Rousseau's Idea of Theatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Augustine and Rousseau on the Politics of Confession

Augustine and Rousseau on the Politics of Confession by Taylor Putnam A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014, Taylor Putnam Abstract This thesis looks at the widely acknowledged but largely unexplored relationship between Augustine’s Confessions and Rousseau’s Confessions. In particular, it argues that Rousseau’s text demonstrates an indebtedness to both Augustine’s treatment of time within eternity and the political figure of the Christian preacher. By first comparing their competing interpretations of original sin as told in Genesis and then tracing those interpretations through the autobiographical narratives of each text, it is argued that Augustine and Rousseau both offer their lives as examples of their respective understandings of human nature. Further still, Rousseau’s attempt to supplant Augustine’s autobiography with his own sees the Augustinian preacher reformulated into the figure of the solitary walker. As a result, what was a politics of the will restrained by the temporal horizon of man becomes unleashed as the imposition of the timeless imagination. i Acknowledgments I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Professor Newell for his willingness to have me as a graduate student and for supervising my thesis. He generously provided me with the opportunity to pursue this education and I will be forever thankful for it. I would also like to thank Professor Darby for being my second reader and, more importantly, for his unwavering support throughout my degree. Lastly, I would like to thank my parents who in their wisdom gave me the freedom to fail and demystified what is required to learn. -

Table 7-1 French Opera Repertory 1753–62

1 Table 12-1 French Opera Repertory 1753–63 (with Court performances of opéras- comiques in 1761–63) See Table 1-1 for the period 1742–52. This Table is an overview of commissions and revivals in the elite institutions of French opera. Académie Royale de Musique and Court premieres are listed separately for each work (albeit information is sometimes incomplete). The left-hand column includes both absolute world premieres and important earlier works new to these theatres. Works given across a New Year period are listed twice. Individual entrées are mentioned only when revived separately, or to avoid ambiguity. Prologues are mostly ignored. Sources: BrennerD, KaehlerO, LagraveTP, LajarteO, Lavallière, Mercure, NG, RiceFB, SerreARM. Italian works follow name forms etc. cited in Parisian libretti. LEGEND: ARM = Académie Royale de Musique (Paris Opéra); bal. = ballet; bouf. = bouffon; CI = Comédie-Italienne; cmda = comédie mêlée d’ariettes; com. lyr. = comédie lyrique; d. gioc.= dramma giocoso; div. scen. = divertimento scenico; FB = Fontainebleau; FSG = Foire Saint-Germain; FSL = Foire Saint-Laurent; hér. = héroïque; int. = intermezzo; NG = The New Grove Dictionary of Music; NGO = The New Grove Dictionary of Opera; op. = opéra; p. = pastorale; Vers. = Versailles; < = extract from; R = revised. 1753 ALL AT ARM EXCEPT WHERE MARKED Premieres at ARM (listed first) and Court Revivals at ARM or Court (by original date) Titon & l’Aurore (p. hér., 3: La Marre, Voisenon, Atys (Lully, 1676) FB La Motte / Mondonville, Jan. 9) Phaëton (Lully, 1683) Scaltra governatrice, La (d. gioc., 3: Palomba / Fêtes Grecques et romaines, Les (Blamont, 1723) Cocchi, Jan. 25) Danse, La (<Fêtes d’Hébé, Les)(Rameau, 1739) FB Jaloux corrigé, Le (op. -

Rousseau and the Social Contract

In Dialogue with Humanity Rousseau and The Social Contract by Leung Mei Yee Ho Wai Ming Yeung Yang Part I Rousseau‟s life and works Part II The Discourses – Critique of society and civilization Part III The Social Contract Part 1 Rousseau‟s life and works… and the people who influenced him 3 Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) One of the most influential yet controversial figures of the Enlightenment 4 He was the most portrayed character of the 18th century apart from Napoleon. (Jean-Jacques Monney) 5 Best known to the world by his political theory, he was also a well admired composer, and author of important works in very different fields. 6 Major works Novels Julie: or the New Héloïse (1761) Emile: or, on Education (1762) Autobiographical works The Reveries of the Solitary Walker (1782) The Confessions (1782-89) Essays Discourse on the Sciences and Arts (1750) Discourse on Inequality (1755) Discourse on Political Economy (1755-56) The Social Contract (1762) 7 Major Works Letters Letters on French Music (1753) Letters on the Elements of Botany (1780) Letter to M. d’Alembert on the Theatre (1758) Letters written from the Mountain (1764) Music Opera: Le devin du village (1752) Dictionary of Music (1767) 8 Born in 1712 in Geneva Small Calvinist city-state surrounded by large, predominately Catholic nations; Republic in the midst of duchies and monarchies Was brought up by his father The house where Rousseau since his mother died in was born at number 40, place du Bourg-de-Four childbirth 9 Left Geneva at the -

