern District of Florida

Case 1:09-cv-21597-EGT Document 241 Entered on FLSD Docket 06/07/11 11:35:29 Page 1 of 34 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA Case No. 09-21597-CIV-TORRES CONSENT CASE KERNAL RECORDS OY, Plaintiff, vs. TIMOTHY Z. MOSLEY p/k/a TIMBALAND; et al., Defendants. ___________________________________________/ MEMORANDUM OPINION AND FINAL ORDER ON DEFENDANTS’ MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND PLAINTIFF’S MOTION TO AMEND On March 31, 2011, we issued a non-final Order granting Defendants Timothy Z. Mosley p/k/a Timbaland and Mosley Music, LLC’s (“Defendants”) Motion for Summary Judgment [D.E. 137]. [D.E. 227]. The underpinnings of the ruling were our conclusions that Plaintiff’s SID file version of “Acid Jazzed Evening” (“AJE”) had first been published on the Internet and that that act constituted simultaneous publication in the United States and other nations around the world having Internet service under the Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. § 501, et seq. We concluded that Plaintiff’s work met the definition of a “United States work” under 17 U.S.C. § 101(1)(C) and that, pursuant to 17 U.S.C. § 411(a), Plaintiff was required to register AJE prior to suing for copyright infringement. As there was no dispute that Plaintiff had failed to obtain a Case 1:09-cv-21597-EGT Document 241 Entered on FLSD Docket 06/07/11 11:35:29 Page 2 of 34 copyright registration for AJE or for any claimed “sound recording” or “composition,” we found that Plaintiff had not satisfied a statutory condition precedent to initiating this infringement lawsuit. -

OS-9 Newsletter Volume III Issue 7 Jul 31, 1992

OS-9 Newsletter Volume III Issue 7 BellinghamOS·9 Users Group July 31, 1992 Burke & Burke's 2. Breakpoints for both Emulation and 32MHz Crystal Native modes 3. New command to toggle read-back Clock Patch "The 6309 Book" of data after modification For those of you who installed a 4. New command to allow use of ""',. to 32:MHz crystal to speed up your CoCo examine or modifY memory any Dec'91 OS-9 Newsletter). ... Have you Everyone seems pretty excited about the address: '* 1 0 allows acces noticed vour clock is running fast? Hitachi 6309 replacement for the 6809 to the 089 direct page system The •solution is to reduce the tick processor chip in the Color Computer 3. variables. count from 60 ticks/second to about People are buying up Chris Burke's Power 5. All debugger variables are in high 60"'28/32 to compensate for the 32Mhz Boost package ($29.95) fasterthan he can memory so that it can debug crystal. Run the stock software 50 and get them produced. The companion programs that use low-memory package, 6309 Book by Burke and Burke 60Hz clocks through the 'cmp' absolute addressing. command. What I get follows below: ($24.95) , is just now starting to be Differences: (#1 � 50Hz. #2 60Hz) received in the mail by those who ordered The following utilities are also byte #1 #2 it two months ago. The book also comes included on the disk: with a disk containing some other 6309 Ezgen 1.09, is used to patch your Level 00000083 32 3C goodies, but what are they. -

CONTENTS As Promised Last Month, This Issue Contains Quite a Lot Page Item Downloaded from the Internet

