Singapore's Report on Health Services

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enhancing the Competitiveness of the Health Services Sector in Singapore

CHAPTER 3 Transforming the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) into a Global Services Hub: Enhancing the Competitiveness of the Health Services Sector in Singapore KAI HONG PHUA Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore NICOLA S POCOCK Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore 1. Introduction Singapore was the first country in the region to officially articulate an aim to attract medical tourists and promote the export of health services overseas. In 2003, the Healthcare Services Working Group (HSWG) of the Economic Review Committee recommended that Singapore attract one million foreign patients by 2012. To achieve this goal, the Singapore Tourism Board (STB), along with the Economic Development Board (EDB) and International Enterprise (IE) Singapore, launched SingaporeMedicine in 2003, a multi-agency initiative that aims to promote, develop and maintain Singapore as an international medical hub. However, in recent years, the push for medical tourism has been muted. Sectiononeof this paper summarizes the Singapore context for a past medical tourism hub policy, followed by an overview of the health system, with policy implications for the system should medical tourism become a major growth area. Methodology is then described in section two, followed by the findings of the SWOT analysis conducted among stakeholders in the health services sector. 111 The objective of this paper is to: 1. Undertake a SWOT analysis for the health services sector in Singapore. 2. Undertake an analysis of policies/regulatory/institutional support for the health services sector in Singapore. 3. Develop a profiling of firms which are considered key players for the health services industry. -

Healthcare List of Medical Institutions Participating in Medishield Life Scheme Last Updated on 1 April 2020 by Central Provident Fund Board

1 Healthcare List of Medical Institutions Participating in MediShield Life Scheme Last updated on 1 April 2020 by Central Provident Fund Board PUBLIC HOSPITALS/MEDICAL CLINICS Alexandra Hospital Admiralty Medical Centre Changi General Hospital Institute of Mental Health Jurong Medical Centre Khoo Teck Puat Hospital KK Women's And Children's Hospital National Cancer Centre National Dental Centre National Heart Centre Singapore National Skin Centre National University Hospital Ng Teng Fong General Hospital Singapore General Hospital Singapore National Eye Centre Sengkang General Health (Hospital) Tan Tock Seng Hospital PRIVATE HOSPITALS/MEDICAL CLINICS Concord International Hospital Farrer Park Hospital Gleneagles Hospital Mt Alvernia Hospital Mt Elizabeth Hospital Mount Elizabeth Novena Hospital Parkway East Hospital Raffles Hospital Pte Ltd Thomson Medical Centre DAY SURGERY CENTRES A Clinic For Women A Company For Women A L Lim Clinic For Women Pte Ltd Abraham’s Ear, Nose & Throat Surgery Pte Ltd Access Medical (Bedok South) Access Medical (Bukit Batok) Access Medical (Circuit Road) Access Medical (East Coast) Access Medical (Jurong West) Access Medical (Kim Keat) Access Medical (Marine Terrace) Access Medical (Redhill Close) Access Medical (Tampines 730) Access Medical (Toa Payoh) Access Medical (Whampoa) 2 Access Medical (Teck Ghee) Adult & Child Eye (ACE) Clinic Advance Surgical Group Advanced Centre For Reproductive Medicine Pte. Ltd. Advanced Medicine Imaging Advanced Urology (Parkway East Medical Center) Agape Women’s Specialists -

Industrial Sponsorships

Introduction to Industrial Sponsorships Candidates who have the passion to become healthcare professionals and would like to seek financial sponsorship in the healthcare sector may approach the following organisations to discuss their interest in joining the sector. Please note that any sponsorship awarded may typically come with obligations to serve a working bond with the sponsoring organisation. Parkway Pantai Student Scholarship [Radiology] Parkway Pantai is one of Asia’s largest integrated private healthcare groups operating in Singapore, Malaysia, India, China, Brunei and United Arab Emirates. For over 40 years, its Mount Elizabeth, Gleneagles, Pantai and Parkway brands have established themselves as the region’s best known brands in private healthcare, synonymous with best-in-class patient experience and outcomes. It is part of IHH Healthcare, the world’s second largest healthcare group by market capitalisation. IHH operates more than 10,000 licensed beds across 50 hospitals in 10 countries worldwide. In Singapore, Parkway Pantai is the largest private healthcare operator with four JCI- accredited, multi-specialty tertiary hospitals - Mount Elizabeth Hospital, Mount Elizabeth Novena Hospital, Gleneagles Hospital and Parkway East Hospital. It also owns Parkway Shenton, a large network of primary healthcare clinics and services, ParkwayHealth Radiology, ParkwayHealth Laboratory and Parkway College. Types of Sponsorships: Partial / Full Sponsorships Bond Duration: 3 years upon graduation / 6 years upon graduation Contact Person: Linus Leow Email Address: [email protected] Website: https://www.parkwayhospitals.com/ Industrial Sponsorships by other Healthcare Institutions The following organisations have also sponsored candidates in the past and may offer sponsorships for accepted candidates of this programme. You may wish to visit the organisations’ websites for more details or contact the relevant person in the respective organisation by phone or in writing to find out the selection procedures. -