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-2012)

É T U D E 5 5 U R L E 1 8' 5 1 È ( L E X V 1 1 1 Revue fondée par Ro land Mortier et Hervé Hasquin DIRECTEURS Valérie André et Brigitte D'Hainaut-Zveny COMITt tDITORIAL Bruno Bernard, Claude Bruneel (Université catholique de Louvain), Carlo Capra (Università degli studi, Milan), David Charlton (Roya l Holloway College, Londres), Manuel Couvreur, Nicolas Cronk (Vo ltaire Foundation, University of Oxford), Michèle Galand, Jan Herman (Katholi eke Universiteit Leuven), Michel Jangoux, Huguette Krief (Un iversité de Provence, Aix-en-Provence), Christophe Loir, Roland Mortier, Fabrice Preyat, Dan iel Rabreau (U niverSité de Paris l, Panthéon-Sorbonne), Daniel Roche (Collège de France), Raymond Trousson et Renate Zedinger (Universitat Wien) GROUPE D'ÉTUDE D U 1 8' 5 1 È ( L E tCRIREÀ Valérie André [email protected] Brigitte D'Hainaut-Zveny Brigitte.D Hainaut @ulb.ac.be ou à l'adresse suivante Groupe d'étude du XVIII' siècle Université libre de Bruxelles (CP 175/01) Avenue F.D. Roosevelt 50 • B -1050 Bruxelles JEAN-JACQUES ROUSSEAU (1712-2012) MATÉRIAUX POUR UN RENOUVEAU CRITIQUE Publié avec l'aide financière du Fonds de la recherche scientifique - FNRS Ë T U DES 5 URL E 1 8' 5 1 È ( L E x v 1 1 1 JEAN-JACQUES ROUSSEAU (1712-2012) MATÉRIAUX POUR UN RENOUVEAU CRITIQUE VOLUME COMPOSÉ ET ÉDITÉ PAR CHRISTOPHE VAN STAEN 2 0 1 2 ÉDITIONS DE L'UNIVERSITÉ DE BRUXELLES DAN 5 L A M Ê M E COLLECTION Les préoccupations économiques et sociales des philosophes, littérateurs et artistes au XVIII e siècle, 1976 Bruxelles au XVIIIe siècle, 1977 L'Europe et les révolutions (1770-1800), 1980 La noblesse belge au XVIIIe siècle, 1982 Idéologies de la noblesse, 1984 Une famille noble de hauts fonctionnaires: les Neny, 1985 Le livre à Liège et à Bruxelles au XVIIIe siècle, 1987 Unité et diversité de l'empire des Habsbourg à la fin du XVIIIe siècle, 1988 Deux aspects contestés de la politique révolutionnaire en Belgique: langue et culte, 1989 Fêtes et musiques révolutionnaires: Grétry et Gossec, 1990 Rocaille. -

Phl 656: the Subject of Politics—Jean Jacques Rousseau Winter and Spring Quarters, 2015 Peg Birmingham

