Action-Front.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

W.L. Baillieu in the Archives

UMA Bulletin NEWS FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE ARCHIVES www. lib.unimelb.edu.au/collections/archives No. 24, December 2008 Searching for a Forgotten Life W.L. Baillieu in the Archives opular perception is a strange and At the same time he took over the fickle thing. I recently wrote a stricken stockbroking firm of W.J. Malpas Phistory of Australia’s Collins Class & Co. and built up a stockbroking busi- submarines. I began that project sharing ness with his brothers Edward (Prince), the almost universal belief that these Clive (Joe), Norman and Maurice (Jac), submarines are ‘noisy as a rock concert’ which as E.L. & C. Baillieu has been one — I was rather surprised to find out that of the leading stockbrokers in Melbourne they are, in fact, the second quietest for over 100 years. Throughout his busi- submarines in the world. ness life WL worked closely with five of Since I have begun working on a his brothers and, while he was always biography of W.L. Baillieu I have discov- acknowledged as the leader, their business ered that, while the Baillieu family is well success was very much a joint effort. W.L. Baillieu, 1911. known, for most people WL (as he was W.L. Baillieu played a large part in a universally known) is remembered solely dramatic resurgence of Victorian gold- alliance of companies, of which WL was as a landboomer who paid sixpence in the mining in the 1890s, promoting, man- the unofficial but unquestioned leader. pound on his debts when the land boom aging and raising capital for several of the The group was named for Collins House collapsed in the early 1890s. -

Chapter 4 of Well Rowed University: Melbourne University Boat Club

Well Rowed University melbourne university boat club the first 150 years The front page and accompanying note to the reconstructed records of the Club 1859–70, completed by John Lang in July 1912 Judith Buckrich MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY BOAT CLUB INC . The Club was soon enjoying the pleasures of peacetime rowing. In 1919 it celebrated its diamond jubilee year. A subcommittee was established to investigate extensions for the boatshed and funds were sought. Plans got underway to revive the intervarsity and intercollegiate races, the latter now including Newman College. To facilitate four crews racing in the intercollegiate race (Trinity, Ormond, Queen’s, Newman) it was necessary to chapter four have two heats with the winners racing off in a fi nal. For the 1919 college boat race, heats were rowed on 9 May with the fi nal taking place the next day. In addition to being the fi rst intercollegiate race in which Newman would participate, this race would be the fi rst where the newly instituted Mervyn Bournes Higgins Trophy was competed for. Ormond College beat Queen’s while Newman was too good for Trinity. In the fi nal, Ormond won Between the Wars the Mervyn Bournes Higgins trophy for the fi rst time by defeating Newman by two lengths in a spirited race.1 The fi rst postwar intervarsity race was held on the Parramatta River on Saturday, 31 August 1919. Adelaide and Queensland Universities found it impossible to send crews so soon after the War, so only Sydney and Melbourne competed: ‘The weather was spring like with a slight breeze from the S. -

Chapter 5 of Well Rowed University: Melbourne University Boat Club

Well Rowed University melbourne university boat club the first 150 years The front page and accompanying note to the reconstructed records of the Club 1859–70, completed by John Lang in July 1912 Judith Buckrich MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY BOAT CLUB INC . w e l l r o w e d u n i v e r s i t y From June 1940, when the German war machine struck, and Europe rapidly fell to the German blitzkrieg of ‘lightning war’, Australia was increasingly involved in the confl ict. The Club was deeply affected. Many students were enlisting and Melbourne itself was soon enveloped in blackouts and brownouts. Weekday sporting events were restricted by Commonwealth Government controls. At the annual meeting of 7 August 1940 Lex Rentoul, who had been appointed to the RAAF, retired as president but remained Vice- chapter five President temporarily. The new President, Hubert T Frederico, moved that a letter of appreciation be sent to Rentoul for his ‘magnifi cent work’. The meeting ‘emphasised Mr Rentoul’s complete devotion to the Club’s interests over a considerable number of years, when his time, energy, and enthusiasm not only resulted in a higher standard of rowing, but succeeded in eliminating the factions that had been visible previously inside Another war, another peace the Club.’1 He and Dr Hugh Murray, whose services were also acknowledged, were made honorary life members of the Club. Other Vice-Presidents elected were DRM Cameron, HAK Hunt, Dr Murray, Mr 1940–1965 Whitney King and LH Wilson. GH Gossip was voted Captain and Mr Craig, Vice-Captain. -

