ARSC Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dorset-Opera-News-Christmas-2008

News Issue No: 7 Christmas 2008 Audience numbers And for 2009 it’s… Artistic Director, Roderick Kennedy, has chosen two unashamedly double in 2 years! popular works for Dorset Opera’s 2009 presentation: the most famous twins in all opera, Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana and Leoncavallo’s I pagliacci. Dorset Opera audience numbers have officially doubled over the last two years! Leonardo Capalbo as Nadir We might only operate on a small scale, but in a sparsely populated county like Dorset, such an increase is no mean feat. Opera companies around the world can only dream of such a marketing success. However, if audience numbers continue to increase at this rate, it is estimated that the demand for tickets will require us to present at least six performances by 2012. This would be extremely difficult to schedule, so from 2009 onwards, tickets could be in short supply. Ticket shortage There is already evidence that regular audience-goers are aware of a possible ticket shortage. More and more supporters are joining Cav and Pag as they are affectionately known, contain a mass of our Friends’ organisation in order to take advantage of priority well-known tunes for our chorus to get their teeth in to, and for our booking arrangements. loyal audiences to savour. The Easter Hymn, the Internezzo, and Santuzza’s aria Voi lo sapete… from Cav; the Prologue from Pag is The Pearl Fishers: we can dance, as well as sing! in every baritone’s repertoire, and the heart-rending tenor aria Vesti la giubba translated as On with the Motley, is sure to leave a tear in the eye. -

Chronology 1916-1937 (Vienna Years)

Chronology 1916-1937 (Vienna Years) 8 Aug 1916 Der Freischütz; LL, Agathe; first regular (not guest) performance with Vienna Opera Wiedemann, Ottokar; Stehmann, Kuno; Kiurina, Aennchen; Moest, Caspar; Miller, Max; Gallos, Kilian; Reichmann (or Hugo Reichenberger??), cond., Vienna Opera 18 Aug 1916 Der Freischütz; LL, Agathe Wiedemann, Ottokar; Stehmann, Kuno; Kiurina, Aennchen; Moest, Caspar; Gallos, Kilian; Betetto, Hermit; Marian, Samiel; Reichwein, cond., Vienna Opera 25 Aug 1916 Die Meistersinger; LL, Eva Weidemann, Sachs; Moest, Pogner; Handtner, Beckmesser; Duhan, Kothner; Miller, Walther; Maikl, David; Kittel, Magdalena; Schalk, cond., Vienna Opera 28 Aug 1916 Der Evangelimann; LL, Martha Stehmann, Friedrich; Paalen, Magdalena; Hofbauer, Johannes; Erik Schmedes, Mathias; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 30 Aug 1916?? Tannhäuser: LL Elisabeth Schmedes, Tannhäuser; Hans Duhan, Wolfram; ??? cond. Vienna Opera 11 Sep 1916 Tales of Hoffmann; LL, Antonia/Giulietta Hessl, Olympia; Kittel, Niklaus; Hochheim, Hoffmann; Breuer, Cochenille et al; Fischer, Coppelius et al; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 16 Sep 1916 Carmen; LL, Micaëla Gutheil-Schoder, Carmen; Miller, Don José; Duhan, Escamillo; Tittel, cond., Vienna Opera 23 Sep 1916 Die Jüdin; LL, Recha Lindner, Sigismund; Maikl, Leopold; Elizza, Eudora; Zec, Cardinal Brogni; Miller, Eleazar; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 26 Sep 1916 Carmen; LL, Micaëla ???, Carmen; Piccaver, Don José; Fischer, Escamillo; Tittel, cond., Vienna Opera 4 Oct 1916 Strauss: Ariadne auf Naxos; Premiere -