PHL 656: THE SUBJECT OF POLITICS—JEAN JACQUES ROUSSEAU WINTER AND SPRING QUARTERS, 2015 PEG BIRMINGHAM Office: Clifton, Suite 150.20 Telephone: 325-7266 Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Fridays, 1:30-2:30 and by appointment “Rousseau…was perhaps the first thinker of community, or more exactly, the first to experience the question of society as an uneasiness directed toward the community, and as the consciousness of a (perhaps irreparable) rupture in this community.” (Jean-Luc Nancy, The Inoperable Community) COURSE OBJECTIVES This course (which continues through spring quarter) will examine several works of Jean- Jacques Rousseau’s, including Discourse on the Arts and Sciences, Discourse on the Origin of Inequality, On the Origin of Languages, Emile, and The Social Contract, in an attempt to grasp Rousseau’s understanding of the subject of politics in the double sense of the nature of the political and the nature of political subjectivity. Of particular concern will be Rousseau’s account of the move from the amour de soi to the amour proper wherein the complex relations between nature and culture, the individual and the political, reason and desire, and morality and freedom come into play. Understanding this movement of desire is central to understanding Rousseau’s political project insofar as he claims that the perversion of the amour-propre underlies all political and social disorder, leading to the corruption and violence of both the individual and society. In other words, it is the perversion of the play of recognition and desire that gives way to the most horrible states of violence. -

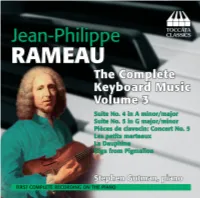

Toccata Classics TOCC0052 Notes

RAMEAU ON THE PIANO, VOLUME THREE 1 by Graham Sadler The two suites recorded on this disc are from the Nouvelles suites de pièces de clavecin of 1729 or 1730, Rameau’s final collection of solo keyboard music.2 Like those of his Pièces de clavessin (1724), they are contrasted both in tonality and character. The Suite in A minor and major is dominated by dances and includes only three character pieces, whereas the Suite in G major and minor consists almost exclusively of pieces with character titles. In its make-up if not its style, the latter thus follows the example of François Couperin, whose first three books of pièces de clavecin (1713, 1717 and 1722) had established the vogue for descriptive pieces. In that sense, Rameau may be regarded as somewhat conservative in devoting half of his two mature solo collections to suites of the more traditional type. Suite No. 4 in A minor and major Conservative they may be, but the dance movements of the Nouvelles suites are among the most highly P developed in the repertory, the first two particularly so. The Allemande 1 unfolds with an effortless grace, its unerring sense of direction reinforced by the many sequential passages. At the end of both sections, the duple semiquaver motion gives way unexpectedly to triplet motion, providing a memorable ‘rhyme’ to the two parts of the movement. The Courante 2, more than twice as long as its predecessors in Rameau’s output, displays a technical sophistication without parallel in the clavecin repertory. Three themes interlock in mainly three- part counterpoint – a bold motif in rising fourths, and two accompanying figures in continuous quavers, the one in sinuous stepwise movement, the other comprising cascading arpeggios. -

Performance in and of the Essay Film: Jean-Luc Godard Plays Jean-Luc Godard in Notre Musique (2004) Laura Rascaroli University College Cork

SFC_9.1_05_art_Rascaroli.qxd 3/6/09 8:49 AM Page 49 Studies in French Cinema Volume 9 Number 1 © 2009 Intellect Ltd Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/sfc.9.1.49/1 Performance in and of the Essay film: Jean-Luc Godard plays Jean-Luc Godard in Notre musique (2004) Laura Rascaroli University College Cork Abstract Keywords The ‘essay film’ is an experimental, hybrid, self-reflexive form, which crosses Essay film generic boundaries and systematically employs the enunciator’s direct address to Jean-Luc Godard the audience. Open and unstable by nature, it articulates its rhetorical concerns in performance a performative manner, by integrating into the text the process of its own coming communicative into being, and by allowing answers to emerge in the position of the embodied negotiation spectator. My argument is that performance holds a privileged role in Jean-Luc authorial self- Godard’s essayistic cinema, and that it is, along with montage, the most evident representation site of the negotiation between film-maker and film, audience and film, film and Notre musique meaning. A fascinating case study is provided by Notre musique/Our Music (2004), in which Godard plays himself. Communicative negotiation is, I argue, both Notre musique’s subject matter and its textual strategy. It is through the variation in registers of acting performances that the film’s ethos of unreserved openness and instability is fully realised, and comes to fruition for its embodied spectator. In a rare scholarly contribution on acting performances in documentary cinema, Thomas Waugh reminds us that the classical documentary tradition took the notion of performance for granted; indeed, ‘semi-fictive characteri- zation, or “personalization,”… seemed to be the means for the documentary to attain maturity and mass audiences’ (Waugh 1990: 67). -

