Northumbria Research Link

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Future Day Orals PDF File 0.11 MB

Published: Tuesday 23 March 2021 Questions for oral answer on a future day (Future Day Orals) Questions for oral answer on a future day as of Tuesday 23 March 2021. The order of these questions may be varied in the published call lists. [R] Indicates that a relevant interest has been declared. Questions for Answer on Wednesday 24 March Oral Questions to the Minister for Women and Equalities Margaret Ferrier (Rutherglen and Hamilton West): What assessment she has made of the ability of same-sex couples to access insemination services in the UK. (913999) Mrs Sheryll Murray (South East Cornwall): What assessment she has made of the effect of the covid-19 outbreak on female employment. (914000) Julie Marson (Hertford and Stortford): What steps the Government is taking to promote the role of women during the UK’s G7 Presidency. (914001) Simon Fell (Barrow and Furness): What steps she is taking to ensure that good practice on making streets safer for women is shared. (914002) Ian Levy (Blyth Valley): What steps she is taking to promote female participation in STEM. (914004) Paul Howell (Sedgefield): What steps she is taking to promote female participation in STEM. (914005) Debbie Abrahams (Oldham East and Saddleworth): What steps the Government is taking to help protect disabled people from the effects of the covid-19 outbreak. (914006) Peter Aldous (Waveney): What steps she is taking to promote female participation in STEM. (914007) John Lamont (Berwickshire, Roxburgh and Selkirk): What steps she is taking to ban conversion therapy. (914008) 2 Tuesday 23 March 2021 QUESTIONS FOR ORAL ANSWER ON A FUTURE DAY Michael Fabricant (Lichfield): What steps she is taking to ban conversion therapy; and if she will make a statement. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Thursday Volume 642 14 June 2018 No. 153 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Thursday 14 June 2018 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2018 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 1053 14 JUNE 2018 1054 Sir Christopher Chope (Christchurch) (Con): Is not it House of Commons right that we in this country are not able to exercise some of the rights that people would wish us to exercise? Thursday 14 June 2018 The freedom to be able to transport live animals for slaughter is a freedom that we would prefer not to have. As soon as we leave the European Union, we will be The House met at half-past Nine o’clock able to take control of those things for ourselves. Mr Baker: My hon. Friend raises a point on which I PRAYERS am sure that many of us have received correspondence. I look forward to the day when it is within the powers of this House to change those rules. [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] Mr Stephen Hepburn (Jarrow) (Lab): Is not it right BUSINESS BEFORE QUESTIONS that we have a customs union that protects workers’ rights, with the right to allow state aid, the right to UNIVERSITY OF LONDON BILL [LORDS] allow public ownership, and the right to be able to ban Motion made, That the Bill be now read a Second outsourcing and competitive tendering should the time. Government wish to do so? Hon. Members: Object. Mr Baker: If you will allow me, Mr Speaker, I would like to pay tribute to the hon. -

Annual Review 2015

www.rfca-ne.org.uk We’re on Twitter – @NERFCA … and Facebook – @North-of-England-RFCA North East RCE FO S & E C V A VolunteerD R Annual Review E E S T E The Reserve Forces and Cadets Association S R A S D S N (RFCA) for the North of England O LEG VI VIC PF A C L IA G 2015 T N IO E N O F FO H R T H E N O RT Deeply happy Equipment grant plunges Make-over Cadets into diving / 38 for Navy training centre / 6 Saluting North East hospitals / 24 Stone for a hero / 9 News from Cadet Our region units / 30 and who we are / 39 2 North East Volunteer Inside this edition 5 10 12 16 20 27 33 Reserve Units ...............4-21 Employers ................ 22-29 Cadets ....................... 30-40 Cover picture: Cadets from Walker Technology College on the way to becoming qualified ocean divers, thanks to an equipment grant from the RFCA. 3 North of England RFCA Welcome elcome to this year’s edition of the North East Volunteer, our annual review of events W across the region and, as usual, it has been a busy twelve months for the Association as well as for our Reserves and Cadets. The structure of Reserves in our area continues to adjust under Future Reserves 2020 (FR20) with the planned relocation of some of our units and the consequent changes to the estate laydown. Recruiting for all Services is steadily improving. As the £2.8M Project Tyneside at HMS CALLIOPE nears completion it is already having a significant and positive impact on the Gateshead Quayside area. -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

INFLUENCERS on BREXIT Who Is Most Influential on Brexit?

