A Survey on Trumpet Articulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EW Hollywood Orchestra Opus Edition User Manual

USER MANUAL 1.0.6 < CONTENTS HOLLYWOOD ORCHESTRA OPUS EDITION INFORMATION The information in this document is subject to change without notice and does not represent a commitment on the part of East West Sounds, Inc. The software and sounds described in this document are subject to License Agreements and may not be copied to other media. No part of this publication may be copied, reproduced or otherwise transmitted or recorded, for any purpose, without prior written permission by East West Sounds, Inc. All product and company names are ™ or ® trademarks of their respective owners. Solid State Logic (SSL) Channel Strip, Transient Shaper, and Stereo Compressor licensed from Solid State Logic. SSL and Solid State Logic are registered trademarks of Red Lion 49 Ltd. © East West Sounds, Inc., 2021. All rights reserved. East West Sounds, Inc. 6000 Sunset Blvd. Hollywood, CA 90028 USA 1-323-957-6969 voice 1-323-957-6966 fax For questions about licensing of products: [email protected] For more general information about products: [email protected] For technical support for products: http://www.soundsonline.com/Support < CONTENTS HOLLYWOOD ORCHESTRA OPUS EDITION CREDITS PRODUCERS Doug Rogers, Nick Phoenix, Thomas Bergersen SOUND ENGINEER Shawn Murphy ENGINEERING ASSISTANCE Jeremy Miller, Ken Sluiter, Bo Bodnar PRODUCTION COORDINATORS Doug Rogers, Blake Rogers, Rhys Moody PROGRAMMING / SOUND DESIGN Justin Harris, Jason Coffman, Doug Rogers, Nick Phoenix SCRIPTING Wolfgang Schneider, Thomas Bergersen, Klaus Voltmer, Patrick Stinson -

Beethoven Op. 131 Manuscript Markings NK 20170701.Pages

A paper by Nicholas Kitchen about manuscript markings in Beethoven in general and in particular about their use in Op. 131, expanded from a paper presented for the Boston University Beethoven Institute in April 2017 I am honored to share with you today some of the exciting surprises that have come from rehearsing and performing directly from pdf files of Beethoven's manuscripts. The Beethoven editions I first encountered (at least for quartets) were the Joachim- Moser editions, which I now see as lovingly mauled editorial efforts. Regardless of any editions, I heard beautiful performances of Beethoven's music, treasures in my memory that continually inspire my current endeavors to try to bring the beauty of his compositions to life. But the particular beauty of Beethoven quickly demands from us the realization that the details of our interface with the markings in his music DO matter a great deal, and that they mattered a great deal to Beethoven himself. Studying at Curtis, I witnessed the transition to Henle Urtext as the trusted source of learning about Beethoven. My single most inspiring class was one led by my teacher Szymon Goldberg, where all of his students had our Henle piano scores of all ten Beethoven Sonatas (we also consulted Joachim's solutions to certain issues) and all together we went through all ten sonatas multiple times, with all of us taking turns performing different Sonatas. Mr. Goldberg made vivid to us the concept that !1 of 92! Beethoven's markings were living instructions from one virtuoso performer to another, and he had a nice saying: "The composer wants the performance to succeed even MORE than you do". -

Articulation from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Articulation From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Examples of Articulations: staccato, staccatissimo,martellato, marcato, tenuto. In music, articulation refers to the musical performance technique that affects the transition or continuity on a single note, or between multiple notes or sounds. Types of articulations There are many types of articulation, each with a different effect on how the note is played. In music notation articulation marks include the slur, phrase mark, staccato, staccatissimo, accent, sforzando, rinforzando, and legato. A different symbol, placed above or below the note (depending on its position on the staff), represents each articulation. Tenuto Hold the note in question its full length (or longer, with slight rubato), or play the note slightly louder. Marcato Indicates a short note, long chord, or medium passage to be played louder or more forcefully than surrounding music. Staccato Signifies a note of shortened duration Legato Indicates musical notes are to be played or sung smoothly and connected. Martelato Hammered or strongly marked Compound articulations[edit] Occasionally, articulations can be combined to create stylistically or technically correct sounds. For example, when staccato marks are combined with a slur, the result is portato, also known as articulated legato. Tenuto markings under a slur are called (for bowed strings) hook bows. This name is also less commonly applied to staccato or martellato (martelé) markings. Apagados (from the Spanish verb apagar, "to mute") refers to notes that are played dampened or "muted," without sustain. The term is written above or below the notes with a dotted or dashed line drawn to the end of the group of notes that are to be played dampened. -

Composers' Bridge!

