Musixtex Using TEX to Write Polyphonic Or Instrumental Music Version T.111 – April 1, 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EW Hollywood Orchestra Opus Edition User Manual

USER MANUAL 1.0.6 < CONTENTS HOLLYWOOD ORCHESTRA OPUS EDITION INFORMATION The information in this document is subject to change without notice and does not represent a commitment on the part of East West Sounds, Inc. The software and sounds described in this document are subject to License Agreements and may not be copied to other media. No part of this publication may be copied, reproduced or otherwise transmitted or recorded, for any purpose, without prior written permission by East West Sounds, Inc. All product and company names are ™ or ® trademarks of their respective owners. Solid State Logic (SSL) Channel Strip, Transient Shaper, and Stereo Compressor licensed from Solid State Logic. SSL and Solid State Logic are registered trademarks of Red Lion 49 Ltd. © East West Sounds, Inc., 2021. All rights reserved. East West Sounds, Inc. 6000 Sunset Blvd. Hollywood, CA 90028 USA 1-323-957-6969 voice 1-323-957-6966 fax For questions about licensing of products: [email protected] For more general information about products: [email protected] For technical support for products: http://www.soundsonline.com/Support < CONTENTS HOLLYWOOD ORCHESTRA OPUS EDITION CREDITS PRODUCERS Doug Rogers, Nick Phoenix, Thomas Bergersen SOUND ENGINEER Shawn Murphy ENGINEERING ASSISTANCE Jeremy Miller, Ken Sluiter, Bo Bodnar PRODUCTION COORDINATORS Doug Rogers, Blake Rogers, Rhys Moody PROGRAMMING / SOUND DESIGN Justin Harris, Jason Coffman, Doug Rogers, Nick Phoenix SCRIPTING Wolfgang Schneider, Thomas Bergersen, Klaus Voltmer, Patrick Stinson -

Beethoven Op. 131 Manuscript Markings NK 20170701.Pages

A paper by Nicholas Kitchen about manuscript markings in Beethoven in general and in particular about their use in Op. 131, expanded from a paper presented for the Boston University Beethoven Institute in April 2017 I am honored to share with you today some of the exciting surprises that have come from rehearsing and performing directly from pdf files of Beethoven's manuscripts. The Beethoven editions I first encountered (at least for quartets) were the Joachim- Moser editions, which I now see as lovingly mauled editorial efforts. Regardless of any editions, I heard beautiful performances of Beethoven's music, treasures in my memory that continually inspire my current endeavors to try to bring the beauty of his compositions to life. But the particular beauty of Beethoven quickly demands from us the realization that the details of our interface with the markings in his music DO matter a great deal, and that they mattered a great deal to Beethoven himself. Studying at Curtis, I witnessed the transition to Henle Urtext as the trusted source of learning about Beethoven. My single most inspiring class was one led by my teacher Szymon Goldberg, where all of his students had our Henle piano scores of all ten Beethoven Sonatas (we also consulted Joachim's solutions to certain issues) and all together we went through all ten sonatas multiple times, with all of us taking turns performing different Sonatas. Mr. Goldberg made vivid to us the concept that !1 of 92! Beethoven's markings were living instructions from one virtuoso performer to another, and he had a nice saying: "The composer wants the performance to succeed even MORE than you do". -

Articulation from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Articulation From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Examples of Articulations: staccato, staccatissimo,martellato, marcato, tenuto. In music, articulation refers to the musical performance technique that affects the transition or continuity on a single note, or between multiple notes or sounds. Types of articulations There are many types of articulation, each with a different effect on how the note is played. In music notation articulation marks include the slur, phrase mark, staccato, staccatissimo, accent, sforzando, rinforzando, and legato. A different symbol, placed above or below the note (depending on its position on the staff), represents each articulation. Tenuto Hold the note in question its full length (or longer, with slight rubato), or play the note slightly louder. Marcato Indicates a short note, long chord, or medium passage to be played louder or more forcefully than surrounding music. Staccato Signifies a note of shortened duration Legato Indicates musical notes are to be played or sung smoothly and connected. Martelato Hammered or strongly marked Compound articulations[edit] Occasionally, articulations can be combined to create stylistically or technically correct sounds. For example, when staccato marks are combined with a slur, the result is portato, also known as articulated legato. Tenuto markings under a slur are called (for bowed strings) hook bows. This name is also less commonly applied to staccato or martellato (martelé) markings. Apagados (from the Spanish verb apagar, "to mute") refers to notes that are played dampened or "muted," without sustain. The term is written above or below the notes with a dotted or dashed line drawn to the end of the group of notes that are to be played dampened. -