Singapore Hospitals Room Charges

ROOM CHARGES DAILY RATE (S$) NO HOSPITAL WARD TYPE & DESCRIPTION ASUMSI RATE Rp.9.500/S$ INCLUDES 7% GST 1 SINGAPORE GENERAL HOSPITAL Standard Ward Class C (9-bedded room) From S$ 35 per day Rp 332,500 Standard Ward Class B2 (6-bedded room) From S$ 70 per day Rp 665,000 Standard Ward Class B2+ (air conditioned 5-bedded From S$ 140 per day Rp 1,330,000 room) Standard Ward Class B1 (air conditioned 4-bedded From S$ 226.84 per day Rp 2,154,980 room) Standard Ward Class A1+/A1 (single room) From S$ 422.65 / 396.97 per day Rp. 4,015,175 / Rp. 3,771,215 2 ALEXANDRA HOSPITAL Class A (Single bedroom) S$ 336 per day Rp 3,192,000 Class B1 (4-bed room) S$ 235 per day Rp 2,232,500 Class B2 (6-bed room) S$ 219 per day Rp 2,080,500 Class C (Open ward) S$ 187 per day Rp 1,776,500 3 CHANGI GENERAL HOSPITAL Class A (Single bedroom) From S$ 390 per day Rp 3,705,000 Class B1 (4-bed room) From S$ 289 per day Rp 2,745,500 Class B2 (6-bed room) From S$ 249 per day Rp 2,365,500 Class C (Open ward) From S$ 205 per day Rp 1,947,500 4 GLENEAGLES HOSPITAL Gleneagles Suite S$ 6,677 Rp 63,431,500 Tanglin Suite S$ 5,361 Rp 50,929,500 Napier / Nassim Suite S$ 2,729 Rp 25,925,500 Dalvey Suite S$ 1,314 Rp 12,483,000 Executive Deluxe Suite S$ 1,314 Rp 12,483,000 Executive Suite S$ 1,095 Rp 10,402,500 Superior Room S$ 766 Rp 7,277,000 Single Room S$ 585 Rp 5,557,500 Two-Bedded S$ 321 Rp 3,049,500 Four Bedded S$ 239 Rp 2,270,500 KK WOMAN'S & CHILDREN'S 5 Rooms - A1 (Single) From S$ 395.90 per day Rp 3,761,050 HOSPITAL Rooms - B1 (4-Beds) From S$ 224.70 per day Rp 2,134,650 -

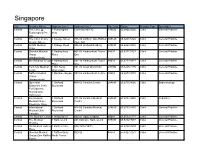

List of Medical Providers for Direct Billing Facilities in Singapore

LIST OF MEDICAL PROVIDERS FOR DIRECT BILLING FACILITIES IN SINGAPORE INPATIENT SERVICES (Note: Prior approval is required) Name of Hospital Address I. Gleneagles Hospital 6A Napier Road, Singapore 258500 II. Mount Elizabeth Hospital 3 Mount Elizabeth, Singapore 228510 III. Mount Elizabeth Novena Hospital 38 Irrawaddy Road, Singapore 329563 II. Mount Elizabeth Hospital 3 Mount Elizabeth, Singapore 228510 IV. Parkway East Hospital 321 Joo Chiat Place, Singapore 427990 V. Raffles Hospital 585 North Bridge Road, Raffles Hospital #11-00, Singapore 188770 OUTPATIENT SERVICES Name of Clinic Address I. Group of Raffles Medical Clinics Please visit the following website to download the latest clinic location listing of Raffles Medical Clinics: http://www.rafflesmedicalgroup.com/family-medicine/clinic-location- listing II. Parkway Shenton Group Clinics (for clinic schedule, please visit: http://www.parkwayshenton.com) 1) Alexandra Retail Centre - Shenton Wellness Centre 460 Alexandra Road, #02-15 PSA Building (Alexandra Retail Centre), Singapore 119963 2) Buangkok MRT - Shenton Medical Group 10 Sengkang Central, #01-04 Buangkok NEL MRT Station, Singapore 545061 3) Bukit Panjang Plaza - Shenton Medical Group No.1 Jelebu Road, #03-02 Bukit Panjang Plaza, Singapore 677743 4) Clementi Central - Shenton Family Medical Clinic Blk 451 Clementi Avenue 3, #01-309, Singapore 120451 5) Dhoby Xchange - Shenton Medical Group 11 Orchard Road, #B2-01 Dhoby Ghaut MRT Station, Singapore 238826 6) Esplanade Xchange - Shenton Medical Group 90 Bras Basah Road, #B1-02 -