geoNEWSthe Journal of geoCLUB Issue 72 August 1997 EDITOR’S COMMENTS CONTENTS As promised last month, this issue contains quite a lot Page Item downloaded from the Internet. I am reproducing 2 Library Review these for two main reasons ; Firstly : so that Terry& Sharon anyone who is interested can see just how much 3 Printer Cable information is out there for their out of date 8- Colin J Thomson bit machine. Secondly ; for those who, for one 4 8-Bit Server reason or another are unable to access the Marko Makela Internet will have a chance to see and read some of what is there. On pages 4 to 6 is a whole list 5 Other Users Marko Makela of other C64 orientated WWW sites, these all Home Page have a box (□) in front of them, this signifies 7 CUCUG C.U.C.U.G. that this is also a LINK, which means if you click on here with your mouse button the address is 8 CBM 1084 Spec. Internet Download automatically loaded into the URL address line and you are transported there with no more 9 Ramdom Access Dale Lutes effort than this.If anyone sees a link that they would like to see more of then please drop me a 11 Jerry’s Comer Jerry Shook line I will try to reproduce that page in a future issue. On Page 7 is a sample Club Web Site, I 12 August Dates chose this at random purely as a sample. I also downloaded the transcript of a meeting held in 1995 of an Amiga forum, regrading an auction for the purchase of CBM which as we all now know was ‘won’ by ESCOMM. -

Issue 95 CONTENTS Editorial Page 3 Growing Pains Part Siv Page 26 Where I Learned to Code in Style by Lenard R Roach

A free to download Magazine dedicated to Commodore computers. Issue 95 www.commodorefree.com CONTENTS Editorial Page 3 Growing Pains Part Siv Page 26 Where I Learned To Code In Style By Lenard R Roach General News Page 5 DUBCRT Commodore 64 Page 30 Limited Cartridge (PAL only) HARDWARE REVIEW Amiga News Page 8 DUBCART Page 32 Interview with Tim Koch Commodore 16/ plus4 News Page 12 Growing Pains Part Sex - Page 36 "The Program That Never Was" by Lenard R. Roach Commodore 64 News Page 14 Space Chase on the PET Page 38 The 35 year old review Vic 20 News Page 20 Commodore S.I.D chip Page 23 Interview with Andreas Beermann Page 25 Creator of FPGASID Commodore Free Magazine Page 2 www.commodorefree.com Editorial Welcome to another issue! I have been working hard, Editor but sadly in real life again and not in my virtual life. Nigel Parker Anyway, in this issue we have some real treats. Lena- rd R. Roach gives us more of his Commodore growing pains Spell Checking with a special double installation in this issue. Peter Badrick We have a review of the PET game Space Chase with some Bert Novilla complex SID music, “SID on the PET”! What’s this? Well, you need to read the review to find out more. TXT, HTML & eBooks Paul Davis We have a review of the truly weird Dubcart (cartridge). This is classed as an interactive music album for the Commodore 64. Plug into your machine and watch the petscii art and tru- D64 Disk Image ly exotic SID music. -

Hi Quality Version Available on AMIGALAND.COM

Issue 1 PAW ! oct 1 9 9 6 Hi Quality Version Available on AMIGALAND.COM 'an comI ain mah Oct 1996 A p pA ssign - quickly sort out new assigns M acW B • transforms your Workbench P opper - fix program menus on screen ftafftmafi • great new trathcan VMM - the best virtual memory manage 977095996308410 PindC U l - search for those files A -Stert - great looking start bar MMMMPWWM Now comj RAB... Rapid Frame with bo’J and V ing on your Amiga The revolutionary S-VHS ProGrab™ 24RT Plus with Teletext is not only the bei to get crisp colour video images into your Amiga, from either live broadcai taped recordings, it also costs less than any of its rivals. This real time I SECAM/NTSC* 24-Bit colour frame grabber/digitiser has slashed the pid image grabbing on the Amiga and, at the same time, has received rave i for its ease of use and exce lent quality results. ProGrab™ has earned hi from just about every Amiga magazine and Video magazines too! A n d ... w ith ProGrab™ you needn't be an expert in A m ig a V ideo Technol^ a simple 3 stage operation ensures the right results - Real Time, after S T A G E 1 ... Select any video source with S-VHS or composite output This could be your camcorder. TV with SCACT J satellite receiver, domestic VCR/ptiyer or standard TV signal oasvng through your VCR/player... the choice ii] S T A G E 2 ... With ProGrab's software, select an i n wish to capture using the on screen® Gr.ih inwges with your carry orde1 window and Grab (because the hctdn including S-VHS grabs frames in real time, there's non a freeze frame facility on the sourCa Once grabbed, simpty download a n ff full image on your Amiga screen. -

