Complete Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pan Macmillan AUTUMN CATALOGUE 2021 PUBLICITY CONTACTS

Pan Macmillan AUTUMN CATALOGUE 2021 PUBLICITY CONTACTS General enquiries [email protected] Alice Dewing FREELANCE [email protected] Anna Pallai Amy Canavan [email protected] [email protected] Caitlin Allen Camilla Elworthy [email protected] [email protected] Elinor Fewster Emma Bravo [email protected] [email protected] Emma Draude Gabriela Quattromini [email protected] [email protected] Emma Harrow Grace Harrison [email protected] [email protected] Jacqui Graham Hannah Corbett [email protected] [email protected] Jamie-Lee Nardone Hope Ndaba [email protected] [email protected] Laura Sherlock Jess Duffy [email protected] [email protected] Ruth Cairns Kate Green [email protected] [email protected] Philippa McEwan [email protected] Rosie Wilson [email protected] Siobhan Slattery [email protected] CONTENTS MACMILLAN PAN MANTLE TOR PICADOR MACMILLAN COLLECTOR’S LIBRARY BLUEBIRD ONE BOAT MACMILLAN Nine Lives Danielle Steel Nine Lives is a powerful love story by the world’s favourite storyteller, Danielle Steel. Nine Lives is a thought-provoking story of lost love and new beginnings, by the number one bestseller Danielle Steel. After a carefree childhood, Maggie Kelly came of age in the shadow of grief. Her father, a pilot, died when she was nine. Maggie saw her mother struggle to put their lives back together. As the family moved from one city to the next, her mother warned her about daredevil men and to avoid risk at all cost. Following her mother’s advice, and forgoing the magic of first love with a high-school boyfriend who she thought too wild, Maggie married a good, dependable man. -

The Jazz Record

oCtober 2019—ISSUe 210 YO Ur Free GUide TO tHe NYC JaZZ sCene nyCJaZZreCord.Com BLAKEYART INDESTRUCTIBLE LEGACY david andrew akira DR. billy torn lamb sakata taylor on tHe Cover ART BLAKEY A INDESTRUCTIBLE LEGACY L A N N by russ musto A H I G I A N The final set of this year’s Charlie Parker Jazz Festival and rhythmic vitality of bebop, took on a gospel-tinged and former band pianist Walter Davis, Jr. With the was by Carl Allen’s Art Blakey Centennial Project, playing melodicism buoyed by polyrhythmic drumming, giving replacement of Hardman by Russian trumpeter Valery songs from the Jazz Messengers songbook. Allen recalls, the music a more accessible sound that was dubbed Ponomarev and the addition of alto saxophonist Bobby “It was an honor to present the project at the festival. For hardbop, a name that would be used to describe the Watson to the band, Blakey once again had a stable me it was very fitting because Charlie Parker changed the Jazz Messengers style throughout its long existence. unit, replenishing his spirit, as can be heard on the direction of jazz as we know it and Art Blakey changed By 1955, following a slew of trio recordings as a album Gypsy Folk Tales. The drummer was soon touring my conceptual approach to playing music and leading a sideman with the day’s most inventive players, Blakey regularly again, feeling his oats, as reflected in the titles band. They were both trailblazers…Art represented in had taken over leadership of the band with Dorham, of his next records, In My Prime and Album of the Year. -

I Wanna Be Yours - John Cooper Clarke

Edexcel English Literature GCSE Poetry Collection: Relationships i wanna be yours - John Cooper Clarke This work by PMThttps://bit.ly/pmt-edu-cc Education is licensed under https://bit.ly/pmt-ccCC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://bit.ly/pmt-cc https://bit.ly/pmt-edu https://bit.ly/pmt-cc I WANNA BE YOURS John Cooper Clarke Brief Summary The poem features an unknown speaker addressing their lover, who is also unknown to the reader. The speaker asks to be let into every aspect of their lover’s life by listing the different mundane, everyday objects they want to replace. As well as asking to be needed and adored by their lover, the speaker demonstrates their devotion to their lover and the consistency of their affection. The exact relationship between the speaker and the object of their affection is unknown, but it is clear that the speaker wants to be closer to the person they are addressing. The poem is full of simplistic language, word play, and innuendo. Synopsis ● The speaker is talking directly to an unknown subject and we never hear their response to the speaker ● The speaker asks their lover if they will “let” them take the place of various everyday objects in their life ● The speaker makes it clear that their lover is in control ● The only thing the speaker desires is to belong to their lover ● The list of mundane objects continues as the speaker makes it clear that they want to make their lover’s life better and be with them everywhere ● The final stanza finishes with a grander, more metaphysical (deep) image than the mundane objects previously used to show the extent of the speaker’s devotion ● The speaker concludes by clarifying they want no one else other than the lover they are addressing in this poem Context John Cooper Clarke (1949 - present) John Cooper Clarke was born in Salford, Lancashire, in the north of England. -

Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers Moanin Mp3 Free

Art blakey and the jazz messengers moanin mp3 free Watch the video, get the download or listen to Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers – Moanin' for free. Moanin' appears on the album Moanin'. Before "soul" had. Art Blakey Amp Jazz Messengers Moanin MB · Moanin. Artist: Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers. ART BLAKEY amp THE JAZZ MESSENGERS MOANIN free download mp3. ART BLAKEY free downloads mp3 Free Music Downloads. Download Moanin art. Download Art Blakey and The Jazz Messengers mp3. Art Blakey and The Jazz Messengers download high quality complete mp3 albums. Buy the CD album for £ and get the MP3 version for FREE. Does not apply to gift orders. Provided by Amazon EU Sàrl. See Terms and Conditions for. not apply to gift orders. Complete your purchase to save the MP3 version to your music library. This item:Free For All by Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers Audio CD $ In Stock. Ships from .. Moanin' Audio CD. Art Blakey and the. on orders over $25—or get FREE Two-Day Shipping with Amazon Prime. In Stock . This item:Moanin' [LP] by Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers Vinyl $ Complete your purchase to save the MP3 version to your music library. This item's packaging may This item:Free for All [LP] by Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers Vinyl $ In Stock. Ships from .. Moanin' Audio CD. Art Blakey and the. A new video, hope you like it and comment and rate! En la historia del jazz no abundan los baterías que dirigen grupos u orquestas; menos aun, los que han. Moanin' Album: Moanin' () Written by: Bobby Timmons Personnel: Art Blakey — drums Lee Morgan. -

SUMMER 2016 Www

Box Office 0504 90204 SUMMER 2016 www.thesourceartscentre.ie www. thesourceartscentre.ie The Source Arts Centre Summer 2016 Programme The days are finally getting brighter and a little warmer so it’s a good time to get out of the house and come to the Source to see a few events. We’ve got a good selection of musical acts – the highly tipped Dublin songwriter Anderson who became famous for selling his album door-to-door, arrives for a solo show; Cork-born songwriter Mick Flannery presents his new album in another solo gig and we’ve opened up the auditorium for some tribute shows like Live Forever and Roadhouse Doors to give a more concert-type feel, so check these out on our brochure. Legendary Manchester poet John Cooper Clarke comes to visit us on May 4th; we have theatre with ‘The Corner Boys’, God Bless The Child’ and Brendan Balfe reminisces about the golden days of Irish radio in early June. Summer is a time for the kids and again we have a series of arts workshops and classes running over the summer months to keep them all occupied. Keep a lookout for our website: www.thesourceartscentre.ie for updates to our programme as we regularly add new events. Addtionally we put updates on our Facebook page. If you wish to be included on our mailing list, just get in contact with us at: boxoffice @sourcearts.ie We look forward to seeing you at The Source during the summer Brendan Maher Artistic Director Buy online Stef Hans open at You can choose your preferred seat when you The Source Arts Centre buy online 24/7 via your laptop, tablet or smart Fine day-time cuisine from award winning phone at www.thesourceartscentre.ie. -