Cpo 555 156 2 Booklet.Indd 1 12.06.2020 09:36:39 Jean-Philippe Rameau

Jean-Philippe Rameau Pigmalion · Dardanus Suites & Arias Anders J. Dahlin L’Orfeo Barockorchester Michi Gaigg cpo 555 156_2 Booklet.indd 1 12.06.2020 09:36:39 Jean-Philippe Rameau cpo 555 156_2 Booklet.indd 2 12.06.2020 09:36:39 Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683–1764) Pigmalion Acte-de-ballet, 1748 Livret by Sylvain Ballot de Sauvot (1703–60), after ‘La Sculpture’ from Le Triomphe des arts (1700) by Houdar de la Motte (1672–1731) (selected movements: Suite & Arias) 1 Ouverture 4'41 2 [Air,] ‘Fatal Amour’ (Pigmalion) 3'22 3 Air. Très lent – Gavotte gracieuse – Menuet – Gavotte gai – Chaconne vive – 5'44 Loure – Passepied vif – Rigaudon vif – Sarabande pour la Statue – Tambourin 4 Air gai 2'19 5 Pantomime niaise 0'44 6 2e Pantomime très vive 2'07 7 Ariette, ‘Règne Amour’ (Pigmalion) 4'35 8 Air pour les Graces, Jeux et Ris 0'50 9 Rondeau Contredanse 1'37 cpo 555 156_2 Booklet.indd 3 12.06.2020 09:36:39 Dardanus Tragedie en musique, 1739 (rev. 1744, 1760) Livret by Charles-Antoine Leclerc de La Bruère (1716–54) (selected movements: Suite & Arias) 10 Ouverture 4'13 11 Prologue, sc. 1: Air pour les [Jeux et les] Plaisirs [et la Jalousie et sa Suite] 1'06 12 Air pour les [Jeux et les] Plaisirs 1'05 13 Prologue, sc. 2: Air gracieux [pour les Peuples de différentes nations] 1'30 14 Rigaudon 1'41 15 Act 1, sc. 3: Air vif 2'46 16 Rigaudons 1 et 2 3'36 17 Act 2, sc. 1: Ritournelle vive 1'08 18 Act 4, sc. -

By Virgil W Topazio

VOLTAIRE AND ROUSSEAU: HUMANISTS AND HUMANITARIANS IN CONFLICT by Virgil W Topazio Whether judged as men, philosophers, or writers, it would be difficult to imagine two persons more different than Voltaire and Rousseau, yet they were both literary giants of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment who believed they had devoted most of their adult lives to the cause of political and moral freedom and justice. Voltaire was the beneficiary of a formal classical education that served as a solid base to his broad cultural background and wide reading. He un- abashedly enjoyed the flourishing eighteenth-century salon life with its pre- mium on wit, conversational skills, and intellect. And despite his capacities for strong emotions, his manner of coping with the overriding problen~of injustice was through the exercise of reason and intellect. Theodore Bester- man informs us in his recent biography of Voltaire: "The truth is that this nlost profound conviction (i.e., love of justice) was the fruit of Voltaire's reason, but it was expressed with all the deepest passions of his being.. Indeed, Voltaire was utterly a man of the mind."' Rousseau, on the other hand, possessed neither the classical education nor the broad systematic learning of Voltaire, though he was an unusually well- read autodidact in the eyes of Marguerite Reichenburg.' What is more important, Rousseau was by nature much more introverted than his extra- verted contenlporary, lacked Voltaire's conversational skills and sharp wit, and what is more, notwithstanding his protestations, was almost totally devoid of a sense of humor. He himself would probably have admitted that in his youth he had sold his soul to a Mephistophelian Paris. -