Strathfieldsaye Estate

HISTORY OF THE STRATHFIELDSAYE ESTATE By Maurice Pawsey H ISTORIC S TRUCTURE S ERIES GIPPSLAND STRATHFIELDSAYE ESTATE © BY MAURICE PAWSEY Photograph Contributors: Maurie Pawsey Early Photographer Contributions: From Australian Pictures - Howard Willoughby 1886 Others: From Strathfieldsaye - A History & Guide by Meredith Fletcher 1992 Centre for Gippsland Studies INTRODUCTON I became involved with Strathfieldsaye Estate through my position as Head of the Property & Buildings Department in the Administration of the University of Melbourne, as described in Chapter 8. At that time 1977, Strathfieldsaye Homestead was known as the oldest, continuously occupied Homestead in Gippsland. I do not believe the University`s occupation of the property and that of the Australian Landscape Trust has changed that situation. It is a fascinating property, particularly in that when taken over by the University it reflected the over 100 years of occupation by one pioneer- ing family, with all the furniture, pictures and bric-a-brac of a family. It is situated on the north-east shore of Lake Wellington, the most west- erly of the Gippsland Lakes. Sale is situated on the western side of the Lake and Stratford –to the north, is the nearest town to Strathfieldsaye. So we have a Homestead, commenced around 1850, replacing early sheds on the site, extended mainly by the Disher family and occupied by successive generations of that family until the last surviving mem- ber donated it to the University in 1977. This Essay gives the history of the property, the University`s -

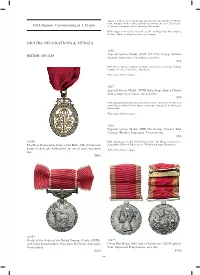

Fifth Session, Commencing at 2.30 Pm ORDERS, DECORATIONS

Together with case (this with foxing) and also letter date 5th June 1959 from Prime Minister's Offi ce at Whitehall to Miss J.M.Owens, The Coffer House, Fifth Session, Commencing at 2.30 pm Newtown, Montgomeryshire, advising of the award. BEM: Supplement to LG 8/6/1950, p2803, to Miss Jessie May Owens, Member, Women's Voluntary Services, Newtown. ORDERS, DECORATIONS & MEDALS 1036 Imperial Service Medal, (GVR 1931-37). George William BRITISH SINGLES Penman. Impressed. No ribbon, very fi ne. $50 ISM: LG 15/12/1931, p8064, for Home Civil Service to George William Penman, Overseer, Post Offi ce, Manchester. With copy of Gazette pages. 1037 Imperial Service Medal, (GVIR Indiae Imp). Sidney Charles Pursey. Impressed. Good extremely fi ne. $50 ISM: Second Supplement to LG 22/6/1948, p3696 - for Home Civil Service, Admiralty, to Sidney Charles Pursey, storehouse assistant, H.M.Dockyard, Portsmouth. With copy of Gazette pages. 1038 Imperial Service Medal, (EIIR Dei Gratia). Edward John Clarence Wackley. Impressed. Extremely fi ne. $50 1034* ISM: Supplement to LG 30/5/1961, p3980 - for Home Civil Service, The Most Honourable Order of the Bath, (CB) (Civil), neck Admiralty, to Edward John Clarence Wackley, machinist, Devonport. badge in silver gilt, hallmarked. In case of issue, extremely With copy of Gazette pages. fi ne. $400 1035* Medal of the Order of the British Empire, (Civil), (GVIR), 1039* with ladies brooch ribbon. Miss Jessie M.Owens. Impressed. China War Medal 1842. James Grahme (sic) 26th Regiment Uncirculated. Foot. Impressed. Edge knocks, very fi ne. $250 $750 99 \ 1040* Indian Mutiny Medal 1857-58, - clasp - Central India, with brooch bar suspender and this engraved, 'Watch And/Be Sober'. -