Smooth Talk Smooth Carol Horn Vintage

FASHION: s EYE: Ginnifer Goodwin becomes a romantic Natalia lead, page 4. Vodianova For more, see unveils WWD.com. lingerie, NEWS: Industry anxious as swim line, s Obama repositions China page 5. s trade policy, page 3. Women’s Wear Daily • The Retailers’ Daily Newspaper • February 9, 2009 • $3.00 WAccessories/Innerwear/LegwearwDMONdAY Smooth Talk Some lingerie designers like their luxury simple: easy, no-frills shapes in rich materials. Here, some examples: Chris Arlotta’s cashmere sweater, T-Luxury’s cotton and modal tank top for Anthropologie and Josie Natori’s silk tap shorts; necklace by Carol Horn vintage. For more, see pages 6 and 7. Forget Fashion Flash: Philo Rested and Ready For a Sensible Celine By Miles Socha PARIS — Phoebe Philo, one of the biggest fashion stars of her generation, is getting ready for her comeback after three years on the sidelines. And her first designs for Celine, to be unveiled in June for the pre-spring and cruise seasons, sound like they’re in tune with the times, underlining how much the industry has changed. Fireworks are out: Realism is in. “[Celine] RYAN TANIGUCHI USING TRESEMME; STYLED BY BOBBI QUEEN USING TRESEMME; STYLED BY TANIGUCHI RYAN never stood for flashy fashion. It always felt BY like it was pretty sober, and that feels really relevant,” Philo said in her first interview since taking the creative helm of the brand, owned by luxury giant LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton. “It’s going to be more about a MIZU FOR SUSAN PRICE; HAIR foundation for a wardrobe.” BY See Back, Page8 PHOTO BY KYLE ERICKSEN; MODEL: AGNESA/RED; MAKEUP KYLE PHOTO BY 2 WWD, MONDAY, FEBRUARY 9, 2009 WWD.COM Christian Dior Sales Flat in ’08; Rtw, Luxe Bags On Growth Track WWDAccessories/Innerwear/LegwearMONDAY By Miles Socha said, disclosing that Dior bou- FASHION tiques in Palm Beach and Puerto Lingerie designers have a new energy for fall, PARIS — Christian Dior Couture Rico recently were shuttered. -

Warwickshire Cover

Worcestershire Cover Online.qxp_Birmingham Cover 29/07/2016 10:58 Page 1 Your FREE essential entertainment guide for the Midlands ISSUE 368 AUGUST 2016 JIMMY OSMOND Worcestershire OUT ON NEW UK TOUR ’ WhatFILM I COMEDY I THEATRE I GIGS I VISUAL ARTS I EVENTSs I FOOD On worcestershirewhatson.co.uk inside: Yourthe 16-pagelist week by week listings guide PRESENT LAUGHTER NOËL COWARD’S COMEDY ARRIVES AT MALVERN THEATRES Donington F/P - August '16.qxp_Layout 1 25/07/2016 10:08 Page 1 Contents August Warwickshire/Worcs.qxp_Layout 1 25/07/2016 12:09 Page 1 August 2016 Contents The Rover - Aphra Behn’s play returns to the Swan Theatre. Feature page 8 Julian Marley Sir Antony Sher Spectacular Science the list Reggae superstar embarks on Award-winning actor takes on Brand new show to dispel Your 16-page his first ever UK tour King Lear at the RSC ‘science is boring’ myth... week-by-week listings guide page 14 page 30 page 26 page 51 inside: 4. First Word 11. Food 14. Music 26. Comedy 28. Theatre 37. Film 40. Visual Arts 43. Events fb.com/whatsonwarwickshire fb.com/whatsonworcestershire @whatsonwarwicks @whatsonworcs Warwickshire What’s On Magazine Worcestershire What’s On Magazine Warwickshire What’s On Magazine Worcestershire What’s On Magazine Managing Director: Davina Evans [email protected] 01743 281708 ’ Sales & Marketing: Matt Rothwell [email protected] 01743 281719 Lei Woodhouse [email protected] 01743 281703 Whats On Chris Horton [email protected] 01743 281704 MAGAZINE GROUP Editorial: Lauren Foster [email protected] -