Musical Notation Codes Index

Music Notation - www.music-notation.info - Copyright 1997-2019, Gerd Castan Musical notation codes Index xml ascii binary 1. MidiXML 1. PDF used as music notation 1. General information format 2. Apple GarageBand Format 2. MIDI (.band) 2. DARMS 3. QuickScore Elite file format 3. SMDL 3. GUIDO Music Notation (.qsd) Language 4. MPEG4-SMR 4. WAV audio file format (.wav) 4. abc 5. MNML - The Musical Notation 5. MP3 audio file format (.mp3) Markup Language 5. MusiXTeX, MusicTeX, MuTeX... 6. WMA audio file format (.wma) 6. MusicML 6. **kern (.krn) 7. MusicWrite file format (.mwk) 7. MHTML 7. **Hildegard 8. Overture file format (.ove) 8. MML: Music Markup Language 8. **koto 9. ScoreWriter file format (.scw) 9. Theta: Tonal Harmony 9. **bol Exploration and Tutorial Assistent 10. Copyist file format (.CP6 and 10. Musedata format (.md) .CP4) 10. ScoreML 11. LilyPond 11. Rich MIDI Tablature format - 11. JScoreML RMTF 12. Philip's Music Writer (PMW) 12. eXtensible Score Language 12. Creative Music File Format (XScore) 13. TexTab 13. Sibelius Plugin Interface 13. MusiXML: My own format 14. Mup music publication program 14. Finale Plugin Interface 14. MusicXML (.mxl, .xml) 15. NoteEdit 15. Internal format of Finale (.mus) 15. MusiqueXML 16. Liszt: The SharpEye OMR 16. XMF - eXtensible Music 16. GUIDO XML engine output file format Format 17. WEDELMUSIC 17. Drum Tab 17. NIFF 18. ChordML 18. Enigma Transportable Format 18. Internal format of Capella (ETF) (.cap) 19. ChordQL 19. CMN: Common Music 19. SASL: Simple Audio Score 20. NeumesXML Notation Language 21. MEI 20. OMNL: Open Music Notation 20. -

Ames High School Music Department Orchestra Course Level Expectations Grades 10-12 OR.PP Position/Posture OR.PP.1 Understands An

Ames High School Music Department Orchestra Course Level Expectations Grades 10-12 OR.PP Position/Posture OR.PP.1 Understands and demonstrates appropriate playing posture without prompts OR.PP.2 Understands and demonstrates correct finger/hand position without prompts OR.AR Articulation OR.AR.1 Interprets and performs combinations of bowing at an advanced level [tie, slur, staccato, hooked bowings, loure (portato) bowing, accent, spiccato, syncopation, and legato] OR.AR.2 Interprets and performs Ricochet, Sul Ponticello, and Sul Tasto bowings at a beginning level OR.TQ Tone Quality OR.TQ.1 Produces a characteristic tone at the medium-advanced level OR.TQ.2 Defines and performs proper ensemble balance and blend at the medium-advanced level OR.RT Rhythm/Tempo OR.RT.1 Defines and performs rhythm patterns at the medium-advanced level (quarter note/rest, half note/rest, eighth note/rest, dotted eighth note, dotted half note, whole note/rest, dotted quarter note, sixteenth note) OR.RT.2 Defines and performs tempo markings at a medium-advanced level (Allegro, Moderato, Andante, Ritardando, Lento, Andantino, Maestoso, Andante Espressivo, Marziale, Rallantando, and Presto) OR.TE Technique OR.TE.1 Performs the pitches and the two-octave major scales for C, G, D, A, F, Bb, Eb; performs the pitches and the two-octave minor scales for A, E, D, G, C; performs the pitches and the one-octave chromatic scale OR.TE.2 Demonstrates and performs pizzicato, acro, and left-hand pizzicato at the medium-advanced level OR.TE.3 Demonstrates shifting at the intermediate -