Programme Notes Olivia Sham

Programme Notes Olivia Sham FRANZ LISZT Années de pèlerinage Book II – Italie (1811-1886) 1. Sposalizio 2. Il penseroso 3. Canzonetta del Salvator Rosa LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Andante Favori WoO57 (1770-1827) CARL VINE Piano Sonata no.1 (b.1954) ~ Interval ~ OLIVIER MESSIAEN Vingt regards sur l'enfant-Jésus (1908-1992) 11. ‘Première communion de la vierge’ CLAUDE DEBUSSY Préludes Book II (1862-1918) 10. Canope 6. General Lavine – Eccentric FRANZ LISZT Années de pèlerinage Book II – Italie 4. Sonnetto 47 del Petrarca 5. Sonnetto 104 del Petrarca 6. Sonnetto 123 del Petrarca 7. Aprés une lecture du Dante: Fantasia quasi Sonata Having nothing to seek in present-day Italy, I began to scour her past; having but little to ask of the living, I questioned the dead. A vast field opened before me… In this privileged country I came upon the beautiful in the purest and sublimest forms. Art showed itself to me in the full range of its splendour; revealed itself in all its unity and universality. With every day that passed, feeling and reflection brought me to a still greater awareness of the secret link between works of genius…. Franz Liszt in 1839 (Translation by Adrian Williams) Before embarking on a touring career that would cement his reputation as the greatest of piano virtuosi, the young Franz Liszt travelled in Switzerland and Italy between 1837 and 1839 with his lover, the Countess Marie d’Agoult. He began then the first two books of the Années de Pèlerinage (Years of Pilgrimage), and the second volume of pieces, inspired by his time in Italy, was eventually published in 1858. -

The Latin American Musicologist

The Latin American Music Educator's Best Ally: the Latin American Musicologist Puper reud ut 1/ie V Conjer•mcia Jn1erumer1ca11a (l111trnucionull de Educució11 Musical. Mexico Ciry. Ocwbn 1979 T HE woRLO AT LARGE needs to know that Latin America enjoys an illustrious musical lineage. European music needs no advertisement. Already everyone knows that before Messiaen France boasted Debussy, Berlioz, Rameau, anda string of prior geniuses stretching back to Machaut. Similarly, everyone knows that before Stockhausen in Germany, before Berio and Nono in Italy, and before whomever else one might choose to name in Spain, England, Austria, Scandinavia and the Soviet Union, flourished national geniuses promulgated in every textbook. But what of Latín America? Granted, the world at large knows that before Manuel Enríquez, before Mario Lavista, and before Héctor Quintanar, Mexico boasted a Carlos Chávez and a Silvestre Revueltas. Even so, do not Mexican geniuses flourishing before 1900 tend to pale in the limelight of history? To date, Latin American musicologists have had considerable difficulty in communicating their findings to music educators, so much so that even in the most advanced circles, litera ti still fail to recognize the namcs of many of the truly great composers born in Mexico before Chávez, Revueltas, and Bias Galindo Dimas. Every literate Latin American at least knows who Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz was. But how many know even the name of that superlative composer, born and educated at Mexico City (where he died in 1674), Francisco López Capillas? Or the name of Manuel Zumaya, likewise born and educated at Mexico City (but buried at Oaxaca where he died in 1754)? Here then musicologists and music educators must join hands: first to make more widely known the names of the past musical geniuses of Latín America and second to integrate the music of those prior national stalwarts into the curricula of national con servatories. -

Horne-Part-Ii-A-L.Pdf

J & J LUBRANO MUSIC ANTIQUARIANS Marilyn Horne in Norma by John Foote: National Portrait Gallery, Washington D.C. Autographs, Prints, & Memorabilia from the Collection of Marilyn Horne Part 2: A-L 6 Waterford Way, Syosset, NY 11791 USA Telephone 516-922-2192 [email protected] www.lubranomusic.com CONDITIONS OF SALE Please order by catalogue name (or number) and either item number and title or inventory number (found in parentheses preceding each item’s price). Please note that all material is in good antiquarian condition unless otherwise described. All items are offered subject to prior sale. We thus suggest either an e-mail or telephone call to reserve items of special interest. Orders may also be placed through our secure website by entering the inventory numbers of desired items in the SEARCH box at the upper right of our homepage. We ask that you kindly wait to receive our invoice to insure availability before remitting payment. Libraries may receive deferred billing upon request. Prices in this catalogue are net. Postage and insurance are additional. New York State sales tax will be added to the invoices of New York State residents. We accept payment by: - Credit card (VISA, Mastercard, American Express) - PayPal to [email protected] - Checks in U.S. dollars drawn on a U.S. bank - International money order - Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT), inclusive of all bank charges (details at foot of invoice) - Automated Clearing House (ACH), inclusive of all bank charges (details at foot of invoice) All items remain the property of J & J Lubrano Music Antiquarians LLC until paid for in full. -