The New Classics

Spine: 5/32” (.1563”) Varnish: Knockout “WSJ.” in main logo THE NEW CLASSICS what to collect now 0613_WSJ_Cover_02.indd 1 4/25/13 7:43 AM ADDRESSED to THE NINES A COLLECTION OF THE FINEST 2-5 BEDROOM LUXURY RESIDENCES FROM $2.9M AT THE FASHIONABLE INTERSECTION OF EAST 61ST AND MADISON AVENUE SALES BOUTIQUE: 660 MADISON AVENUE, NEW YORK, NY The complete offering terms are in an offering plan available from Sponsor. File No C11-0007. Sponsor is 680 Residential Owner LLC, c/o Extell Development Company, 805 Third Avenue, Seventh Floor, New York, New York 10022. Equal Housing Opportunity. TheCarltonHouse.com | 212 680 0166 CHIC ON THE BRIDGE - NEW YORK Sold exclusively in Louis Vuitton stores and on louisvuitton.com. Pink gold, diamonds and ceramic. Automatic movement. www.dior.com - 1-866-675-2078 www.dior.com - 1-866-675-2078 40-hour power reserve. New York 717 MadisoN aveNue 212.644.4499 east HaMptoN 23 MaiN street 631.604.5050 devikroell.coM 100/100 And it will only get finer with time. The 2008 Grange has been awarded a perfect score by Robert Parker’s Wine Advocate, a respected publication. Over time there have been some extraordinary vintages – an unbroken line since 1951 proves it – but a number have been exceptional. An outstanding vintage release, the 2008 is highly anticipated by collectors around the world. penfolds.com Private cellar, Buckinghamshire, UK. cartier 0- 80 1- s - .u artier .c www june 2013 14 EDITOR’S LETTER 18 COnTRIbuTORS 20 COLumnISTS on Intuition 96 STILL LIfE Inès de la fressange The longtime model, and consultant for Roger Vivier, shares her prized possessions. -

Punk Scholars Network Conference

Welcome Overview of the Day Welcome to the University of Northampton and ‘The Art of 09:00-9:30 Registration Punk’ conference, held in association with the Punk Scholars 09:30-10:15 Welcome video from Nick Petford, Network. It is with great pleasure that Roy and I welcome you Vice Chancellor of The University of to both the university and the conference. Northampton Keynote Address: Pete Lyons (Antisect) We are very excited to be hosting such a fascinating array of 10:15:10:30 Coffee papers, which draw on the diverse facets of all things punk. 10:30-12:00 Session One – Three Parallel Panels Thank you so much for everyone’s hard work in putting this 12:00-12:45 Lunch conference together. We will be using #ArtofPunk on Twitter 12:45-13:55 Exhibition & Screening of Zillah Minx’s throughout the conference, do please feel free to use this as She’s a Punk Rocker U.K. you wish, to connect with each other and offer thoughts, 13:55-14:00 Welcome back from John Sinclair, Dean comments and feedback. of Faculty, Arts, Science & Technology 14:00-15:30 Session Two – Three Parallel Panels We hope we can use today to not only expand, develop and 15:30-16:00 Coffee explore our thinking, knowledge and approach to punk, but 16:00-17:30 Session Three – Three Parallel Panels also to further establish and maintain academic interest and 17:30-18:30 Wine Q&A: Richard Boon, Malcolm investigation in the subject for the future. Garrett & Zillah Minx (Hosted by Pete Lyons) ‘Do they owe us a living?’… 18:30-18:35 Closing Remarks by Claire Allen & Roy Wallace Claire -

Belfast Festival 2012 Programme

19 october - 4 november 2012 FESTIVAL Programme 02 CONTENTS 50th Ulster Bank Belfast Festival At Queen’s 50th Ulster Bank Belfast Festival At Queen’s WELCOME 03 INTRO 03 C Classical celebrate 04 Com Comedy Anthology 08 D Dance world classy 10 F Film engage 19 Fam Family homegrown 24 T Talks the beautiful game 28 TH Theatre let’s dance 31 TWJP Trad/World/Jazz/Pop headliners 36 SA Sonic Arts delight 40 VA Visual Arts WELCOME INTRODUCTION mexico 48 The 50th Festival. What an exciting season. What a The 50th Belfast Festival at Queen’s presents the re-imagine 50 wonderful achievement. opportunity to reflect on what has been achieved over In 1961 a group of young Queen’s students organised the the years and to remember what makes this cultural graphic grrRls 54 first arts festival at the University. Modest in scope compared extravaganza so special. It is breath-taking to consider the to today, it nonetheless shone with ambition and it had a number of people who, over the last five decades, have innovate 56 sense of purpose - only the best will do. played their part in creating Festival’s cultural legacy. From those early days the Queen’s Festival - now the Ulster From artists and performers, venues and audiences, inspire 61 Bank Belfast Festival at Queen’s - has indeed been bringing volunteers and staff through to our patrons and supporters us the best, and in doing so it has placed this city firmly on all have helped Festival on its journey and ensured that it 50 shades of green 64 the map as a centre of cultural importance. -