Chapter 3 of Well Rowed University: Melbourne University Boat Club

Well Rowed University melbourne university boat club the first 150 years The front page and accompanying note to the reconstructed records of the Club 1859–70, completed by John Lang in July 1912 Judith Buckrich MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY BOAT CLUB INC . w e l l r o w e d u n i v e r s i t y University elite become leaders of the Club The committee bought a large blue and black diagonal striped fl ag, with MUBC in white lettering on it, and this was unfurled by the Lieutenant Governor, Sir John Madden, at the Club sheds on 30 March 1904. According to John Lang, this was the fi rst fl ag of this design ever fl own by a university club. The fl ag went missing and was thought (by John Lang) to have been stolen around Henley Regatta Day in 1910. Mysteriously, an unknown person left a brand new fl ag of exactly the same design at Lang’s offi ce on 12 chapter three August 1911.1 In the Club’s records Lang mused, ‘Was it conscience or a generous but anonymous donor?’. To his great surprise, the old fl ag was discovered in 1911, having been inadvertently rolled up with other Henley paraphernalia. To his even greater surprise, he then discovered the anonymous donor was none other than his wife, who was ‘induced The fabulous years until the to confess the gift owing to my telling her how the old fl ag had been found.’2 Sadly, there is no trace of either fl ag today. -

The John Hall Rowing Scholarship

MUBC MAY NEWSLETTER 2019 MUBC Committee Welcome to the May 2019 Issue of Elected October 2018 the MUBC Newsletter. Quite a lot has happened since our last Newsletter, so President Christian Ryan this is a bumper edition. It is the Club’s Vice President Minnie Cade plan to be able in the future to update Treasurer Chris Hargreaves you on the various doings at MUBC Secretary Greg Longden Captain Gary Butcher on an approximately quarterly basis. Vice Captain Sarah Ben-David Ordinary member Sandy Marshall Ordinary Member Edward Walmsley New Coaching and Admin Staff Ordinary Member Milla Marston Rowing seems to invite change and this last year has been no exception. Matt Ryan High Performance Coach Part Time Olympic Silver Medalist 2008 James Smith Women’s Development Full Time NSW Coach of the Year 2015 and Club Coach Michael Poulter Men’s Development Coach Part Time U23 World Championships 2013 Ben Board MUBC Academy Manager Part Time Youth Olympic Gold Medalist (UK) John Michelmore, Nick Stephenson and David England generously fill various coaching roles in an honourary capacity. Dan Wallace Operations Manger Full Time Virginia Lee Administrative Assistant Part Time Faith Anderson Finance Officer Part Time Future editions of the Newsletter will feature interviews with these important club officials. 1 \ MAY 2019 2019 Victorian State Championships MUBC saw great success at the 2019 Row- ing Victoria State Championships which took place on the first weekend of March at Nagambie. Beginning with the small boats races early in the day, our first success was seen with a win over Mercantile in a close race for the U23 Men’s pair, which consist- ed of Joe O’Connell and Edward Walms- ley. -