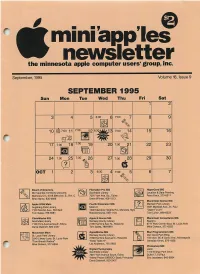

Mini Apples Newsletter the Minnesota Apple Computer Users' Group, Inc

0 @ mini apples newsletter the minnesota apple computer users' group, inc. September, 1995 Volume 18, Issue 9 SEPTEMBER 1995 Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat 6:30 6 7:00 7 8 10 @7:00 11 7:00 7:00 14 15 16 rAp| Mlr=il7:00 AM 17 7:00 18 7:00 19 20 7:00 21 22 23 24 7:00 25 7:00 26 27 7:00 28 29 30 9 |D| 6 OCT 1 6:30 4 7:00 . 5 ?V5 Board of Directors Filemaker Pro SIG HyperCard SIG Mini'app'les members welcome. Southdale Library Location & Date Pending Mathews Ctr., 2318 29th Ave. S., Rm. C ^ 7001 York Ave. So., Edina Peter Fleck, 370-0017 Brian Bantz, 835-3696 SteveWilmes, 458-1513 Macintosh Novice SIG Apple ll/GS Main Fourth Dimension SIG Merriam Park Library Augsberg Park Library, Metro II 1831 Marshall Ave., St. Paul J 7100 Nicollet Ave., Richfield 1300 Mendota Heights Rd., Mendota Hgts "Open Forum" TomGates, 789-6981 Bob Demeules, 559-1124 Tom Lufkin, 698-6523 ClarisWorks SIG m Apple II Novice SIG Macintosh Consultants SIG Southdale Library Ramsey County Library Byerly's 7100 York Avenue South, Edina II 2180 Hamline Ave. N., Roseville 3777 Park Center Blvd, St. Louis Park Denis Diekhoff, 920-2437 Tom Gates, 789-6981 Mike Carlson, 377-6553 Macintosh Main AppleWorks SIG Mac Programmers SIG St. Louis Park Library Ramsey County Library Van Cleve Park Bldg. 3240 Library Lane, St. Louis Park ffi. 2180 Hamline Avenue N., Roseville 15th Ave. SE & Como Ave.. Minneapolis "Tom Brandt Radius- "Desk Tools IV" Gervaise Kimm, 379-1836 Mike Carlson, 377-6553 Les Anderson, 735-3953 Photoshop SIG Digital Photography Jacor Southdale Library 1410 Energy Park Drive 7001 York Avenue South, Edina Suite 17, St.Paul "Marty Probst GIBBCO: Basic Principles Eric Jacobson, 645-6264 Denis Diekhoff, 920-2437 mini'apples The Minnesota Appie Computer Users' Group, Inc. -