Sparking Innovation Parkway Pantai Innovation Challenge 2019 Brings Fresh Ideas to Elevate the Healthcare Experience

mosaic APR - JUN 2019 APR JUN mosaic 2019 BETTER HEALTHY LIVING SERVING THROUGH WELL-BEING IN BRUNEI THE YEARS New mental health service In partnership with Celebrating staff loyalty at Gleneagles Hong Kong Brunei’s Ministry of Health at Singapore Operations Sparking Innovation Embracing innovation and digitalisation positions Parkway Pantai in good stead for the future. New Service Models Clinical Operational Enhancement Efficiency Service Excellence A Parkway Pantai Publication Editor’S NOTE NEW FRONTIERS OF HEALTHCARE Digital health and innovation come into focus as Parkway Pantai gears up for the future. he technological revolution has given rise to the age of innovation and Parkway Pantai is fully embracing the paradigm shift. Continuing its push to cultivate ingenuity from within, Parkway Pantai Innovation Challenge 2019 was held for the Tsecond year from January to May, drawing record high participation by 250 teams comprising more than 700 staff from six countries. Read about the winning projects and teams in this issue of Mosaic (Page 8 - 11). Over in Singapore, digital health is shaping healthcare delivery with doctors and patients enjoying greater convenience from the recently launched Parkway DigiCare and DigiHealth mobile apps (Page 12). More enhancement features will be progressively released, as Parkway Pantai leverages technology and big data to stay relevant in today’s increasingly digitised world. Across our markets, our people continue to make a difference to the lives of our patients and the community. Our Gleneagles Jerudong Park Medical Centre in Brunei launched two initiatives to promote healthy living and develop healthy lifestyle programmes for Brunei’s government ministries (Page 19). -

Your Guide to Quality Medical Care in Singapore Photo Credits: Raffles Medical Group Contents

your guide to quality medical care in singapore Photo credits: Raffles Medical Group contents 01. AsiA’s leAdinG MedicAl hub 2 02. singapoRe’s heAlthcARe 3 systeM 03. ACCREDITATIONS And 5 ACCOLADES 04. medicAl fiRsts 6 05. ouR heAlthcARe 8 professionAls sPeAk 06. HeAR fRoM ouR patients 10 07. SingapoRe: MoRe thAn just 12 a heAlthcARe destinAtion 08. heAlthcARe provideRs 13 1 01 AsiA’s leAdinG MedicAl hub behind its dynamic and multi-cultural professionals and multi-national healthcare- landscape, singapore is often associated related companies from various parts of the with excellence, efficiency and effectiveness, world to share and exchange their expertise, from its airport, airline and port to its conduct healthcare-related research and infrastructure, education and healthcare training, as well as to host international systems. singapore has become a trusted conferences and events. healthcare name among international patients. it is providers in singapore are constantly also recognised as Asia’s leading medical strengthening their medical capabilities hub providing internationally accredited through professional exchanges and access and patient-centric care. to innovation in medical technology through our robust healthcare eco-system. international patients come to singapore for a wide range of medical care, ranging in singapore, medical travellers can from basic health screenings to advanced receive quality medical care in an procedures in fields such as cardiology, environment that is safe and welcoming, neurology, oncology, ophthalmology, organ with no uncertainties of wars, political transplants, orthopaedics and paediatrics. instability, social unrest, natural disasters or worries about blood safety. here, medical As a multi-faceted medical hub, singapore travellers can enjoy a peace of mind when attracts a growing number of medical health really matters. -