Ornamentos-Musicais.Pdf

JEAN RICARDO MARQUES ORNAMENTOS Musicais SALVADOR 2014 1 SUMÁRIO 1. INTRODUÇÃO ...............................................................................................3 2. TIPOS DE ORNAMENTOS NA MÚSICA ERUDITA ......................................3 3. TIPOS DE ORNAMENTOS NA MÚSICA POPULAR ....................................8 4. CONSIDERAÇÕES FINAIS ..........................................................................12 REFERÊNCIAS BIBLIOGRÁFICAS ................................................................ 13 2 1. INTRODUÇÃO Este estudo trata dos ornamentos na música erudita, também chamados de “efeitos” na música popular. Em música, são chamados ornamentos os embelezamentos e decorações de uma melodia, expressos através de pequenas notas ou sinais especiais. A ornamentação fazia muito sentido nos séculos XIV até XVI devido ao amplo uso do Cravo. Este instrumento por sua vez, não segurava uma nota por tanto tempo quanto o Piano, deixando assim lacunas entre uma nota e outra ou o término de um tema e o início de um desenvolvimento/cadência. Desta forma os ornamentos tornaram-se amplamente utilizados neste período. Na musica Erudita, os ornamentos possuem características próprias sobre as notas que englobam e as notas que acrescentam. São eles o: Trinado (ou Trilo), Mordente, Grupetto (ou Gruppeto, Gruppetto, Grupeto), Appoggiatura (ou Apogiatura, Apojatura), Floreio, Portamento, Cadência (ou Cadenza), Arpeggio (ou Arpejo, Harpejo) e Glissando. Ornamentos na música popular consistem em extrair sonoridades e interpretações diferentes que incidem sobre determinado trecho musical, mediante a utilização de diversos sistemas de execução. Esses efeitos tem origem na guitarra elétrica e foram adaptados e usados nos baixos elétrico e são, em parte, aquilo que define a peculiaridade do músico. 2. TIPOS DE ORNAMENTOS NA MÚSICA ERUDITA Segue abaixo os ornamentos mais usados na música erudita: a) Trinado Esta representado por um tr colocado sempre acima da nota independente se ela tem a haste virada para cima ou para baixo. -

Music Braille Code, 2015

MUSIC BRAILLE CODE, 2015 Developed Under the Sponsorship of the BRAILLE AUTHORITY OF NORTH AMERICA Published by The Braille Authority of North America ©2016 by the Braille Authority of North America All rights reserved. This material may be duplicated but not altered or sold. ISBN: 978-0-9859473-6-1 (Print) ISBN: 978-0-9859473-7-8 (Braille) Printed by the American Printing House for the Blind. Copies may be purchased from: American Printing House for the Blind 1839 Frankfort Avenue Louisville, Kentucky 40206-3148 502-895-2405 • 800-223-1839 www.aph.org [email protected] Catalog Number: 7-09651-01 The mission and purpose of The Braille Authority of North America are to assure literacy for tactile readers through the standardization of braille and/or tactile graphics. BANA promotes and facilitates the use, teaching, and production of braille. It publishes rules, interprets, and renders opinions pertaining to braille in all existing codes. It deals with codes now in existence or to be developed in the future, in collaboration with other countries using English braille. In exercising its function and authority, BANA considers the effects of its decisions on other existing braille codes and formats, the ease of production by various methods, and acceptability to readers. For more information and resources, visit www.brailleauthority.org. ii BANA Music Technical Committee, 2015 Lawrence R. Smith, Chairman Karin Auckenthaler Gilbert Busch Karen Gearreald Dan Geminder Beverly McKenney Harvey Miller Tom Ridgeway Other Contributors Christina Davidson, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Richard Taesch, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Roger Firman, International Consultant Ruth Rozen, BANA Board Liaison iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................. -