Gregoryh.Pdf (PDF, 1.334Mb)

Texts in Performance: Identity, Interaction and Influence in U.K. and U.S. Poetry Slam Discourses Submitted by Helen Gregory, to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology, July 2009. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. ......................................................................................... Texts in Performance: Identity, Interaction and Influence in U.K. and U.S. Poetry Slam Discourses Acknowledgements After a research project representing several years of full time research there is inevitably a long list of people to thank. In particular, this research would not have been possible without the generosity and support of countless members of slam and performance poetry communities in the U.K. and U.S.. I would particularly like to thank: Mee Ng, Ebele Ajogbe, Alvin Lau and Soul and Donna Evans, who offered up their homes, spare beds and sofas to me; everyone who spent valuable hours talking to me about performance poetry and slam, in particular Kurt Heintz, Matthias Burki, Jacob Sam-La Rose and the late Pat West who each sent me lengthy and informative e-mails; Jenny Lindsay and Russell Thompson for offering me their guest tickets to the fantastic Latitude Festival in 2006; and my good friend Paul Vallis, who endured many hours of research-related monologues. -

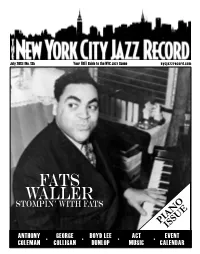

Stompin' with Fats

July 2013 | No. 135 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com FATS WALLER Stompin’ with fats O N E IA U P S IS ANTHONY • GEORGE • BOYD LEE • ACT • EVENT COLEMAN COLLIGAN DUNLOP MUSIC CALENDAR “BEST JAZZ CLUBS OF THE YEAR 2012” SMOKE JAZZ & SUPPER CLUB • HARLEM, NEW YORK FEATURED ARTISTS / 7pm, 9pm & 10:30 ONE NIGHT ONLY / 7pm, 9pm & 10:30 RESIDENCIES / 7pm, 9pm & 10:30 Mondays July 1, 15, 29 Friday & Saturday July 5 & 6 Wednesday July 3 Jason marshall Big Band Papa John DeFrancesco Buster Williams sextet Mondays July 8, 22 Jean Baylor (vox) • Mark Gross (sax) • Paul Bollenback (g) • George Colligan (p) • Lenny White (dr) Wednesday July 10 Captain Black Big Band Brian Charette sextet Tuesdays July 2, 9, 23, 30 Friday & Saturday July 12 & 13 mike leDonne Groover Quartet Wednesday July 17 Eric Alexander (sax) • Peter Bernstein (g) • Joe Farnsworth (dr) eriC alexaNder QuiNtet Pucho & his latin soul Brothers Jim Rotondi (tp) • Harold Mabern (p) • John Webber (b) Thursdays July 4, 11, 18, 25 Joe Farnsworth (dr) Wednesday July 24 Gregory Generet George Burton Quartet Sundays July 7, 28 Friday & Saturday July 19 & 20 saron Crenshaw Band BruCe Barth Quartet Wednesday July 31 Steve Nelson (vibes) teri roiger Quintet LATE NIGHT RESIDENCIES Mon the smoke Jam session Friday & Saturday July 26 & 27 Sunday July 14 JavoN JaCksoN Quartet milton suggs sextet Tue milton suggs Quartet Wed Brianna thomas Quartet Orrin Evans (p) • Santi DeBriano (b) • Jonathan Barber (dr) Sunday July 21 Cynthia holiday Thr Nickel and Dime oPs Friday & Saturday August 2 & 3 Fri Patience higgins Quartet mark Gross QuiNtet Sundays Sat Johnny o’Neal & Friends Jazz Brunch Sun roxy Coss Quartet With vocalist annette st.