Direct Settlement Network Report

Singapore City Provider Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Zip Code Phone Provider Type Specialties Central The Clinic @ 1 Fusionopolis Connexis #03-10 138632 65.6466.0602 Clinic General Practice Fusionopolis Pte Way Ltd Central The Clinic at One 1 George Street #05-05 Lobby C One Raffles 049145 65.6438.5322 Clinic General Practice George Street Place Mrt Central ACMS Medical 1 Grange Road #06-06 Orchard Building 239693 65.6262.5052 Clinic General Practice Clinic Central Shenton Medical 1 Harbourfront #01-04 Harbourfront Tower 98633 65.6377.5727 Clinic General Practice Group Place One (Harbourfront) Central Mint Medical Group 1 Harbourfront #01-10 Harbourfront Tower 98633 65.6272.9372 Clinic General Practice Place One Central Twin City Medical 1 Kim Seng #01-32 Great World City 237994 65.6235.1175 Clinic General Practice Centre Promenade Central Raffles Medical 1 Maritime Square #03-56 Harbourfront Centre 99253 65.6273.3078 Clinic General Practice Clinics (Harbourfront) Central Specialist 1 Orchard #04-03 Camden Centre 248649 65.6735.4066 Clinic Endocrinology Endocrine Clinic Boulevard For Diabetes, Thyroid And Hormones Central International 1 Orchard #11-06 Camden Medical 248649 65.6887.4440 Clinic Pediatrics Medical Clinic - Boulevard Centre Paediatric Clinic Central International 1 Orchard #14-06 Camden Medical 248649 65.6733.4440 Clinic General Practice Medical Clinic Boulevard Centre Camden Central The Bonham Clinic 1 Phillip Street #04-02 Lippo Building 48692 65.6533.1177 Clinic General Practice Central The Medical 1 Raffles Link -

VUMI 1 Henner List of Medical Providers Asia & P Acific

1 of 112 Asia & Pacific EFFECTIVE 2020 AFGHANISTAN Provider Type Provider Name City Hospitals & Clinics New Kaisha Herat Herat Hospitals & Clinics Amiri Medical Complex Kabul Hospitals & Clinics Blossom Group Kabul Hospitals & Clinics Global Curative Hospital Kabul Hospitals & Clinics Gulf Healthcare Hospital Kabul Hospitals & Clinics Kaisha Health Care Indo Afghan Hospital Kabul Hospitals & Clinics Kamal Orthopedic Hospital Kabul Hospitals & Clinics Matab Healthcare Kabul Hospitals & Clinics Westex Medical Solutions Kabul VUMI 1 Henner List of Medical Providers Hospitals & Clinics Kaisha Farabi Health Care Mazar-e-sharif Independent Physicians Eutelmed Kabul Medical Centers DK-German Medical Diagnostic Center Ltd. Kabul AUSTRALIA Provider Type Provider Name City Check-up Centers The Travel Doctor - Adelaide Adelaide Check-up Centers The Travel Doctor -Brisbane Brisbane Check-up Centers The Travel Doctor - Canberra Canberra Check-up Centers Epworth Healthcheck Melbourne Check-up Centers The Travel Doctor - Melbourne Melbourne Check-up Centers The Travel Doctor - TMVC Perth Perth Check-up Centers Executive Health Solutions Sydney Check-up Centers The Travel Doctor - Sydney Sydney Hospitals & Clinics Dr Deb The Travel Doctor Brisbane Hospitals & Clinics Mater Mothers’ Private Hospital Brisbane Hospitals & Clinics The Wesley Hospital Brisbane Hospitals & Clinics Hollywood Private Hospital Nedlands Hospitals & Clinics Royal North Shore Hospital Newcastle Hospitals & Clinics Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital Perth Hospitals & Clinics Dr Robyn -

STUDENT HANDBOOK (Year 2011)