English SCACOM Issue 3

English.SCACOM issue 3 (July 2008 ) Issue 3 www.scacom.de.vu July 2008 GGGGoooolllllldddd QQQQuuuueeeesssstttt 4444```` MMMMaaaakkkkiiiinnnngggg ooooffff NNNNyyyyaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaahhhh!!!! 11111111 !!!!nnnntttteeeerrrrvvvviiiieeeewwww wwwwiiiitttthhhh TTTThhhhoooorrrrsssstttteeeennnn SSSScccchhhhrrrreeeecccckkkk IIIInnnntttteeeerrrreeeessssttttiiiinnnngggg tttthhhhiiiinnnnggggssss BBBBeeeesssstttt rrrrCCCC66664444 GGGGaaaammmmeeeessss LLLLiiiisssstttt BBBBaaaarrrraaaaccccuuuuddddaaaassss ssssttttoooorrrryyyy aaa aaaaa aaaaaaa aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa Page - 1 -aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa aaaaaaa aaaaa aaa English.SCACOM issue 3 (July 2008 ) aaa aaaaa aaaaaaa aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa Page - 2 -aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa aaaaaaa aaaaa aaa English.SCACOM issue 3 (July 2008 ) Prologue . English SCACOM issue 3 with beautiful Imprint background pictures, interesting texts and a good game done by Richard Bayliss! English SCACOM is a free download- able PDF magazine.It’s scheduled every 3 months. First test of the new 1541U is included as well as the news from the last three month. There You can publish the magazine on your are a lot of interesting articles and the story of homepage without changes and link to www.scacom.de.vu only. the new game Gold Quest 4 with an Interview of the developer. Each author has Copyright of articles published in the magazine. Don’t use But it’s sad that there was very little feedback without permission of the author! for issue 2. Too nobody sent us texts or wants The best way to help would be if you to translate things. Due to this problems Eng- write some articles for us. lish.SCACOM is now scheduled every three Please send suggestions, corrections months. The next one will be released in Oc- or complaints via e-mail. tober 2008! Editoral staff: Please help us: write articles and give feed- Stefan Egger back. Write an E-mail to Joel Reisinger [email protected]. -

Download It Yourself

The world famous .... .... is now FREE 2 Commodore Scene 2004 am still awaiting news but I hope to have details very soon. CSDOOM64 : As yet nobody has taken up the challenge to produce this game. The cash is still Jeez, what a superb start to there and it will be increased throughout the year 2004 ! I dont really know where to encourage someone to take the plunge. There to begin so lets take things as has been lots of talk and speculation about how it they pop into my head. could be done but as yet, nobody wants the money ! CS2004 : I would like to Retro Gamer : Usually I would have just put a thank everybody who has re- mention in the Data Blast section about this subscribed for this year. I would magazine. However, the response to RG has been also like to thank those new subscribers for this huge, so much so that RG is not going to be a year - something I wasnt expecting to be honest. I quarterly magazine (as originally stated) but a bi- had three new subscribers in two days, thats not monthly publication. The page count has also been bad going in this day and age J increased and issue 2 has a huge article on Commo- I knew there would be lots of stuff to cram into dore written by Shaun Bebbington. I also feel that the begining of 2004 so I took Shauns advice and this is a golden oportunity to get something worth- did two issues together. I have also revamped CS while. -

SOFTDISK™ for Apple 11+ ®, Lie, Ilc, Ilc +, and IIGS

SOFTDISK™ for Apple 11+ ®, lIe, Ilc, Ilc +, and IIGS BACK ISSUE Catalog . A Word about Softdisk ... Jim Mangham established Softdisk in September 1981 by mail ing the first issue of Softdisk™to fifty Apple® owners. The first seventeen issues of Softdisk were single-disk issues, but since issue #18, all issues have been published on two disks. Issues since #81 are also available on single 3.5" disks. Today Soft disk in both formats is sent to thousands of eager Apple users each month. The SOFTDISK Back Issue Catalog allows you the opportunity to select only those issues which contain specific programs you would like to own - whether games or utilities, or tutorials or applications! The choice is yours! Back issue catalogs are also available for our other monthly col lections: Big Blue Disk™ for the IBM®-PC and compatibles, Loadstar™ for the Commodore 64/128®, and DiskWorld™ for the Macintosh~ If you would like one of these other back issue catalogs, you may request one when you call to place your order for Softdisk back issues. ORDER TODAV! CALL TOLL-FREE 1-lLlIIlIl.Jr'l..s-1LlII1IILlII "'£0::"'11'" Learnit - Memorize text the easy way with the help of your Apple. Dollar - A subroutine for formatting numerical values into dollars and cents output. - Print out numbers in whatever form you wish. - Print all text files on the earliest Softdisk issues. Ctlalnger - Edit DOS commands and error messages to read the way you like - View a track and sector map on your screen. - Select your program by number. Gr'ar:~hics - Learn how to use hi-res graphics.