INFLUENCERS ON BREXIT Who is most influential on Brexit? 1= 1= 3 4 5 Theresa MAY Angela MERKEL Nicola STURGEON Michel BARNIER Donald TUSK Chief Negotiator for the Prime Minister Federal Chancellor First Minister Commission Taskforce on Brexit President Negotiations UK Government German Government Scottish Government European Commission European Council 6 7 8 9 10 François HOLLANDE Philip HAMMOND David DAVIS Jean-Claude JUNCKER Guy VERHOFSTADT Secretary of State for Exiting the President Chancellor of the Exchequer President MEP & Lead rapporteur on Brexit European Union French Government UK Government UK Government European Commission European Parliament 11 12 13 14 15 Didier SEEUWS Enda KENNY Hilary BENN Mark RUTTE Martin SELMAYR Head of the General Secretariat of Chair, Committee on Exiting the Head of Cabinet of the President the Council Special Taskforce on Taoiseach European Union & Member of Prime Minister of the European Commission the UK Parliament, Labour Council of the EU Irish Government UK Parliament Dutch Government European Commission 16 17 18 19 20 Keir STARMER Donald TRUMP Wolfgang SCHÄUBLE Liam FOX Frans TIMMERMANS Secretary of State for Shadow Brexit Secretary US President-Elect Finance Minister First Vice-President Member of Parliament, Labour International Trade UK Parliament US Goverment German Government UK Government European Commission 21 22 23 24 25 Boris JOHNSON Nigel FARAGE Nick TIMOTHY Uwe CORSEPIUS Paul DACRE Joint Number 10 Special Adviser on Europe to Foreign Secretary MEP, Interim Leader of UKIP Chief-of-Staff, -

The Trolling of Gina Miller

The remoaner queen under attack: the trolling of Gina Miller What happens when a private individual takes on a very public cause? Amy Binns and John Mair examine how the case of Gina Miller demonstrates how fast social media can whip up a storm of abuse Gina Miller shot to fame after taking the British government to court for attempting to force through Article 50, the mechanism, which started the Brexit process. It was a case that, like the 2016 Referendum itself, polarised Britain. While Leavers were outraged that their vote to exit the EU was not the final word, Remainers watched with bated breath in hope that their disaster could turn to triumph. In the middle was the previously unknown financier Gina Miller. Articulate, photogenic and unafraid to comment on a controversial issue, she might have been made for the media. Widespread coverage led to her becoming a hate figure online, with two men arrested for making threats to kill her. In her own words, in her book Rise (Miller, 2018), she outlines the hate her campaign had generated: “Over the past two years I’ve been the target of extreme bullying and racist abuse. Ever since I took the UK government to court for attempting to force through Article 50, the mechanism for starting Brexit which would have led to the nation leaving the European union without Parliamentary consent, I live in fear of attacks. “I receive anonymous death threats almost every day. Strangers have informed me graphically that they want to gang rape me and slit the throats of my children, how the colour of my skin means I am nothing more than an ape, a whore, a piece of shit that deserves to be trodden into the gutter.” This study analyses 18,036 tweets, which include the username @thatginamiller, from October 1, 2016 to February 27, 2017, from just before the opening of her High Court case to beyond the Supreme Court ruling on January 26 . -

Wolfson Research Institute for Health and Wellbeing Here at Durham University

Wolfson Research Institute for Health and Wellbeing Annual Report 2019 Meet the Wolfson Team ................................................................................................ 4 Professor Amanda Ellison .......................................................................................... 4 Mrs Suzanne Boyd...................................................................................................... 4 Special Interest Groups .................................................................................................. 5 Teesside Aneurysm Group ......................................................................................... 5 Smoking Special Interest Group ................................................................................. 6 Pain SIG Report – Chronic pain: now and the future ................................................. 8 Physical Activity Special Interest Group .................................................................. 10 Stroke Special Interest Group .................................................................................. 13 Reports from Centres and Units .................................................................................. 14 Centre for the History of Medicine and Disease (CHMD) ........................................ 14 The Durham Infancy and Sleep Centre .................................................................... 15 Centre for Death and Life Studies ............................................................................ 17 Centre -