Annual Report 1979

THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE ANNUAL REPORT 1979 PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY CONTENTS Introduction 2 Council 3 The Professors 4 The Academic Board 4 Graduates of The University and The Graduate Committee . 5 The Faculties 6 The Library 30 Research 32 Office for Continuing Education .32 Finance 33 Buildings 37 Student Affairs 41 University Sport . 45 The Graduate Union 45 Melbourne University Press 46 Melbourne Theatre Company 47 The University Assembly 48 Staff 50 Gifts, Grants and Bequests 60 Statistics 74 Colleges and Halls of Residence 81 Scholarships, Exhibitions and Prizes 82 Degrees and Diplomas Conferred 96 ANNUAL REPORT Report on the proceedings of the University for the year ended 31 December, 1979. His Excellency, The Hon. Sir Henry Winneke, K.C.M.G., K.C.V.O., O.B.E., K.St.J., Q.C., Governor of Victoria. Your Excellency, The Council of the University of Melbourne has the honour, in accordance with Section 46 of the University Act 1958, to present the first part of its report on the proceedings of the University during the year 1979. In addition to a general account of University activities, Part One of the Annual Report includes a statement of income and expenditure in respect of the General Fund as submitted for audit. Part Two of the Annual Report, which will be issued later, will be the audited financial statements. I have the honour to be, Sir, Your Excellency's most obedient servant, OLIVER GILLARD Chancellor INTRODUCTION The year 1979 was the first of a new triennium, after three years of uncertainty for universities when it had not been possible to plan for more than one year at a time. -

2019 Event Program

AN OARSOME EXPERIENCE 2019 EVENT PROGRAM HOSTED BY STRATEGIC SPONSORS PRINCIPAL PARTNER MAJOR PARTNER Helping protect the future of Australian rowing clubs. Aon is proud to sponsor the Rowing Australia family and we wish all the competitors, coaches and volunteers at the Sydney International Rowing Regatta the best of luck! For more information visit aon.com.au/rowingaustralia 1800 377 712 | [email protected] © 2019 Aon Risk Services Australia Limited ABN 17 000 434 720 AFSL 241141 The information contained in this communication is general in nature and should not be relied on as advice (personal or otherwise) because your personal needs, objectives and financial situation have not been considered. Before deciding whether a particular product is right for you, please consider your personal circumstances, as well as the relevant Product Disclosure Statement (if applicable) and full policy terms and conditions available from Aon on request. All representations in relation to the insurance products we arrange are subject to the full terms and conditions of the relevant policy. Please contact us if you have any queries. AFF1031 0319 AN OARSOME EXPERIENCE CONTENTS WELCOME FROM THE NSW GOVERNMENT ........................................................................................... 4 ROWING AUSTRALIA ................................................................................................................................ 5 ROWING AUSTRALIA COUNCIL .............................................................................................................. -

Annual Report 1978

THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE ANNUAL REPORT 1978 PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY \n OF WfTg^ CONTENTS Introduction 2 Council 3 The Professors 3 The Academic Board 4 Graduates of The University and The Graduate Committee . 4 The Faculties 5 The Library 29 Research . 30 Office for Continuing Education 31 Finance 32 Buildings 35 Student Affairs 40 University Sport 44 The Graduate Union 45 Melbourne University Press 45 Melbourne Theatre Company 46 The University Assembly 47 Staff 49 Gifts, Grants and Bequests 60 Statistics 71 Colleges and Halls of Residence 78 Scholarships, Exhibitions and Prizes 79 Degrees and Diplomas Conferred 91 ANNUAL REPORT Report on the proceedings of the University for the year ended 31 December, 1978. His Excellency, The Hon. Sir Henry Winneke, K.C.M.G., K.C.V.O., O.B.E., K.St.J., Q.C., Governor of Victoria. Your Excellency, The Council of the University of Melbourne has the honour, in accordance with Section 46 of the University Act 1958, to present the first part of its report on the proceedings of the University during the year 1978. In addition to a general account of University activities, Part One of the Annual Report includes a statement of income and expenditure in respect of the General Fund as submitted for audit. Part Two of the Annual Report, which will be issued later, will be the audited financial statements. I have the honour to be, Sir, Your Excellency's most obedient servant, OLIVER GILLARD Chancellor INTRODUCTION The Annual Reports for 1975, 1976 and 1977 emphasized the uncer tainties created for universities by the fact that the Commonwealth Government did not adopt the recommendations of the Sixth Report of the Universities Commission in 1975, and by the steps taken by that Government which made it impossible for the universities to plan for more than a year at a time. -