History of Structuralism. Vol. 2

DJFHKJSD History of Structuralism Volume 2 This page intentionally left blank History of Structuralism Volume 2: The Sign Sets, 1967-Present Francois Dosse Translated by Deborah Glassman University of Minnesota Press Minneapolis London The University of Minnesota Press gratefully acknowledges financial assistance provided by the French Ministry of Culture for the translation of this book. Copyright 1997 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota Originally published as Histoire du structuralisme, 11. Le chant du cygne, de 1967 anos jour«; Copyright Editions La Decouverte, Paris, 1992. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by the University of Minnesota Press III Third Avenue South, Suite 290, Minneapolis, MN 554°1-2520 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper http://www.upress.umn.edu First paperback edition, 1998 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dosse, Francois, 1950- [Histoire du structuralisme. English] History of structuralism I Francois Dosse ; translated by Deborah Glassman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. Contents: v. 1. The rising sign, 1945-1966-v. 2. The sign sets, 1967-present. ISBN 0-8166-2239-6 (v. I: he: alk. paper}.-ISBN 0-8166-2241-8 (v. I: pbk. : alk. paper}.-ISBN 0-8166-2370-8 (v. 2: hc: alk. paper}.-ISBN 0-8166-2371-6 (v. 2: pbk. : alk. paper}.-ISBN 0-8166-2240-X (set: hc: alk. paper}.-ISBN 0-8166-2254-X (set: pbk. -

Promenade En Suisse Romande POUR UN QUESTIONNEMENT DES LIENS ENTRE LANGUE, TERRITOIRE ET IDENTITÉ(S) ______

Promenade en Suisse romande POUR UN QUESTIONNEMENT DES LIENS ENTRE LANGUE, TERRITOIRE ET IDENTITÉ(S) ________ Hélène BARTHELMEBS-RAGUIN (Université du Luxembourg, RU IPSE) Pour citer cet article : Hélène BARTHELMEBS-RAGUIN, « Promenade en Suisse romande – Pour un questionnement des liens entre langue, territoire et identité(s) », Revue Proteus, no 15, (dés)identification postcoloniale de l’art contemporain, Phoebe Clarke et Bruno Trentini (coord.), 2019, p. 53-64. Résumé Longtemps les productions artistiques helvétiques ont été enfermées dans un rapport attrac- tion / répulsion vis-à-vis du voisin français. Pourtant, si les artistes suisses sont proches géographique- ment de la France, usent de la même langue et partagent des références communes, l’effet de frontière est ici tout à fait opérant et ses manifestations se retrouvent au niveau littéraire. La proximité entre ces deux aires culturelles amène les auteur·rice·s à interroger leur place sur la scène des littératures de langue française. Comment, dès lors, envisager ces écritures décentrées ? littérature romande — centre/périphérie — assimilation/marginalisation — langue Abstract For a long time, Swiss artistic productions have been locked in an attraction / repulsion relation with the French neigh- bor. The Swiss artists are geographically close to France, they use the same language, and they share common references, however the border effects are here quite operative and their manifestations impact the literary level. The proximity bet- ween these cultural areas leads the authors -

THE POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY of JEAN-JACQUES ROUSSEAU the Impossibilityof Reason

qvortrup.cov 2/9/03 12:29 pm Page 1 Was Rousseau – the great theorist of the French Revolution – really a Conservative? THE POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY OF JEAN-JACQUES ROUSSEAU This original study argues that the author of The Social Contract was a constitutionalist much closer to Madison, Montesquieu and Locke than to revolutionaries. Outlining his profound opposition to Godless materialism and revolutionary change, this book finds parallels between Rousseau and Burke, as well as showing that Rousseau developed the first modern theory of nationalism. The book presents an inte- grated political analysis of Rousseau’s educational, ethical, religious and political writings. The book will be essential readings for students of politics, philosophy and the history of ideas. ‘No society can survive without mutuality. Dr Qvortrup’s book shows that rights and responsibilities go hand in hand. It is an excellent primer for any- one wishing to understand how renewal of democracy hinges on a strong civil society’ The Rt. Hon. David Blunkett, MP ‘Rousseau has often been singled out as a precursor of totalitarian thought. Dr Qvortrup argues persuasively that Rousseau was nothing of the sort. Through an array of chapters the book gives an insightful account of Rousseau’s contribution to modern philosophy, and how he inspired individuals as diverse as Mozart, Tolstoi, Goethe, and Kant’ John Grey, Professor of European Political Thought,LSE ‘Qvortrup has written a highly readable and original book on Rousseau. He approaches the subject of Rousseau’s social and political philosophy with an attractively broad vision of Rousseau’s thought in the context of the development of modernity, including our contemporary concerns.