Stephen Kinnock MP Aberav

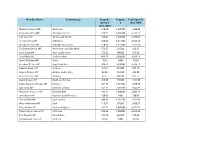

Member Name Constituency Bespoke Postage Total Spend £ Spend £ £ (Incl. VAT) (Incl. VAT) Stephen Kinnock MP Aberavon 318.43 1,220.00 1,538.43 Kirsty Blackman MP Aberdeen North 328.11 6,405.00 6,733.11 Neil Gray MP Airdrie and Shotts 436.97 1,670.00 2,106.97 Leo Docherty MP Aldershot 348.25 3,214.50 3,562.75 Wendy Morton MP Aldridge-Brownhills 220.33 1,535.00 1,755.33 Sir Graham Brady MP Altrincham and Sale West 173.37 225.00 398.37 Mark Tami MP Alyn and Deeside 176.28 700.00 876.28 Nigel Mills MP Amber Valley 489.19 3,050.00 3,539.19 Hywel Williams MP Arfon 18.84 0.00 18.84 Brendan O'Hara MP Argyll and Bute 834.12 5,930.00 6,764.12 Damian Green MP Ashford 32.18 525.00 557.18 Angela Rayner MP Ashton-under-Lyne 82.38 152.50 234.88 Victoria Prentis MP Banbury 67.17 805.00 872.17 David Duguid MP Banff and Buchan 279.65 915.00 1,194.65 Dame Margaret Hodge MP Barking 251.79 1,677.50 1,929.29 Dan Jarvis MP Barnsley Central 542.31 7,102.50 7,644.81 Stephanie Peacock MP Barnsley East 132.14 1,900.00 2,032.14 John Baron MP Basildon and Billericay 130.03 0.00 130.03 Maria Miller MP Basingstoke 209.83 1,187.50 1,397.33 Wera Hobhouse MP Bath 113.57 976.00 1,089.57 Tracy Brabin MP Batley and Spen 262.72 3,050.00 3,312.72 Marsha De Cordova MP Battersea 763.95 7,850.00 8,613.95 Bob Stewart MP Beckenham 157.19 562.50 719.69 Mohammad Yasin MP Bedford 43.34 0.00 43.34 Gavin Robinson MP Belfast East 0.00 0.00 0.00 Paul Maskey MP Belfast West 0.00 0.00 0.00 Neil Coyle MP Bermondsey and Old Southwark 1,114.18 7,622.50 8,736.68 John Lamont MP Berwickshire Roxburgh -

MAKING CHANGE HAPPEN! 7 – 9 September Kettering

MAKING CHANGE HAPPEN! 7 – 9 September Kettering ConferenCe ISSUe Hosted by Sandi Toksvig CONTENTS 04 Message from Women’s equality Party Leader 05 Welcome from Women’s equality Party Co-founders 07 Timetable at a glance FOUR PLAY AT 08 & 46 Making change happen 10-11 About the Women’s equality Party 12 About party conference CONFERENCE 13 Map of Kettering 14 - 15 Your guide to conference 16 - 17 Four Steps to taking part in Party Business 18 Kettering Conference Centre floor plan 22 Day 1: What’s on the agenda 23 - 29 Day 2: What’s on the agenda 30 - 31 Day 3: What’s on the agenda 34 Visitor experience Sophie Willan e velyn Mok Sophie Duker Ada Campe 35 Food Stalls Sophie Willan makes nominated for Female Sophie Duker describes Ada Campe’s act blends bold, unapologetic work Comedian of the Year herself as a “sexy- comedy, magic, regret 36 - 37 Exhibitors that is raucously funny and Show of the Year at cerebral comedy and shouting. A devotee and completely original. the 2017 Swedish Stand- underdog” and is quickly of variety and caba- 38 - 40 Who’s who: Women’s equality Party team Her work is political to Up gala, evelyn mok is establishing herself as ret, she has performed the core, but it doesn’t the best thing to come one of the most exciting throughout the UK for feel like it. out of Sweden since… new acts on the circuit. years. 41 - 45 Who’s who: Conference speakers @sophiewillan iKeA? @sophiedukebox @AdaCampe @evelynMok WOMEN’S EQUALITY 7:30pm PARTY COMEDY NIGHT Saturday 8 September 2 womensequality.org.uk Conference ISSUe 2 3 Welcome to the Women’s Equality Party’s second-ever party conference and to Kettering, a town famous according to its Conservative MP Philip Hollobone “as the home of Weetabix breakfast cereal”. -

Labour Party General Election 2017 Report Labour Party General Election 2017 Report