The Juilliard Manuscript Collection

The Juilliard Manuscript Collection Composer Title Brief Description Arensky, Anton Scherzo, op. 8, for piano Fine autograph manuscript of the “Scherzo” Op. 8 for piano, signed (“Ant. Arensky”), in A major, written in black ink on three systems per page, each of two staves, with deletions, revisions and alterations, some bars represented only by numbers in repeated passages, dedication to Vassily Il’yich Safonov on first page of music. Bach, J. S. Cantata ‘Es ist ein trotzig und The lost manuscript of the transposed continuo part of the cantata ‘Es is ein trotzig und verzagt Ding’ BWV 176 verzagt ding’, BWV 176, from the original set of performing materials for the premiere in Leipzig on 27 May 1725. Bach, J.S. Choräle der Sammlung, Leipzig, 1765 C.P.E. Bach (Chorales from the C.P.E. Bach collection) Bach, J.S. Keyboard music, selections Clavier Übung bestehend in Praeludien… von Johann Sebastian Bach…Directore Chori (Clavier-Übung) Musici Lipsiensis. Opus 1, Leipzig, the author (“In Verlegung des Autoris”), Leipzig, 6 Partitas BWV 825-830 1731 Bach, J.S. St. Matthew Passion and First editions of the “St Matthew Passion” and the “St John Passion” in full score, Berlin, St. John Passion 1830, 1831. Bach, J.S. Kunst der Fuge First Edition, second issue [?], Leipzig, 1752 Barber, Samuel Antony and Cleopatra Autograph musical notebook with directions for cuts and alterations to Act II (sketches) Beethoven, Fidelio Important working manuscript of part of Fidelio, extensively revised by the composer, Ludwig van unsigned, being a scribal manuscript -

A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS of LISZT's SETTINGS of the THREE PETRARCHAN SONNETS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North T

$791 I' ' Ac A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF LISZT'S SETTINGS OF THE THREE PETRARCHAN SONNETS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Johan van der Merwe, B. M. Denton, Texas December, 1975 van der Merwe, Johan, A Stylistic Analysis of Liszt's Settings of the Petrarchan Sonnets. Master of Arts (Music), December, 1975, 78 pp., 31 examples, appendix, 6 pp., biblio- graphy, 64 titles. This is a stylistic study of the four versions of Liszt's Three Petrarchan Sonnets with special emphasis on the revi- sion of poetic settings to the music. The various revisions over four versions from 1838 to 1861 reflect Liszt's artis- tic development as seen especially in his use of melody, harmony, tonality, color, tone painting, atmosphere, and form. His use of the voice and development of piano tech- nique also play an important part in these sonnets. The sonnets were inexplicably linked with the fateful events in his life and were in a way an image of this most flamboyant and controversial personality. This study suggests Liszt's importance as an innovator, and his influence on later trends should not be underestimated. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS..........0.... ..... .... iv Chapter I. INTRODUCTION. ......... ......... 1 II. A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF LISZT'S SETTINGS OF THE THREE PETRARCHAN SONNETS......a..... 13 Sonnet no. 47, "Benedetto sia '1 giorno" Sonnet no. 104, "Pace non trovo" Sonnet no. 123, "I' vidi in terra angelici costumi" III. CONCLUSION . .*.* .0.0 .a . -