CHARTERED INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY STUDENT HANDBOOK (Year 2011) 450 Telok Blangah Street 31, Singapore 108943 Tel: 65-6276 4890 Fax: 65-6276 5901 www.citech.edu.sg TABLE OF CONTENTS NO. CONTENTS PAGE NO. 1. STUDENT HANDBOOK 3 2. HOW TO CONTACT US 4 3. ABOUT CHARTERED INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY (CITECH) 7 4. CONDITIONS OF ADMISSIONS 9 5. FEE PROTECTION SCHEME 11 6. FINANCIAL MATTERS 12 7. COURSE REFUND, TRANSFER/ WITHDRAWAL 15 8. DISPUTE RESOLUTION POLICY AND PROCEDURE 22 9. LIST OF STUDENTS SERVICES AVAILABLE 27 10. ORIENTATION PROGRAM 29 11. GENERAL ADMINISTRATION INFORMATION 30 12. YOUR RESPONSIBILITIES AS A STUDENT 31 13. CODE OF CONDUCT 32 14. FEEDBACK FROM STUDENTS 36 15. ACADEMIC INFORMATION 37 16. EXAMINATION PROCEDURES 40 17. TEACHING AND LEARNING METHODS 45 18. ASSESSMENTS 46 19. REFERENCING METHODS 49 20. INFORMATION SKILLS GUIDE 55 21. LIVING IN SINGAPORE 57 Student Handbook - CITECH October 2011 Page - 2 (Copyright Reserved. Property of CITECH) 1. STUDENT HANDBOOK Welcome to Chartered Institute of Technology! At CITECH, we believe there is no ending to an individual’s learning curve. That is where CITECH comes in as an important learning cycle for all be it you are young or elderly. The school aims to be student focused and provide the best work-ready education and graduates through its programmes, services and learning environment. Classes are generally small to create a supportive learning environment where plenty of “hands-on” experience is possible. Our academic staffs have appropriate qualifications and experience in their areas of expertise so that you can get the best possible teaching support for your learning. -

General Hospital (CGH) • Collaboration Is Part of CGH's Contingency Plan to Manage Potential Surge Situations

MEDIA RELEASE CHANGI GENERAL HOSPITAL PARTNERS WITH GLENEAGLES HOSPITAL TO ADMIT DENGUE PATIENTS • Gleneagles Hospital (GEH) will set aside up to 12 beds for dengue patients coming from Changi General Hospital (CGH) • Collaboration is part of CGH's contingency plan to manage potential surge situations Singapore, 22 July 2013 - As part of efforts to better care for an expected increase in demand from dengue patients, Changi General Hospital (CGH) and Gleneagles Hospital (GEH) have embarked on an initiative which taps on private sector bed capacity in the care of such patients. The collaboration will allow private acute hospitals to play a role in supporting the health-care needs of subsidized patients in Singapore. CGH patients warded at GEH will continue to retain their subsidy status and be cared for by the team of infectious disease specialists and nurses at GEH. 2 "We are piloting the initiative with GEH so that our hospital would be able to leverage on its capacity and resources should we see a surge in dengue patients, especially during the hotter months of August and September,” said Dr Lee Chien Earn, CEO of Changi General Hospital. 3 "This collaboration shows how the private and public sectors can come together to serve the healthcare needs of Singaporeans," said Dr Tan See Leng, Group Chief Executive Officer and Managing Director of Parkway Pantai Limited, which manages Gleneagles and three other private hospitals in Singapore. "We are happy to be able to play our part during this time of need and will offer our resources again when necessary, in the future." 4 The CGH-Gleneagles collaboration is expected to last between three to six months. -

Affordable Excellence: the Singapore Healthcare Story

HASE LTIN This is the story of the Singapore healthcare system: how it works, how it is financed, its history, where it is going, and E what lessons it may hold for national health systems around the world. Singapore ranks sixth in the world in healthcare out- AFFORDABLE comes, yet spends proportionally less on healthcare than any other high-income country. This is the first book to set out a comprehensive system-level description of healthcare in Singapore, with a view to understanding what can be learned from its unique system design and development path. EXC ELLE The lessons from Singapore will be of interest to those currently Affordable planning the future of healthcare in emerging economies, as NC E: THE SINGAPORE HEA E: THE SINGAPORE Excellence well as those engaged in the urgent debates on healthcare in The Singapore Healthcare Story the wealthier countries faced with serious long-term challenges in healthcare financing. Policymakers, legislators, public health by William A. Haseltine officials responsible for healthcare systems planning, finance and operations, as well as those working on healthcare issues in universities and think tanks should understand how the Singa- pore system works to achieve affordable excellence. WILLIAM A. HASELTINE is President and Founder of LT HCARE S ACCESS Health International dedicated to promoting access to high-quality affordable healthcare worldwide, and is President of the William A. Haseltine Foundation for Medical Sciences TORY and the Arts. He was a Professor at Harvard Medical School and was the Founder and CEO of Human Genome Sciences. BROOKINGS Brookings Institution Press Washington, D.C.