Composers’ Bridge Workbook Contents Notation Orchestration Graphic notation 4 Orchestral families 43 My graphic notation 8 Winds 45 Clefs 9 Brass 50 Percussion 53 Note lengths Strings 54 Musical equations 10 String instrument special techniques 59 Rhythm Voice: text setting 61 My rhythm 12 Voice: timbre 67 Rhythmic dictation 13 Tips for writing for voice 68 Record a rhythm and notate it 15 Ideas for instruments 70 Rhythm salad 16 Discovering instruments Rhythm fun 17 from around the world 71 Pitch Articulation and dynamics Pitch-shape game 19 Articulation 72 Name the pitches – part one 20 Dynamics 73 Name the pitches – part two 21 Score reading Accidentals Muddling through your music 74 Piano key activity 22 Accidental practice 24 Making scores and parts Enharmonics 25 The score 78 Parts 78 Intervals Common notational errors Fantasy intervals 26 and how to catch them 79 Natural half steps 27 Program notes 80 Interval number 28 Score template 82 Interval quality 29 Interval quality identification 30 Form Interval quality practice 32 Form analysis 84 Melody Rehearsal and concert My melody 33 Presenting your music in front Emotion melodies 34 of an audience 85 Listening to melodies 36 Working with performers 87 Variation and development Using the computer Things you can do with a Computer notation: Noteflight 89 musical idea 37 Sound exploration Harmony My favorite sounds 92 Harmony basics 39 Music in words and sentences 93 Ear fantasy 40 Word painting 95 Found sound improvisation 96 Counterpoint Found sound composition 97 This way and that 41 Listening journal 98 Chord game 42 Glossary 99 Welcome Dear Student and family Welcome to the Composers' Bridge! The fact that you are being given this book means that we already value you as a composer and a creative artist-in-training. -

Ames High School Music Department Orchestra Course Level Expectations Grades 10-12 OR.PP Position/Posture OR.PP.1 Understands An

Ames High School Music Department Orchestra Course Level Expectations Grades 10-12 OR.PP Position/Posture OR.PP.1 Understands and demonstrates appropriate playing posture without prompts OR.PP.2 Understands and demonstrates correct finger/hand position without prompts OR.AR Articulation OR.AR.1 Interprets and performs combinations of bowing at an advanced level [tie, slur, staccato, hooked bowings, loure (portato) bowing, accent, spiccato, syncopation, and legato] OR.AR.2 Interprets and performs Ricochet, Sul Ponticello, and Sul Tasto bowings at a beginning level OR.TQ Tone Quality OR.TQ.1 Produces a characteristic tone at the medium-advanced level OR.TQ.2 Defines and performs proper ensemble balance and blend at the medium-advanced level OR.RT Rhythm/Tempo OR.RT.1 Defines and performs rhythm patterns at the medium-advanced level (quarter note/rest, half note/rest, eighth note/rest, dotted eighth note, dotted half note, whole note/rest, dotted quarter note, sixteenth note) OR.RT.2 Defines and performs tempo markings at a medium-advanced level (Allegro, Moderato, Andante, Ritardando, Lento, Andantino, Maestoso, Andante Espressivo, Marziale, Rallantando, and Presto) OR.TE Technique OR.TE.1 Performs the pitches and the two-octave major scales for C, G, D, A, F, Bb, Eb; performs the pitches and the two-octave minor scales for A, E, D, G, C; performs the pitches and the one-octave chromatic scale OR.TE.2 Demonstrates and performs pizzicato, acro, and left-hand pizzicato at the medium-advanced level OR.TE.3 Demonstrates shifting at the intermediate -