Senior Recital: Christina Ruth Grace Vehar, Mezzo-Soprano

Kennesaw State University School of Music Senior Recital Christina Ruth Grace Vehar, mezzo-soprano Brenda Brent, piano Sunday, May 7, 2017 at 4 pm Music Building Recital Hall Seventieth Concert of the 2016-17 Concert Season program I. GIOVANNI PERGOLESI (1710-1736) Se tu m’ami SALVATOR ROSA (1615-1673) Star Vicino GIOVANNI BATTISTA BONONCINI (1670-1747) Non posso disperar II. GABRIEL FAURÉ (1845-1924) Rêve d'amour HENRI DUPARC (1848-1933) Chanson Triste GABRIEL FAURÉ (1845-1924) Au bord de l'eau III. WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756-1791) Das Veilchen FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828) An Die Musik ROBERT SCHUMANN (1810-1856) Widmung IV. HENRY PURCELL (1659-1695) Nymphs and Shepherds THOMAS ARNE (1710-1778) When Daisies Pied SAMUEL BARBER (1910-1981) The Daisies JOHN DUKE (1899-1984) Loveliest of Trees V. JOHN NEWTON (1725-1807) DOLLY PARTON (b. 1942) arr. Craig Hella Johnson Amazing Grace / Light of a Clear Blue Morning Alison Mann, conductor Choir: Emily Bateman, Emma Bryant, Benjamin Cubitt, Brittany Griffith, Cody Hixon, Chase Law, Caty Mae Loomis, Angee McKee, Rick McKee, Shannan O'Dowd, Marielle Reed, Hannah Smith, Forrest Starr This recital is presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree Bachelor of Music in Music Education. Ms. Vehar studies voice with Eileen Moremen. program notes I. Se tu m’ami | Giovanni Pergolesi Pergolesi was a composer known for his church music, his most popular being Stabat Mater – which became the most printed composition in the 1700s. He also found posthumous success for his opera La serva pedrona. The aria Se tu m’ami sets the scene of a young woman teasing a shepherd, and Pergolesi enhances this story through an ABA (ternary) form with the A section portraying the young woman and the B section portraying the frustrated shepherd boy. -

THE RECORD COLLECTOR MAGAZINE Given Below Is the Featured Artist(S) of Each Issue (D=Discography, B=Biographical Information)

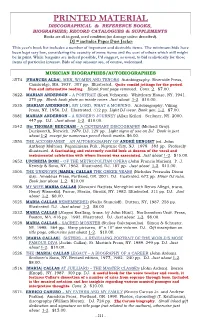

PRINTED MATERIAL DISCOGRAPHICAL & REFERENCE BOOKS, BIOGRAPHIES; RECORD CATALOGUES & SUPPLEMENTS Books are all in good, used condition (no damage unless described). DJ = includes Paper Dust Jacket This year’s book list includes a number of important and desirable items. The minimum bids have been kept very low, considering the scarcity of some items and the cost of others which still might be in print. While bargains are indeed possible, I’d suggest, as usual, to bid realistically for those items of particular interest. Bids of any amount are, of course, welcomed. MUSICIAN BIOGRAPHIES/AUTOBIOGRAPHIES 3574. [FRANCES ALDA]. MEN, WOMEN AND TENORS. Autobiography. Riverside Press, Cambridge, MA. 1937. 307 pp. Illustrated. Quite candid jottings for the period. Fun and informative reading. Blank front page removed. Cons. 2. $7.00. 3622. MARIAN ANDERSON – A PORTRAIT (Kosti Vehanen). Whittlesey House, NY. 1941. 270 pp. Blank book plate on inside cover. Just about 1-2. $10.00. 3535. [MARIAN ANDERSON]. MY LORD, WHAT A MORNING. Autobiography. Viking Press, NY. 1956. DJ. Illustrated. 312 pp. Light DJ wear. Book gen. 1-2. $7.00. 3581. MARIAN ANDERSON – A SINGER’S JOURNEY (Allan Keiler). Scribner, NY. 2000. 447 pp. DJ. Just about 1-2. $10.00. 3542. [Sir THOMAS] BEECHAM – A CENTENARY DISCOGRAPHY (Michael Gray). Duckworth, Norwich. 1979. DJ. 129 pp. Light signs of use on DJ. Book is just about 1-2 except for numerous pencil check marks. $6.00. 3550. THE ACCOMPANIST – AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF ANDRÉ BENOIST (ed. John Anthony Maltese). Paganiniana Pub., Neptune City, NJ. 1978. 383 pp. Profusely illustrated. A fascinating and extremely candid look at dozens of the vocal and instrumental celebrities with whom Benoist was associated. -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Department of Music Volume 2 of 2 Heinrich Schenker and the Radio by Kirstie Hewlett Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2014 1 1 Appendices 1 1 Contents Appendix 1: References to Radio Broadcasts.............................................................. 1 1924 ........................................................................................................................................................................ 3 1925 ......................................................................................................................................................................11 1926 ......................................................................................................................................................................53 -

78Rpm to Sell !