The Latex Graphics Companion / Michel Goossens

i i “tlgc2” — 2007/6/15 — 15:36 — page iii — #3 i i The LATEXGraphics Companion Second Edition Michel Goossens Frank Mittelbach Sebastian Rahtz Denis Roegel Herbert Voß Upper Saddle River, NJ • Boston • Indianapolis • San Francisco New York • Toronto • Montreal • London • Munich • Paris • Madrid Capetown • Sydney • Tokyo • Singapore • Mexico City i i i i i i “tlgc2” — 2007/6/15 — 15:36 — page iv — #4 i i Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and Addison-Wesley was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this book, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The publisher offers discounts on this book when ordered in quantity for bulk purchases and special sales. For more information, please contact: U.S. Corporate and Government Sales (800) 382-3419 [email protected] For sales outside of the United States, please contact: International Sales [email protected] Visit Addison-Wesley on the Web: www.awprofessional.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The LaTeX Graphics companion / Michel Goossens ... [et al.]. -- 2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-321-50892-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. -

Mutated! - Music Tagging Type Definition

University of Glasgow Funded by the Department of Music Joint Information Systems Committee Call: Communications and Information Technology Standards MuTaTeD! - Music Tagging Type Definition A project to provide a meta-standard for music mark-up by integrating two existing music standards (Report Jan 2000) Dr. Stephen Arnold Carola Boehm Dr. Cordelia Hall University of Glasgow Department of Music Department of Music MuTaTeD! Contents CONTENTS: I. INTRODUCTION (BY DR. STEPHEN ARNOLD).................................................................. 3 II. ACHIEVEMENTS AND DELIVERABLES (BY THE MUTATED! TEAM) .............................. 5 1. Conference Papers and Workshops ..................................................................................... 5 2. Contact with relevant research groups .................................................................................. 5 3. Future Dissemination Possibilities ......................................................................................... 6 III. SYSTEMS FOR MUSIC REPRESENTATION AND RETRIEVAL (BY CAROLA BOEHM) 8 1. Abstract .................................................................................................................................. 8 2. The Broad Context ................................................................................................................. 8 3. The Music-Specific Context ................................................................................................... 8 4. Music Representation Standards – The Historical -

Tablature for Lute, Cittern, and Bandora

1 ------------------------------------------------------------ Decoding Tablature Using Conversion Charts: ------------------------------------------------------------ Lute Tabs: Renaissance lute tabs came in a bewildering array, and practically each separate practitioner used a different system. They mostly amounted to three variants, all called "French" or "Italian". (The German system is really different, I won't go into it here, and the Spanish is really more of a precursor to the French and Italian.) Terminology Definitions as I use them: Tuning: The notes to which you tune the open strings of your lute. French open tuning=G −1 ,C 0 ,F 0 ,A 0 ,D 1 ,G 1 Italian open tuning=A −1 ,D 0 ,G 0 ,B 0 ,E 1 ,A 1 (Low to High strings.) Italian tuning would effectively just transpose the piece of music up one whole step. This matters when playing with others, otherwise, not so much. Instruments usually were tuned to themselves. Tab: High strings represented by top lines (French) or bottom lines (Italian) in tablature. Method: Numbers (Italian) or Letters (French). Any given writer could (and did) choose French or Italian for any of the three items above, declare that he was right, and the rest of the world was wrong, and prove it by using his variant. Thus, decisions of 2 possibilities for three items, 2 to the power three is eight possible charts. (See charts file. Eight charts for lute. I only did two for the cittern and one for bandora, but they, too, have 8 possible charts each.) An example of French tuning, tab, and method may be found in "Fond Wanton Youths", by Robert Jones, the "Nevv Booke of Tabliture," by William Barley, or Dowland's "First Book of Ayres." In the below charts: the top row is the letter on the staff lines in the tablature. -