Ornamentos-Musicais.Pdf

JEAN RICARDO MARQUES ORNAMENTOS Musicais SALVADOR 2014 1 SUMÁRIO 1. INTRODUÇÃO ...............................................................................................3 2. TIPOS DE ORNAMENTOS NA MÚSICA ERUDITA ......................................3 3. TIPOS DE ORNAMENTOS NA MÚSICA POPULAR ....................................8 4. CONSIDERAÇÕES FINAIS ..........................................................................12 REFERÊNCIAS BIBLIOGRÁFICAS ................................................................ 13 2 1. INTRODUÇÃO Este estudo trata dos ornamentos na música erudita, também chamados de “efeitos” na música popular. Em música, são chamados ornamentos os embelezamentos e decorações de uma melodia, expressos através de pequenas notas ou sinais especiais. A ornamentação fazia muito sentido nos séculos XIV até XVI devido ao amplo uso do Cravo. Este instrumento por sua vez, não segurava uma nota por tanto tempo quanto o Piano, deixando assim lacunas entre uma nota e outra ou o término de um tema e o início de um desenvolvimento/cadência. Desta forma os ornamentos tornaram-se amplamente utilizados neste período. Na musica Erudita, os ornamentos possuem características próprias sobre as notas que englobam e as notas que acrescentam. São eles o: Trinado (ou Trilo), Mordente, Grupetto (ou Gruppeto, Gruppetto, Grupeto), Appoggiatura (ou Apogiatura, Apojatura), Floreio, Portamento, Cadência (ou Cadenza), Arpeggio (ou Arpejo, Harpejo) e Glissando. Ornamentos na música popular consistem em extrair sonoridades e interpretações diferentes que incidem sobre determinado trecho musical, mediante a utilização de diversos sistemas de execução. Esses efeitos tem origem na guitarra elétrica e foram adaptados e usados nos baixos elétrico e são, em parte, aquilo que define a peculiaridade do músico. 2. TIPOS DE ORNAMENTOS NA MÚSICA ERUDITA Segue abaixo os ornamentos mais usados na música erudita: a) Trinado Esta representado por um tr colocado sempre acima da nota independente se ela tem a haste virada para cima ou para baixo. -

Slap Tongue (Saxophone Pizzicato)

Excerpt from “Part IV: Extended Techniques for Saxophone” Writing for Saxophones: A Guide to the Tonal Palette of the Saxophone Family for Composers, Arrangers and Performers by Jay C. Easton, D.M.A. (for further excerpts and ordering information, please visit http://baxtermusicpublishing.com) • Slap Tongue (saxophone pizzicato) Slap tongue is a versatile and interesting effect that is available in four varieties: 1. “melodic” slap or pizzicato (clearly pitched): melodic “plucking” sound entire keyed range of horn (but not altissimo) Maximum tempo: 240 beats per minute Possible from p to f dynamics 2. “slap tone” (clearly pitched): melodic slap attack followed by normal tone Maximum tempo: 200 beats per minute Possible from p to f dynamics 3. “woodblock” slap (unpitched): soft, dry percussive sound Maximum tempo: 200 beats per minute Possible from p to mf dynamics 4. “explosive” slap or “open” slap (unpitched): loud percussive sound Maximum tempo: 70 beats per minute Possible from mf to ff dynamics Not all saxophonists know how to slap tongue but an increasing number are learning the technique. The “melodic” slap and “slap tone” are produced by holding the tongue against about 1/3 to 1/2 of the tip end of the reed surface – a centimeter or so – and creating a suction-cup effect between tongue and reed. This is accomplished by pulling the middle of the tongue slightly away from the reed while keeping the edges and tip of the tongue sealed tight against it. The tongue is then quickly released by pushing it forward and downward away from the reed, creating suction between the tongue and the reed; this tongue motion is accompanied by sudden slight impulse of air. -