Beginning ! ! 78rpm to sell ! ! ! Albums : Lotte Lehmann : Schubert + Schumann + Brahms (3x) Columbia US Sir Charles Thomas Victor Grace Moore Lily Pons Mario Lanza Yves Thymaire Voices of the Golden age (volume 1 Victor) Gilbert & Sullivan Princess Ida HMV OA + HMS Pinafore Decca Vaughan Williams On wenlock wedge Pears Jeaette Mc Donald in songs Blanche Thebom Schumann Jennies Tourel Offenbach Dorothy Maynor Spirituals Hulda Lahanska Lieder recital Erna Sack Popular favorites Eileen Farrell Irish songs Paul Robeson Spirituals Josef Schmidt Lotte Lehmann Strauss Lotte Lehmann Song recital Maggie Teyte French art songs Gladys Swarthout pˆopular favorites Maggie Teyte Debussy with Cortot Lotte Lehmann Schumann with Bruno Walter Lotte Lehmann Brahms Index Ada ASLOP, 44 Alma GLUCK, 38, 51 Ada NORDENOVA, 96, 97 Amelita GALLI-CURCI, 27, 30, 32, 57, 63, 72 Adamo DIDUR, 99 Anne ROSELLE, 25 Adele KERN, 17, 18, 46, 74, 77 Anny SCHLEMM, 45 Alda NONI, 14, 17, 48, 60, 74 Anny von STOSCH, 91 Alessandro BONCI, 57 Antenore REALI, 40 Alessandro VALENTE, 58, 67 Antonio CORTIS, 58, 60 Alexander KIPNIS, 71, 72, 77 Antonio SCOTTI, 30 Alexander SVED, 47 Armand TOKATYAN, 65 Alexandra TRIANTI, 76 Arno SCHELLENBERG, 71 Alexandre KOUBITSKY, 49 Arthur ENDREZE, 61, 85, 86 Alexandre KRAIEFF, 23 Arthur PACYNA, 58 Alfons FUGEL, 40 Astra DESMOND, 41, 59 Alfred JERGER, 57 August SEIDER, 47 Alfred PICCAVER, 25, 26, 96 Augusta OLTRABELLA, 46, 87 Alina BOLECHOWSKA, 46 Aulikki RAUTAWAARA, 100 Barbara KEMP, 23 Cesare FORMICHI, 99 Bernardo de MURO, 32, 50 Cesare PALAGI, 78 Bernhard -

PRINTED MATERIAL DISCOGRAPHICAL & REFERENCE BOOKS, PAMPHLETS, BIOGRAPHIES; PROGRAMS Books Are All in Good, Used Condition (No Damage Unless Described)

PRINTED MATERIAL DISCOGRAPHICAL & REFERENCE BOOKS, PAMPHLETS, BIOGRAPHIES; PROGRAMS Books are all in good, used condition (no damage unless described). “As new” should be just that. “Excellent” would be similar to 2, light dust jacket or cover marks but no problems. “Good” would be similar to 3 (use wear). Any damage or marking is mentioned. DJ = includes Paper Dust Jacket “THE RECORD COLLECTOR” MAGAZINE Given below is the featured artist(s) of each issue (D=discography, B-biographical sketch). All copies are in fine condition (with the possibility of an index mark or possible check marks, occasional underlinings, but no physical damage such as tears, loose seams, etc., unless otherwise indicated. MINIMUM BID $5.00 PER MAGAZINE 8002. II/1-6. (Jan.-June, 1947). Re-issue of first half of Volume II, originally in mimeographed format. 8006. III/3. Götterdämmerung on Records; The Victor News Letter; American Record Notes, etc. 8007. III/4. Rethberg Discography; more Götterdämmerung; Cloe Elmo; Russian Operatic Discs, etc. 8010. III/7. Dating Victor Records; A Brief Glance Back; More “Historical Record” Amendments, etc. 8011. III/8. Iris addenda; Russian Operatic Records; More on Affre; The Aldeburgh Festival, etc. 8012. III/9. Edison Disc Records; Celebrities at Birmingham; Puccini Operas; More on Götterdämmerung, etc. 8013. III/10. A Santley Curiosity; Matrix & Serial Numbers; My Most Inartistic Recording; etc. 8015. III/12. Bauer Amendments; Italian Vocal Issues Jan.-Aug. 1948; Philadelphia Record Society, etc. 8017. IV/2. Giovanni Zenatello (D); “Otello” discography, etc. 8018. IV/3. Medea Mei-Figner (D); Another Curiosity; Italian Vocal Issues, etc. 8019. IV/4 The DeReszke Mystery; Eugenia Mantelli (D and commentary), To Help the Junior Collector, etc.