FOR THE MANY NOT THE FEW LABOUR PARTY GENERAL ELECTION 2017 REPORT LABOUR PARTY GENERAL ELECTION 2017 REPORT Page 7 Contents 1. Introduction from Jeremy Corbyn 07 2. General Election 2017: Results 11 3. General Election 2017: Labour’s message and campaign strategy 15 3.1 Campaign Strategy and Key Messages 16 3.2 Supporting the Ground Campaign 20 3.3 Campaigning with Women 21 3.4 Campaigning with Faith, Ethnic Minority Communities 22 3.5 Campaigning with Youth, First-time Voters and Students 23 3.6 Campaigning with Trade Unions and Affiliates 25 4. General Election 2017: the campaign 27 4.1 Manifesto and campaign documents 28 4.2 Leader’s Tour 30 4.3 Deputy Leader’s Tour 32 4.4 Party Election Broadcasts 34 4.5 Briefing and Information 36 4.6 Responding to Our Opponents 38 4.7 Press and Broadcasting 40 4.8 Digital 43 4.9 New Campaign Technology 46 4.10 Development and Fundraising 48 4.11 Nations and Regions Overview 49 4.12 Scotland 50 4.13 Wales 52 4.14 Regional Directors Reports 54 4.15 Events 64 4.16 Key Campaigners Unit 65 4.17 Endorsers 67 4.18 Constitutional and Legal services 68 5. Labour candidates 69 General Election 2017 Report Page 9 1. INTRODUCTION 2017 General Election Report Page 10 1. INTRODUCTION Foreword I’d like to thank all the candidates, party members, trade unions and supporters who worked so hard to achieve the result we did. The Conservatives called the snap election in order to increase their mandate. -

The Anti-Britain Campaign the Brexit Legal Challenge (2016)

11th February 2018 The Anti-Britain Campaign Typical of the "Doublespeak" from the Left and its allies is the campaign set-up by Gina Miller "Best for Britain" which is clearly a pro-EU campaign which seeks to prevent Britain leaving the EU and keep us trapped within the protectionist bloc. Despite the fact that Miller has moved away from the "Best for Britain" campaign group that she established, she is still, nevertheless, acting along the same principles of that campaign - calling for a second Referendum which would offer alternatives such as accept or reject anything that the government agrees with Brussels or alternatively simply remain in the EU. In an Evening Standard interview in 4th November 2016 (Brexit legal challenge: Gina Miller argues 'defending democracy is the best way to spend my money') Miller stated that those who voted (in a record breaking voter turnout) on the 23rd June 2016 EU Referendum vote "... believed whatever way they voted they were doing the best for their families, but the politicians misled the public into believing whatever the outcome of the advisory referendum was would be made law, knowing well that would not be the case. That unleashes anger.” That statement, some 4 months after the EU Referendum vote, is particularly revealing for two reasons (1) it shows that she was knew that the government would not implement the Referendum vote result and (2) that she considered the Referendum to be only "advisory" - along with the rest of the British establishment - Politicians, Peers, Civil Servants and Judiciary. The second part of the statement is at odds with the idea that she now supports a second Referendum vote, unless that is also only advisory, and the first part - it simply supports the idea that her campaigning is really about assisting the establishment to thwart the original Referendum vote. -

MILLER GINA Founder of True and Fair Foundation Anti-Brexit Activist

PATH OF EXCELLENCE PARCOURS D’EXCELLENCE MILLER GINA MILLER GINA Fondatrice de True and Fair Foundation Founder of True and Fair Foundation Anti-Brexit Activist M Militante anti-Brexit M United Kingdom Royaume-Uni Gina MILLER was born in 1965 to British Guyanese Gina MILLER est née en 1965 de parents guyanais. Elle parents. She joined England to study law at the University rejoint l’Angleterre pour y poursuivre des études en droit of East London and managed to finance them by modeling. à l’Université de Londres-Est et parvient à les financer en Upon her parents’ request, she returned to Guyana without faisant du mannequinat. Sur injonction de ses parents, elle having been able to validate her training. She then obtained retourne en Guyane sans avoir pu valider sa formation. a degree in Marketing, as well as a Master’s degree in Human Elle obtient ensuite un diplôme en marketing, ainsi qu’une Resources Management from the University of London. maîtrise en gestion des ressources humaines à l’Université In 1987, the daughter of the Attorney General of Guyana de Londres. En 1987, la fille du procureur général de la owned a photographic laboratory. She joined the BMW Guyane est propriétaire d’un laboratoire photographique. © CRÉDIT PHOTO teams in 1990 as marketing and events manager. After two © CRÉDIT PHOTO Elle rejoint les équipes de BMW en 1990 en qualité de years of activity, she started her own business by creating a 2017 : responsable marketing et événementiel. Après deux ans marketing agency. In 2009, Gina co-founded the True and Elle lève 420 000 d’activité, elle se met à son compte en créant une agence Fair Foundation with her husband.