Musixtex Using TEX to Write Polyphonic Or Instrumental Music Version T.111 – April 1, 2003

c MusiXTEX Using TEX to write polyphonic or instrumental music Version T.111 – April 1, 2003 Daniel Taupin Laboratoire de Physique des Solides (associ´eau CNRS) bˆatiment 510, Centre Universitaire, F-91405 ORSAY Cedex E-mail : [email protected] Ross Mitchell CSIRO Division of Atmospheric Research, Private Bag No.1, Mordialloc, Victoria 3195, Australia Andreas Egler‡ (Ruhr–Uni–Bochum) Ursulastr. 32 D-44793 Bochum ‡ For personal reasons, Andreas Egler decided to retire from authorship of this work. Never- therless, he has done an important work about that, and I decided to keep his name on this first page. D. Taupin Although one of the authors contested that point once the common work had begun, MusiXTEX may be freely copied, duplicated and used in conformance to the GNU General Public License (Version 2, 1991, see included file copying)1 . You may take it or parts of it to include in other packages, but no packages called MusiXTEX without specific suffix may be distributed under the name MusiXTEX if different from the original distribution (except obvious bug corrections). Adaptations for specific implementations (e.g. fonts) should be provided as separate additional TeX or LaTeX files which override original definition. 1Thanks to Free Software Foundation for advising us. See http://www.gnu.org Contents 1 What is MusiXTEX ? 6 1.1 MusiXTEX principal features . 7 1.1.1 Music typesetting is two-dimensional . 7 1.1.2 The spacing of the notes . 8 1.1.3 Music tokens, rather than a ready-made generator . 9 1.1.4 Beams . 9 1.1.5 Setting anything on the score . -

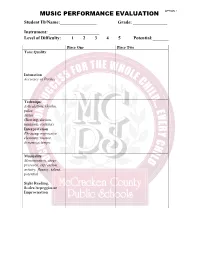

Music Performance Evaluation

OPTION 1 Student ID/Name:________________ Grade: _______________ Instrument: ______________________ Level of Difficulty: 1 2 3 4 5 Potential:_______ Piece One Piece Two Tone Quality Intonation Accuracy of Pitches Technique Articulation, rhythm, pulse, Meter (Bowing, diction, tonguing, sticking) Interpretation Phrasing, expressive elements, nuance, dynamics, tempo Musicality Memorization, stage presence, expression, artistry, fluency, talent, potential Sight Reading, Scales/Arpeggios or Improvisation OPTION 1 Distinguished Proficient Apprentice Novice Tone Quality Tone is warm, resonant, Tone has some Tone has apparent Tone is weak, controlled, clear, focused, warmth, resonance inconsistencies breathy, forced consistent, vibrant, rich, and clarity, with with some or unclear. full, beautiful. some resonance and inconsistencies. clarity. Intonation Printed pitches are Some inaccurate Several inaccurate Inaccurate Accuracy of performed with accuracy; pitches and some pitches and pitches; out of intonation is within the intonation problems. difficulty tune. Pitches appropriate range. Student playing/singing in shifts cleanly. tune consistently. Technique Student used appropriate Enough technical Some technical Flawed Articulation, technique, as printed or flaws to detract from flaws. Not technique. indicated stylistically for performance. Style stylistically Inaccurate rhythm, pulse, the selection. Attacks and somewhat appropriate. rhythms, time Meter releases are clear. Slurs appropriate. Some Printed signature not (Bowing, diction, are smooth and connected. inconsistencies in articulations not followed, tonguing, Pulse of the music is performance or followed accents sticking, steady. Indicated meter is printed articulations. accurately. overdone or not performed correctly. Some unsteadiness Unsteady pulse. apparent. Slurs fingering) Notes and rests are held for of pulse. Some Several rhythmic are unclear. the correct value. rhythmic errors. errors. Technique is not appropriate stylistically. -