Robotaba Guitar Tablature Transcription Framework

ROBOTABA GUITAR TABLATURE TRANSCRIPTION FRAMEWORK Gregory Burlet and Ichiro Fujinaga Centre for Interdisciplinary Research in Music Media and Technology McGill University, Montreal,´ Quebec,´ Canada [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper presents Robotaba, a web-based guitar tabla- ture transcription framework. The framework facilitates the creation of web applications in which polyphonic tran- scription and guitar tablature arrangement algorithms can be embedded. Such a web application is implemented, and Figure 1. Tablature notation depicting six different string consists of an existing polyphonic transcription algorithm and fret combinations to perform the note E4 on a 24-fret and a new guitar tablature arrangement algorithm. The re- guitar in standard tuning. sult is a unified system that is capable of transcribing gui- tar tablature from a digital audio recording and display- transcription process, the guitar can produce the same note ing the resulting tablature in the web browser. Addition- in several ways. For example, there exists six string and ally, two ground-truth datasets for polyphonic transcrip- fret combinations that can produce the note E4 on a 24-fret tion and guitar tablature arrangement are compiled from guitar in standard tuning (Figure 1). manual transcriptions gathered from the tablature website While several polyphonic transcription and guitar tab- ultimate-guitar.com. The implemented transcription lature arrangement algorithms have been proposed in the web application is evaluated on the compiled ground-truth literature, no frameworks have been developed to facilitate datasets using several metrics. the combination of these algorithms to produce an auto- matic guitar tablature transcription system. Moreover, af- 1. -

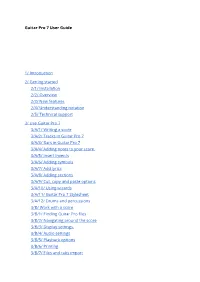

Guitar Pro 7 User Guide 1/ Introduction 2/ Getting Started

Guitar Pro 7 User Guide 1/ Introduction 2/ Getting started 2/1/ Installation 2/2/ Overview 2/3/ New features 2/4/ Understanding notation 2/5/ Technical support 3/ Use Guitar Pro 7 3/A/1/ Writing a score 3/A/2/ Tracks in Guitar Pro 7 3/A/3/ Bars in Guitar Pro 7 3/A/4/ Adding notes to your score. 3/A/5/ Insert invents 3/A/6/ Adding symbols 3/A/7/ Add lyrics 3/A/8/ Adding sections 3/A/9/ Cut, copy and paste options 3/A/10/ Using wizards 3/A/11/ Guitar Pro 7 Stylesheet 3/A/12/ Drums and percussions 3/B/ Work with a score 3/B/1/ Finding Guitar Pro files 3/B/2/ Navigating around the score 3/B/3/ Display settings. 3/B/4/ Audio settings 3/B/5/ Playback options 3/B/6/ Printing 3/B/7/ Files and tabs import 4/ Tools 4/1/ Chord diagrams 4/2/ Scales 4/3/ Virtual instruments 4/4/ Polyphonic tuner 4/5/ Metronome 4/6/ MIDI capture 4/7/ Line In 4/8 File protection 5/ mySongBook 1/ Introduction Welcome! You just purchased Guitar Pro 7, congratulations and welcome to the Guitar Pro family! Guitar Pro is back with its best version yet. Faster, stronger and modernised, Guitar Pro 7 offers you many new features. Whether you are a longtime Guitar Pro user or a new user you will find all the necessary information in this user guide to make the best out of Guitar Pro 7. 2/ Getting started 2/1/ Installation 2/1/1 MINIMUM SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS macOS X 10.10 / Windows 7 (32 or 64-Bit) Dual-core CPU with 4 GB RAM 2 GB of free HD space 960x720 display OS-compatible audio hardware DVD-ROM drive or internet connection required to download the software 2/1/2/ Installation on Windows Installation from the Guitar Pro website: You can easily download Guitar Pro 7 from our website via this link: https://www.guitar-pro.com/en/index.php?pg=download Once the trial version downloaded, upgrade it to the full version by entering your licence number into your activation window.