PDF File 19.5 MB

Volume 2 Number 3 RoN 1 9 9 0 Jours lof the University of Melbourne Medical Society UMMS Vol. 2 No. 3 Contents April 1990 University of Melbourne 1 Editorial Peter G Jones Medical Society 2 Vale — Professor Emeritus Sir Douglas Wright As at 1 March 1990 4 Seminar — Resource Constraints and the Practice of Medicine: Everything That Might be Done Can't be Done President Pro f. Em. Richard Love!!, Hon. Senator Peter Baume, Prof. Em. Sir Sydney Sunderland Mr Kenneth Davidson, Dr Diana Horvath, Rev. Canon Dr John Morgan, Prof. Richard Larkins Executive Committee 15 The Link Between Alzheimer's Disease and Slow Virus Diseases of the Brain Colin L. Masters Chairman Professor Graeme Ryan 18 Hormones, Mood and Sexuality — from Freud to Feminism Lorraine Dennerstein Deputy Chairman 22 The New Era of Forensic Pathology Professor Gordon Clunie in Victoria Stephen M Cordner 28 The Ultimate in Preventive Medicine Robert L. Simpson Honorary Secretary 29 Books Harold D. Attwood Dr Diana Sutherland 30 Medical Records in The University of Melbourne Archives Frank Strahan Honorary Treasurer Mr David Westmore 34 UMMS • Notice of Annual General Meeting 1990 • Minutes of Annual General Meeting 1989 Dr Lorraine Baker (filling casual vacancy left by 35 • UMMS B.Med.Sc. Prize 1988 Dr Thomas Kay who is overseas) • Members News Dr John MacDonald Thomas Vicary Lecture 1989: James Guest Mr Michael Wilson 37 • Letters 38 • Reunions 41 School of Medicine Chiron • From the Dean Graeme B. Ryan Editors 44 • Reports from Clinical Schools Mr Peter Jones Austin Hospital & Repatriation Hospital Bernard Sweet Mrs Maggie Mackie Royal Melbourne Hospital and Western Hospital Alan M. -

Wellington Cultural History Bibliography

Cultural Heritage of Wellington Shire: A Bibliography The Smith family of Cowwarr, then Newry, c.1919-1922 2nd Edition 2012 Wellington Shire Heritage Network Cultural Heritage of Wellington Shire: A Bibliography First Edition Compiled by Linda Kennett Centre for Gippsland Studies Monash University For Wellington Shire Council 1999 Second Edition Updated by Linda Barraclough For Wellington Shire Heritage Network and Wellington Shire Library Service Foster Street, Sale 2012 Please note: a small number of the difficult-to-find titles have notes at the very end of the item in [square brackets] to show where the item may be consulted. Most are held at the Centre for Gippsland Studies, or in the Wellington Library Service. Please consult the online Wellington Library Service catalogue to enquire further. For corrections and to add details of further or new books, please e-mail Linda at [email protected] Further copies are available from Wellington Shire Heritage Network C/ Post Office, BOISDALE, 3860 Acknowledgements 2 nd Edition Melva James (Yarram and District Historical Society) Ann and Peter Synan Judy Hirst (Sale and District Family History Group) John Little (Maffra and District Historical Society) Dr Julie Fenwick, Centre for Gippsland Studies, Monash University. Cover Photographs “First and Second editions”: The Smith children, from Cowwarr and then “Parrambeen” at Newry. The parents were Horace Digby Smith and Catherine Maude nee Murphy. It is the same patient pony in both, name not recorded. The second photograph may have been taken at the Newry School, but confirmation is sought. (Courtesy Terry Hore) Table of Contents General Histories ............................................................................................................. 7 Aboriginal History .........................................................................................................