The Influence of Tonguing on Tone Production With

5th Congress of Alps-Adria Acoustics Association 12-14 September 2012, Petrþane, Croatia __________________________________________________________________________________________ !"#$% #' !($!(#) "#)!(#!(# !*+(, '"(#!-"! ."#)% /+ ,!-((,-"#,!"#.+ 0 #. Alex Hofmann,*¹ Vasileios Chatziioannou,* Wilfried Kausel,* Werner Goebl,* Michael Weilguni,# Walter Smetana # *Institute of Music Acoustics, University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna, Austria #Institute of Sensor and Actuator Systems, Vienna University of Technology, Austria ¹[email protected] Abstract: Physical modelling based sound-synthesis requires physically meaningful parameters for controlling the model. Previous studies on modelling single-reed woodwind instruments have concentrated mostly on the influence of the pressure difference across the reed on the behavior of the reed oscillation. The interaction with the player's lips and the mouthpiece lay has also been taken into account. However, studies on the effect of the player's tongue are limited. Articulation on real saxophones is produced by tongue impulses to the reed. In portato playing the air pressure is held approximately constant by the player, while there are articular interactions of the tongue with the reed. In this study we aim to explain the influence of tonguing for tone production with single-reed woodwind instruments using experimental measurements in an attempt to model articulation in sound synthesis. During the experiments an alto-saxophone mouthpiece was attached to the saxophone neck and tones with different articulation were recorded. The mouthpiece pressure was measured using a microphone inserted into the mouthpiece and a strain gauge glued on a synthetic reed was used to track the reed bending. A damping effect of the tongue on the oscillating reed can be observed between two articulated tones and the release of the tongue affects the transient behavior of the instrument. -

Extended Techniques in Stanley Friedman's

EXTENDED TECHNIQUES IN STANLEY FRIEDMAN'S SOLUS FOR UNACCOMPANIED TRUMPET Scott Meredith, B.M., B.M.E., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2008 APPROVED: Keith Johnson, Major Professor Lenora McCroskey, Minor Professor John Holt, Committee Member Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Meredith, Scott. Extended Techniques in Stanley Friedman’s Solus for Unaccompanied Trumpet. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2008, 37 pp., 25 examples, 3 tables, bibliography, 23 titles. This document examines the technical execution of extended techniques incorporated in the musical structure of Solus, and explores the benefits of introducing the work into the curriculum of a college level trumpet studio. Compositional style, form, technical accessibility, and pedagogical benefits are investigated in each of the four movements. An interview with the composer forms the foundation for the history of the composition as well as the genesis of some of the extended techniques and programmatic ideas. Copyright 2008 by Scott Meredith ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My deepest thanks go to Keith Johnson for his mentorship, guidance, and friendship. He has been instrumental in my development as a player, teacher, and citizen. I owe a great amount of gratitude to my colleagues John Wacker and Robert Murray for their continued support, encouragement, friendship, and belief in my dream. I owe a debt of gratitude to Lenora McCroskey for her knowledge of all things music and her willingness to drop everything for her students. -

Paired Syllables and Unequal Tonguing Patterns on Woodwinds in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries Bruce Haynes

Performance Practice Review Volume 10 Article 5 Number 1 Spring Tu ru or not Tu ru: Paired Syllables and Unequal Tonguing Patterns on Woodwinds in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries Bruce Haynes Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Haynes, Bruce (1997) "Tu ru or not Tu ru: Paired Syllables and Unequal Tonguing Patterns on Woodwinds in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 10: No. 1, Article 5. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199710.01.05 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol10/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 42 Bruce Haynes -> - As Hotteterre wrote, On observera seulement de ne point You must only observe never t prononcer Ru sur l& Tremblements; ni pronounce Ru on a shake, nor on sur deux Notes de suite, parceque le Ru two successive Notes, because Ru doit toujours &re m216 alternativement ought always to be intermixt alter- avec le TU.~ natively with TU' The R works when preceded by T,however (as in t dah). Quantz writes: I1 faut s'appliquer 2 prononcer trh fortement & distinctement la lettre r. sharply and clearly. It produces Cela fait 2 l'oreille le meme effet que the same effect on the ear as the lors qu'on se sen de di, en jouant de single-tongue di, although it does la simple langue: quoic)ue il ne not seem so to the player.